Corporate influence in Indian media has led to widespread editorial suppression, with media owners prioritising political appeasement over journalistic integrity, resulting in a significant erosion of press freedom and diversity in news reporting.

In September 2021, when Ruben Banerjee, the then Editor-in-Chief of Outlook Magazine, proposed a contentious cover story critical of the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, ruled by Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), he was immediately sacked. The story, which was intended to scrutinise the communal rhetoric of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, allegedly drew disapproval from the magazine's management, who were wary of political repercussions.

I actually lost my Outlook job because of my cover story against the Modi government. The moment I did that cover, it became a talking point across India. Immediately, the very same day, my owners told me that we cannot anymore do such stories.

Like many other media houses in the country, Outlook magazine, owned by a corporate house—the Rajan Raheja Group—is a diversified conglomerate with interests in real estate, cement, and financial services and doesn’t want to be at loggerheads with the government.

Banerjee’s removal was not one-off but is rather part of a broader trend of editorial suppression in India, where media owners often prioritise political appeasement over journalistic integrity, especially when confronted with stories that critique powerful figures.

“I actually lost my Outlook job because of my cover story against the Modi government,” Banerjee told Al Jazeera Journalism Review, referring to a cover story critical of the Indian Prime Minister’s handling of the Covid pandemic, which he had commissioned two months before being sacked.

“The moment I did that cover, it became a talking point across India. Immediately, the very same day, my owners told me that we cannot anymore do such stories.”

Corporate Takeover

India’s media landscape is increasingly dominated by corporate ownership, with business tycoons like Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani, both considered close to the ruling BJP, acquiring stakes in prominent news outlets.

As of 2019, Ambani owned 72 TV channels in the country. Adani, on the other hand, in the last couple of years has taken over two media outlets—NDTV and Quint—which were considered the last bastions of critical reporting against the government. In December 2022, then the world's third richest man, Adani, took near-total control of NDTV and then expanded his media influence by acquiring the Quint.

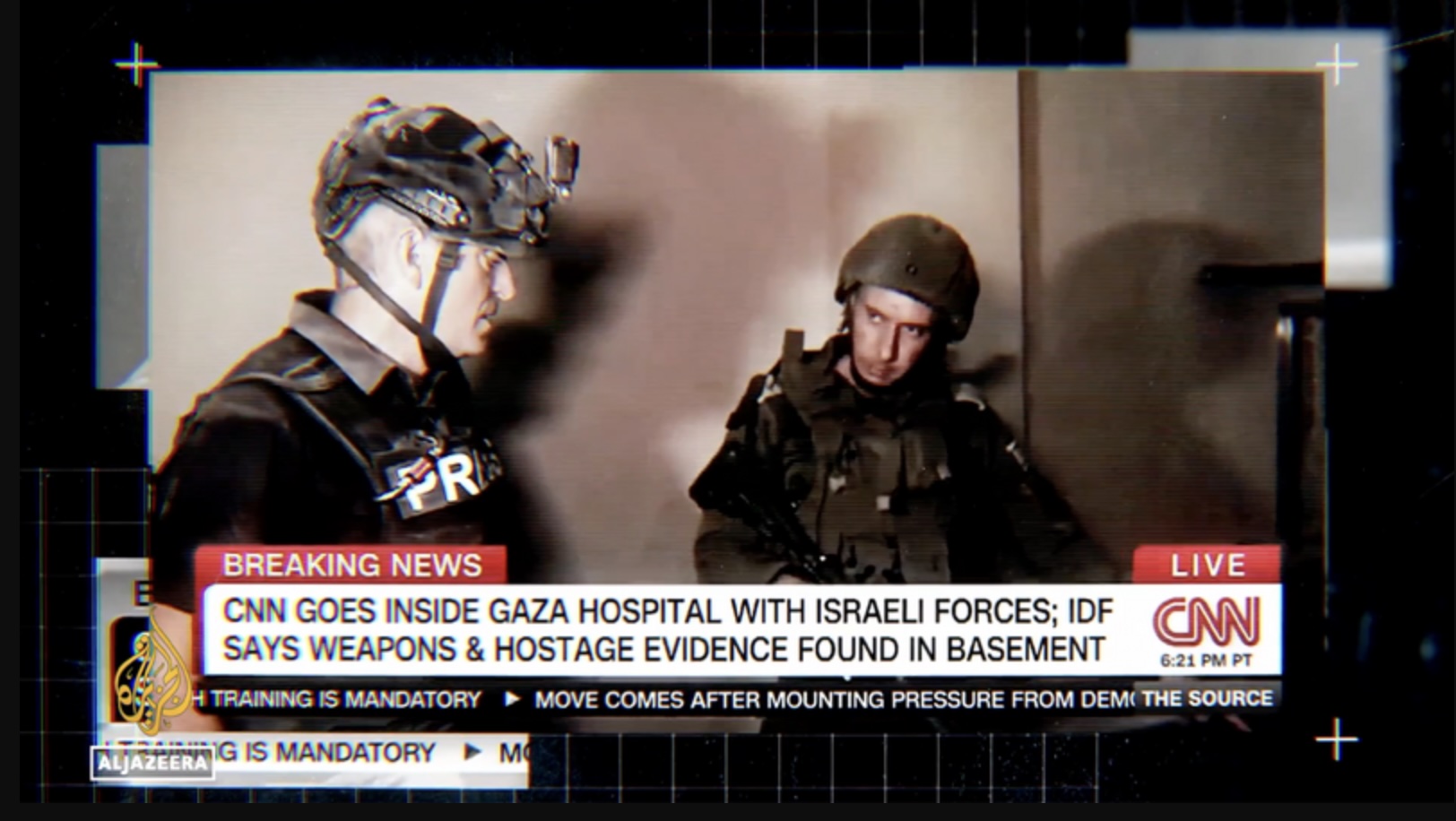

If, for instance, a news story surfaces that clashes with the interests of Gautam Adani—such as a Swiss court ruling against entities linked to his group—you won’t come across it on NDTV, which falls under the Adani umbrella. Instead, the news dissolves into silence.

This corporate consolidation has raised concerns about media independence in the country. Experts say the blurring lines between business and media ownership in India have threatened press freedom, reduced diversity in news reporting, and undermined democracy by controlling the narratives accessible to the public.

“If, for instance, a news story surfaces that clashes with the interests of Gautam Adani—such as a Swiss court ruling against entities linked to his group—you won’t come across it on NDTV, which falls under the Adani umbrella. Instead, the news dissolves into silence,” said Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, a veteran journalist based in New Delhi and writer of the book Sue the Messenger.

Historically, corporate influence has always been present in the country’s media industry, starting with the jute barons controlling big newspapers post-independence in 1947. "However, a metaphorical ‘Chinese wall’ traditionally separated editorial independence from business interests. Over the years, that wall has been broken down,” Banerjee told Al Jazeera Journalism review, pointing out that the editorial decisions are now dictated by corporate bosses rather than editorial leads.

This erosion of the editorial-management divide, as per Banerjee, has resulted in editorial teams becoming subservient to marketing and advertisement departments, where stories are often aligned with corporate and political interests.

“Generally speaking, barring a few exceptions, the editors in India dance to the tune of their owners and the marketing and advertisement bosses,” Banerjee said.

Compromised Journalism

Corporate influence on editorial decisions is not confined to national media or specific political affiliations. Banerjee explains that the issue extends to state-level media across India, irrespective of the ruling party. Whether in BJP-led states or those governed by opposition parties, local media outlets capitulate to the whims of the powerful.

“But it is happening in all the states, irrespective of who is in power. The misconception is that it is only the ruling BJP which is doing this. Whichever party is in power in the state, they are calling the shots, and the local media is capitulating to them,” he added.

Banerjee’s experience is not unique. Khalid Ahmed (name changed), a young reporter who worked for Network 18 till last year, a media conglomerate owned by Ambani, said that criticism of corporate owners or their companies is off-limits in the newsroom. “Show me one investigative piece done by any Indian mainstream newsroom in last 5 years against any of these corporate highbrows?” Ahmed said, adding that “not only owners but their friends and other corporate houses who pay for advertisements cannot be touched.”

Ahmed left the newsroom in 2023.

"Editors there (Network 18) didn’t allow any critical reportage on frauds committed by these corporate houses because, immediately, the PR guy would come and shout that they would cut the funds," he explained. "Only if a court has passed some directive against them, then you may write," Ahmed added, pointing to the limited circumstances under which critical stories are permitted.

Show me one investigative piece done by any Indian mainstream newsroom in last 5 years against any of these corporate highbrows? Not only owners but their friends and other corporate houses who pay for advertisements cannot be touched.

The situation isn’t different in another newsroom Ahmed joined after leaving Network 18. “There is the same kind of censorship, if not worse. You cannot write anything against the top ruling leadership of the country or corporations that fund them,” he said.

“It is an unwritten rule. You cannot write anything against [ Prime Minister] Modi or [Home Minister] Amit Shah or conglomerates like Reliance or Patanjali, he added. Reliance Industries is owned by Mukesh Ambani, and Patanjali Ayurved is an Indian multinational conglomerate holding company founded by Ram Kisan Yadav, more famously known as Baba Ramdev, a yoga guru considered very close to the government.

No Editorial Independence

Ahmed believes that this pan-Indian infiltration of corporate and political influence has created a chilling effect on journalism, with far-reaching consequences for media pluralism, public trust, and democratic discourse. “In our newsrooms, dissenting voices are marginalised, and critical stories are sidelined.”

There were multiple instances where I had to change the headlines, the lead, and the main image of the story to protect corporate interests. The corporate influence was so pervasive that editorial independence only existed for inconsequential news

Ahmed now plans to leave journalism altogether and is looking for job opportunities in other fields.

Mahesh Anand, 27, (name changed), a former subeditor at the same organisation, said the lack of editorial independence became immediately apparent upon him joining the newsroom. “There were multiple instances where I had to change the headlines, the lead, and the main image of the story to protect corporate interests,” Anand revealed.

“The corporate influence was so pervasive that editorial independence only existed for inconsequential news,” Anand said.

Anand, like many other young journalists in the country, entered the field driven by passion and a desire to uphold integrity. However, the reality of the job quickly extinguished these ideals. “If you cannot write against the government or the corporations, what exactly is the point?”

Disillusioned, Anand left the mainstream media and has transitioned into a different line of work.

“I didn’t want to be a mouthpiece,” he said.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera Journalism Review’s editorial stance.