Forging ahead with a career in journalism is fraught with difficulty in the Philippines - and many are walking away. What went so wrong?

Days after the celebration of World Press Freedom last year in May, journalist Leonardo Corrales filed a complaint against Meta, the owners of Facebook, demanding that the social media giant disclose information about the anonymous accounts behind vicious online attacks he and his family had endured.

Facebook had only taken the accounts down when Corrales reported the incidents. He needed information about the accounts to take legal action against the online attackers.

Corrales' complaint is the first attempt by a Filipino journalist to hold an international tech platform accountable for online attacks. Corrales is seeking a total of P20 million ($358,000) in damages.

Corrales, associate editor of the Mindanao Gold Star Daily, had earned the distinction of being one of the most “red-tagged” journalists in the Philippines for his articles that were critical of the government.

In 2019, Corrales hid at a friend's house after a wanted poster with his face on it and a P1M reward ($18,000) was mailed to the Cagayan de Oro Press Club. His wife and son were also red-tagged (the tag is often seen as synonymous with being New People's Army (NPA) communist rebels, much like a scarlet letter) and they were labelled a “family of communists”.

“Until now, we can’t sleep well at night. When we are out together, we always keep our distance from each other for fear of an attack. In case something happens, at least one of us will be left to take care of the family,” Ailyn, Corrales’s wife, said in an interview with Rappler.

Both Corrales and his legal counsel, Tony LaViña, declined to comment further on the case so as not to prejudice its outcome.

A climate of fear

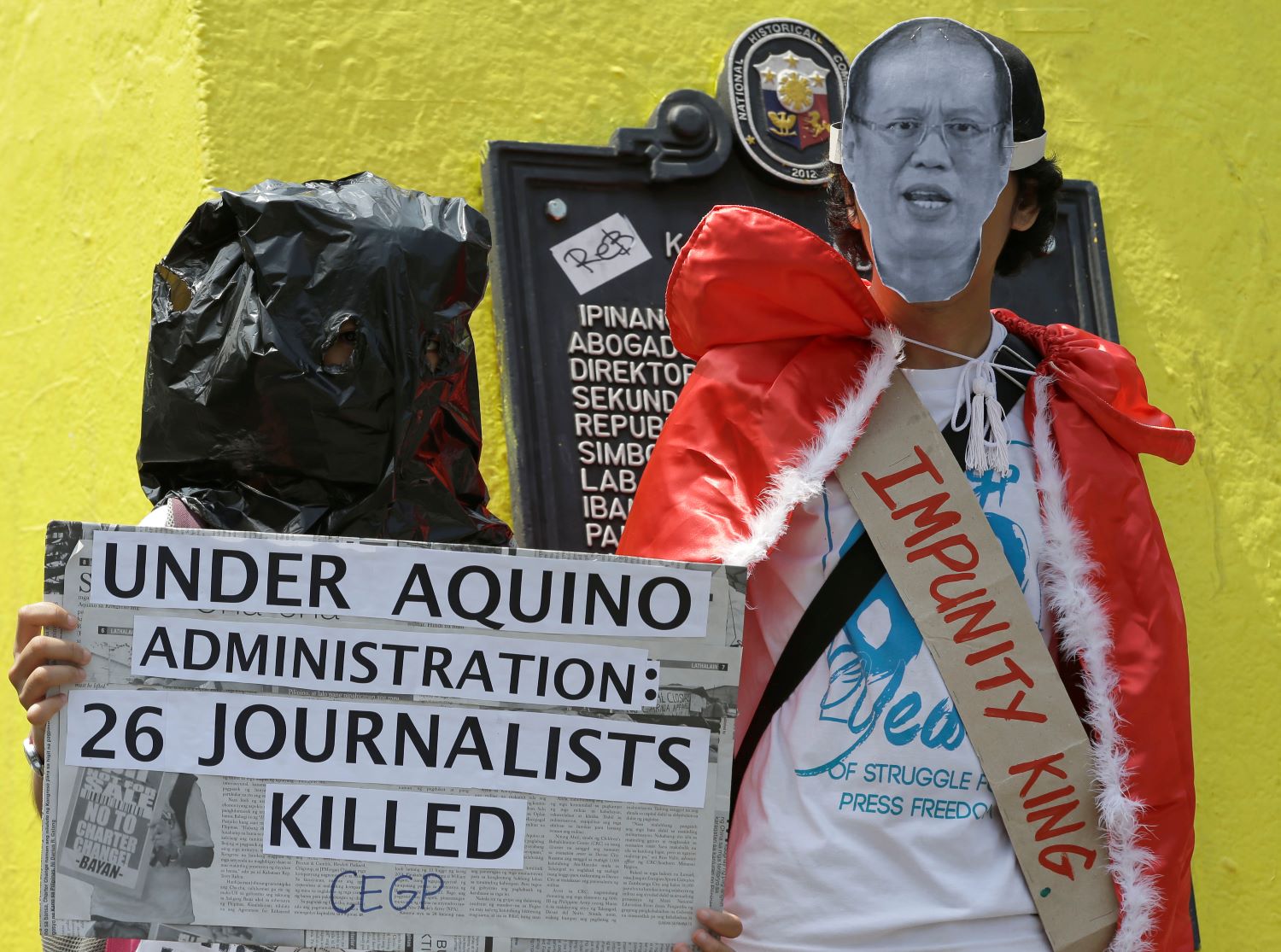

For years, the Philippine government has used “red-tagging” or the labelling of groups and individuals as communist “fronts” or being part of a communist movement in its counter-insurgency programmes. Under the administration of former president Rodrigo Duterte, red-tagging became an official government policy.

The National Task Force on Ending Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), armed with a budget of P10BN ($179M) has been very busy, red-tagging human rights defenders, journalists and once even a gold medal Olympian.

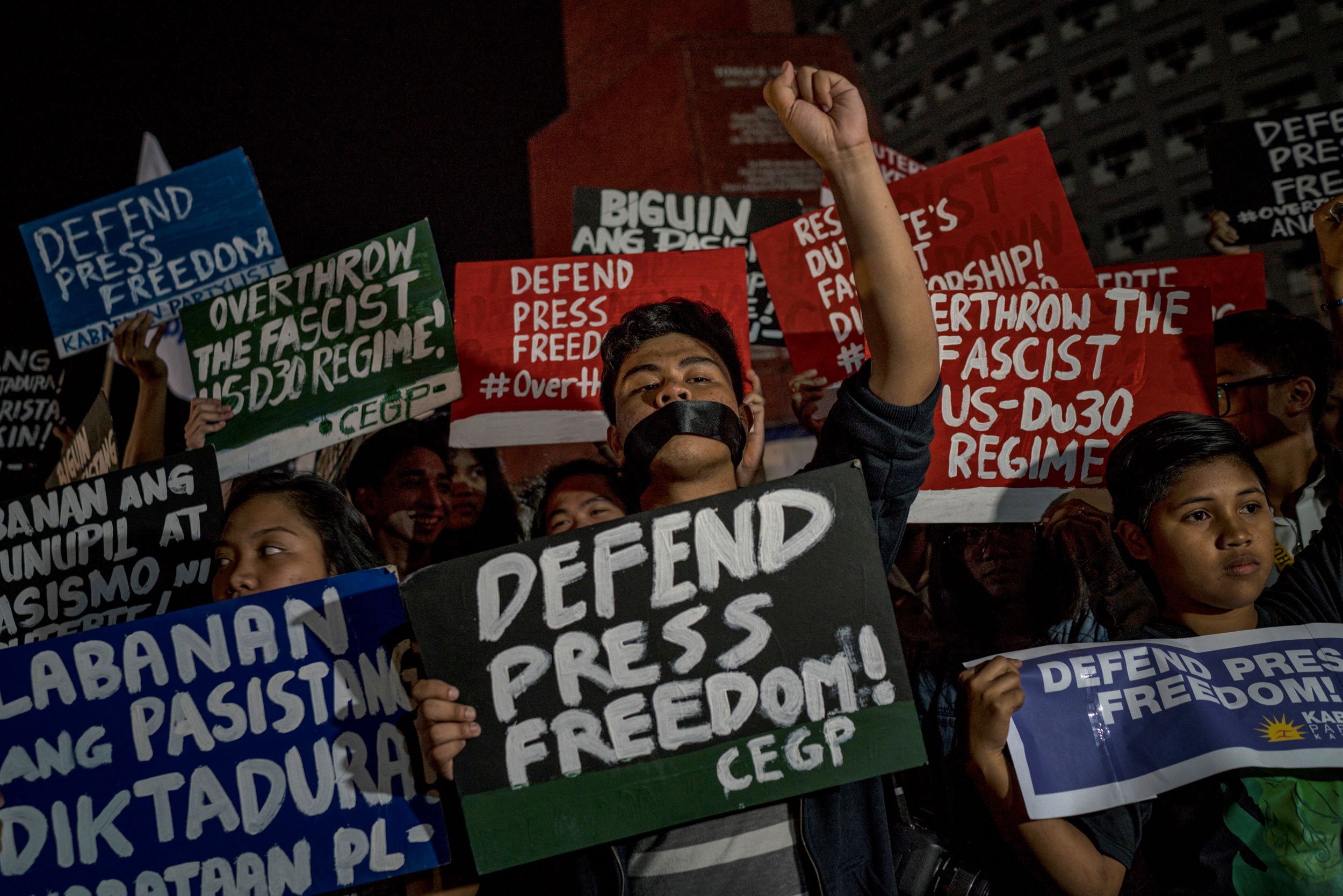

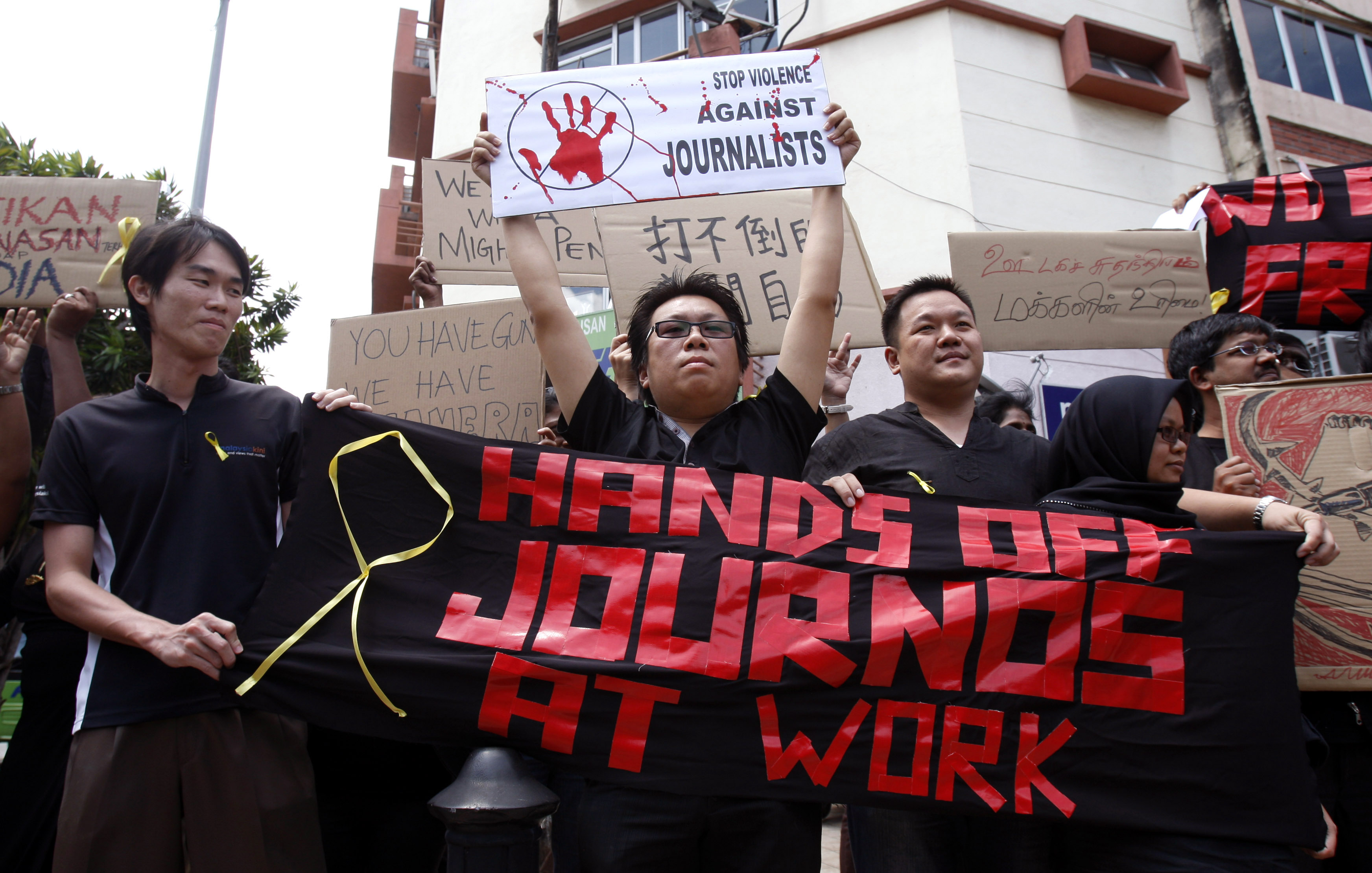

Online attacks fuelled by troll armies and legitimised by disinformation, private ownership of news outlets and local political rivalry have made the Philippines, once perceived as the most free and vibrant media market in Asia, one of the most dangerous places to be a journalist.

In 2009, a political rivalry between two families in the southern Philippine island of Mindanao resulted in 58 people being fatally shot and buried in shallow graves with a backhoe. Among those killed were 32 journalists. What is now known as the Ampatuan massacre (named after the family convicted of the murders) stands as the single deadliest incident of violence against journalists in the world.

Red-tagging enabled by the Anti-Communist Insurgency Law has made matters worse.

“If we compare our situation then and now, it’s getting worse and really, we are in danger. Journalists like us do not have any backers, the legislature left us, and the government attacked us,” said radio broadcast journalist Lourdes Escaros.

The result is a climate of fear and doubt. “There is a chilling effect. You might be red-tagged for a story. You ask yourself, is it worth it? Life of journalists is cheap in the Philippines, it’s so easy to kill them,” said Escaros.

“You will question if it is worth it when you have to consider your security and your safety,” Escaros added.

Private ownership - an Achilles heel

Complicating the matter is private ownership of media organisations. ABS-CBN and GMA, the two largest media networks, are owned by wealthy families who have an array of business interests that are heavily regulated by the government.

A Reporters Without Borders (RSF) report has warned of the perils of having media ownership concentrated in the hands of the wealthy few - with good reason.

In an interview, Sheila Coronel, Director for the Columbia University Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism in New York said: “Media ownership has always been the Achilles heel of press freedom in the Philippines.”

The tendency to temper news reports or censor them comes from journalists who want to protect themselves and media organisations whose owners want to protect their business ventures.

It was in this precarious setting that the government stepped in and used existing laws to legitimise political bullying.

After the Philippine Daily Inquirer published photojournalist Raffy Lerma’s photo of a woman clutching the body of her partner shot dead in a drug war on its front page in July 2016, Duterte lost no time castigating the paper and its owners in his speeches. He took it a step further and accused the newspaper of owing P8 billion ($144 million) in unpaid property taxes.

In 2017, the Prieto family, owners of the Inquirer, sold their controlling shares to Ramon Ang, a wealthy businessman and Duterte ally.

In the face of the blatant intimidation, as reported in Rappler, behind the headlines, Inquirer editors found themselves constantly weighing up the news-worthiness of a story against any possible further aggravation of the Prieto family.

At the height of the 2020 outbreak of COVID-19 when people isolated in their homes depended on news agencies and social media, Congress shut down ABS-CBN by voting not to renew its corporate franchise. Many called it a case of political vendetta. The former president had an axe to grind with the network for allegedly failing to broadcast his campaign ads.

More than 11,000 people lost their jobs and millions of Filipinos lost access to television and radio news and entertainment.

“The gap left by the closure of ABS-CBN created a vacuum. Some correspondents put together a network and started broadcasting on Facebook. But it also gave rise to networks with particular biases,” said Jonathan de Santos, chairperson for the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

According to the latest Reuters Digital News Report, while television remains the most popular source of news, Filipinos get their news from a combination of television and social media with Facebook being the most widely used at 75 percent for news weekly.

'The most difficult time to be a journalist'

Veteran journalist and Pulitzer Prize Winner Manny Mogato says in his over 40 years of journalism, the last decade presented a triple whammy for Philippine media.

“I think this is the most difficult time to be a journalist,” says Mogato.

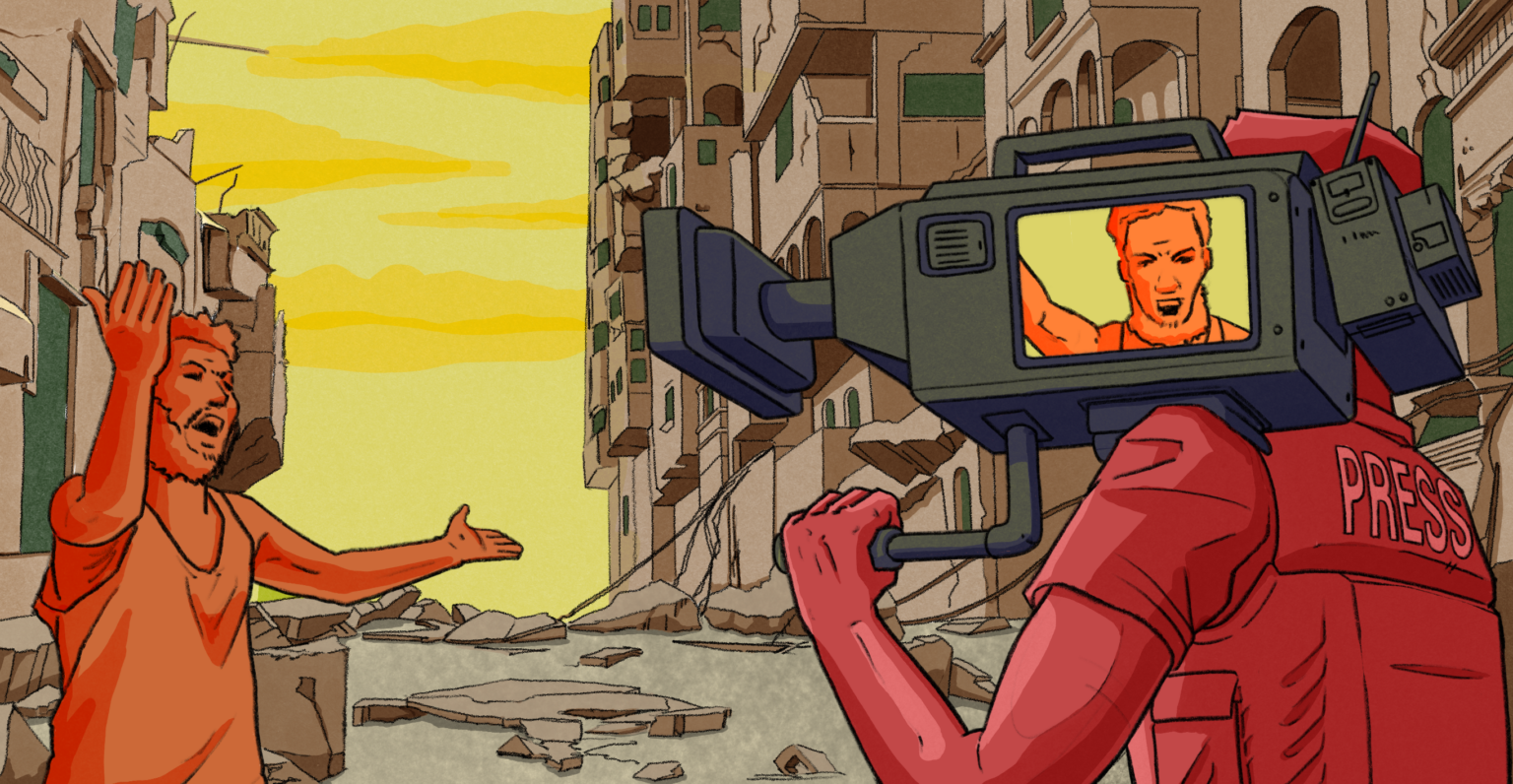

First, there was the continuing impact of the digital age that caused media revenues to plummet, the widespread disinformation that journalists have to counter in the face of their own dwindling credibility, and the relentless online threats that can lead to real life violence.

Then came Duterte who said that “corrupt” journalists deserve to be killed.

Mogato had experienced his own share of threats and intimidation when he was assistant editor for the Manila Times. In 1999, former president Joseph Estrada sued the Manila Times over a corruption story. Months later, the paper was sold to an Estrada ally.

“But Duterte is more vicious and dangerous,” says Mogato.

During the term of Duterte, which ended in 2022, there were 223 reported cases of threats and attacks against the media, and 23 journalists were killed.

Even before the Pulitzer Prize winning Reuters investigation on the state-sanctioned drug war was published, Mogato was already a target of online threats for stories that pointed out government abuse of power.

When the story was published, Mogato and another reporter were billeted in a hotel and did not report to the office. A Reuters security team from Hong Kong checked their security risks at home, had a CCTV installed in their house, and taught them counter security measures. They varied their travel routes to ward off possible surveillance.

“We were very cautious about our safety. We were up against Duterte and his government,” says Mogato.

Cautious optimism

Now, a little more than a year under the administration of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr, the son of the former dictator who ruled the Philippines more than 20 years, there is cautious and sceptical optimism.

“Compared to Duterte where we were really coming from the pits, any administration would look better,” says Chay Hofileña, head of the Rappler investigative desk.

Like the Inquirer, Duterte targeted Rappler in his public speeches, for its critical reportage of the drug war.

In 2019, Maria Ressa, Rappler’s chief executive and co-founder, was charged with as many as a dozen cases at one point, ranging from cyberlibel to tax evasion. In January this year, Ressa was cleared of four tax evasion cases which would have landed her with more than 30 years in prison.

Ressa and the news agency she co-founded face three more legal cases, including a Supreme Court appeal on a cyberlibel conviction in 2020.

The Rappler newsroom faced closure when the Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission moved to revoke its operating licence and is appealing the shutdown order.

Ressa was awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize for Rappler’s reportage on the drug war and its documentation of how social media is used to spread fake news and manipulate public discourse.

There is more semblance of a democracy under Marcos, Jr but Hofileña is quick to emphasise the word “semblance”.

Marcos, Jr has kept a cordial but somewhat distant relationship with the press. Media are invited to cover his official state visits, but the opportunities to question and critique government policy by directly questioning the president are regulated. One reporter covering the presidential beat told Al Jazeera Journalism Review that Marcos, Jr has not conducted regular press conferences at the Palace. Usually, his cabinet officials hold press conferences and field questions from the media.

“We are still feeling the remnants of the culture of fear Duterte successfully created. The feeling of fear has somewhat lifted but it is still a wait-and-see type of attitude. For example, the NTF-ELCAC (anti-insurgency government body) is still there. So the question is when Marcos, Jr will use it or if he will use it,” says Hofileña.

Groups like Lawyers Against Disinformation and #FactsFirstPH, a coalition of organisations from different sectors fighting disinformation through rigorous fact-checking and taking legal action when necessary, have come out in support of journalists and freedom of the press.

“One of the lawyers told us: ‘It cannot just be journalists at the frontlines. We have to support you. We cannot do without you.’ That was encouraging and heartwarming,” said Hofileña.

Foregoing the journalism dream

For some aspiring journalists, the disillusionment with the profession that began with the disinformation that chipped away at public trust in the media and the ensuing hate targeted at media practitioners was enough to make them re-assess the viability of a career in journalism.

Watching the news every night over dinner with her family, Elaine Dico once dreamed of becoming a journalist. But, having just graduated with a journalism degree from the University of the Philippines, Dico has foregone working in the newsroom for a corporate desk.

“If I saw that being a journalist was safe, financially and politically, I would have pursued it.

"With journalism now, I honestly have no idea where I will be in five years. If I will have a job or not. If I will be dead or alive,” she says.

Rambo Talabong, an award-winning multimedia journalist, posted on his LinkedIn profile that he has repeatedly encountered similar sentiments in forums with journalism students.

“One question that they repeatedly ask is: How do you continue to stay in journalism when you've been so antagonised and distrusted?” wrote Talabong.

Talabong has re-framed what dedicating his life to his profession looks like by spending more time with loved ones, taking time to rest, and appreciating the small ripples of impact, like a grateful reader who sends a message thanking Talabong for clarifying an issue.

“It reminds me that even with all the hate and distrust, there are people in the world I can turn to who will advocate for me and will continue to cheer me on as I stay in this difficult profession,” wrote Talabong.

![A demonstration against Israel's war on Gaza on Paulista Avenue in São Paulo on November 4, 2023, draws attention to the deaths of children while the media focuses on the war against terrorists. [Photo: Lina Bakr]](/sites/default/files/ajr/2024/Picture1.png)