This article argues that the Palestinian context exposes the colonial roots of traditional journalism and calls for a decolonial approach that centers marginalized voices, promotes collaborative reporting, and demands structural change within newsrooms to uphold journalistic integrity.

It must have been around 17 years ago when my then Dutch-Moroccan colleague Hassan casually mentioned that he supported the Palestinians. A small moment by the office coffee machine, where many workdays begin. A little shock went through me at the time; supporting Palestine, in my mind, was synonymous with wanting to destroy Israel.

Ten years before that, my high school best friend and I spent a gap year travelling through Israel, Jordan, Egypt, Greece, and Turkey. During five months in Israel, we were advised to “not engage with Arabs” and to avoid the West Bank. I found the Israeli people extremely guarded, at times rude, and overwhelmingly preoccupied with safety. But, if there’s a threat, I thought, they have a right to defend themselves. Who was I to question that?

In the 18 years leading up to that trip, I was raised as a Protestant Christian in the Netherlands, where Israel was often revered as the promised land. Dutch politicians regularly invoked so-called Judeo-Christian values as foundational to our society. Hassan, however, came from a Muslim background and had been exposed to different narratives, perhaps through the books of Edward Said or the journalism perspective of Al Jazeera. His expression of solidarity with Palestinians was the first small fracture in my understanding of the issue.

That early crack widened over time. Today, I view the reporting on the humanitarian crisis in Gaza through a different lens, particularly in Western mainstream media, which often frame the Palestine issue with a narrow, colonial mindset that disregards the history and suffering of Palestinians in favour of narratives that uphold the interests of Israel, backed by the powerful West.

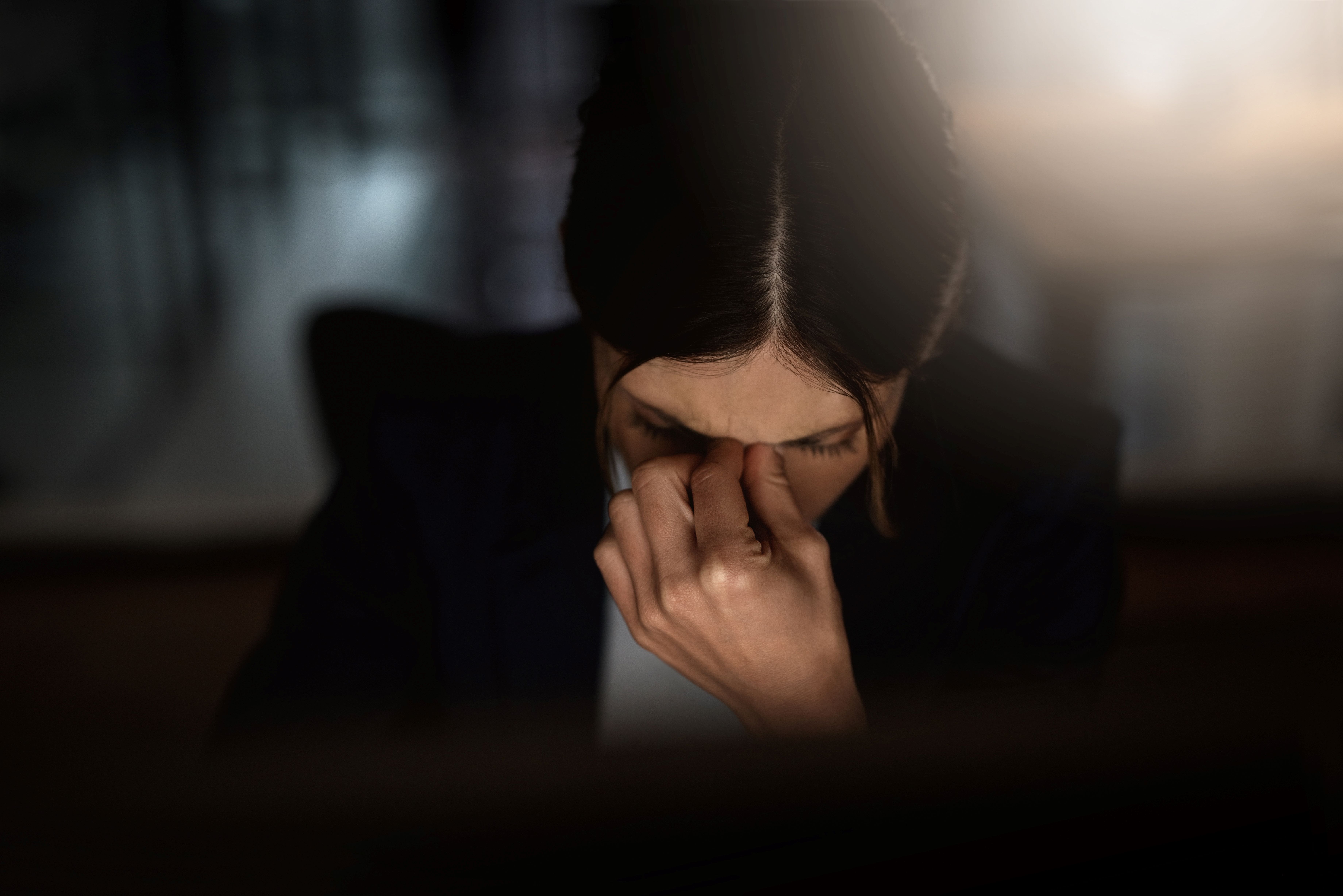

Palestinian struggle should have planted many seeds of reflection in the minds of many journalists, just as Hassan’s words planted one in mine. Ignoring those seeds doesn’t just numb the conscience; it erodes the integrity of the profession.

From “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) to Decoloniality

Hassan and I worked for FunX, a media organisation that prioritised diversity, and the staff was a representation of the culturally diverse audience that we targeted. It was a positive exception in the primarily white Dutch media landscape. Right after the killing of George Floyd by police violence in the US five years ago, calls on media organisations to engage in antiracist practices and for more transformative action through “decolonisation” became increasingly louder. Many Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives were set up, together with debates about the role of objectivity in white-dominated newsrooms that failed to represent Black communities accurately.

Despite progress, racial diversity among journalists in countries like the US, Canada, and across Europe remains limited. (Sources: PEW Research, 2023; Canadian Association of Journalists, 2024; Reuters Institute, 2025.) It’s still rare for white journalists to have colleagues from different racial backgrounds; rarer still that colleagues feel safe enough to challenge the status quo, for example, by expressing open support for Palestine. By late October 2023, several journalists had already been fired over pro-Palestinian remarks, illustrating the risk journalists face.

Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement started as a response to police brutality and systemic racism in the United States, but its worldwide resonance led to deeper conversations about the media’s role in ongoing colonialism, imperialism, and historical injustices in many parts of the world, including Palestine.

To understand how Palestine is pushing Western media toward decolonisation, we first need to explore what "decoloniality" means in the context of journalism. Unlike political decolonisation, which refers to the formal transfer of power from colonisers to formerly colonised nations, decoloniality goes deeper. Coined by Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano, the term challenges the underlying systems of knowledge and power that continue to shape societies, even after independence. In journalism, this means questioning whose voices are heard, whose perspectives are prioritised, and how narratives are constructed.

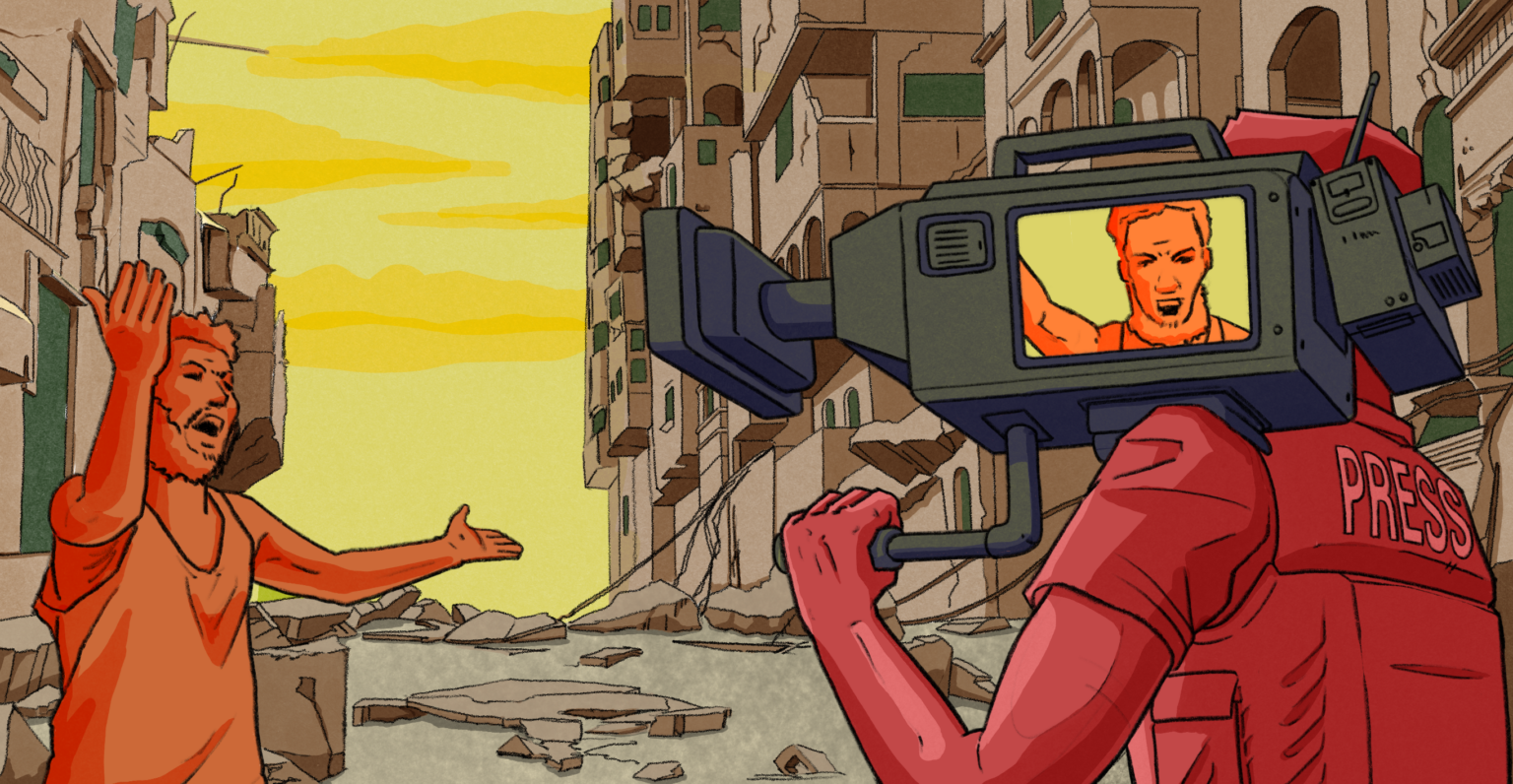

For journalists, it means recognising the enduring impact of colonial histories and how the colonial ways of thinking and operating still influence our societies today. Colonialism was able to sustain itself for so long and to persuade the masses to be part of it through falsely representing others. Media has been weaponised to export specific images of colonised countries to uphold colonialism and has incorporated its extractive practices.

Decoloniality confronts these systemic injustices and goes beyond DEI policies by challenging the underlying structures that perpetuate inequality in how stories are told and whose voices are valued.

The Palestinian journalists have demonstrated that, despite the Israeli government’s scandalous refusal to allow foreign reporters into Gaza, powerful and accurate reporting can still emerge from within the community itself.

Applying Decoloniality to Journalism

The war in Gaza has brought issues to the surface that directly connect to colonialism, such as the ongoing legacy of the Palestinian displacement, oppression and denial of basic human rights under Israeli occupation. It has also underscored the colonial nature of global media coverage in which Western mainstream media newsrooms often frame the conflict through a both-sided lens.

Hassan’s comment had planted a seed in my thinking, one that eventually resonated with how Dr Catherine E. Walsh describes decoloniality:

“It is like the seed that cracks concrete. It’s not an assurance, not a condition or a new model. It’s an indicator of creative possibilities, against coloniality but also for new practices and alternatives.”

Her description captures the essence of what is needed in journalism today: new practices that dismantle colonial ways of thinking and open space for fairer, more just narratives.

While decolonial theory often comes cloaked in academic language, the core idea is quite accessible. It begins with recognising our positionalities as journalists. Where do we stand in terms of race, class, gender, education, religion, ableism, and other societal categories? What blind spots might arise from our positions?

For example, as a white woman, with the privilege of a high education, raised Christian in a “former” colonising country, I know I likely have blind spots towards issues outside the value system I was raised in. Acknowledging my Western European positionality as just one lens among many is crucial to striving for fairness in reporting. It allows me to challenge the traditional notion of objectivity, to consider whose truths are centred, for whom it is told, and from what perspective.

Media has been weaponised to export specific images of colonised countries to uphold colonialism and has incorporated its extractive practices.

Secondly, the global newsroom structures and reporting practices have largely developed within the Western framework and mindset, thus partly rooted in colonial ways of thinking. Take for example the practice of sending reporters from the West to cover stories in the Global South and marginalised countries. This approach is often referred to as parachute journalism, and the practice of extracting stories, perspectives and experiences from these communities without crediting or compensating them fairly. The result is a one-sided, exploitative relationship, like the (ongoing) extraction of resources, labour, and knowledge during colonial times, disregarding the rights of the local population.

The Palestinian journalists have demonstrated that, despite the Israeli government’s scandalous refusal to allow foreign reporters into Gaza, powerful and accurate reporting can still emerge from within the community itself.

To make decoloniality in journalism more tangible, we can reimagine how newsrooms operate by making concrete changes, such as:

- Implementing hiring practices that prioritise diversity of voices in the newsroom

- Centring marginalised voices in the stories and surfacing histories and perspectives erased or silenced by colonialism.

- Rethinking editorial decision-making processes to include a wider range of perspectives.

- Using language that avoids stereotypes and portrays all people with dignity and agency.

- Offering continuous education and training on systemic bias and encouraging self-reflection in reporting.

- Shifting from extractive models of journalism toward more collaborative approaches that involve the communities being reported on.

Decolonising journalism isn’t just about awareness or panel discussions at conferences; it requires concrete action.

From Reflection to Action

Creating space for reflection within the fast-paced news cycle is essential. Even setting aside just one hour a week to review recent stories and examine narrative framing can make a meaningful difference. We already do this for social media analytics or AI policy reviews—why not apply the same intentionality to editorial direction?

If society is a concrete wall, we may not be able to tear it down instantly, but we can create cracks. Many media organisations are already doing this. Dutch magazine OneWorld developed a language policy to remove colonial terms from its reporting. For example, instead of “giving people a voice”, they choose to “give people a stage” because everyone already has a voice. And instead of using the term “minority” in cases when they aren’t really minorities, they now choose to say, “marginalised people”. In North America, Democracy Now! continues to centre indigenous and Palestinian voices to ensure that their perspectives are recognised as valid, rather than being sidelined and misrepresented. Centring these voices creates a shift from portraying marginalised people as passive victims to a focus on agency and resistance. And the Israeli-Palestinian media organisation +972 Mag has created impactful investigations in collaboration with Western outlets, showing the power of collaborative journalism.

By now, the Palestinian struggle should have planted many seeds of reflection in the minds of many journalists, just as Hassan’s words planted one in mine. Ignoring those seeds doesn’t just numb the conscience; it erodes the integrity of the profession. Decolonising journalism isn’t just about awareness or panel discussions at conferences; it requires concrete action. It means asking ourselves; who is telling the story? Who is it for? And what values are guiding our work?

References:

- Amnesty

- On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, Mignolo, Walter D. and Katherine E. Walsh. Duke University Press, 2018.

- Decolonizing Diversity: The Transnational Politics of Minority Racial Difference. Hundle, Anneeth Kaur. Public Culture, vol. 31, no. 2, 2019.

- Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups, Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun, 2001.)

- Interview with sociologist Ruha Benjamin on Trevor Noah’s What Now? podcast.

- The Complicated History Behind BLM's Solidarity With The Pro-Palestinian Movement, NPR, June 12, 2021

- Notes from the Maria Lugones Summer School on Decoloniality I attended in 2021.

- What journalism needs to change to meet the needs of the Global South, panel discussion at International Journalism Festival