Newsrooms, long lauded as bastions of information, are quietly grappling with a mental health crisis, underscoring an urgent need for systemic support, emotional safety, and sustainable practices to protect those telling the world’s stories.

In newsrooms across the world, the stress of deadlines, increased workload and rise in gruesome content is taking a toll on journalists’ mental well-being.

As a profession, journalism has always been inherently demanding. Journalists are required to be constantly “switched on” and be across all major news and events, whether at work or on a day off.

Generally, the profession offers limited financial returns and almost always puts peace of mind at risk. Long hours, hostile environments and the potential for more adversaries than allies have long been hallmarks of a journalist’s life.

returns and almost always puts peace of mind at risk. Long hours, hostile environments and the potential for more adversaries than allies have long been hallmarks of a journalist’s life.

With falling budgets and rise in competitiveness for share of advertising revenues and clicks, forced layoffs have resulted in smaller teams and overworked staff.

There has also been an increase in the number of conflicts globally. In addition to gory content, news and visuals of death and destruction, the demands of an under-staffed shift and overload of newslines have affected reporters, sub-editors, editors and even interns who want to have a taste of the real working life in the newsroom.

The increased competition among peers, for speed and exclusivity, puts extra pressure to work beyond capacity.

All this profoundly affects journalists’ physical and mental well-being, something that research shows is still a taboo topic and not being discussed and addressed enough.

In India, a young entertainment journalist excited to be part of a new newsroom described the toxicity where expectations spiraled beyond reason and workload that kept them there “24/7”.

A seasoned journalist in Albania experienced workplace challenges that continue to affect her deeply. She said she resigned from her job “due to bullying, toxicity and a really terrible, terrible work environment”.

Journalists Overwhelmed

My recent study published on the state of mental health of journalists and its handling in newsrooms echoed that sentiment and revealed worrying results:

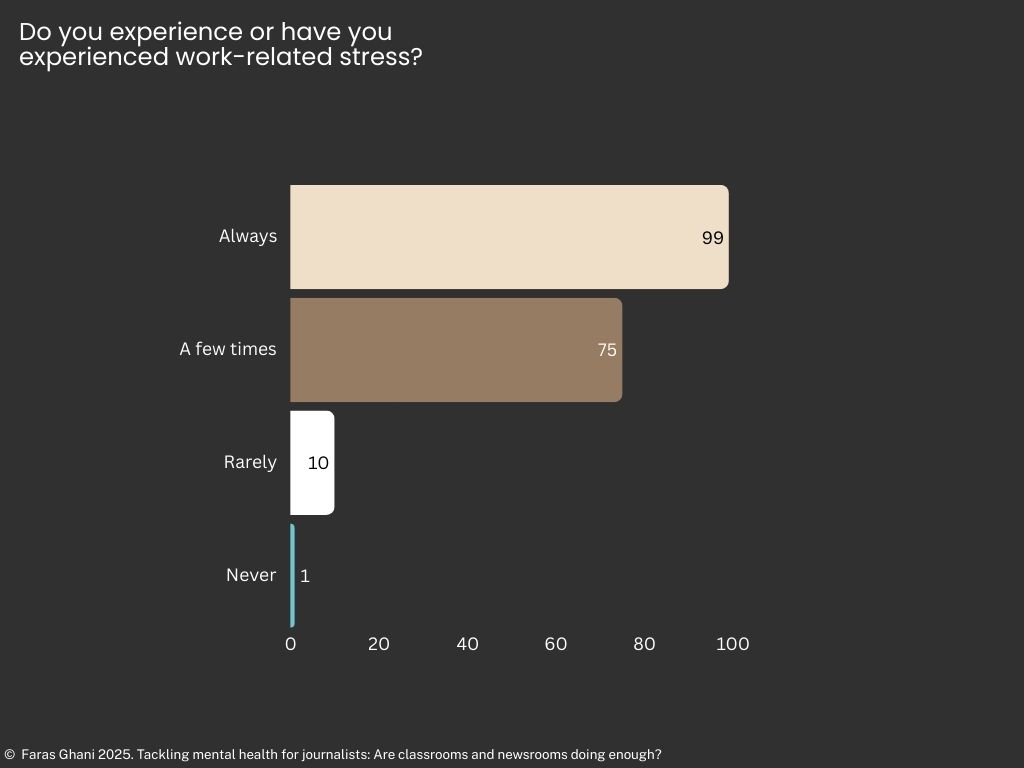

A staggering 93 percent of journalists said they have faced mental health challenges on the job.

A staggering 93 percent of journalists said they have faced mental health challenges on the job.- Over 54 percent are always working under stress.

- Around 66 percent cited workload as one of the many reasons they have experienced stress at work or while working.

- Almost 48 percent work more than they should, with almost a quarter of respondents saying they work more than 50 hours a week.

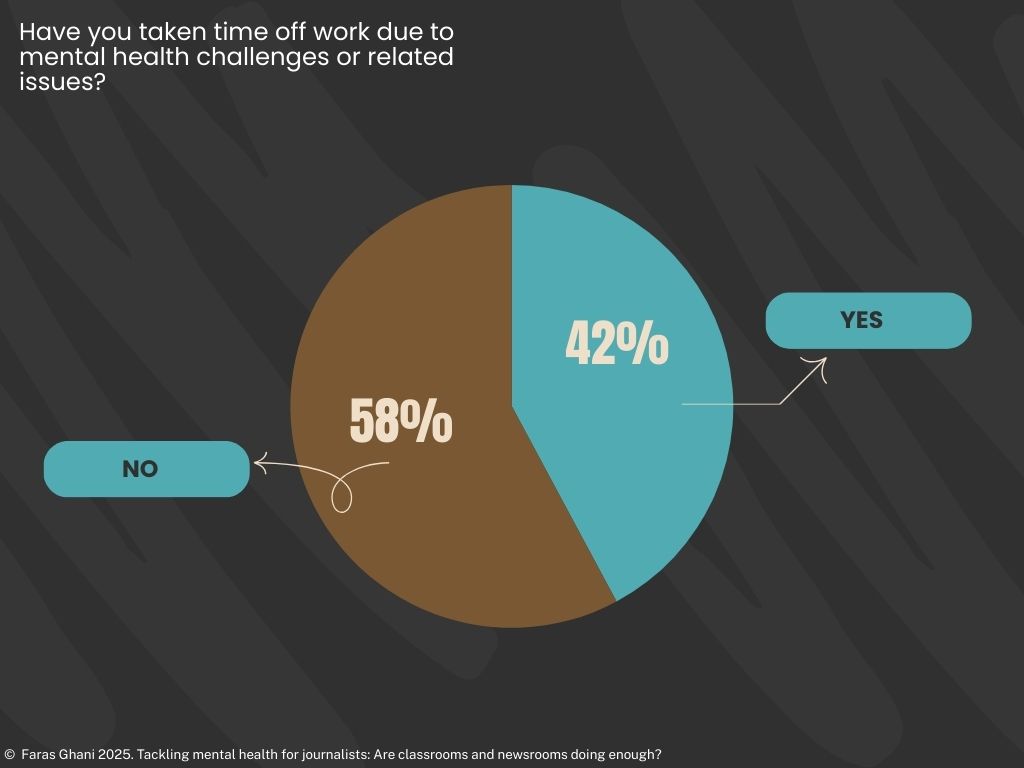

- Some 42 percent had to take time off due to mental health or related challenges.

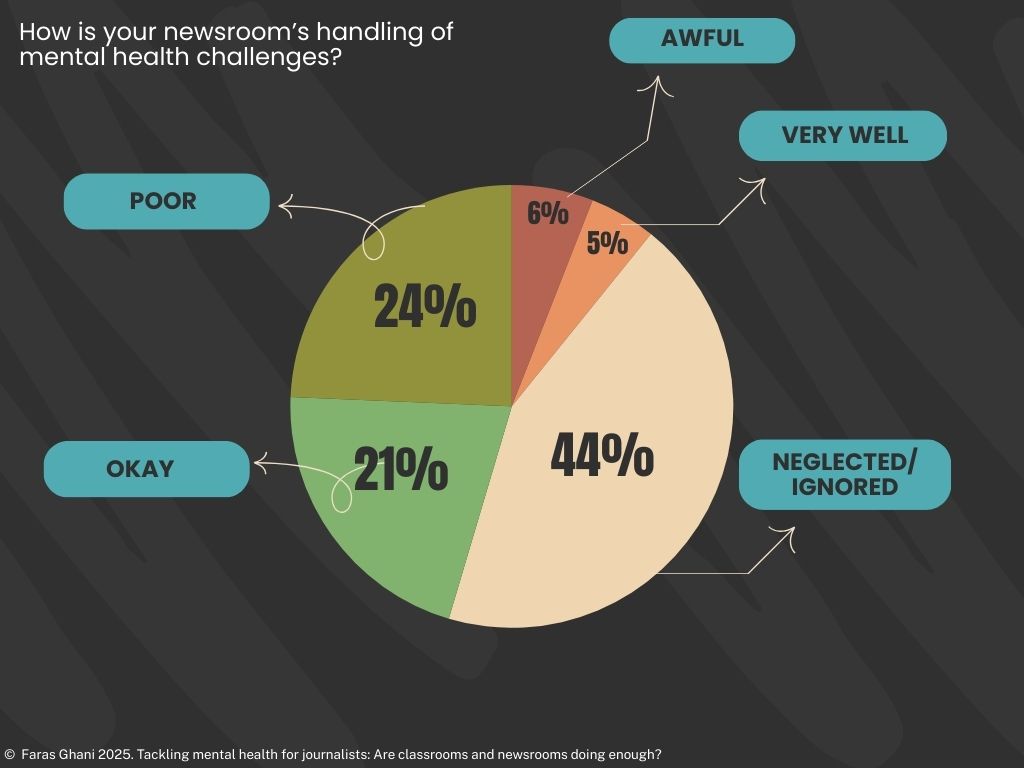

- Just under half of them termed their newsroom’s handling of mental health challenges as “neglected/ignored”.

- More than three quarters said mental health remains a taboo topic in their newsrooms.

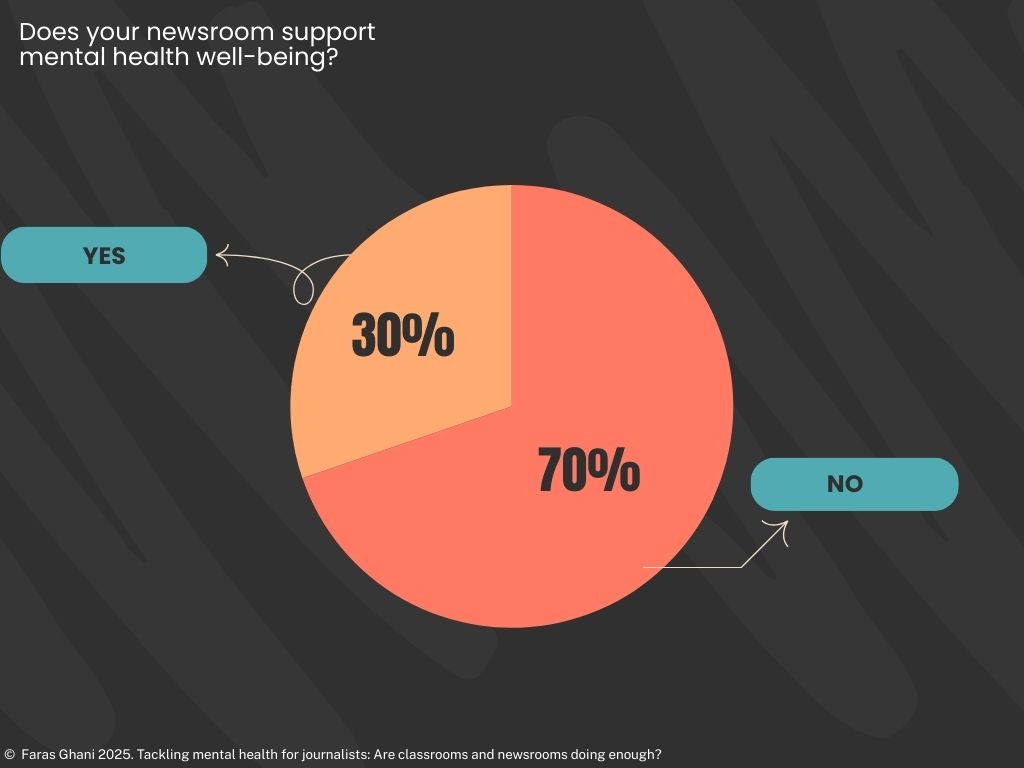

- Almost 70 percent said their newsroom did not support mental health well-being.

Methodology and Sample

The survey was conducted from March 13 to April 14. A total of 300 participants responded, comprising 185 journalists, 100 students, and 15 faculty members. The respondents represented wide geographic diversity: the journalists came from 38 nationalities, students from 28 countries, and faculty from 11 countries.

In India, a young entertainment journalist excited to be part of a new newsroom described the toxicity where expectations spiraled beyond reason and workload that kept them there “24/7”.

A seasoned journalist in Albania experienced workplace challenges that continue to affect her deeply. She said she resigned from her job “due to bullying, toxicity and a really terrible, terrible work environment”.

In Iran, a female journalist was battling the emotions when reporting on wars and killings in a male-dominated newsroom.

Elsewhere, staff was told not to take break – in contradiction with a clear HR policy – because there were not enough people to cover them.

‘Stress Levels for Journalists Remain High’

In 2025, a study published by Muck Rack revealed that “stress levels for journalists remain high” with half of the more than 430 respondents considering leaving their job this year and more than one-third unsure of how long they’ll stay in the industry.

In 2025, a study published by Muck Rack revealed that “stress levels for journalists remain high” with half of the more than 430 respondents considering leaving their job this year and more than one-third unsure of how long they’ll stay in the industry.

The same survey found that 38 percent of journalists said their mental health has declined over the last year.

In an article for Women in News, Bokani King wrote: “As journalists, we dedicate time to covering other people’s mental health struggles but seldom focus on our well-being. The demands of the job often overshadow our mental health needs, raising the question: are we so focused on others’ stories that we ignore our own?”

“Being an independent journalist, the media outlets do not support us. I am at my own mercy and have never got any support from the outlet I reported for,” said a journalist based in Indian-administered Kashmir.

In a survey, The Self-Investigation reported high levels of anxiety (60%) among journalists, adding that levels of post-traumatic stress disorder and burnout are on the rise and concluded that “tackling mental health in the media is an urgent issue”.

Aldara Martitegui, co-founder of The Self-Investigation, said that while the taboo was lessening, “there’s still a long way to go to destigmatise mental health in newsrooms as well as in society in general”.

Aldara Martitegui, co-founder of The Self-Investigation, said that while the taboo was lessening, “there’s still a long way to go to destigmatise mental health in newsrooms as well as in society in general”.

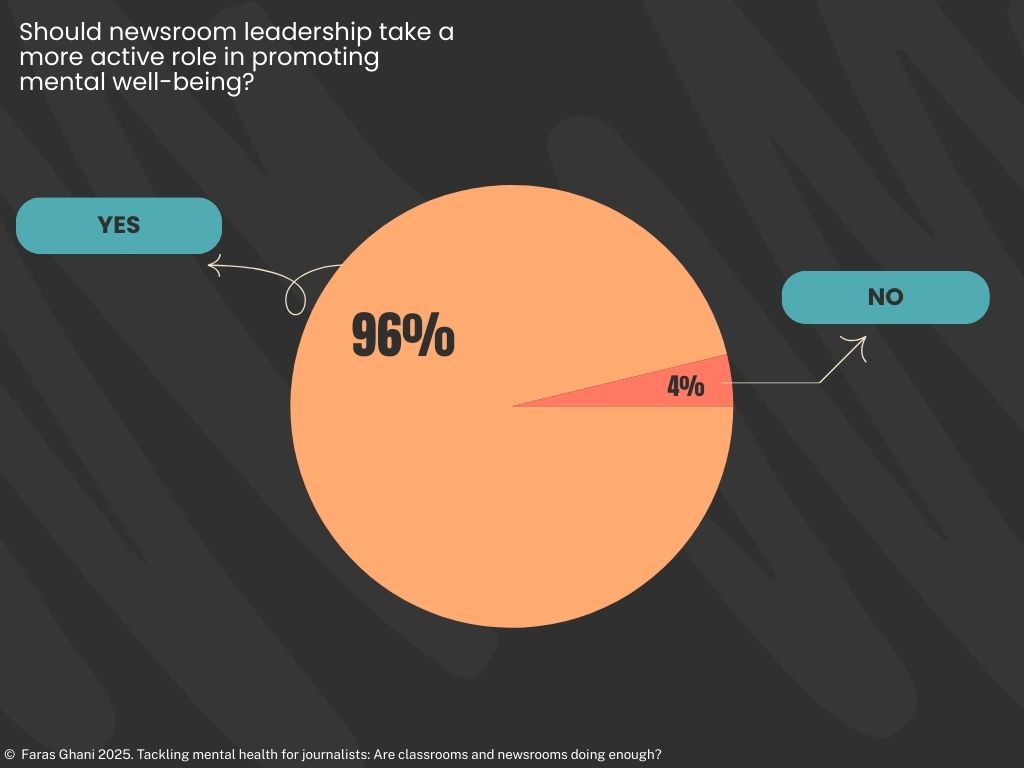

She stressed that “taking this issue seriously in newsrooms and giving it the same importance as writing, editing, reporting and audience interaction would be a huge change in journalistic culture”.

A 2020 Reuters Institute survey revealed that 70 percent of international journalists reported psychological distress, and 11 percent showed symptoms of PTSD.

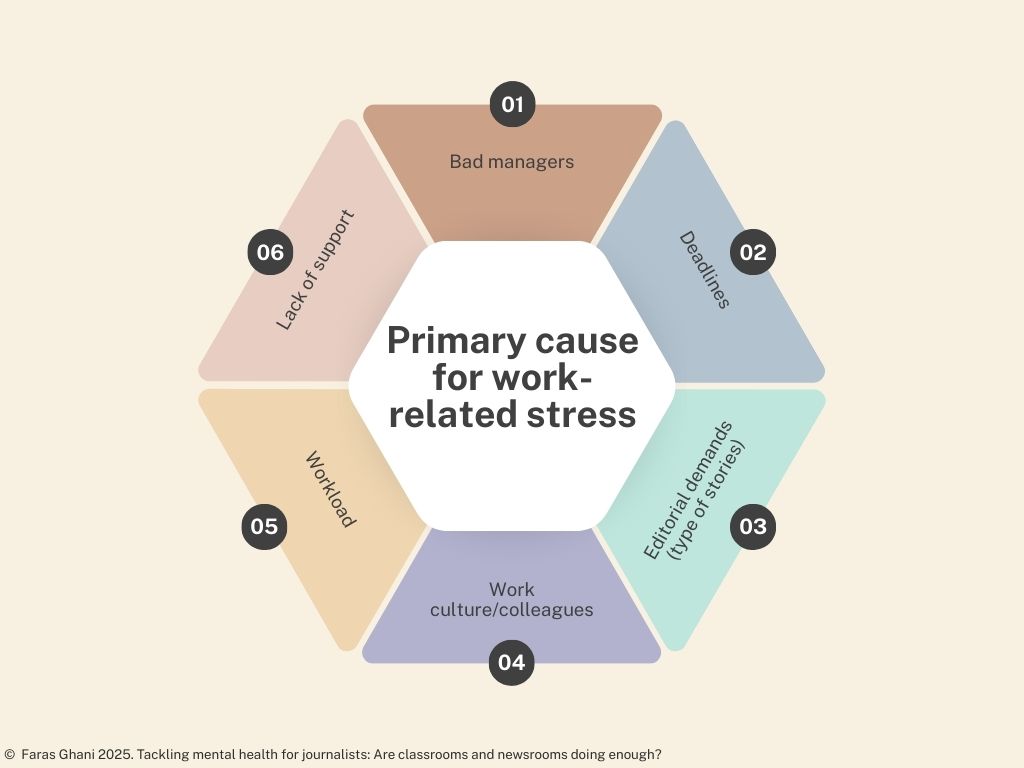

The mental health in newsrooms research revealed that 77 percent of respondents said their personal life has been affected by workload and pressure, with reasons ranging from lack of support, bad managers, work culture, including toxicity and bullying to editorial demands and workload.

Dr Jason Wang, a psychotherapist, says that “when the stress and the anxiety and everything else is too much, it’s impossible to compartmentalise in a healthy way”.

“Stress leaks out at home, even though you’re trying not to let it leak out,” he said.

Are Field Journalists Worse Off?

While journalists working in a newsroom have some sort of safety within the physical boundaries of the building and the organisations, freelancers and reporters in the field say they have often felt let down by the media organisations they represent or report for.

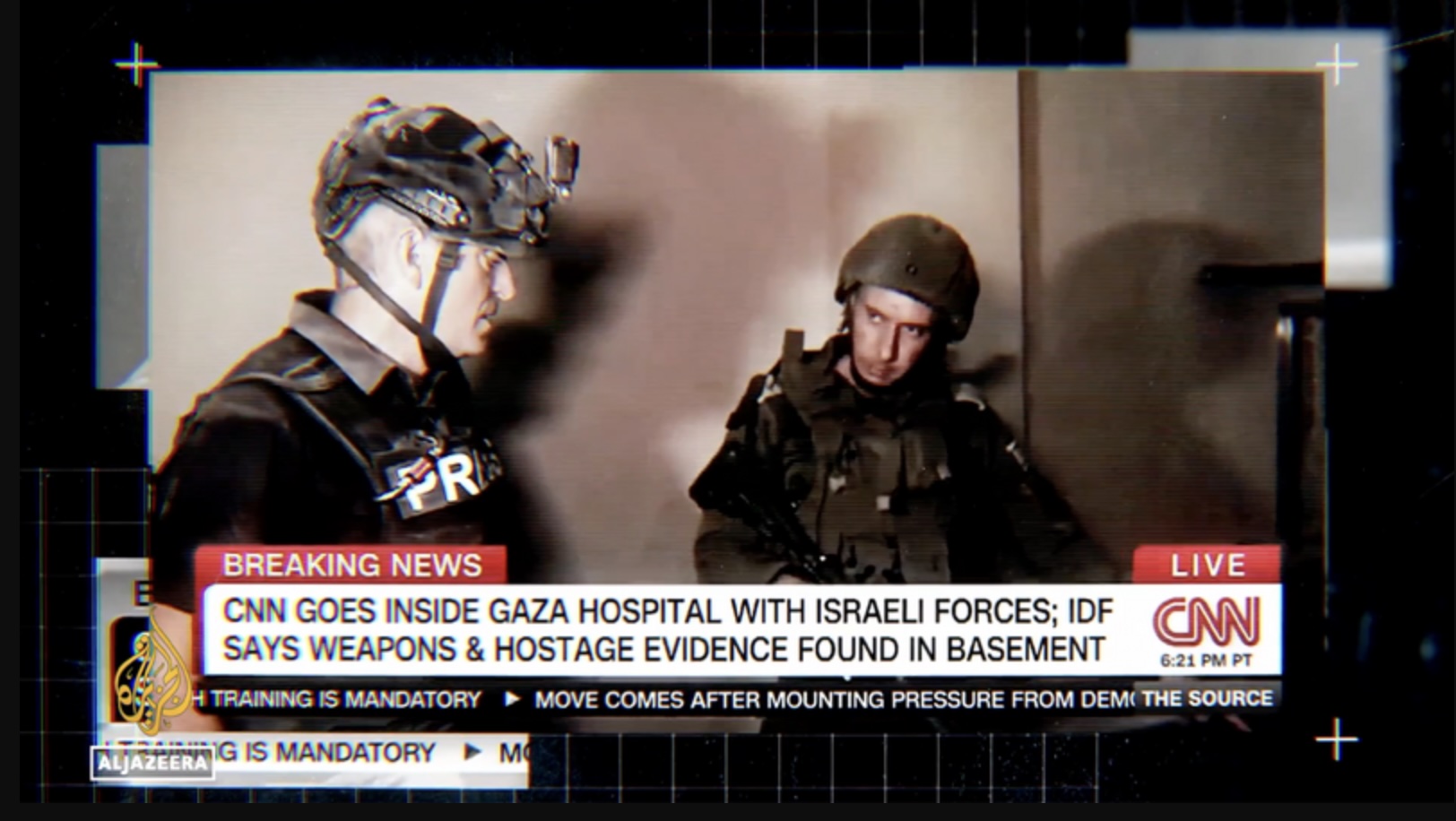

In Gaza, at least 250 journalists and media workers have been killed by Israeli attacks which have made this war the deadliest conflict for media workers ever recorded, according to Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

In Gaza, at least 250 journalists and media workers have been killed by Israeli attacks which have made this war the deadliest conflict for media workers ever recorded, according to Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

In November 2024, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) released a report concluding that “mental health is not a priority for media employing journalists in Gaza”.

Indian-administered Kashmir is another location where journalists are being continuously targeted for reporting on atrocities. Since the revocation of Article 370 in 2019 by the Indian government taking away the autonomy of the region, press freedom has sharply declined.

Journalists in Kashmir have been detained, questioned and harassed by authorities. Some have been threatened. Others have had their passports confiscated. Independent media outlets have been targeted and closed.

Journalists in Kashmir have been detained, questioned and harassed by authorities. Some have been threatened. Others have had their passports confiscated. Independent media outlets have been targeted and closed.

Mirroring the ARIJ report findings, freelance or independent journalists in Kashmir felt let down and unsupported by the media outlets they contributed to.

“Being an independent journalist, the media outlets do not support us. I am at my own mercy and have never got any support from the outlet I reported for,” said a journalist based in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Substance abuse and use of antidepressants have also become common among journalists there. In addition to personal safety, the fear of harm coming to one’s family is also a worry that stays with journalists in Kashmir, affecting the physical as well as mental well-being.

The world of journalism looks unlikely to change. Demands will likely increase, and despite evolving consumption habits, journalists, driven by passion, need and pressure, will continue to strive for more.

How Can Journalists Look After Themselves?

But ultimately, how much is too much? And how can journalists care for themselves amidst demanding conditions that are breaking them down? What should they do if they exhibit symptoms of mental distress?

“Detox yourself regularly and mentally declutter your environment,” said Dr Asma Naheed, an educational psychologist based in the UAE.

“Keep your work area and work life clean and safe so you can feel calm. Increase water intake, sleep and keep boundaries.”

Dr Naheed emphasised on three points:

Exercise

Exercise- Shut down

- Switch off

“You need to have a circle outside of work. Work extra hard on your relationships. You need to have your ‘me time’, time with family and playful activities. Go running, swimming, hiking and take part in playful activities.

“Normalcy is a luxury. Be normal. Don’t be exceptional.”

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reported that working in “high-intensity environments, encountering distressing news and images, and undertaking dangerous front-line assignments can lead to long-term psychological trauma for journalists”.

It advised journalists that when stress “starts to disrupt day-to-day activities, journalists should take a step back from their duties and consider taking a leave of absence”.

They should then:

- Rest and engage in relaxing activities

- Assess and address trauma with professional support

- Rebuild connections and establish healthy routines

- Build mental resilience

However, experts contend that improving the situation should not fall solely on individual journalists.

The contributing factors are multiple and often out of their control – newsroom environment, management behaviour, flawed workflows and workload. Therefore, remedial measures need to be taken across the board and not just on an individual basis.

Should Journalism Students be Made Aware of the Occupational Hazards?

With so much at stake when it comes to well-being in the newsroom, are students and recent graduates entering the demanding world of journalism well informed and well prepared?

Universities and institutions offering journalism, media or related curricula need to ensure students are not only aware of the challenges but also equip them with coping mechanisms.

The research on mental health in newsroom revealed that:

The research on mental health in newsroom revealed that:

- Just over 55 percent of journalism or related curriculum students reported no classroom discussions on mental health challenges.

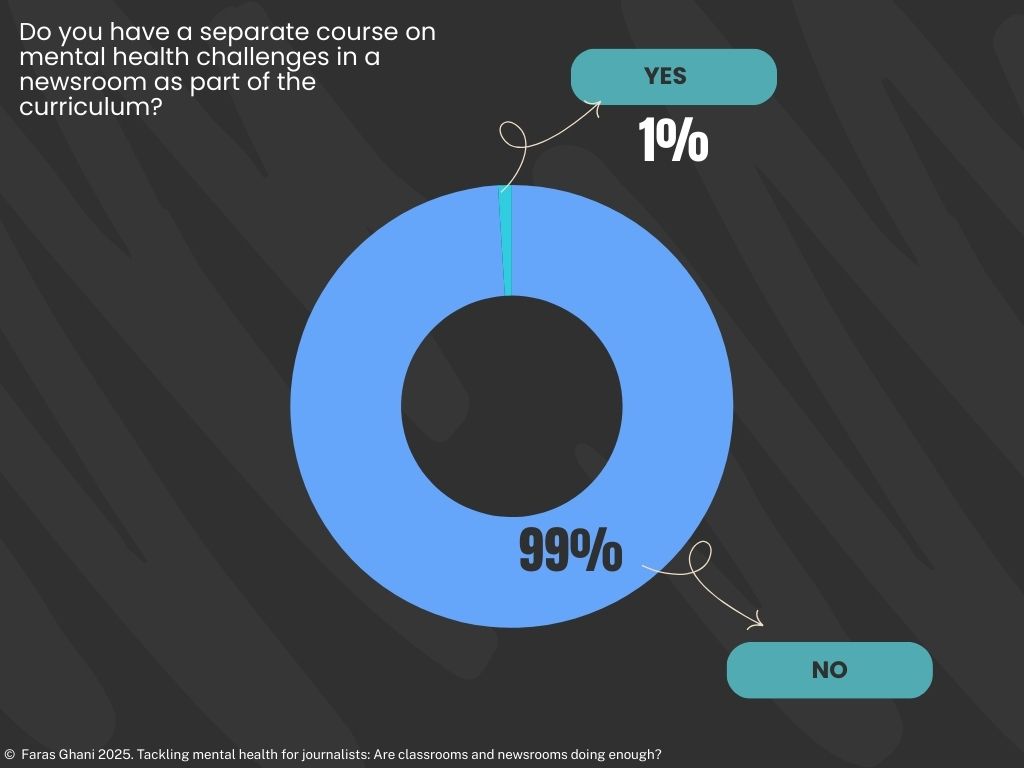

- Only 1 percent had a separate course on mental health as part of their curriculum.

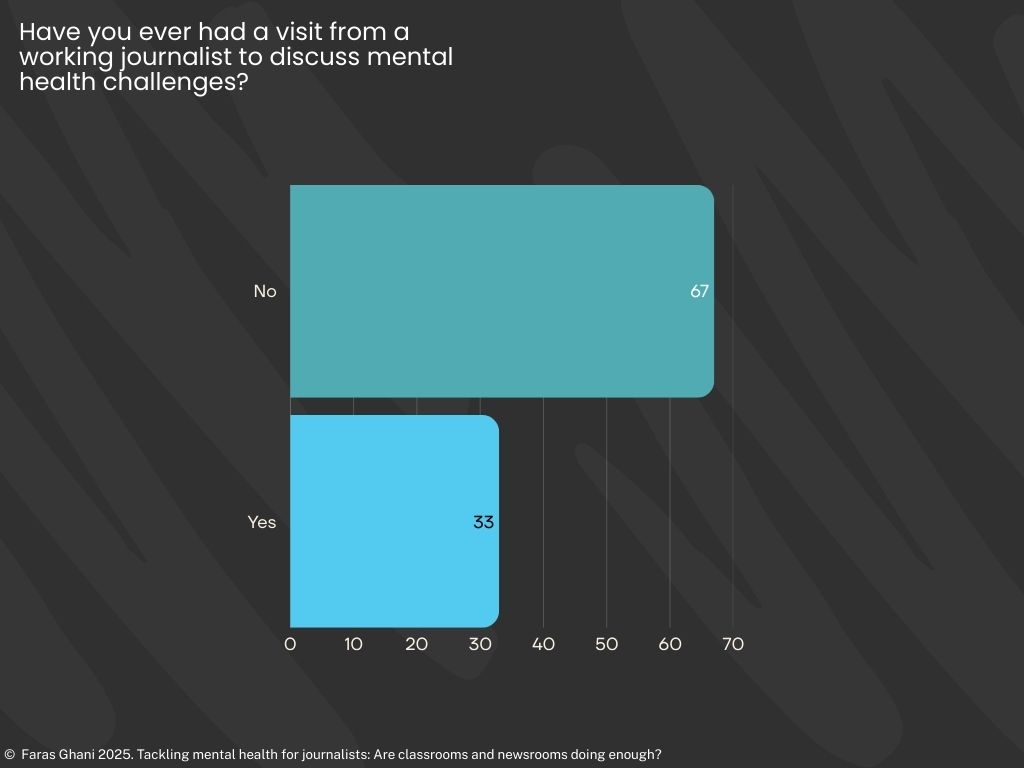

- Just 33 percent had ever received a visit from a working journalist to discuss mental health challenges.

- Almost 92 percent said mental health needs to be a more important topic in journalism schools.

Why then is it not taken as seriously as writing, editing, reporting, ethics or photography?

Dr Samia Manzoor, Assistant Professor at Bahauddin Zakariya University, Pakistan, attributes this to a lack of awareness among educators.

“It’s because we don’t know about it, we don’t know the severity of the situation or its impact,” said Dr Manzoor. “This is why we’re unable to educate the students. We cannot teach them something that we ourselves are unaware of.”

She argued that courses developed by academics “will definitely have major deficiencies” because “being an academic, I can only have a remote idea of the kind of stress that a journalist is enduring when they are in the field”.

She argued that courses developed by academics “will definitely have major deficiencies” because “being an academic, I can only have a remote idea of the kind of stress that a journalist is enduring when they are in the field”.

Pheladi Sethusa, a lecturer at Wits Centre for Journalism in South Africa, echoes these sentiments.

She noted that mental health topics are not prioritised in journalism schools because educators themselves were “molded in environments that were not open to conversations about mental health illnesses, about how to look after your mental health, about giving people the time and space to treat any diagnoses that they might be under”.

A quarter of journalism students said they do not feel prepared to address mental health challenges as professional journalists.

Sethusa argues that despite some opinions against it, the research on how journalists are affected by trauma shows “there is an obvious need arising for there to be some kind of teaching about how journalists’ mental health can be affected by the profession as well as how to cope with it”.