REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK: How it took the collective memories of several generations, painstaking interviews and a determined search through tall grass and prickly plants to recreate a destroyed community

On a Monday in late March, I found myself trapped in a field of tall grass and spiny, prickly plants, despite having faithfully followed the directions on Google Maps to reach the ruins of Bayt Nabala, a Palestinian village destroyed in September 1948 by Israeli forces.

The sun was blazing overhead, my throat was parched and I had been walking in circles for what felt like an eternity, unable to locate any of the landmarks that Bayt Nabala’s former inhabitants had told me about when I spoke to them. “You’ll see what’s left of the main village well, close by is the cemetery, and there’s cacti around it. You can’t miss it,” one of my interviewees had told me confidently.

Believing that it was impossible for me not to be able to find the last vestiges of the village with the aid of modern technology, I had set off from Tel Aviv by public bus, carrying just a canvas bag with a small bottle of water, a book, my phone, a portable charger and all the hubris of someone who has never attempted to search for a place that has been ravaged by time and the Israeli military. Two hours later, the bus deposited me by the side of a busy highway and I began walking down a dirt path towards what Google told me was Bayt Nabala. I was hopelessly lost and already out of water.

This was the penultimate day of my reporting trip to Palestine and Israel. Rather serendipitously, I had been on commission for another longform story in the West Bank, when an editor from Al Jazeera English whom I have worked with several times contacted me and asked if I would be available for an assignment. The plan was to collaborate with the Slow Journalism and Interactive teams on an ambitious project to recreate one of the 530 Palestinian villages that were demolished during the creation of Israel. To commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Nakba, we hoped to launch a project that would intertwine the narratives of survivors and their descendants with artificial intelligence (AI)-generated depictions of their ancestral village.

In one of our early online meetings, I had suggested focusing on Bayt Nabala. I had heard about the village completely by chance while chatting with Muammar Nakhleh, who runs Wattan TV, one of Palestine’s largest independent media stations. He had casually mentioned to me that Ben-Gurion Airport - Israel’s main commuter airport which is notorious for some of the most stringent security checks in the world - had been built over part of the land of his ancestral village.

Everyone on the Al Jazeera team was immediately struck by the significance of Bayt Nabala’s location and how it represents the oppressiveness of the Israeli occupation. 19.2 million passengers travelled through Ben-Gurion last year, but few if any at all were Palestinian, since the latter cannot fly from the airport without special permission from the Israeli authorities. We decided to recreate Bayt Nabala to the best of our abilities.

Our first task, which would fall on my shoulders as I was the only member of the team physically in Palestine, was to identify former inhabitants of the village who still had memories of it, and would be able to tell us how the village used to look. This information would be vital in the making of the AI images. I would interview them first, before speaking to second and third generation villagers - or “Nabalis”, as they often colloquially call themselves. Then, after exiting the West Bank and before flying back from Tel Aviv back to London where I live, I would try to find and photograph whatever was left of Bayt Nabala.

Battling nature

As I struggled to find my way out of the thick vegetation, I tripped and fell multiple times, pricking my fingers on thorns. I thought I was becoming delirious from the heat. One of the most rewarding things about being a journalist is to have your expectations of the reporting process thwarted; you learn that people and places can surprise you and teach you something new. But this isn’t so pleasant when you’re caught off guard by how unprepared you are for the possibilities. Later, I would find out that even descendants of the villagers who left during the Nakba struggled to locate their homes without detailed guidance from relatives.

I ended up being picked up by a young Israeli soldier in a van. He was concerned that instead of heading to Beit Nehemia, the moshav (a type of agricultural community in Israel) that had been built atop Bayt Nabala’s southwestern end, I was walking – in a rather disoriented fashion – towards his camp, which he politely mentioned was most certainly off limits to tourists like myself. Not wanting to reveal I was a journalist and desperate for a brief respite from the unforgiving sun, I meekly accepted a lift from him to a road that led to Beit Nehemia.

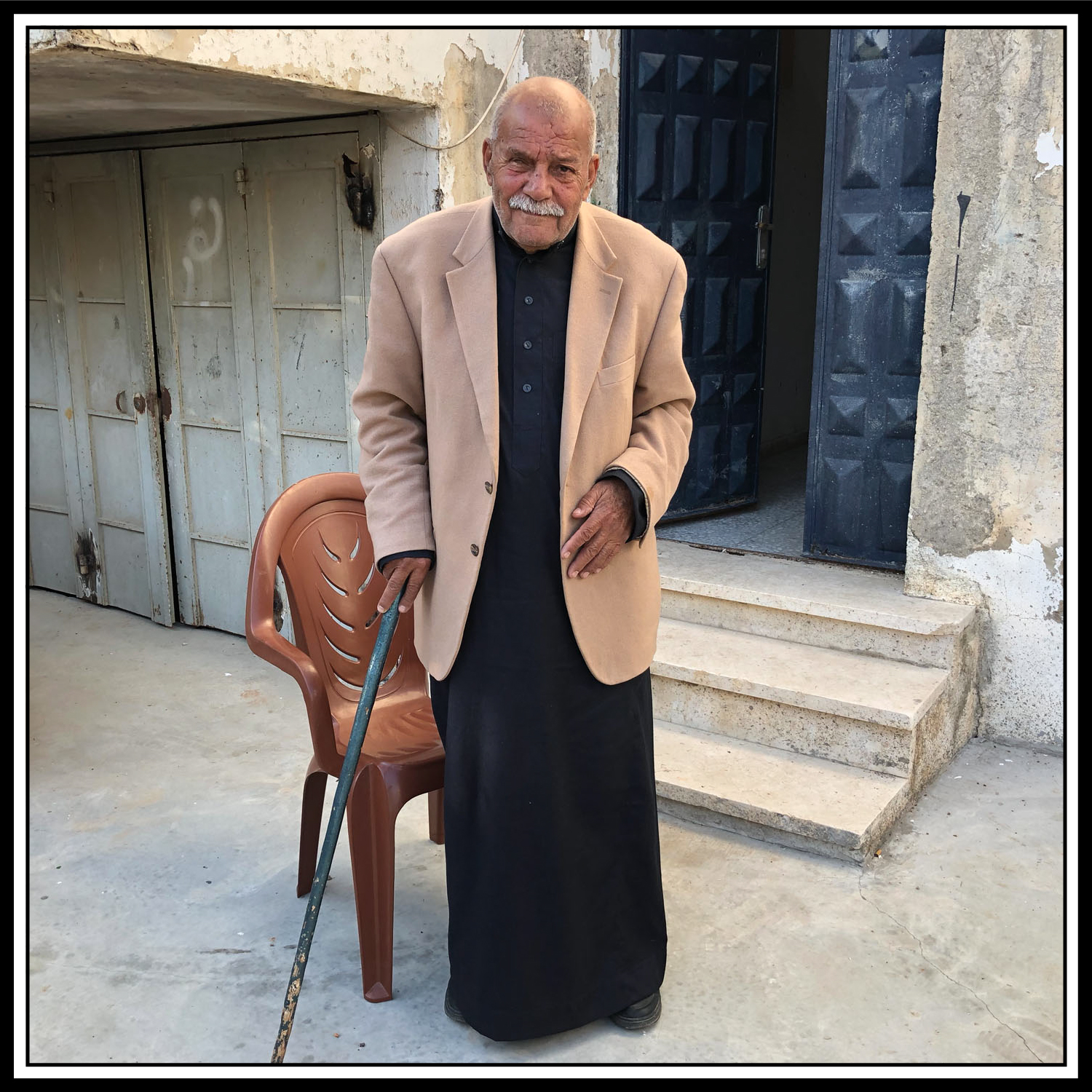

I thought that after multiple conversations with different people from Bayt Nabala, I would have had no trouble finding the village; clearly I had been humbled by the forces of nature. In the two weeks prior, I located, met and spoke to three elderly former residents of Bayt Nabala, all of whom had fled as children with their families in the early days of the Nakba, and had been living in the Deir Ammar and Jalazone refugee camps located close to the de facto Palestinian capital of Ramallah for most of their lives.

I had underestimated how chaotic it would be to interview them in and around their homes: Palestinian refugee camps, built by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) with cinder blocks from 1950 onwards, are extremely cramped spaces with very little privacy. A Palestinian man I met in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp had joked that “in a refugee camp, if you sneeze, your neighbour can hear you”.

Later, as I played back the audio recordings of my interviews, I would be amused by the constant interruptions during the conversations - children walking into the room to chat with the interviewees, cats yowling on the street, cars driving past with their passengers waving at us, the translator pausing the interview to take a call on his phone. Even while talking about their painful experiences of exile, my interviewees in the refugee camps never failed to astound me with their humour, and the ease with which they switched between their quotidian routines in the present and their memories of the past. But these nuances in the conversations were not adequately captured the first time round by my translators because of the hullaballoo in every interview; I had to go through them again with a Palestinian friend who kindly helped to translate. You learn that a patient ear can hear the tenderest of revelations through all the noise.

A ‘collective memory’

Perhaps what fascinated me most about this project was the incremental nature of collective memory - and also how slippery it can be. The first-generation survivors from Bayt Nabala might not, for example, be able to recall the clashes between Zionist invaders and Palestinians in and around the village, but they would reveal in poignant detail vignettes from their childhood: watching the trains go by; trading candy for wheat; picking vegetables in the orchard; running in the valleys around the village and watching the planes land at the airfield in the nearby town of Lydda, which was later expanded 100 times to become Ben-Gurion Airport.

Follow-up interviews with them, conducted by a Palestinian journalist, would elicit in disorientating fragments their recollections of the immediate aftermath of the Nakba. They spent months, even years, sleeping wherever they could - under olive trees, in caves, in the homes of other Palestinians in villages that hadn’t been seized by the Israelis. This is perhaps a forgotten aspect of people’s experiences of the Nakba that I’m very heartened to have been able to capture in the story.

It was the second-generation villagers I spoke to, born just a few years after the Nakba and who are now scattered around the world from Jordan to the US, who filled me in on the rich history of the village. They had, after all, heard so much about Bayt Nabala from their parents, and recognised that life there was worlds apart from the squalor and abject poverty of the refugee camps they had grown up in. From them, I learnt all about the communitarian ethos of the olive harvests, where people made it a point to pick olives from the trees belonging to other families or clans, then sharing what they had harvested with everyone else.

Speaking to the third-generation descendants of Bayt Nabala, I couldn’t help but marvel at the fecundity of their imagination – and how this, in a way, breathed life into the village decades after it no longer physically existed. One of them said that she had spent her whole life conjuring up different possibilities for the lives she could have led had the village not been destroyed. Another had written short stories, dreamlike sequences, about a parallel life in Bayt Nabala, where she could hop on a train to Damascus and travel could take place on a whim, unfettered by hideously long and insulting searches at Israeli checkpoints. All together, my interviewees - of very different dispositions and life experiences - enabled us to create, in over 10,000 words, a patchwork of memories and stories about how life had been like in Bayt Nabala.

It takes a village

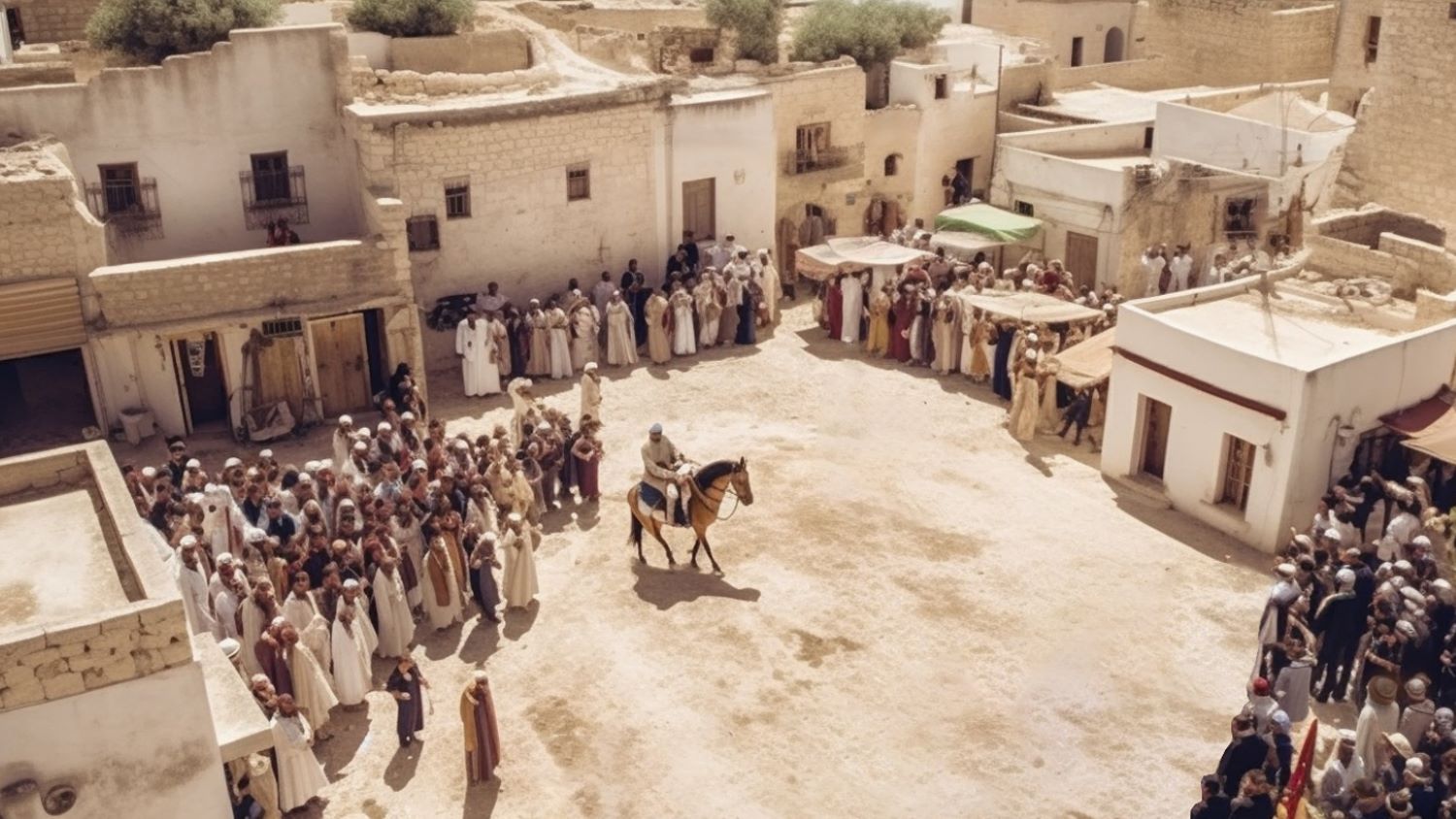

As one of my editors put it so wonderfully, it takes a village to recreate one. Through the panoply of stories that we had collected, along with books, documents and photographs dating back to the period around the Nakba, the interactive team was able to produce an array of AI images that we felt might form an accurate visual representation of Bayt Nabala. We consulted some of our interviewees through this process: did the houses need to be closer together; would homeowners have had a carpet on the floor; how simple did the windows need to be? In the week leading up to the publication of the article, the team worked tirelessly on the feedback of my interviewees to perfect these details. The challenge was how to convey a sense of what the village might have looked like, without these re-creations being mistaken for an exact replica.

Without the AI, I doubt that the story would’ve been as emotionally arresting as it was. When it went live, I sent it to one of my interviewees. She responded, “thank you for taking me home.” It’s comments like these that remind me of why I chose to be a journalist. We may not change the world with the stories we tell, but, in the words of the inimitable Martha Gellhorn: “I have thrown small pebbles into a very large pond, and have no way of knowing whether any pebble caused the slightest ripple. I don’t need to worry about that. My responsibility was the effort.”

Read the result of this investigation and recreation of a Palestinian village by Al Jazeera: 'My village': Destroyed in the Nakba, rebuilt memory by memory