In Chiapas, independent journalists risk their lives to document resistance, preserve Indigenous memory, and challenge state and cartel violence. From Zapatista films to grassroots radio, media becomes a weapon for dignity, truth, and survival.

“The possibility of creating independent media is fundamental,” said Paco Vasquez, a journalist and activist from Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state.

Mexico is not only one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist; it also has “one of the highest media concentrations”, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF). This means that a small number of companies control a large share of media outlets, which “limits the pluralism of the information available to the public and drives more and more independent journalists to post their work on social media.”

But the sustainable development of independent, citizen-led journalism requires training and support.

Since 1998, this has been the guiding principle at ProMedios de Comunicación Comunitaria, a citizen journalism project focused on community development, human rights, and the democratisation of media. Based in San Cristobal de la Casas, Chiapas, it was founded in response to a revolutionary insurgency four years prior, when an estimated 3,000 Indigenous men and women declared war on the Mexican State:

“We are the product of 500 years of struggle,” proclaimed the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) on 1 January 1994. Donning black balaclavas and red bandanas, armed with machetes and old rifles, they seized seven municipalities from the hands of the governing elite: “Today we say enough is enough (¡ya basta!).”

The First Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, one of six communiqués issued by the EZLN between 1994 and 2005, first appeared in the Chiapas-based newspaper Tiempo. Shortly after, an interview with Zapatista commanders in the Mexican newspaper La Jornada provided some of the earliest first-hand testimonies of Zapatismo in the national press.

But “it was Alexandra Halkin, an American filmmaker, who proposed bringing cameras to various people and initiating a training programme in the use of audiovisual media for the Zapatista communities,” explained Vasquez. The objective was not to make decisions on their behalf but to provide them with the tools to make those decisions themselves.

Filming Resistance: How Zapatistas Document Their Struggle

One film, The Silence of the Zapatistas (date unknown), shows a group of young guerrillas opposing road-building efforts and military blockades aimed at “corralling the Zapatista leadership”. In one scene, a young man confronts a stunned soldier, pleading, “Man, don’t do this. Come to take care of the country, but take care of it; don’t keep destroying it, arsehole.”

“I think that from now on we are going to record many things,” said another Chiapaneco in a film from 1999, “so that we keep a testimony of what is happening.” As he speaks, the camera cuts to footage of deforestation, an ongoing assault that wiped out more than 45,000 hectares of Chiapas’ natural forest in 2024.

Opposing their oppressor was revolutionary in and of itself, but the diligence with which they recorded it, utilising the newly emerging internet to spread their message, ensured their place in the history of resistance.

Radio was another vital method of communication. Established in late 1994, Radio Insurgente provided updates on Zapatista activities, reports on state-sponsored violence, and interviews with commanders. It was dismantled in 2005 following the creation of the Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ) and the Good Government Juntas (JBGs), with control transferred to the newly established localities. As a result, they announced, “The Zapatista civilian population will decide, according to its own time and means, the content of local radio programmes.”

This continued until 2023, when the Zapatistas discarded the organisational structure of the MAREZ and the JBGs.

Today, the radio stations are largely defunct. However, their website, Enlace Zapatista, remains a rich and comprehensive archive of repression and resistance, housing radio broadcasts, communiqués, and news reports from 1994 to the present.

Zapatista Media and the Struggle for a “A More Dignified World”

Since parting ways with ProMedios in 2015, the Zapatistas have continued to harness audiovisual skills to create and control their own media. This includes reports on issues beyond their midst, from condemning human rights abuses in Jalisco, a state in western Mexico, to denouncing the genocide in Palestine some seven thousand miles away.

But solidarity is reciprocal. “Continuing to report on the existence of Zapatismo and other struggles allows us to transcend information and introduce new generations to new possibilities for building a more dignified world,” said Montserrat Rojas and Luis Suaste, journalists from Regeneración Radio in Mexico City.

Founded during the 1999 student movement against rising tuition fees, Regeneración Radio is an independent news outlet based at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Similarly, ProMedios continues to offer young people, primarily from working-class and predominantly Indigenous communities, audiovisual equipment and training to report on armed conflict, grassroots resistance and territorial defence. Amid the worsening human rights crisis in Chiapas, one described as “a spiral of armed and criminal violence”, these opportunities are essential.

But the training goes beyond teaching technical skills. “It’s also about reflecting on the role of communication in society,” explained Paco Vasquez, “and recognising the responsibility to seek out alternative media models that don’t replicate the dominant dynamics of commercial media.”

The Deadly Cost of Independent Journalism in Mexico

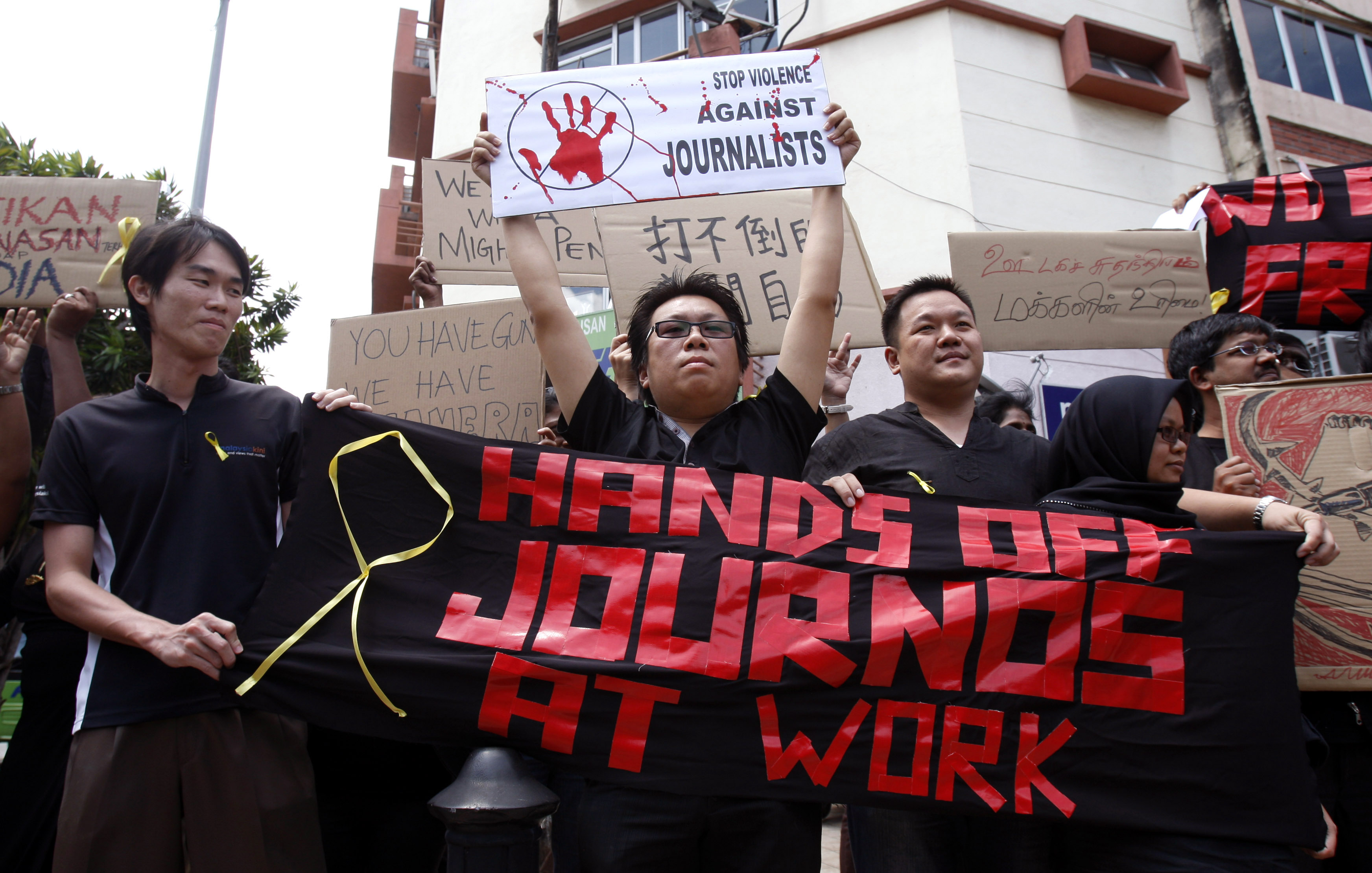

However, in a context “where organised crime and political interests foster an environment of fear and violence”, challenging these dynamics is a tireless endeavour. In fact, of the nine journalists killed so far in 2025, eight were independent. Most worked through Facebook, reporting on local politics, culture, crime and corruption.

Ronald Paz, the most recent victim, administered the Facebook news page NotiExpress Paz Pedro. He was shot immediately after broadcasting a live report in which he identified himself and stated:“We publish all the news that is censored.”

The most recent recorded killing of a journalist in Chiapas was the case of Victor Alfonso Culbero Morales, an Indigenous journalist and director of the independent news portal Realidades.

Morales, originally from San Cristobal de las Casas, was found dead on a roadside with bullet wounds to the head on 28 June 2024. The attack occurred two days after Realidades reported the deployment of 31,000 soldiers in Chiapas in response to rising cartel activity, describing the region as “the scene of the dispute between cartels seeking control of the territory”.

Mexico ranked 8th in the Committee to Protect Journalists’ (CPJ) 2024 impunity index. And despite President Claudia Sheinbaum’s pledge to “protect and defend journalism”, reporters remain under threat.

Yet they continue their work.

“Given the current situation in Mexico and around the world, we believe it is important to exercise the right to communication by supporting and contributing to struggles that resist and organise to confront systemic inequalities and violence,” said Rojas and Suaste.

“We know the risks our work entails; however, we cannot afford to remain silent.”

Preserving Collective Memory Through Grassroots Media Archives

Failing to protect journalists as they document the present endangers our memory of the past.

At ProMedios, alongside its work training citizen reporters, the effort to preserve historical memory led to the creation of the Center for the Preservation of Community Audiovisual Archives (CEPAAC). Housing over 1400 analogue videos, CEPACC represents “over two decades of Indigenous peoples’ struggle to achieve autonomy and dignity in the face of overwhelming obstacles,” said Paco Vasquez.

Naturally, many of these materials reference the Zapatistas, used “to engage in dialogue with contemporary generations who are seeking to understand their current context”.

In 2015, a similar initiative was taken up by library and archive experts at UNAM. They uncovered 47 years of coverage by Tiempo, the Chiapas-based newspaper that published some of the earliest reports on the Zapatista uprising.

“The rescue work, which began in 2012, consisted of classifying, processing, and binding copies of these newspapers so that their historical content would be accessible to researchers, students, and the general public,” according to the independent outlet, Chiapas Paralelo.

For Vasquez, the objective of this process is clear: to preserve a history that, “if not rescued soon, will leave a void in the collective memory, leaving only private and state institutions with the resources to tell the audiovisual history of this region.”