This article was originally written in Arabic and translated into English

Where does compassion end and journalism begin? How can one engage with children ethically, and is it even morally acceptable to conduct interviews with them? Palestinian journalist Reem Al-Qatawy offers a profoundly different approach to human-interest reporting. At the Hope Institute in Gaza, she met children enduring the harrowing aftermath of losing their families. Her experience was marked by intense professional and ethical challenges.

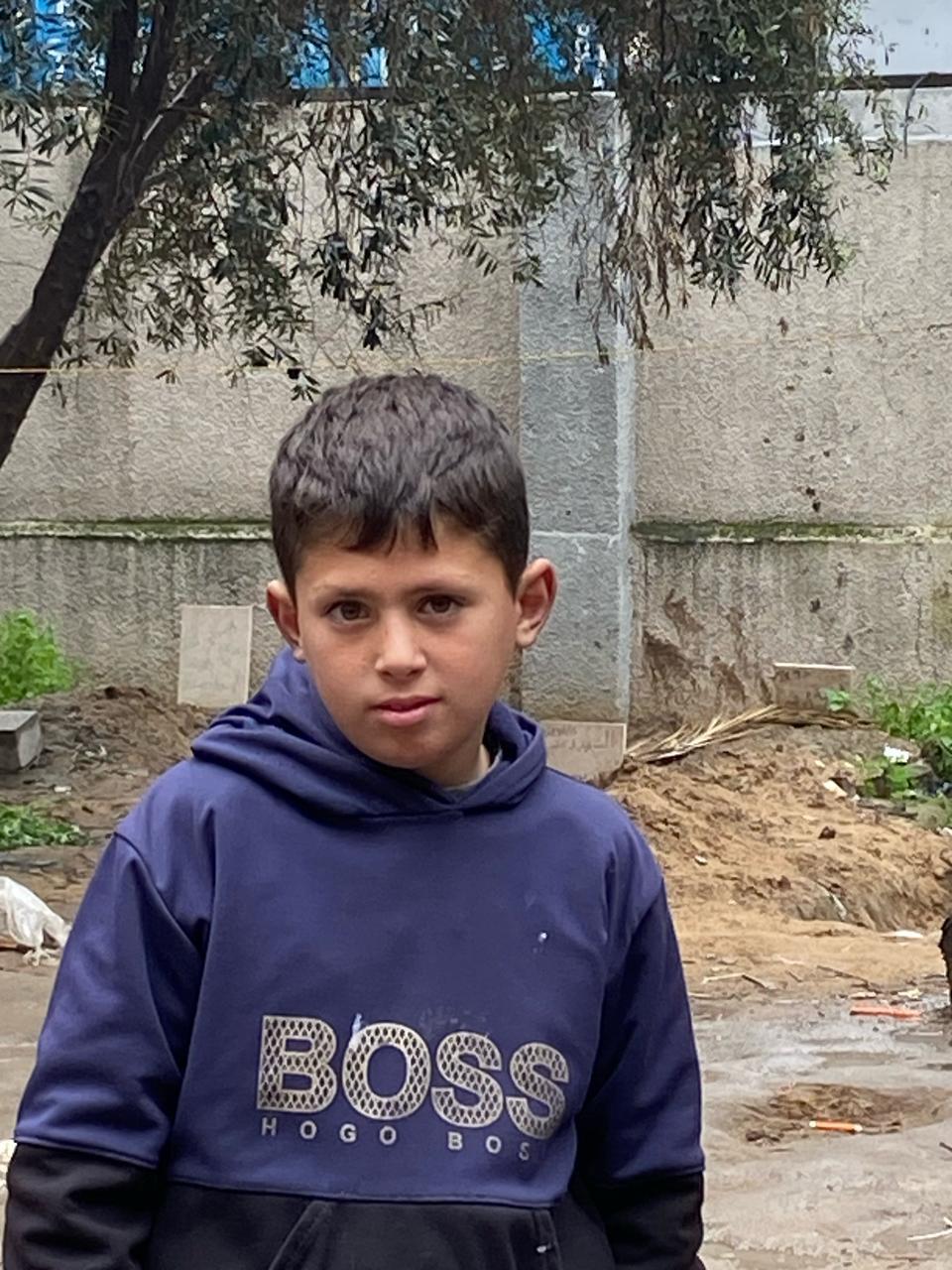

When I sat across from Youssef, Youssef Amer Jondia, the sole survivor of his family who perished in the massacre of October 13, 2023, at the Hope Institute in Gaza, I felt I was in front of a child who had not yet emerged from the spiral of trauma: lost eyes and a faint voice, as though recounting chapters of pain without fully grasping the magnitude of the catastrophe that had swept over his small head. I knew I was facing a deeply sensitive moment, one that could not be reduced to a mere journalistic interview with a young boy still reeling from trauma. With every question I tried to ask Youssef, I attempted not to touch his pain or deepen his sorrow, while fear constantly shadowed me, fear of overstepping the limits of what he could bear. Every part of the interview was a psychological challenge for me: How could I give him space to express himself without pressuring him? How could I balance my role as a journalist with my desire to protect him from the wounds that had yet to heal? And was it even ethical to conduct the interview in the first place? The truth is, it wasn’t just a series of questions and answers; it was a continuous internal struggle between professionalism and emotion.

A Delicate Balance

38,000 orphans and 14,000 widows now face a fate shrouded in uncertainty following the successive crimes committed by the Israeli occupation since October 7, 2023, in the Gaza Strip. These were not just numbers, but stories that compelled me, as an independent journalist, to document them, especially at the Hope Institute in Gaza.

This conviction pushed me to write, not merely out of professional duty, but as a moral and human commitment, because their stories deserve to be preserved. Every time I sat with a child who had lost their parents, I recalled the words of the martyred Dr. Refaat Al-Areer: “If I must die, then you must live to tell my story.”

Today, in Gaza, we carry the responsibility of conveying this trust. We are its generation, its witnesses, and its victims. We narrate to the world the stories of these children so their voices may remain a testament to the truth and to the resilience of a people whose spirit has not been broken, despite everything.

Journalism, at its core, is not merely a tool for relaying events but a means to restore dignity to victims, to document pain and hope together in a world crowded with news yet often blind to the human dimension of events. In this context, human-interest storytelling emerges as one of the most vital forms of journalism, enabling us to move beyond traditional reporting through deep narrative that allows readers to understand reality more comprehensively.

My experience covering children’s stories at the Hope Institute for Orphans was rich with knowledge and with challenges. It required a precise balance between journalistic credibility and adherence to the ethical standards of humanitarian journalism.

On a human level, working with children demanded special sensitivity; they are not merely sources but souls bearing stories worthy of being told with dignity and respect. Thus, it was imperative to build a relationship based on trust, while ensuring their protection from any psychological harm that might arise from interviews or storytelling.

I realized that a journalist intersects with the pain of their people and lives its details. Therefore, it is essential to present compelling yet objective narratives without falling into the trap of emotional sensationalism or unethical exploitation of the elements of the stories they cover. Journalistic responsibility mandates presenting a realistic picture without exaggeration, while adhering to standards of integrity and accuracy.

On a human level, working with children demanded special sensitivity; they are not merely sources but souls bearing stories worthy of being told with dignity and respect. Thus, it was imperative to build a relationship based on trust, while ensuring their protection from any psychological harm that might arise from interviews or storytelling.

It wasn’t easy, I faced psychological challenges too. Some stories required time to process before I could write about them. My goal was not merely to highlight their suffering, but to offer them the opportunity to be the true narrators of their own experiences, conveying their dreams, fears, and life details that reflect human dimensions beyond mere names and pictures.

The power of the human-interest story lies in its ability to create social awareness around the issues of orphaned children. It does more than present information, it places the reader at the heart of the event, enhancing their understanding and empathy toward the characters in the story. The journalistic story is not merely a reflection of reality, but a bridge between those living the suffering and those reading about it, so that they may feel it, comprehend it, and perhaps act upon it.

This experience was more than an addition to my professional résumé; it changed my outlook on life. I learned that journalism is not just about reporting events but a means to understand the human being behind the news. I saw in the eyes of children a passion for life despite the harsh conditions, and I realized that every child has a story worth telling in a way that respects its details and reflects its truth.

This experience was more than an addition to my professional résumé; it changed my outlook on life. I learned that journalism is not just about reporting events but a means to understand the human being behind the news. I saw in the eyes of children a passion for life despite the harsh conditions, and I realized that every child has a story worth telling in a way that respects its details and reflects its truth.

Human Stories

My coverage did not stop at highlighting children’s suffering but also shed light on their dreams and aspirations, especially in the field of education amid Gaza’s current situation. Education at the institute focuses on the secondary school level (Tawjihi) due to its particular importance in students’ lives. Yet the students face great challenges: a lack of basics such as chairs, classrooms, and stationery; limited space; paper shortages; and the high cost of printing, along with the absence of a consistent academic calendar. Despite these obstacles, the students insist on attending daily, carrying their chairs from distant places to continue their education.

I always remember the words of educator Salwa Hallas, who inspired me with the phrase: “There is nothing harder than raising a girl for ten years, then suddenly she and her siblings are martyred. That alone makes you more compassionate with children and mindful of every word before speaking to them.” These words were a powerful reminder of the importance of care in language when dealing with children.

One of those who left a deep mark on me was a 16-year-old girl who lost her entire family in the war and became the sole survivor. Despite severe injuries, she memorized the entire Qur’an during that time. The institute adopted her case, assigning a psychologist to help her overcome her ordeal and provide a supportive and educational environment, academically and emotionally. She is a model of resilience; education became her tool for survival and recovery amid the brutal conditions she endured.

During my field coverage of this humanitarian catastrophe, I felt the weight of a responsibility I could not ignore as an independent journalist. Meeting Youssef Amer Jondia, the sole survivor of his family who perished in the massacre of October 13, 2023, was a moment I will never forget. Eleven-year-old Youssef lost his father, mother, and five sisters in that horrific instant. Since the beginning of the war, he has been living at the institute. Now, after a long treatment journey at Al-Shifa Hospital, he is trying to reclaim a piece of his lost normalcy and resume his studies.

I never lost sight of the role education plays in Youssef’s life, despite his suffering. I asked the institute’s administration how he was managing to continue his education under such psychological strain. They told me the institute provides educational tents for displaced children, and that Youssef is deeply committed, he doesn’t miss a single class. His dedication to learning is a message of hope amid devastation.

Before every journalistic piece, I find myself in deep perplexity: How can I describe the indescribable? How can I say the unsayable about children who have lost everything? This places me in a constant internal struggle between professionalism and emotion, and challenges the limits of language in capturing a reality that transcends words.

During my conversation with Youssef, I gently asked:

“If there’s one thing you wish could go back to how it was before the war, what would it be?”

A long silence followed. Youssef looked away and then answered:

“To have Dad, Mom, and all my sisters back…”

He paused, took a deep breath, and added:

“…and school to come back.”

Then he looked at me again:

“…I want to become like Dad, a doctor.”

Today, Dar Al-Arqam School sponsors Youssef’s education, while the institute oversees his psychological condition and provides full care through counseling and psychological support programs. Despite all the pain, there remains hope and great dreams for a child who has yet to overcome the shock of loss but is steadfastly trying to recover a part of the life he once had.

At the same institute where Youssef receives care and support, there is Islam Atef Jondia, 25, a widow and mother of three. She moved there after losing her husband and his father in a missile attack on Harazin, Shujaiya. Islam recounts:

“I was in the Harazin area of Shujaiya when we were hit by successive missiles. My husband and his father were with us, and they were martyred instantly in those horrific moments. After that ordeal, I moved with my children to the Hope Institute for Orphans on February 17, 2024. But even in the institute, we weren’t safe, parts of the institute buildings were bombed while we were there, adding to the hardship we were already facing.”

I asked her: What challenges do you face in your husband’s absence? How do you provide a safe environment for your children?

Islam replied: “Everything is hard. Nothing can replace a father’s presence. My children often ask me, especially my three-year-old daughter and my six-year-old twins, ‘Mama, where’s Daddy?’ I tell them: ‘Daddy is in heaven.’ It’s a heavy burden, which is why I decided to complete my secondary education (Tawjihi) at the institute, so I can create a better life for my kids.”

I asked her: Do you think you’ll be able to overcome this phase?

Islam answered: “Yes, I must overcome it. There is no third option. Electricity is not always available, plus the responsibilities of raising children. The burden is heavy, but I’ll keep trying because education for a girl is power.”

Before every journalistic piece, I find myself in deep perplexity: How can I describe the indescribable? How can I say the unsayable about children who have lost everything? This places me in a constant internal struggle between professionalism and emotion, and challenges the limits of language in capturing a reality that transcends words.

Covering human-interest stories of orphaned children at the Hope Institute in Gaza was not just a professional experience, it was a human journey that enriched my understanding of journalism’s role in serving community causes.