Governments in the Middle East have grown less tolerant of criticism over the last two decades, whether it be from a domestic or foreign source. States have cracked down on media freedoms and tightened their grip on domestic media narratives to stifle criticism. The result is a homogeneity of media narratives across the region.

This state control over the media has pushed audiences in the Middle East to turn towards international media outlets and social media platforms to get their news. Ultimately, this has left audiences vulnerable to disinformation campaigns, eroded their faith in state narratives, and undermined trust in state capacity.

This is not to say that all alternative media options are malicious or carry malign intent, however, some of said alternative media options have been proven to be associated with disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda.

The Arab world—like the rest of the world—has seen an influx of information due to the introduction of social media. The ability to disseminate information, once monopolized by the state and traditional media entities, has become open to all individuals, entities and agencies through social media.

This shift in information control has left state attempts to control media narratives unsuccessful, and has caused fierce competition between the state and alternative media outlets. The mission of alternative media, to contradict the state narrative and present itself as the voice of the truth, brings it into direct conflict with the state.

Studies suggest that less credible sources of information use multiple practices to dismiss and disengage audiences from state narratives. Oftentimes stories shared by said sources lack the basic standards of journalism or research. Instead, they use leaked information, conspiracy theories and the spread of baseless accusations to shake their audiences’ trust in state narratives.

Recent events in Jordan provide a clear example of multiple practices aiming to disrupt trust in state narrative. Recent disinformation flashpoints have been the “plot” which involved prince Hamzah, the oxygen cuts in Salt Hospital which resulted in seven deaths, and the domestic opposition movement (known as Hirak in Arabic) commemorating its 10th anniversary.

In each instance, disinformation quickly proliferated over social media. False information swirled about Bassem Awadallah, one of the main figures accused of carrying out seditious activity in Jordan. Exaggerated death tolls were shared after the Salt incident. Social media behavior called for mass demonstrations by Hirak, a stark contrast with the reality on the streets of Jordan.

At the same time, the Jordanian government insisted on maintaining its strong grip on the media narrative, causing suspicion towards announcements on media and pushing people towards social media and other less credible sources of information, leaving them vulnerable to sensationalism and provocative narratives.

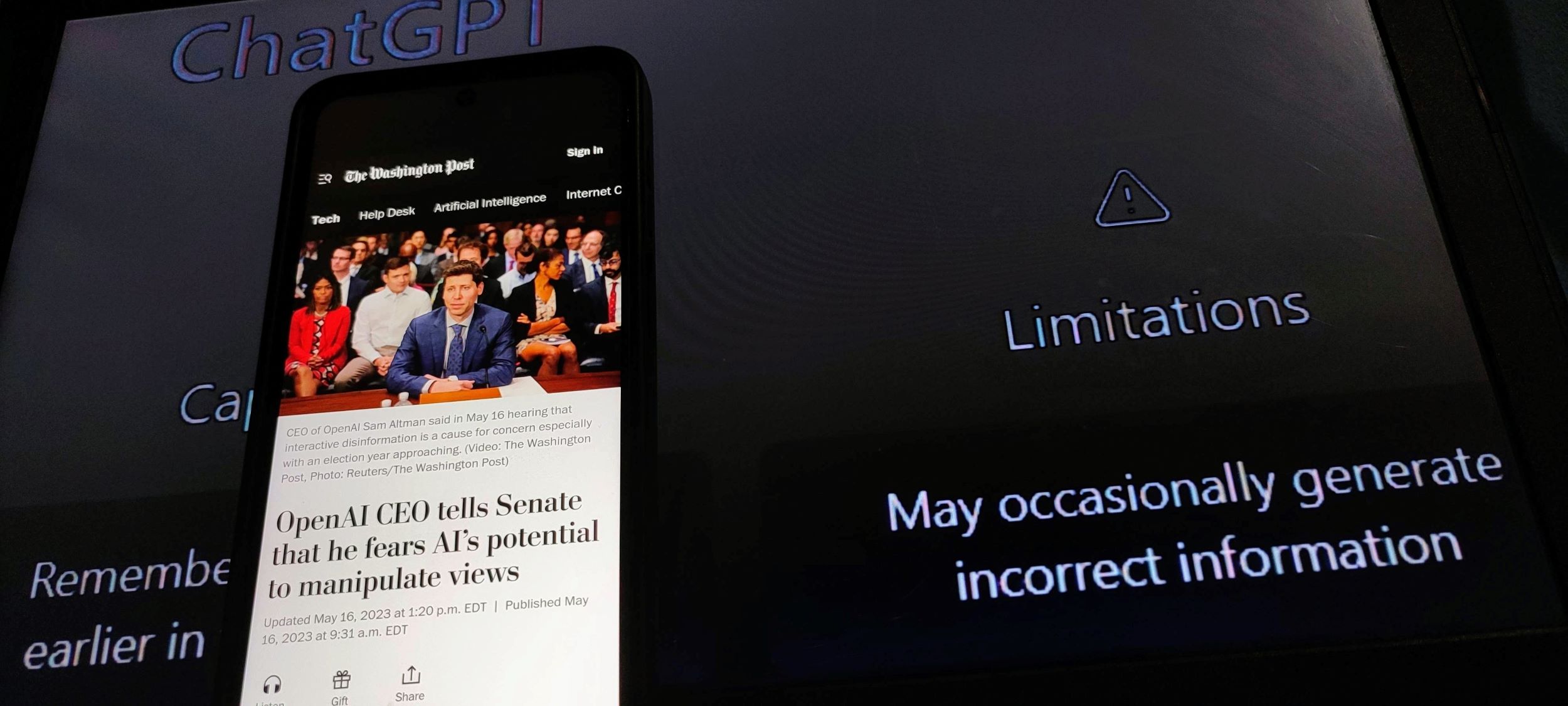

The continued practice of states sponsoring disinformation and dominating media narratives continue to affect trust in traditional media institutions. Further, from the audience’s point of view, the state narrative is not only flawed, but is also meant to actively conceal facts.

This practice of media repression means that audiences will not only confine themselves to media narratives that feed their bias, but also will take measures to ensure their participation in the information sphere remains anonymous.

In times of crisis, foreign interference in the domestic information sphere becomes easier, especially in light of the lack of trust in the state. For instance, during the prince Hamzah debacle, both Twitter and Facebook accounts appeared to have been spreading disinformation.

Here, for example, is a tweet from the “Arab Gulf Information Center,” which appears to be associated with anti-Saudi Arabia rhetoric. The tweet claims, falsely, that there is a “huge financial offer from Saudi Arabia to Jordan to release Bassem Awadallah.” It must be noted that, countering this form of misinformation is not as effective on social media as the misinformation itself, nor does it appeal to the information consumer.

This account has also been active in spreading disinformation, with its tweets being quoted and referenced in many social media posts and WhatsApp messages circulated among the public. The Tweet in question misrepresents the facts and clearly exaggerates the Prince Hamzah controversy in an inflammatory manner.

In the aftermath of the Salt Hospital incident, disinformation also spread quickly over social media. One example in particular shows how manipulated content is spread and meant to incite audiences. A popular WhatsApp Video insinuated that an armed clash between security forces and citizens took place in northern Jordan. However, it was soon proven that the audio was doctored to insert gun shots into the video and doctored by adding the sound of gun shots to fabricate a clash between the two sides..

In the aftermath of the Prince Hamzah affair, local Jordanian newspaper Addustor claimed that 40,000 twitter accounts were established and were targeting Jordan’s social media sphere with messages designed to undermine state stability and security. However, the paper’s report left out the fact that 40,000 inauthentic accounts is not something hard to manage, establish or direct. Today, inauthentic bot activity on social media is infesting the information sphere, offering perpetrators a cheap and effective tool to meddle in other states’ information spheres while allowing a major margin of plausible deniability.

The ultimate effect of an information sphere awash in disinformation is a loss of public trust in state capacity and state narratives. In addition, the tight grip of the state on media freedom means that the public will be more recipient to conspiracy theories, information presented as “exposing the truth,” as well as to inflammatory content.

*Picture: Local Jordanian newspapers all display similar headlines of the king promising justice for the deaths in al-Salt. (Jassar al-Tahat - 19/03/21)