India’s crackdown on X-Twitter accounts documenting hate crimes highlights the increased risks faced by journalists who report on these issues. The suppression of such accounts significantly hampers the ability of journalists to access and report critical information on hate crimes.

In India, those who document hate crimes and hate speech are more at risk of the regime’s actions than those who commit them

In recent months, social media giant X (formerly Twitter) has blocked the accounts of several U.S.-based human rights organisations at the behest of the Indian government. Among these are Hindutva Watch, India Hate Lab, the Indian American Muslim Council, and Hindus for Human Rights. These organisations have been pivotal in documenting and exposing anti-Muslim hate crimes and hate speech by Hindu nationalists in India.

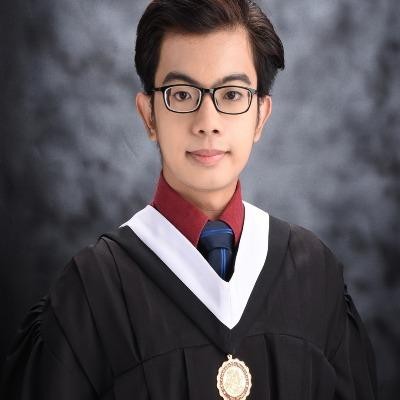

Raqib Naik, an Indian journalist and founder of Hindutva Watch, emphasised the risks faced by those documenting hate crimes in India during his keynote speech at the Oslo Freedom Forum 2024. "In India, those who document hate crimes and hate speech are more at risk of the regime’s actions than those who commit them," Naik stated. He highlighted the rise in hate speeches, attacks on the free press, and censorship under Prime Minister Narendra Modi's rule.

Journalists Denied Access to Critical Information

The pervasive suppression of social media accounts documenting hate crimes in India has cast a long shadow over the landscape of journalism, significantly impacting the work of journalists.

Most mainstream news organizations in India either ignore or justify hate crimes. Only a few independent outlets report on them, often using leads from social media platforms like Hindutva Watch.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, Naik explained that the censorship of information on hate crimes on social media is severely undermining the ability to report on these incidents. "By blocking accounts and removing content that documents hate crimes, the authorities are denying journalists access to critical information," Naik said.

Waquar Hasan, a journalist affected by these restrictions, highlighted the difficulty in reporting hate crimes due to account bans. “Most mainstream news organisations in India either ignore or justify hate crimes. Only a few independent outlets report on them, often using leads from social media platforms like Hindutva Watch. With the current restrictions, even these few independent outlets struggle to report on such incidents,” he told Al Jazeera.

Hassan believes that the absence of information on hate crimes is almost complete, and reports on violence against Muslims and other minorities are rare, even though such incidents occur daily.

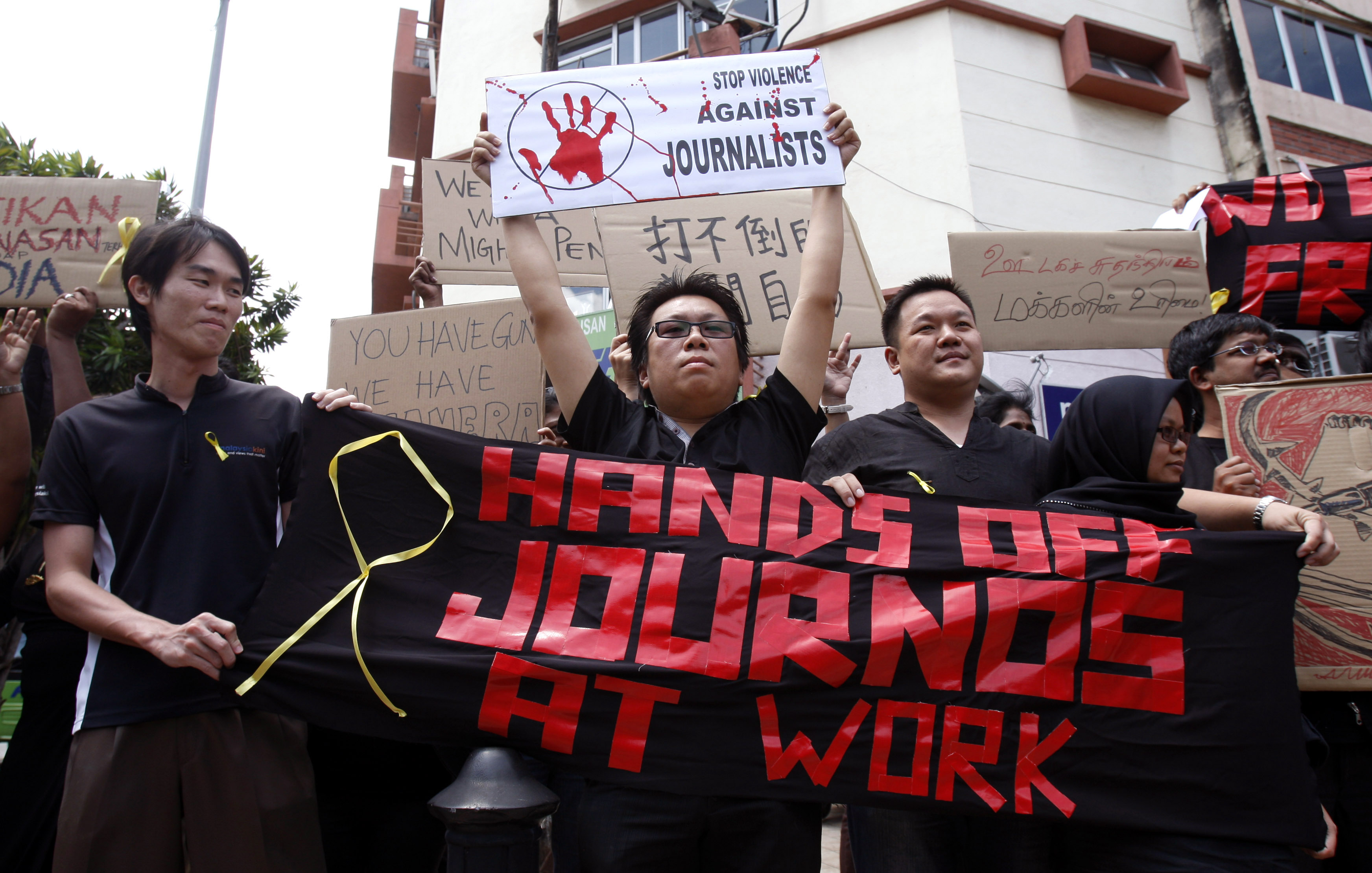

Growing Risks for Journalists

Journalists, who rely on platforms like X to disseminate their reports and reach a broader audience, find themselves navigating an increasingly hostile environment where the act of reporting on hate crimes can invite severe repercussions.

In October 2023, the X account of Meer Faisal, an award-winning Muslim journalist who extensively reports on hate crimes in India, was ‘withheld’ in India based on a request from the government. Meer has a following of over 50k on X, and his news stories are frequently covered by various media outlets, with some having significant impact.

“Press freedom is in jeopardy, and journalists who report on Muslim-related stories face significant surveillance. Journalism should not be treated as a crime,” Faisal told Al Jazeera.

He explained that it has become increasingly difficult for journalists to do their jobs with limited reliable online resources and the constant pressure of censorship.

Press freedom is in jeopardy, and journalists who report on Muslim-related stories face significant surveillance. Journalism should not be treated as a crime

In July, police in India’s Uttar Pradesh state booked two Muslim journalists, Zakir Ali Tyagi and Wasim Akram Tyagi for sharing information about the alleged lynching of a Muslim man, on social media.

"The act of reporting or documenting either a hate crime or hate speech has unofficially become a criminal act. It’s unfortunately the new reality under which journalists and hate trackers have to operate. For them, the distance between freedom and jail is becoming narrower with each passing day,” Naik explained, highlighting the growing risks for journalists.

This climate of censorship and intimidation forces journalists to operate under constant fear of retaliation. The threat of having their accounts suspended or facing legal action for merely documenting hate crimes deters many from reporting on these critical issues.

A prominent journalist who routinely reports on communal violence in India, speaking on the condition of anonymity, explained how right-wing analysts have justified this clampdown by pointing out that India is a communally sensitive country where sharing a morphed narrative can lead to mob violence.

“At the same time, we see social media accounts, often followed by government officials, who spread all sorts of inflammatory disinformation, face no action by the government. But accounts who thoroughly fact check their posts can easily land in trouble,” he pointed out.

The act of reporting or documenting either a hate crime or hate speech has unofficially become a criminal act. It’s unfortunately the new reality under which journalists and hate trackers have to operate

Lack of Accurate Reporting on Hate Crimes

The impact on journalism is not just immediate but also long-term. The systematic silence of dissenting voices and the suppression of critical reporting erode public trust in the media.

Hassan explained that when mainstream media organisations do report on these incidents, they often portray the victim as being at fault, with some media outlets even justifying crimes against Muslims and other minorities.

"In the absence of thorough reporting on hate crimes, supporters of the current regime and Hindu nationalism spread hatred and misinformation to vilify Muslims. As a result, the larger audience perceives Muslims as troublemakers rather than victims of violence and hate," he explained.

According to Suchitra Vijayan, an author and founder of The Polis Project, a New York-based research and media organization, “When important stories about hate crimes and human rights abuses are not reported, the public remains unaware of the full extent of these issues, and the perpetrators are emboldened by the lack of accountability. This creates a vicious cycle where unchecked hate crimes continue to proliferate, and the journalistic profession is further undermined.”

Naik states that shutting down Hindutva Watch and India Hate Lab also deprives the public in India of crucial information about politically motivated sectarian and religious violence and also hampers law enforcement's ability to investigate these crimes. "We've had local police contact us to use our documentation for investigating violence," he says.

India's ranking in the 2023 World Press Freedom Index slipped to 161 out of 180 countries, a significant drop from its 2014 position at 140. Modi’s government has been criticised for suppressing tweets, posts, and user accounts critical of the ruling party and its policies. The blocking of Hindutva Watch and India Hate Lab is seen as a move to control the information space as the country slides further into authoritarianism.

The Blocking Orders

On January 16, Naik received a notice from X that Hindutva Watch's account had been blocked by order of the Indian Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY). Similarly, in October 2023, X withheld the accounts of the Indian American Muslim Council and Hindus for Human Rights in compliance with a legal demand from the Indian government. Despite the lack of explanation for these actions, the implications are clear: these organisations are being silenced.

Hindutva Watch is the only operational digital database in India that tracks hate crimes and speeches against marginalised groups. In 2023 alone, the site documented 668 anti-Muslim hate speech events and rallies, with a significant portion advocating violence, including ethnic cleansing and genocide.

According to the latest report released by India Hate Lab before it was blocked in India, nearly two anti-Muslim hate speech events took place every day in 2023, with around 75% of those occurring in states ruled by the BJP. The cases peaked between August and November 2023, during political campaigning and polling in four major states.

Naik has challenged the blocking of Hindutva Watch’s X account in Delhi High Court. At the time of its blocking, the account had over 79,000 followers. Naik was not provided prior notice, a hearing, or a copy of the blocking order.

When asked about the suspensions, IAMC’s Associate Director of Media and Communications, Safa Ahmed, said, "It was deeply concerning, but not at all surprising. After all, it’s not just IAMC being targeted on social media; now more than ever, India is cracking down on all its critics, from giants like the BBC to individual activists and journalists."

In 2023, Modi’s government raided the offices of the BBC in India—ostensibly over a tax issue—weeks after Britain’s national broadcaster had aired an investigative documentary highlighting his complicity in riots that killed more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, in Gujarat while he was the state’s chief minister.

Legal and Ethical Concerns

The government issued suspension notices under Section 69A of the IT Act, which empowers authorities to block public access to information in the "interest of sovereignty, integrity, and security" of India. However, experts argue that this law is being misused to suppress dissent.

According to Mishi Choudhary, a lawyer and general counsel at Virtru, MeitY has used the IT Act and rules to establish a “system of censorship.”

Since billionaire Elon Musk assumed control of X in October 2022, the company has increasingly complied with government requests for censorship and surveillance. Between October 2022 and April 2023, tech policy outlet Rest of World reported that X did not reject a single government demand globally, a stark contrast to its previous stance when it sometimes pushed back against censorship orders.

"The laws governing these blocking orders are especially insidious because the government does not need to explain what makes a website, account, or content dangerous or violative, making it challenging for platforms, ISPs, or users to contest them," she told Al Jazeera.

India’s use of censorship has surged under the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government. In a written response to Parliament in December 2023, MeitY reported blocking 36,838 URLs between January 2018 and October 2023, with the highest number of blocks occurring in 2020.

X, the focal point of political conversations, saw the highest number of blocks in these 70 months—13,660.

Since billionaire Elon Musk assumed control of X in October 2022, the company has increasingly complied with government requests for censorship and surveillance. Between October 2022 and April 2023, tech policy outlet Rest of World reported that X did not reject a single government demand globally, a stark contrast to its previous stance when it sometimes pushed back against censorship orders.

Continuing to Report Despite Restrictions

Naik and others worry that blocking these platforms will hinder the documentation and reporting of hate crimes in India. However, despite the suspension, Naik remains undeterred, continuing his work in documenting human rights abuses.

"We are still following our usual routine. We post videos on our social media handles and website. It’s still making its way to the Indian social media ecosystem. People are using different tools to access our website and handles."

Despite the gag, IAMC's Instagram account remains accessible in India, and they continue to maintain a significant following among the Indian diaspora. “We are not deterred by the Indian government’s attempts to silence us,” Safa said.

The resilience and courage of journalists who continue to document and expose hate crimes are commendable. Despite the risks, they persist in their efforts to ensure that the truth is not buried under a blanket of censorship.

As the Modi government continues to tighten its grip on dissenting voices, the role of journalists and human rights organisations becomes ever more crucial in exposing the truth.

As Safa puts it, "Censorship creates a chilling effect. It sends journalists and activists a clear message: 'your content is being monitored, and we don’t like it.' It’s aimed at frightening those who spread information and keeping those who receive that information in the dark. In the long term, this serves to crush dissent, which is vital for a healthy and free democracy."