The upcoming U.S. presidential election occurs against the backdrop of the ongoing genocide in Gaza, with AJ Plus prioritising marginalised voices and critically analysing Western mainstream media narratives while highlighting the undemocratic aspects of the U.S. electoral system.

Americans go to the polls on Nov. 5, a story that typically dominates global news headlines for many weeks. At AJ+, our approach to covering this election begins with the unique value proposition of the Al Jazeera brand in the international media landscape—an editorial identity centred outside of the West, in the Global South.

To understand what differentiates us from the leading Western media outlets, we need only compare our coverage of the Gaza genocide with theirs. Western media routinely dehumanises the victims of Israeli bombardment, follow the narratives of the occupier, decontextualises the crisis, and erase its colonial history. Our coverage is distinct because it centres on amplifying the voices of the powerless, telling the human story of the dispossessed and traumatised Palestinians. And we offer our audiences the tools and knowledge to understand events in their context and history. Simply humanising and contextualising the story challenges the narratives of the powers—and the media outlets—abetting the genocide.

But what does any of this have to do with our approach to the U.S. election?

Quite a lot, actually.

If we’re sceptical of the narrative shaping their coverage of the U.S. relationship with Palestine and the Arab region, shouldn’t we also at least critically examine their narratives about their own system? We don’t compartmentalise reality —the United States aiding and abetting the genocide and the United States that will elect a new President on November 7 are the same entity.

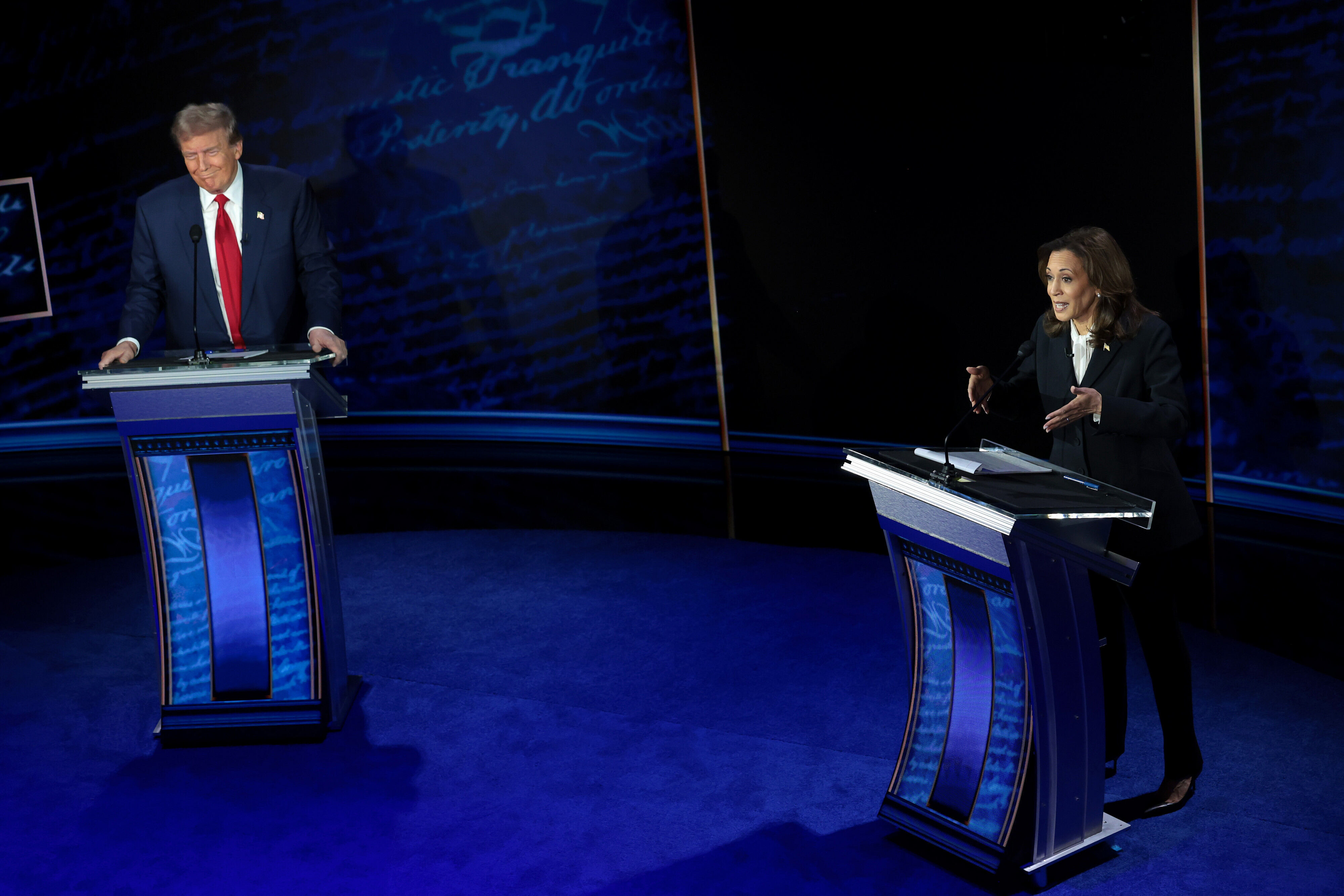

Journalists in the spin room watch the ABC Presidential Debate

The Palestine genocide has been our central focus for the past year, and it frames how we think about the U.S. election. We’re more concerned about the mayhem the U.S. is unleashing on the Global South, far away from its voting booths, than we are about the antics of competing candidates in an electoral system whose discourse and idiom conform to the norms of entertainment media.

What Could the Election Change?

Still, isn’t this election an important indicator of what the world can expect from the superpower over the next four years? A fair question, perhaps, if U.S. foreign policy was actually decided in elections—but that much is far from clear.

U.S. Presidents routinely make policy decisions quite different from what they promised on the campaign trail. Nor are the presidential campaigns centred on serious policy debates —perhaps one or two “wedge” policy issues that divide key voting blocs (abortion, immigration), but for the most part they’re conducted in the language of advertising, conjuring sentiments and “vibes” (fear/anger vs. optimism/joy in this instance) that ad-makers seek to associate with their candidate, as they would for a shampoo or a car or a burglar alarm.

Neither a Trump win nor a Harris win will significantly alter the course of Israel’s U.S.-enabled rampage in Palestine and Lebanon. They share a commitment to Israel’s criminal campaigns, even if the majority of voters oppose Israel’s actions in Gaza.

Life in America will certainly be different depending on which candidate wins. Space to protest for Palestine, for example, could be even more sharply curtailed if Trump were reelected. He is also promising a vicious racist assault on Black and Brown migrants in the U.S. and has also given women plenty of reason to fear further curbs on their access to abortion.

Trump and Harris also take different positions on the Ukraine war, though its outcome is not a primary concern for most in the Global South. But there’s no reason to expect any difference in their enabling of Israel’s wars.

Viewing the U.S. from the Outside

Our coverage seeks to help our global audience understand how the U.S. system works—not taking at face value its own proselytising as the “model democracy,” but instead explaining the frequent disconnect between the choices of the majority of its voters and the outcomes of its elections.

In 2020, Joe Biden beat Donald Trump by 7 million votes. But if only 120,000 of those voters in four key states had simply stayed home, Biden would have beaten Trump by 6.9 million votes—and been the loser. This is not an anomaly; it’s a pattern produced by the peculiar design of the U.S. system: Trump was elected president in 2016 despite finishing second by 3 million votes; George W. Bush in 2000 finished second by a half million votes. There’s no cheating involved; it’s simply the workings of the “Electoral College”, a constitutional mechanism designed to curb the will of the electorate.

The U.S. Senate is an even more extreme case — it gives two seats to every state (the equivalent of a province) regardless of population size. That means a single vote for the U.S. Senate in Wyoming (pop. 584,000) has the equivalent power as more than 70 votes in California (pop. 40 million), and the key national legislature can be controlled with less than 20% of the national vote.

Western media outlets treat these minority-rule overrides built into the U.S. system as unremarkable workings of American democracy. We prefer to highlight them for our global audience to consider against universal democratic standards. Our audience deserves a deeper and more critical understanding of how the U.S. system works, covering everything from the outsize role of billionaire donors in picking candidates, the two-party system and how it narrows the choices of voters, to the enduring legacy of America’s Founding Fathers, who expressed a fear of democracy and designed a constitution that would limit it.

Flipping the Democracy Lens

We’re mindful of the fact that if the U.S. election were judged for compliance with democratic principles in the way U.S. institutions assess elections in the Global South, it might fail its own test: Consider the guidelines for international monitoring used by the Carter Centre in many countries over the past few decades. Those state that a “genuine election” requires “the right and opportunity to vote freely and to be elected fairly through universal and equal suffrage by secret balloting or equivalent free voting procedures, the results of which are accurately counted, announced and respected.”

But do all U.S. citizens have the right and opportunity to vote freely? No, they don’t. The U.S., bizarrely for a modern nation state, has no single national set of voting laws or election commission; voting laws vary from state (province) to state. And state authorities are able to place a thicket of legal and logistical obstacles between the ballot box and poorer Black, brown, and indigenous citizens they suspect will vote against them: voter ID laws, a dysfunctional voter registration system, reduced numbers of voting locations far from where communities live, even a law criminalising the act of providing water to voters queuing for hours in the heat.

Does the U.S. comply with the requirement of “equal suffrage”? Not exactly. The disparities created by the Electoral College and the Senate prevent “equal suffrage,” which requires that each citizen’s vote is of equal value.

The U.S. system gives also politicians the power to redraw electoral districts to diminish the impact of votes expected to go to opposition parties. Of course, citizens do have recourse to the courts. It is worth remembering, though, that the Supreme Court must be ratified by a Senate that is, by its 2-senators-per-state design, effectively a chamber of minority veto. Hence today’s Supreme Court bench, whose political leanings on many issues are wildly at odds with those of the majority of Americans.

So, our perspective on the U.S. election is to examine it from the outside and from the perspective of communities marginalised from power yet profoundly affected by it: from Gaza and from Mexico, from U.S. Black communities fighting for the right to vote or Arab American communities enraged by year of liberal-establishment dehumanisation of Arabs in Palestine and Lebanon, and more.

We avoid the “horse-race” election coverage of Western outlets; it has limited (even negative) editorial value — even if Jazeera was resourced to compete effectively in the lane dominated by Western mainstream outlets. Similarly, we see neither editorial nor market-share value in following Western outlets mesmerising their audiences with the rhetoric and dissembling of the candidates or getting sucked into “culture war” spats often stirred up to distract from deeper issues, which don’t resonate with our Global South audience.

Because they’ve normalised the distortions of democracy inherent in the “Electoral College” system, Western media often tacitly dismiss the “popular vote," i.e., the choice of the majority of voters, as of secondary importance. We believe it’s essential to highlight this figure, which reflects the choice of the majority of Americans who voted. In the majority of the world’s democracies, the candidate who won the most votes would be the winner. So, even if the U.S. constitutional mechanisms of minority rule often produce a different result, we choose to focus on this number: It’s the verdict of the people.