THE LONG READ: Many journalists in Palestine only entered the profession through a need to make their suffering known to the world. So what does it take to tell stories of tragedy and personal loss to which you yourself are deeply connected while maintaining objectivity?

For many Palestinians, including myself, journalism is more than just a profession. It is the means by which we tell our stories and convey our personal experiences of life under Israel’s military occupation to the outside world.

I never imagined myself as a journalist until I became one. Where I am from, it is a profession dictated by circumstance and necessity. In the context of Israel’s military occupation of Palestine, journalism becomes a duty for Palestinians - or a burden in that we find ourselves obliged to tell our stories to the outside world. These are stories that the world will not get to hear otherwise - certainly not from the Palestinian perspective.

In this Palestinian narrative, therefore, the personal takes centre stage. Personal stories, many belonging to journalists or citizens-turned-journalists, can become the most important stories of the day.

Herein lies the difficulty of separating the personal from the professional, where journalists are themselves the subject of the news and narrative, or at least very close to it.

For many Palestinians, being objective does not mean stopping being Palestinian as telling these personal stories of loss, agony, hope, and family lies at the heart of our understanding of objectivity. The dozens of Palestinian reporters, such as video journalist Yasser Murtaja who was shot dead in Gaza in 2018 or photojournalist Nasser Ishtayeh who was wounded after being shot in the head in September this year, themselves have become subjects of the news.

Documenting our own pain when nobody else will

In my case, it was the personal experiences of my own family under Israeli siege and occupation in Gaza and the West Bank that led me to journalism.

I wrote about how Israeli forces killed my eldest brother in 2004 when he was just 17, and how my mother, Huda, gave birth to a baby boy two years later in 2006, naming him after my eldest brother.

By doing so, I shed light on an important common experience among Palestinians - that of children being named after their dead family members. From this personal experience, I was able to dig deeper into the issue to examine the psychological impact it might have on Palestinian families. And, it was through the power of my personal narrative that I was able to make more people across the globe relate to my family’s experience.

In journalism, as in any other field of reporting or research, there is still a right and a wrong, a justice and an injustice, an oppressed and an oppressor

Ramzy Baroud, Palestinian reporter

Similarly, travel restrictions imposed by the Israeli authorities on the Palestinian people have shaped their lives in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in many ways - and it is only through documenting these personal experiences that they can be brought to the attention of the outside world.

Palestinian mothers have had to give birth at checkpoints because of these travel restrictions; Palestinian students have missed their university exams because of them and dozens of students have lost scholarships waiting for crossings and borders to open or allow them to pass. However, much of the reporting by international media on the issue of travel restrictions in Palestine reduces Palestinians to statistics and numbers only.

Helping the outside world to relate

In my reporting, I have shown the impact of travel restrictions on my mother, who grew up in the West Bank and moved to Gaza in 1978 when she married my father.

Following the Second Palestinian Intifada in 2000, it took her 12 years to obtain her first permit to visit her home town of Bethlehem in 2012. In fact, my family believes that it was largely because of the media attention she received through my writing, as well as lobbying by human rights organisations, that my mother was able to see her family again at all, despite only living an hour and a half away from her home town. Gaza and Bethlehem are less than 75km (47 miles) apart.

Sadly, in 2003 and 2008, her parents passed away without her being able to bid them a final farewell.

When talking about travel restrictions, revealing the human cost of occupation - in this case giving my mother a face among the countless statistics and faceless people - is the way forward to addressing the painful cost of the occupation.

In a country such as the US, which has a huge mainland and borders, for example, it seems incredible to most to discover that my mother was unable to attend her own parents’ funerals because she needed a permit to travel a few dozen miles to her home town - a permit that was not issued by the Israeli authorities.

Through personal narratives such as this one about my mother, we can help people to relate to the collective experiences of Palestinians generally.

The power of personal stories

I have also written about my own ordeals. From struggling to leave Gaza due to the closure of the Erez and Rafah Crossings, to being stuck outside Gaza not being able to return, I have narrated my experiences.

I have written about the anxiety of waiting for the crossing to open, the fear of being stuck inside a blockaded coastal enclave or not being able to return to it. I have written about the love-hate relationship that I have with Gaza, where homesickness battles with despair about the many injustices that people suffer because of the siege, the occupation that imposes it and in some cases because of the ageing Palestinian leadership that is often too busy with its own internal rifts.

To separate reporting on the occupation from being Palestinian is not possible

Issam Rimawi, Palestinian reporter

I have also written about the other tragedies which have beset my family as a result of the Israeli occupation. In 2007, the year that Gaza’s siege was officially imposed, my eldest sister, Zeinab, became very ill and we struggled to obtain a permit for her to travel to Jerusalem for minor surgery.

When she was finally able to leave Gaza via Egypt, it was too late for her. Two days after she had the surgery, she passed away in Cairo. I wrote about her a few years later, and many people thought she had passed away when the article was published (five years later in 2012). This, once again, shows the power that personal stories can have to help people relate to the agony of families losing hundreds of their children to the siege.

When I did manage to travel out of Gaza, I was able to meet with some of my extended family, who I had not seen for 14 years, since the age of 10. I wrote about meeting my aunts and uncles in Jordan after 14 years of separation and how I had to get to know them all over again after so many years. My aunt, Jamila, did not recognise me when we met.

Writing these personal experiences has been my way of healing, documenting and telling these stories that are entirely new to many people, even those who do know about the history of Palestine. These experiences and writings are what has made me the journalist I am today.

At the time, Gaza was under attack and my family, along with my people, had to endure a 51-day destructive war, which claimed the lives of more than 2,200 Palestinians, including my childhood friend, Ayman Shokor, 25, who happened to be on the roof of his family’s house when a random Israeli shell tore through his body.

I reported about how the family wedding in Jordan - during which I was able to see some of my family members for the first time in many years - turned into a sad occasion as I was forced to mourn Ayman, my childhood friend, and the goalkeeper of our UNRWA school.

Writing and reporting was once again my way of telling the stories of my people under occupation and, this time, it was the story of my childhood friend, whose life was cut short by an Israeli shell as his mother warned him to stay closer to her.

Telling the stories of those around us

Through these writings and reports, more people from different parts of the world were able to somehow have the feeling of how Palestinians live under occupation, away from statistics and numbers. In my reporting, I found it more compelling to narrate personal stories of ordinary people where Palestinians no longer appear as numbers but rather people with real lives. In my journalism work, I found stories to be strong enough to make people relate to our own experiences under occupation and try to help when possible.

Not just my own stories and those of my family, but also the stories of other people. I wrote about Majed Alian, from Al-Nuseirat refugee camp in the Gaza Strip where I grew up, who ended up homeless because of economic difficulties. Some people who read the article were able to help him to secure his rent for six months. I felt the power of telling personal stories from Gaza once again and the possibility that these stories might bring about real change for people in need.

It is a journalist’s moral duty to tell the truth of what they witness. As long as you present the facts on the ground, then your voice as a journalist ought to be heard

Jehan Alfarra, Palestinian reporter

One issue that has always drawn my attention is that of Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails. Although there is much literature in Arabic about Palestinian political prisoners in Israeli jails, only a few people in the rest of the world really understand what this issue is about. I felt compelled to tell their stories. In 2013, I contributed to a book titled The Prisoners’ Diaries: Palestinian Voices from the Israeli Gulag, which was published in six different languages. The reaction the book received and the fact that it was available in other languages made me more determined to continue telling the stories of Palestinian political prisoners.

In 2016, I contributed to another book titled Dreaming of Freedom: Palestinian Child Prisoners Speak, which was also published in Arabic. I was able to tell the story of child prisoner Ayman Abbasi who, after his release in September 2015, was shot dead in Jerusalem by Israeli border guards while participating in a protest against Israeli punitive measures in Jerusalem such as house demolitions.

Connecting struggles around the world

This year, I contributed to a new book which came out in July and which narrates the stories of Palestinian and Irish hunger strikers. Published by the Belfast-based An Fhuiseog, A Shared Struggle— Stories of Palestinian & Irish Hunger Strikers contains the stories of 31 Palestinian and Irish hunger strikers who went on hunger strike individually and collectively in Israeli and British jails.

Working on the book has once again made me feel the power of connecting the personal stories of Palestinian prisoners with other struggles. Palestinian journalists Moath Alamoudi and Fayha Shalash interviewed the Palestinian prisoners, and Danny Morrison and Asad Abushark edited the book, which was supervised by Norma Hashim, providing an example of the intersectionality of the Palestinian cause and the international solidarity with it.

My journey to journalism is similar to that of other Palestinian journalists who, too, have felt compelled to become journalists to share the stories of their people and highlight issues that the mainstream international media will not otherwise adequately cover. I spoke to a number of Palestinian journalists about how their personal experiences led them to journalism and how they remain objective while essentially under fire themselves.

Issam Rimawi

Issam Rimawi, a photojournalist from the West Bank city of Ramallah, noted that when Israeli forces invaded his town of Beit Rima in the West Bank in 2001, there were no cameras or smartphones to document the invasion.

“They committed a massacre against our people and there was no documentation of it. This incident has greatly influenced my choice of journalism as my department at university and later as my career. It is because of this incident that I insisted on studying journalism and I received much support from the people of my town and my own family.”

Rimawi says that separating reporting on the occupation from being Palestinian is not possible.

“You are not from Hong Kong coming here to report and leave. You are Palestinian after all, covering the killing, shooting, arrest and injury of your people. These are your own people and your town.”

He adds that, despite this, as a journalist, one should not “intervene in the course of events so as not to give the Israeli occupation the justification to make you part of these events”. Rimawi adds that it is necessary to report events and news as they are without faking them and by committing to the truth.

“The photo is important, but your personal safety is more important,” he concludes.

Linda Shalash

The journey into journalism for Palestinian journalist Linda Shalash from Ramallah, who worked as a reporter for a local TV station but is now based in Istanbul, was similar to that of Rimawi. Shalash told Al Jazeera Journalism Review that at the age of 13, when the Second Palestinian Intifada broke out in 2000, “the idea of journalism got into my mind.

“I was especially impacted by the news coverage of Palestinian journalists during the events of the Intifada, including Laila Odeh, who worked as a reporter for Abu Dhabi TV in the past.”

For Shalash, Odeh had courage and was brave, and “I wanted to become like her and convey the plight of the Palestinian people under occupation”. Shalash explains that, at first, her family did not want her to join the journalism department at university, because her GPA was 97 percent. They felt she should study business or translation because working as a journalist is perceived as a dangerous job. “I stuck to my passion and studied journalism,” she says.

On the issue of neutrality, Shalash believes that as a Palestinian journalist, she can’t be neutral. “But I do my best to be objective, and it is not easy.”

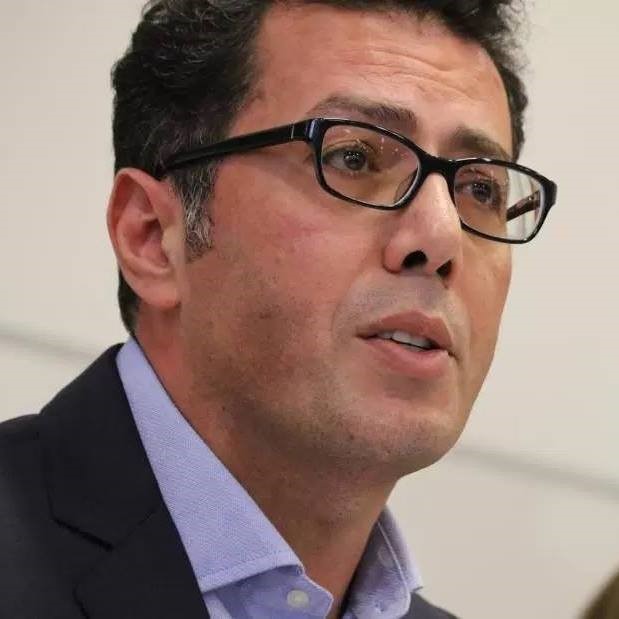

Ramzy Baroud

Palestinian journalist, columnist and author Ramzy Baroud who edits the Palestine Chronicle, recalls how his personal experiences under Israeli occupation have shaped him as a journalist, adding that: “They served as my main motivation to become a journalist in the first place.”

Baroud recalls growing up in a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip, where the daily routine included “desperate attempts at survival and battling with Israeli army soldiers who invaded our refugee camp, Al-Nuseirat. Adjacent to my house was the Martyrs’ Graveyard, which seemed to be in constant expansion as a result of the killing of Palestinians at the hands of the Israeli occupation. Many of those victims were family members, close friends and neighbours.”

On the subject of neutrality, Baroud asserts that “neutrality and objectivity are either fraudulent or impractical, convenient concepts that were coined by Western media and academia to prevent the colonized and oppressed from communicating their story to the rest of the world with feelings and emotions. In journalism, as well as in any other field of reporting or research, there is still a right and a wrong, a justice and an injustice, an oppressed and an oppressor.

“That said, one must remain committed to accuracy and integrity in reporting so as not to allow one’s beliefs, ideas, and emotions to alter or, worse, fabricate facts. Doing so does much harm to the integrity of the journalist, and more importantly, to the struggle of oppressed people. While I refuse to commit to fake ‘neutrality’, I remain committed to the truth, however painful and uncomfortable it may be,” he concludes.

Many Palestinian journalists have been shaped by the collective experiences of their people under Israeli occupation which pushed them to “become” or “made them journalists”, he adds.

Jehan Alfarra

From her London office, Palestinian digital journalist Jehan Alfarra, who grew up in Gaza, aims to amplify Palestinian voices through her work. Through her reporting and video-editing, she highlights the situation back home. Her shift from architecture to journalism was shaped by her own experience in Gaza especially after Israel launched the Cast Lead Operation in 2008-2009.

“Growing up, I often dreamt of becoming an interior designer,” she says. “After I graduated from high school in 2008, I started studying architecture for my undergraduate degree. That did not last long. Israel launched Operation Cast Lead on December 27, 2008, on the first day of my final exams.

“By the end of the assault, the laboratories I regularly used during my studies at university were destroyed, and during that time I found myself writing about Cast Lead and what I was witnessing in Gaza. I felt a deep urge to report what was happening to the outside world. This pushed me to change my major and start working as a journalist even as a student,” she tells Al Jazeera Journalism Review.

As a high-school exchange student in the US, Alfarra says she was exposed to the bias of the US media towards Palestine. “The reporting I witnessed was extremely one-sided and lacking. The Palestinian narrative was, when not misrepresented, almost non-existent.”

On the issue of remaining “neutral” as a Palestinian journalist, Alfarra adds that it is often said that the detachment of war correspondents makes them better journalists, and able to remain objective and neutral.

“But sometimes it is impossible for foreign journalists to capture the truth of a situation. Many times, I've worked with international journalists who are normally stationed in Israel or Jerusalem and only enter Gaza during or after specific events. They lack true context. They do not have a full understanding of the situation. Other times they already have their own views or are sympathetic to a single narrative that they push. Neutrality then is very superficial.”

Alfarra concludes by saying that: “It is a journalist’s moral duty to tell the truth of what they witness. As long as you present the facts on the ground and what you witness, whether or not you agree with it, then your voice as a journalist ought to be heard.”

In the context of Palestine, many Palestinians who think that mainstream media outlets, especially those in the US and Europe, do not report their plight in a fair manner, feel it is now their duty to become journalists and do the job themselves.

For these reporters, being objective does not always mean being neutral, because, as Rimawi says, “you are a Palestinian after all”. Journalism in the context of Palestine has become more than just a career and it is very much shaped by personal stories and experiences.