When media institutions first envisioned editorial charters and professional codes of conduct, their primary goal was to safeguard freedom of expression. However, experience has shown that these frameworks have often morphed into a "vast prison", one that strips journalists of their ability to confront authority in all its forms. In this way, Big Brother dons velvet gloves to seize what little space remains for the practice of true journalism.

In the course of their journalistic careers, many reporters encounter defining moments, points at which they confront the true nature of their role in shaping news narratives. Do they report events with objectivity, or are they drawn into colouring and directing the story to serve specific agendas? But the more critical question is: does the journalist realise they are engaging in propaganda while writing, or do they adopt it unconsciously? And when asked to show bias, do they have the right to refuse, or must they bury their professional conscience beneath editorial directives and institutional policies?

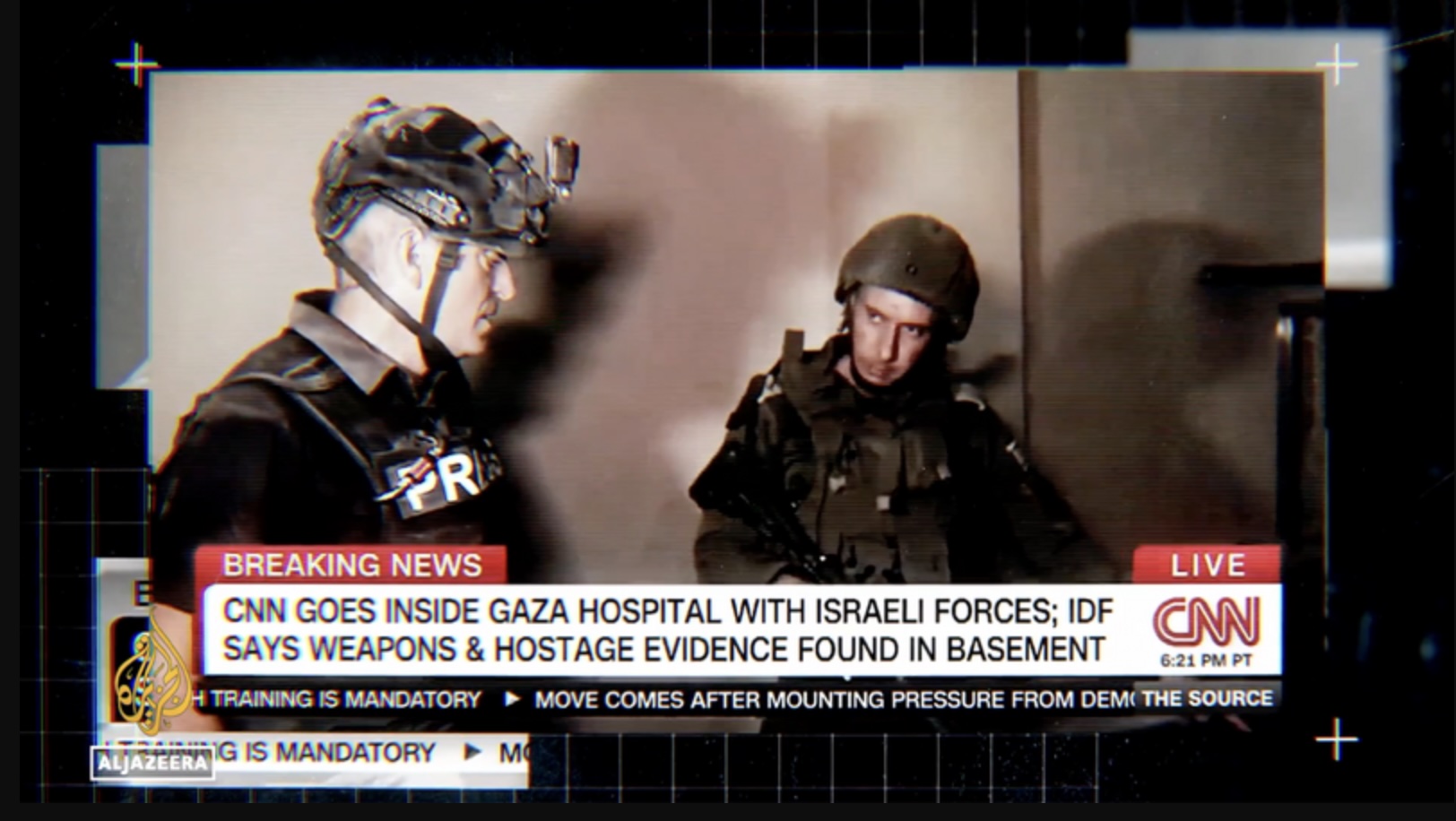

In today’s complex media landscape, “Big Brother” no longer appears in military garb or brandishes towering propaganda posters as envisioned in George Orwell’s 1984. Instead, his presence is subtler, seeping into newsrooms through directed funding and unspoken instructions. Control no longer requires overt repression; it operates by arranging facts, selecting angles, and rewriting headlines to craft an acceptable version of “truth” aligned with the institution’s interests or the boundaries set by those in power.

Between "Guidance" and Conscience

This is the reality that Ahmad, a journalist at an Arab media organisation in Jordan, found himself confronting. He began his career believing he was merely a conduit for events, but after October 7, everything changed. Ahmad realised the compass of coverage had drifted from truth toward alignment with institutional interests and political agendas.

“At first, I edited news reports even when I wasn’t convinced by the content,” he recalls. “But over time, I saw that every story was subject to scrutiny based on its stance on the Palestinian issue. There was clear pressure to reframe the news. This conflict between my professional conscience and the demands of the job made me wonder, 'Am I just a messenger of facts or a mouthpiece parroting what I’m told?'”

In today’s complex media landscape, “Big Brother” no longer appears in military garb or brandishes towering propaganda posters as envisioned in George Orwell’s 1984. Instead, his presence is subtler, seeping into newsrooms through directed funding and unspoken instructions. Control no longer requires overt repression; it operates by arranging facts, selecting angles, and rewriting headlines to craft an acceptable version of “truth” aligned with the institution’s interests or the boundaries set by those in power.

Manar (a pseudonym) faced a more direct confrontation with the system. Her editor-in-chief instructed her to revise a report to align with a specific narrative that contradicted the story’s original context and cast her country in a negative light. Manar refused. Three months later, she succeeded in publishing the piece as she had originally written it.

According to Dr Saddam Al-Mashaqbeh, a professor of media and communication at the Applied Science Private University, a journalist’s awareness of their participation in propaganda depends on their cultural and professional background. Seasoned journalists, he notes, typically possess the discernment to distinguish between professional media work and directed political messaging. They're also generally aware of the ideological stance of the institutions they work for. “That's why many of them choose to join organisations that align with their intellectual and political convictions.”

Dr Ali Shams Al-Zeinat, a professor of journalism and digital media at Yarmouk University, argues that a journalist with a conscious professional ethic rarely becomes a propaganda tool, unless their personal beliefs align with the directed message. Others, however, may be exploited either with their consent or due to personal predispositions. Sometimes, Al-Zeinat explains, journalists become mechanical, processing news content mindlessly, unaware of the messages they’re conveying. “In some cases, they unknowingly create propaganda themselves, passing along or producing content that aligns with ideological motives or personal loyalties, unintentionally distorting the narrative to fit passion rather than fact.”

A Battle in the Newsroom

Mariam did not expect her report to spark a newsroom conflict. She had conducted a thorough investigation into a sensitive student issue at a Jordanian university, relying on direct sources and presenting events as they occurred. But she was abruptly instructed, “We don’t work with this source. Rewrite the piece to implicate the student group.”

This was not a minor edit; it was a deliberate erasure of the truth she had uncovered. It was not merely an editorial decision, but a test of what it means to be a journalist. Mariam chose not to be complicit in the manipulation. She closed the file, apologised to her sources, and withdrew from the story. The report was shelved and erased from the editorial agenda.

At first, I edited news reports even when I wasn’t convinced by the content,” he recalls. “But over time, I saw that every story was subject to scrutiny based on its stance on the Palestinian issue. There was clear pressure to reframe the news. This conflict between my professional conscience and the demands of the job made me wonder: am I just a messenger of facts, or a mouthpiece parroting what I’m told?

Lina’s story offers yet another angle on this internal conflict. Working at an ostensibly independent Arab media outlet, she believed editorial freedom was guaranteed. But she gradually realised that even “independent” institutions are subject to soft steering, control over coverage angles and source selection without direct orders.

Her turning point came after publishing a report on complex political developments in an Arab country. She was met with intense backlash from colleagues, those who often preached journalistic ethics, accusing her of bias. The experience prompted her to reevaluate her place in the organisation.

In a more confrontational case, Lina was told not to use the term “martyrs” when reporting on Palestinian casualties; instead, she was instructed to say “the dead”. For her, that was a red line. She resigned rather than compromise her principles. She realised then that while many journalists surrender to editorial pressures as a matter of course, she could not.

Dr Al-Mashaqbeh explains that media narratives are built within a hierarchy of influence, beginning with the economic system, followed by the political regime, then the media institutions, and finally the journalists. “A journalist may believe they’re exercising true freedom,” he says, “but often they’re reproducing content shaped by what’s been imposed, what we might call 'false consciousness.’”

Al-Zeinat agrees, emphasising that in non-democratic countries, the political system remains the dominant force in crafting media narratives through laws, funding, and both carrot-and-stick strategies. Still, he believes complete control over the narrative is no longer possible. Digital platforms have shifted the paradigm, making ordinary citizens active participants in documenting and shaping events. Nowhere was this clearer than in the coverage of the war on Gaza.

Does the Journalist Kill Their Conscience?

In journalism, professional conscience sometimes feels like a rare currency, gradually eroded by market pressures, political constraints, and financial complexities. The key question is: do journalists truly lose their moral compass, or do they rationalise compromises as a means of survival?

The experiences of many suggest that the slide into propaganda is rarely a conscious choice; it’s a gradual surrender, where options narrow over time.

A journalist with professional conscience rarely becomes a propaganda mouthpiece, unless it stems from their personal convictions. Others are often exploited either willingly or due to their character. Some eventually become machines, processing content without awareness.

A 2021 study by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that journalists in the Middle East face daily encounters with invisible editorial boundaries. Their professional conscience erodes quietly, not in dramatic ruptures, but through subtle, cumulative compromises.

Yet Dr Al-Mashaqbeh stresses that the loss of professional ethics is not inevitable, not even in the most restrictive environments. A journalist may not be able to say everything, but even within narrow margins, they can avoid writing what distorts the truth. “Ethical responsibility starts with the journalist’s awareness that they are not merely messengers of information, but participants in narrative-making. They must constantly ask, "Who benefits from what I write?"

For Al-Zeinat, the media environment, with its legal constraints, economic pressures, and editorial red lines, may affect a journalist’s work, but it does not strip away their conscience if they are committed to journalism’s mission. “A real journalist may retreat tactically, but doesn’t become a propaganda tool. Those who lose their conscience aren’t always victims; they can also be silent partners or skilled justifiers.”

Conclusion: Journalism and the Manufacture of Consent

Media has become a tool for reshaping collective consciousness in a world where it was once meant to be a window to the truth. The issue isn’t just about relaying or falsifying facts; it’s about how the media discourse is controlled through a complex web of political influence, economic leverage, and regulatory frameworks.

What’s most dangerous, Al-Zeinat warns, is not overt content control, but subtle guidance that diverts public attention to marginal issues, amplifies them, and rearranges coverage to serve power’s agenda. Content is presented as the only available truth. In such a system, the unaware journalist becomes a cog, unknowingly complicit in misleading the public and reengineering their understanding.

Today, media no longer impose narratives by force; they construct them with finesse through trust-building and selective revelation or omission. In this reality, a journalist’s vigilance and critical thinking become the final line of defence against the fabrication of false awareness.

Despite the constraints, journalism still holds the power to expose truth for those with the courage to question and the courage to doubt.

References:

-

Cherubini, F., Newman, N., & Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Changing Newsrooms 2021: Hybrid working and improving diversity remain twin challenges for publishers. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Link

Editor’s Note:

The pseudonyms used in this article have been carefully reviewed and verified. An agreement was made with the author to withhold real names to ensure confidentiality.

This article was originally written in Arabic and translated into English using AI tools, followed by editorial revisions to ensure clarity and accuracy