With a rising number of journalists in India receiving ‘summons’ from the police and even finding themselves in prison just for doing their jobs, we ask - why has the profession come under so much pressure in recent years?

The established "theoretical" role of the press in a democracy is that of being a watchdog - a fourth pillar within a democracy which keeps the other pillars in check. It is meant to monitor the workings of the public and private entities and foster justice based on truth, objectivity, and accuracy.

But throughout modern history, the tenets of both democracy and journalism have proven to be debatable and non exhaustive. Add to that the heterogeneity of India, and we have ourselves a complex webwork of overlapping realities.

Journalism in India seems to have taken on the role of a “rogue” democratic pillar to perfection. While some attribute it to the commercialisation of news and “infotainment”, others blame certain political ideologies. Almost all agree that journalistic autonomy in India is falling.

Widespread self-censorship

“It certainly takes more courage to be a journalist or reporter now than it did a few years ago,” says Rega Jha, founder and former editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed India. “Or to be any sort of cultural voice committed to megaphoning any criticism - ie truth - about Hindutva, the BJP, the RSS, or any of their leaders. Through Modi’s first term, the government spent a lot of time and resources, via multiple instruments - coordinated harassment and boycott campaigns, increasing interventions by the censor board, vague FIRs (First Information Reports which the police compile when they receive information about a possible crime) - to let it be known that creating cultural and journalistic output that didn’t serve their agendas would have consequences,” adds Jha.

As recently as 2014 and 2015, she adds, big names such as the Bollywood stars Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan were voicing criticism of the government and Hindutva nationalism. “But the types of harassment and threats they then had to reckon with had a severely chilling effect to the point that it’s now unthinkable that they’d be as critical.

“Among those of us that aren’t megastars, it had the effect of wholly normalising the calculus that critiquing the Hindutva brigade means risking major legal backlash or vitriol and lack of safety. By their second term, this relatively ‘soft’ policing had escalated to regular arrests of journalists and activists, often over tweets or other output.”

If journalists uncover or report on any unpleasant truth about political parties, they will be called ‘anti-party’ or ‘anti-government’. No matter how much the journalist puts in, those directly in-charge of revenue are the final gatekeepers, and the truth rarely goes on-air

All this has culminated in widespread self-censorship among writers and other content creators, she says, many of whom would now rather keep their politics to themselves than risk upsetting the establishment.

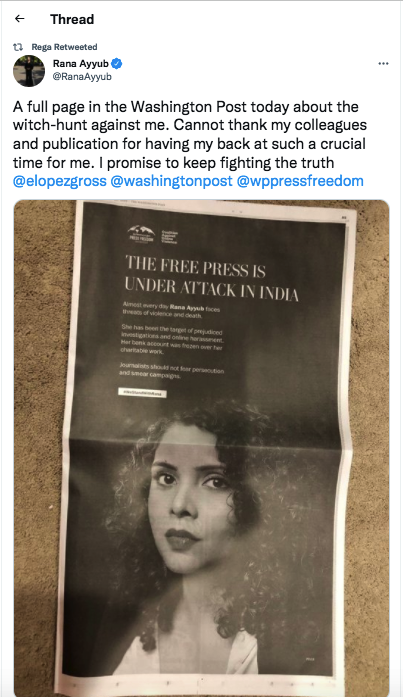

Jha continues: “I unfortunately count myself among this somewhat-silenced cohort, though I hope I’m able to muster the courage to change that. I take huge amounts of inspiration from folks still committed to large-scale dissemination of the truth - folks at The Wire, Caravan, Article14, AltNews, Rana Ayyub on Substack, and more - who stand for the fact that it’s still possible and is, in fact, crucial.”

it is, of course, too simplistic to attribute the decrease of journalistic autonomy in India to just a single political party.

It is also important to acknowledge the events of history that shaped media laws and revenue models of media houses. Indeed, the Free Press Index of India has been dropping since 2002. In 2010, India ranked 122 out of 178 countries. According to Reporters Without Borders, India slipped 17 places from its previous ranking mainly due to violence in Kashmir. Apart from the rise of neoliberalism, right-wing nationalist political parties, and the shift in economic models for revenue generation, major contributing factors to a sustained decrease in journalistic autonomy include political violence and partisan journalism.

All about revenue

Aman Bhardwaj, a journalist working across Haryana, Punjab and Himachal Pradesh - who has had several FIRs filed against him - spoke to Al Jazeera Journalism Review on his way back from the “party office”. He was sitting in his car under a bright streetlamp as pedestrians and street-hawkers passed by. The setting of the conversation is important because, he says, it symbolises everything he wants to say about “political parallelism” and how corporate media’s boundless quest to generate revenue strips journalists of the little autonomy left to them.

Disgruntled at the new trend of media organisations and political parties working together, he begins our interview by saying that the “political class” has been dominating media organisations, influencing journalism through advertising and demanding that journalists act as their instruments for publicity.

“When you work for regional channels, there is an influence of regional politics on the channel - mainly by political parties that are either already in power or those that want to come to power,” he says. “The parties that want to come to power will force channels to run commercials for them so they may win the vote. Those that are already in power want to run government advertisements and try to make their popularity last longer.

“When I used to work for a national channel, there was an influence of national politics. While reporting for this channel, I faced an FIR for one of my stories. There is always pressure on channels from political actors to censor the output.”

Political actors do not want the reality to reach the public, he says. “Whatever level of geography your story reaches, the corresponding political influence will accompany it. If it is a district-level story, then the district politics follows. If it is a state-level story, then state politics follows it and so on,” he adds.

Bhardwaj says he believes that the problem of revenue is at the core of the relationship between politics and the media. “The channels never refuse to run advertisements of any political party because the channels want revenue. When they see revenue increasing drastically once they stop covering any negative news about a political party, their perception shifts, and things begin to change.

“The channels realise that they do not have to compromise much on anything or do any direct favours except put a stop to covering the negative news about political parties. Without advertisements, generating revenue is next to impossible,” he says. “Journalists, who are employees of the channels, are then told that working for money will entail doing what the channel wants them to do, which means money becomes a factor in reduced autonomy.”

If journalists try to uncover the mechanism of these hidden ways in which political parallelism plays out, then they are labelled as “anti-government” or “anti-party”, says Bhardwaj.

Frankly, there is not much left of the role of a journalist. They are taken off air. Their beats are taken away from them. Overall, they are told there will be consequences if they do not remain compliant employees

“There are many ways in which a journalist is told how not to offend the powers that be. For instance, elections in Punjab [2022] are coming up, so journalists have been told not to cover any negative news about any political parties, including protests by the people or public demands. Just because a political party has paid for more advertisements with a channel, journalists working for the channel must report in a way that portrays the party as the better option for the upcoming elections.”

Bhardwaj says he believes that editorial decisions of news channels have become almost entirely dependent on revenue, and therefore aim to appease those actors within democracy that can bring maximum profits. “As a journalist, an employee of the channel, I cannot walk up to my editors and tell them we’re not running this. My editors will tell me that the political party is bringing us 500,000 so I can decide what to run when I bring them that much. Revenue is what the channel wants, so beyond a point, a journalist cannot do much to bring change unless that change means the channel will get more money.”

Is there anything that journalists can do to change this? He believes not much: “Frankly, there is not much left of the role of a journalist. They are taken off air. Their beats are taken away from them. Overall, they are told there will be consequences if they do not remain compliant employees.

“The need to run anti-party content begins and stops at advertising. The only time a channel will run a negative story about a political party is when they want to force the political party to give them revenue to run more advertisements. Even consumers of news now want drama when they watch news, so the bad standards of news production spread around like wildfire. Smaller channels are inspired by what the big channels are doing, and this becomes the norm.”

According to Bhardwaj: “If journalists uncover or report on any unpleasant truth about political parties, they will be called anti-party or anti-government. No matter how much the journalist puts in, those directly in-charge of revenue are the final gatekeepers, and the truth rarely goes on-air.”

He attributes the increased emphasis on profit-making partly to the digitalisation of the media. “People have started to learn how to make more money ever since things went digital. Up until a few years ago, online news portals did not know about the wonders that advertisements could do for their revenue. Digitalisation has become a harbinger for aggressive profit-making, and individual journalists, and journalism at large, suffers because of it.”

Reported to the police - for telling the truth

Bhardwaj was working with a national media network when he did an investigative story at a time when COVID-19 was at its peak in Himachal Pradesh. The government was issuing COVID e-passes for anyone entering Himachal Pradesh, and the verification required for the pass was not working properly.

He applied for a pass for “Donald Trump” and “Amitabh Bachchan” with his own mobile number and Aadhaar card to try to prove that the authentic verification process was flawed.

As he expected, the passes were generated, and he had the proof he needed for his story. Once he received the passes, he ran the story explaining the farce that the information verification process behind these e-passes was. The story blew up at the state level and was then picked up by national outlets.

Within eight to nine hours of the story coming out, Bhardwaj was facing an FIR. Authorities seized his personal phone which he had used to generate the e-pass. They seized his home Wi-Fi.

He is from Himachal, so he says he did not need the pass in the first place. He says the charges pressed on him regarding the IT act would only actually apply if he had made a false pass and tried to use it. He says there was also a charge of “spreading misinformation”, “but there was no misinformation because I had personally applied for the e-pass and received it through the government. The only reason I used the pass or did the whole process was for public awareness. I was just doing my job”.

This story led Bhardwaj being transferred to another state, having his beat taken away from him, and told to work “on desk” as he would no longer be allowed to report on the ground for the channel.

Because Bhardwaj believes the grossly capitalist revenue models and profit-making being the sole aim of many media organisations are at the core of decreased journalistic autonomy, he does not blame any single political party.

“No party wants the truth to reach the people. In Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party is doing it. In Himachal Pradesh, BJP is doing it. In Punjab, Congress has done it. More or less, they are all on the same track. If one party started it, the others learned from them.

“I was at a press conference for a political party and protestors with black flags showed up outside. I just opened the door to see what was happening, when the PR manager for the party came and told me I don’t have to cover this. I told her it was my job to see what I had to cover. So, she rang up my office and told my editor to send another journalist. These are the kinds of things that happen.

“After the fourth or the fifth time, reporters will start censoring themselves.”

Individuals versus institutions

R Rajagopal, Editor of The Telegraph newspaper, says there have always been checks and balances for individual journalistic autonomy because journalists all over the world work for organisations that have their own priorities, but what is different now is that autonomy has changed for institutions. “Especially since 2014, journalistic autonomy is not only eroding, but it is eroding very fast,” says Rajagopal.

According to him, there is a dangerously increased amount of self-censorship among journalists. He says it would be difficult to blame any official government policies put in place to tame or control the media, but there have been instances of individuals being targeted or persecuted, which has been taken as a sign by others and has increased self-censorship at the individual-level.

“At the institutional level, several newspapers feel intimidated about criticising the government or giving space to the opposition. So, in that way freedom has definitely shrunk,” he adds.

Rajagopal says he personally experiences self-censorship every day. Other than arbitrary arrests and threats to journalists from authorities, there are also private investors who file defamation cases, which is something that has always happened, but the numbers have gone up by a lot in the last 10 years. “The government and media are anyway not supposed to be friendly, which is fine, but when it goes from that to a hostile relationship, it’s a problem. And in India, we can see a very hostile relationship,” he says.

“Recently, some norms have been changed by a media accreditation committee. [The norms] are so loosely worded that if you write something against the country or against the government, it can invite consequences. Often the distinction between the country and government blurs. The government is used as a synonym for the country, which is very dangerous. No one or nothing should be above criticism. In a democracy that is how it should work,” he added.

Rajagopal says that the broadcasting laws in India are very strict because when they were written in the 1990s, they were meant for telecasting sporting events, which means commercial interests were involved and there was a need for several checks and balances. “But once news media came, those laws should either have been overruled or modified. Since the government at the time did not interfere or meddle, no one gave much attention to it, but this current government is using those clauses, which preceded them, to harass journalists,” he says.

According to him, the lack of autonomy for institutions has a worse impact because individual journalists are seen as dispensable. If one journalist loses their job within an organisation, someone else will take their place the next day.

However, if institutions are unable to or refuse to carry the truth of the time, then he says it is “a grave loss for society”. When mainstream newspapers or news organisations refuse to carry a story or choose to carry a manipulated version of it, then eventually, that doctored story will become the history of the time.

the lack of autonomy for institutions has a worse impact because individual journalists are seen as dispensable. If one journalist loses their job within an organisation, someone else will take their place the next day

“Ten years from now, if somebody Googles today, and sees the same lies in 10 newspapers, then naturally the citizen will assume that this is what must have happened at the time. Nuances make all the difference, and most of these government-friendly newspapers are very black and white. There is no nuance or grey area. Everything is a binary to them. So this narrative is very dangerous. It becomes part of recorded history, which is a problem.”

'Failing to fulfil its basic function'

Rajagopal says he believes that mainstream media in India is failing to fulfil the very basic function of news media in a democracy, which is to be a watchdog. In fact, he says, if ever there is no strong opposition for the government due a huge election mandate, then it is the duty of the media to act as an opposition. However, according to him, it is very clear when you watch most mainstream news channels that there is an eagerness to please those in power, and an equal alertness to avoid any voices of opposition.

He says a more worrying factor is that most media, especially television channels, have been taken over by individuals with interests in other fields such as corporate.

“What happens is when you have a wide array of interests and when you have very strong central agencies or enforcement agencies that can be misused, these corporates are always scared of the government because their other operations depend on keeping the government happy.”

He says that if these entities conduct journalism the way it should be, then their other operations can get affected. So, if someone has multiple interests and media is just one of them, then self-interests will dictate that one pleases, appeases, or pacifies the government instead of criticising or antagonising them so that their other interests remain unaffected.

Additionally, he says that another worrying factor to reduced autonomy is that media in India is still a majority community, upper-caste-driven profession, with an array of communal elements. While these inherent communal biases were always there, they have now found an outlet, and worse, a legitimacy. “Earlier in newsrooms, one of the most basic qualifications was that you had to be a secular person, but that is no longer the case. The language also changes. Another dangerous thing is that words like religion, government and nation are being used as synonyms. So, when they are talking to a liberal audience, they will drop ‘religion’ and talk of the ‘country’ - but we know what they’re trying to say,” he adds.

Rajagopal says things have changed with time, but he has hope for the next generation of newsroom professionals and journalist, who he says are much more aware of sociopolitical affairs than his generation was, “[Back in our time] it became an old-fashioned thing to say that journalism has a responsibility towards society. If you said that, people would laugh. That is one of the reasons why our values got derailed in the newsrooms.”

A rising number of cases against journalists

Ismat Ara, a journalist from The Wire, speaks about how the number of police cases against journalists have increased over the past few years, even against celebrated journalists who are known by Indians across states, languages and regions. In fact, in some cases, popular voices of dissent have been more obviously targeted than their lesser-known counterparts. In other cases, outspoken journalists have risen in popularity after they have been targeted, jailed, or arbitrarily arrested, and public discourse has initiated to defend the journalists or criticise their unfair trials.

Last year, on January 26 during the Farmers’ protests, a protester had died, and what ensued after was a whirlwind of news reports and police complaints against journalists. This is one case in which Ara faced an FIR for her on-ground reporting.

“We were all, as journalists, reporting what we were seeing. When you are on the ground, you report certain things you hear. When you are reporting from the ground, you do not really have the time to verify all the information that you are getting, and as and when you do get the verification, you update it. So that is exactly how I went about it,” she says.

The day the death happened, she says, there were farmers who were saying that the police had shot him. So, Ara’s first tweet said that farmers were alleging that he had been shot by the police. She says she immediately spoke to the police because she knew “that this was sort of risky and [she] did not want that tweet to be out there in isolation”. For her next tweet, she added the police’s version and said more details awaited. However, despite her efforts to be objective in reporting the incidents, an FIR was filed against her.

There have also been instances where regional reporters have been targeted. She says a journalist during the first lockdown, sometime in 2020, had exposed the midday meal scheme and he did a report on how students in government schools were being fed poor quality food. He faced trouble from the police as a result and was arrested for a while, according to Ara.

Ara also talks about the Siddique Kappan case, which she calls a “classic case” that illustrates the fall in journalistic autonomy in India.

Kappan is a journalist from Kerala, who set out to report on the rape of a young Dalit woman in Uttar Pradesh “like the hundreds of other journalists who had been reporting on it,” says Ara. However, on his way to cover the incident, Kappan was arrested along with the people in his car, including the driver who had no prior links to Kappan. Among other charges, Kappan faced charges of allegedly having “terrorist connections” and “communal incitement”.

A recent news story about journalists in Hong Kong who have changed their professions was a hit among his fellow journalists in Kashmir, he adds. ‘We were joking about how we should also switch our jobs'

Ara says Kappan’s arrest was a clear attack on journalistic autonomy, and arresting the driver was “outright bizarre”. She remembers doing a story on the driver and says that he was still paying the instalments for the car he had recently bought in which he was driving Kappan to the spot, which is one of the reasons he took up this sort of assignment.

Being Muslim and a journalist in India

There have been several instances of assault and abuse against journalists in India, especially during times of communal conflict and political violence. Ara recalls one incident from the Delhi riots when a Muslim journalist had to be rescued from a mob by his Hindu friend, who had to convince the mob that the journalist was a Hindu and that they should let him go. Ara says: “I think what I’m trying to say here is that there is of course, a reducing freedom of the press in India, but at the same time, the Muslim press and journalists, and Muslims in general, are facing an increased brunt of everything that is going on.”

She says she does not go out on the field thinking she is a Muslim reporter, or that she ought to report on certain issues because of her religious identity. Ara recalls covering protests from Right wing groups over the government in Delhi’s Dwarka passing a project to build a new Hajj House. “When you go into the field, talk to people, and try to cover a protest like this, you can’t really go and tell them that you’re a Muslim. It’s not that I am conscious that I am going as a Muslim, but I am being made to sort of reconsider my journalistic abilities because of my religious identity. When you go out there, you realise that it’s not safe to be a Muslim reporter, specifically covering issues of communalism because that is where you’re really at risk. People are charged up or emotional, and they will very casually make violent remarks.

“The country that we live in right now constantly makes you aware of your religious identity, even if you’re not intrinsically very aware or if you don’t want to be. People don’t have that choice anymore,” she adds.

Ara says there’s a brutally evident sense of impunity. She says she has seen it while covering stories of communalism on ground, but it is also evident in the notorious Bulli Bai case (Sulli Deal, a similar case, happened a year before that). In both of these cases, Muslim women - including Ara herself and the well-known Kashmiri journalist Quratulain Rehbar - were targeted, trolled, sexualised and mock-auctioned online.

However, no action was taken after the first case. “Months passed and there was absolutely no identification of any of the culprits. There was no update on the investigation either. It took them eight months, and then another FIR and another similar case to even start the investigation, and of course, even when they did start the investigation, it was after a lot of pressure was created from all sides,” she says.

“The people behind Bulli Bai are all kids. I’m not saying that they should not be held accountable for what they have done; of course, they should be held accountable. But this is just a symptom, this is not the disease,” says Ara.

She says instances like Bulli Bai are symptomatic of a larger disease, a larger systemic failure, which involves many organisations, hierarchies and levels. “I think there’s a nexus, if we can use that word, that promotes this kind of behaviour - from online trolling to physical danger to police threat or state threat - all of these things are working together,” she adds. Ara says even when religious identity is removed from the equation, journalists face multiple levels of threat when reporting from the field, including online trolling, physical danger and threats from the state.

“In the Bulli Bai case, I have constantly been trying to point to the fact that the threat is not just restricted to your digital screen because this photo of me (or all the other women) who have been targeted in this manner is out there. What if it goes out to someone who may act on it, who could possibly see me at some point, for example, and come and attack me or assault me? Who is to say that this will not convert into physical danger or physical action against me? There is always that danger,” says Ara.

Ara points out that the threat from the state is omnipresent. “There is always the threat from the state, from the government, and from the police. As a journalist, you have to think twice before you write something, and it’s very unfortunate.”

She says the police case filed against her for the story during the farmers’ protest was unfair because she had put all versions of the story out there - she had done her absolute best to produce balanced and unbiased reporting. By journalistic standards of objectivity, Ara had covered all bases. Despite this, the FIR filed against her stated that she was “causing unrest, in the name of religion, caste or communities”.

Ara says she believes that social media and online news portals, like The Wire and others, are now best placed to publish stories that mainstream media fails to tell and will strengthen over time. “At the end of the day, we hope that there is light at the end of the tunnel,” she says.

Journalism in Kashmir

The tale of Kashmir is a complicated one to tell, but of journalism in Kashmir, even more so. Perhaps the tale can begin with the fact that the teller who spoke to Al Jazeera Journalism Review chose to remain anonymous.

When I ask him why he wishes to remain anonymous, he simply says: “If things weren’t like they are, I would have no hesitation in giving my name.” A freelance journalist in Kashmir, he says he does not want to risk talking about something as “contentious as the freedom of journalists in Kashmir” by revealing his identity.

“It’s too risky,” he says. He asks me to omit many of the stories he shares with me during the interview from the article because they would make him identifiable.

He tells Al Jazeera Journalism Review that journalists in Kashmir have been receiving legal threats for just speaking the truth. He also says the atmosphere in Kashmir is suffocating, particularly for freelance and independent journalists.

“Most of my colleagues remain on the down low. They have self-censored, and they don’t write on issues anymore that may attract legal summons or police complaints,” he says. “Many of the freelance and independent journalists I know have left Kashmir and are now reporting from other parts of India.”

The government is used as a synonym for the country, which is very dangerous. No one or nothing should be above criticism. In a democracy that is how it should work

According to him, freelancers in Kashmir are especially at risk because they don’t have the backing of organisations. Since he left his job with a newspaper, he has been trying to establish himself as an independent journalist working out of Kashmir but, he says: “This choice is becoming unattainable now given the unprecedented attacks the authorities have launched on the free press in Kashmir and on independent journalists in Kashmir.”

He attributes the worsening of an already crippled state of journalism in Kashmir since 2005 to the revocation of Kashmir’s status as an autonomous state in 2019, and he says the COVID-19 pandemic only made things worse. The closure of the Kashmir Press Club earlier this year and the restrictions imposed by the government have proved to be a “death knell, making it very difficult for independent-minded journalists to work”.

He says he fears that legal harassment will only increase with time. The authorities’ use of media policies has effectively criminalised journalism in Kashmir and has rendered it a public relations exercise, according to him. “Any piece of journalistic output that does not conform to their interests is deemed ‘anti-national’. It has made investigative and independent journalism a very risky affair in Kashmir. My biggest fear is that over time, fewer and fewer independent and freelance journalists will be willing to operate out of Kashmir,” he says.

A recent news story about journalists in Hong Kong who have changed their professions was a hit among his fellow journalists in Kashmir, he adds. “We were joking about how we should also switch our jobs.”

However, he says, even if they wanted to change professions, Kashmiri journalists would have few prospects. While a journalist in Hong Kong might be able to open a restaurant because the economy is favourable, in Kashmir the situation is different.

Kashmiri journalists also face attacks by pro-government journalists. Indeed it was a group of pro-government journalists which arrived in January and took control of the Kashmir Press Club before closing it down altogether.

“The mainstream media is writing articles targeting well-meaning journalists, and social media campaigns are maligning independent journalists and voices from Kashmir,” he says. “There is a sense of impunity.” Even the journalists that are being legally targeted face baseless allegations, according to him. “[The journalists] don’t even dare to file defamation cases because they know nothing will come of it. This is journalism in Kashmir now,” he adds.

There is also a new breed of “nationalist journalists” which has appeared in Kashmir. Most of them, he says, are not Kashmiri. They appear to be able to write whatever they like about any journalist in Kashmir without any consequences. He says: “There is complete impunity for these people, and I think this unusual behaviour of these people shows that, somehow, they have the backing of the state.”

More than just a bleak future?

Was there ever a good time for journalism in Kashmir during his career? He says there was. “The current phase, especially after the revocation of the state’s autonomy, is the worst for journalism in Kashmir. Earlier, there was freedom to report critical stories from the region. I have reported some critical stories from Kashmir myself. If the authorities disagreed, they would simply issue rebuttals or insist on publishing corrective statements. That was it, and that is the practice all over the world. But that’s not the case now. Journalists now receive direct threats for their stories or personal social media posts. This is the norm now,” he adds.

“I think journalists are not only storytellers, but also watchdogs in society. So, a democratic society ought to need journalists,” he says. Now, the profession is hanging by a thread.

“If I lose my job, I don’t have enough alternatives to work somewhere else and I may not have enough to support myself as an independent journalist. Even with my two decades of experience, it is becoming difficult to sustain myself as a freelance journalist. It’s not an easy job to sustain as an independent journalist, given the kind of media landscape in India because there are few organisations which support that kind of journalism,” he adds.

Even when there are provisions in law to protect journalists, media houses know how to work around them. “There was a Working Journalist Act in 1955, which recommends certain provisions such as minimum wages, leaves with pay, enough period of notice, and working hours for print journalists but now in many cases journalists are being fired on a very short notice.” The Act does not apply to “digital” journalists, he explains, and is therefore now very easy to bypass.

He says many of his stories have been “killed” by editors, particularly since 2014. “There is heavy gatekeeping in the newsrooms. We study a lot about objectivity as students, but in the real world, things are very different in newsrooms,” he adds.

The future of journalism in Kashmir? “Bleak,” is how he describes it.

The space for stories that matter has shrunk, and they are becoming more and more difficult to report. Media organisations do not want to risk conflict with the authorities, so they will discourage reporters who are insisting on writing those kinds of stories.

“I think the biggest factor has to be the biases of the ruling party towards the media. They definitely want to control the narrative. They want to make sure none of what they call ‘negative stories’ get out,” he said.

“There’s a silver lining,” says our anonymous reporter. “I think it’s the only silver lining that journalists in Kashmir are looking towards. I think a major change in the political dispensation will influence the working atmosphere of journalists in Kashmir. I think if there is an elected government, at least it's accountable.”

“But right now, the situation is very difficult,” he quickly adds.

The reality of the situation is pressing. And there are few who could be more realistic than journalists who have the values of accuracy, truth and objectivity branded onto them - whether they get to put those values to use, and when, is a question still awaiting an answer.

It turns out that hope is stubborn, perhaps especially when it springs from a community of harassed journalists.