Analysis on the impact of media disinformation on public opinion, particularly during UK riots incited by far-right groups. A look at how sensationalist media can directly influence audience behaviour, as per the Hypodermic Needle Theory, leading to normalised discrimination and violence. The need for responsible journalism is emphasised to prevent such harmful effects.

When words of division and racial discrimination are broadcasted and printed, they echo through society, ultimately, resulting in acts of violence and unrest on the streets.

These headlines and narratives don’t just remain confined to screens or newspapers—they have a broader impact on people’s thoughts and society as a whole. They infuse into the public consciousness, gradually altering perceptions and deepening biases, beyond just the media format they are presented in.

The Hypodermic Needle Theory in Media

According to the Hypodermic Needle Theory, which studies media effects on behaviour, the media has a direct and powerful influence on audiences, like being injected with a needle just under the skin.

Metaphorically, just as an iron infusion affects physical health and bodily functions, media messages can shape, fill, and adjust mental and social perceptions, influencing how people understand and react to the world. This theory assumes that audiences are passive recipients who will "accept" and "act" on whatever they see or are exposed to without questioning it.

The process is simple: Sensational headlines and provocative language stir up fear and anger. As these emotions grow, social bonds weaken and create a breeding ground for conflict. Constant exposure to divisive rhetoric makes discriminatory attitudes seem normal and acceptable.

In this toxic atmosphere, individuals and groups who might have previously held hidden prejudices feel encouraged to act on their worst behaviours. This creates a dangerous situation, where media-fueled hostility spills over into real-world actions—hate speech turns into hate crimes, and social divisions turn into violent confrontations.

UK Riots and Rhetoric Building Over the Years

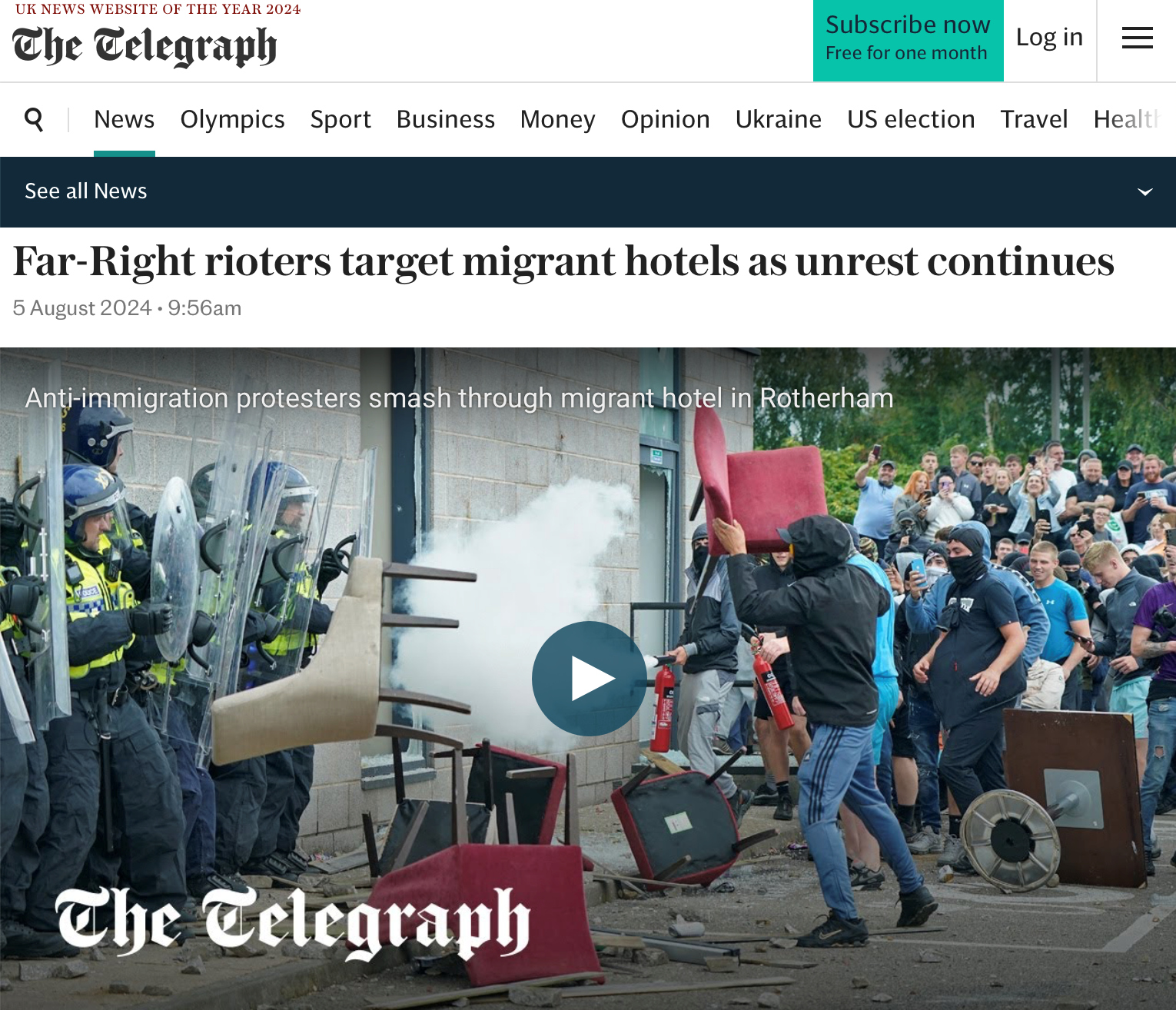

The recent racist riots in the United Kingdom, driven by far-right groups and fueled by the erroneous identification of a 17-year-old stabbing suspect as a Muslim immigrant, illustrate this theory in action. The violent attacks by far-right rioters on hotels housing asylum seekers can be seen as a direct outcome of years of divisive, xenophobic media coverage and misinformation.

Take, for instance, this 2015 front-page headline from the British tabloid The Daily Mail: "Migrants: How Many More Can We Take?" [IMAGE 1] The wording and tone are designed to evoke a sense of crisis and urgency. The phrases "how many more" and "can we take" suggest that migrants are a burden and a threat to society, indicating that their presence is harmful to the native population. The use of "we" positions the readers as part of an embattled group, creating a shared sense of anxiety and resistance against migrants, portraying them as problems rather than individuals seeking refuge or contributing to society.

Other Daily Mail headlines, such as: "True Toll of Mass Migration on UK Life: Half of Britons suffer under strain placed on schools, police, NHS and housing" (2013), and "The Swarm on Our Streets" (2015) [IMAGE 2], further dehumanise migrants. Referring to them in terms such as "swarm," "toll," and "mass" strips away individuality and paints them as a monolithic threat. The headline: "4 out of 5 migrants aren’t Syrians" (2015), questions the legitimacy of migrants' claims, suggesting most are not genuine refugees. Similarly, "Free hotel rooms for the Calais stowaways" (2015), criminalises migrants by implying they are unfairly receiving aid.

This ongoing portrayal of migrants as problematic or threatening contributes to a climate of intolerance and hostility. This, in turn, shapes political discourse and policy-making, often leading to stricter immigration laws and increased societal divisions.

Another prominent British tabloid, The Daily Express, has also published provocative headlines in past years. For example, the 2005 headline: "Bombers Are All Spongeing Asylum Seekers" [IMAGE 3] suggests that asylum seekers are not only a financial burden but also a security threat. The word "spongeing" makes it sound like they are taking advantage of the system, while "bombers" makes them as dangerous.

This continuous stream of divisive media narratives has perhaps set the stage for violence and unrest in the UK, illustrating how media-fueled hostility can escalate into aggression.

Zarah Sultana, MP for Coventry South, recently highlighted the issue. On August 5, Sultana appeared on ITV’s Good Morning Britain and discussed how Islamophobia is fueling riots in several UK cities. Sultana criticised media outlets like the Daily Mail for their biased reporting, which normalises Islamophobic and anti-migrant sentiments. She posted a collage of the Daily Mail headlines on X to illustrate her point:

Writing on X, she also said: "The sneering contempt of ‘journalists’ will never stop me from calling out racism and Islamophobic hate."

Examples of Islamophobic Headlines

This included headlines like: "UK Muslims helping jihadis," through which the Daily Mail portrays many Muslims in Britain as involved in terrorism, provoking fear and outrage.

Another troubling Islamophobic headline from the past years by The Daily Express: "Muslim School Bans Our Culture" (2009), frames Muslims as a threat to British identity, creating a divisive "us versus them" narrative.

In 2015, The Sun ran the headline "1 in 5 Brit Muslims' Sympathy for Jihadis," distorting poll data to suggest widespread support for terrorism among British Muslims. Thereby, unfairly stigmatising the entire community by suggesting that one in five Muslims holds extremist views.

The recent attack on a mosque by far-right rioters during the UK riots highlights how Islamophobic media coverage can incite violence against both individuals and symbols associated with targeted communities.

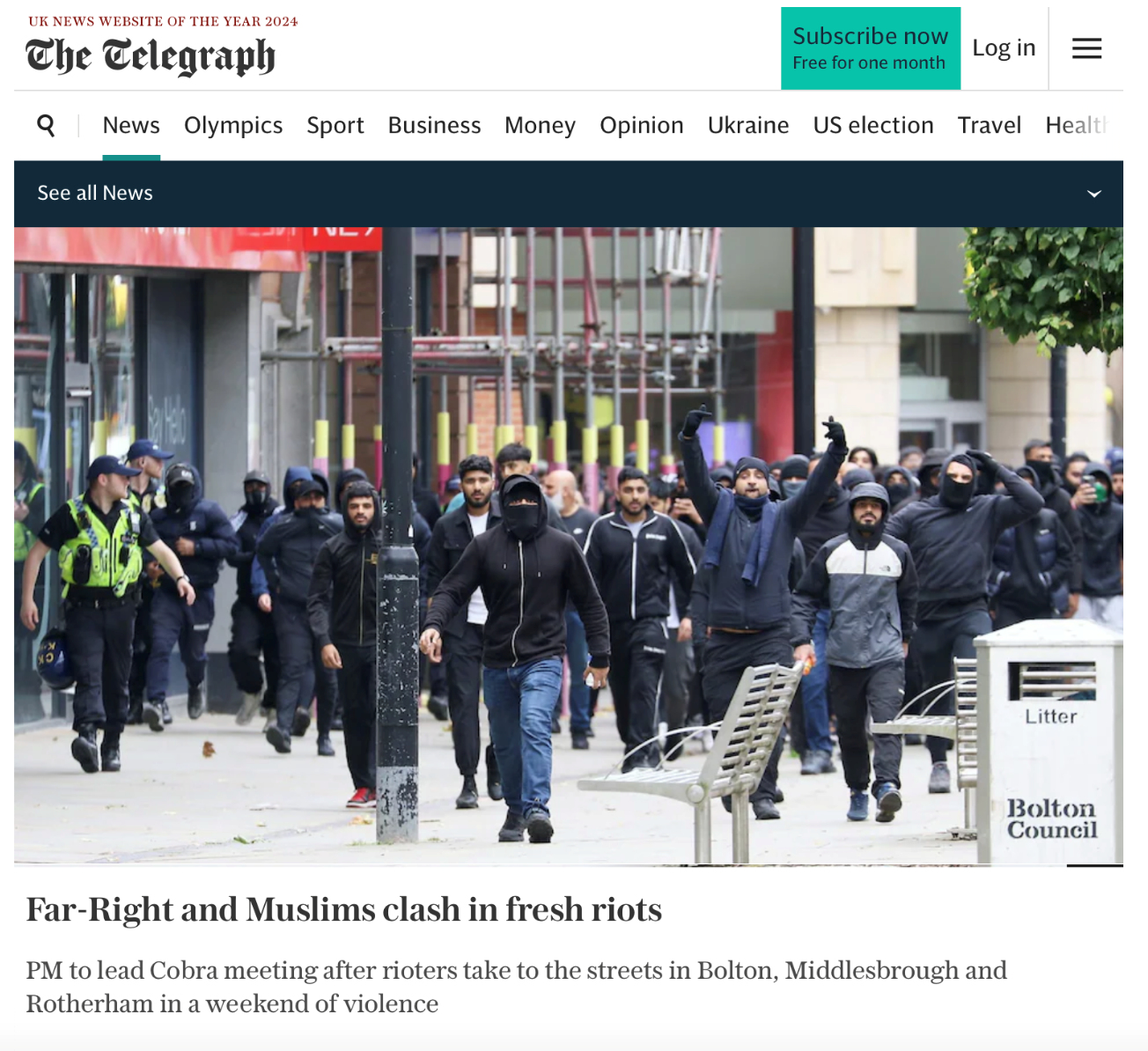

Current media coverage also reflects this pattern, as seen in The Telegraph's headline: "Masked Muslims ‘stand guard’ at mosques," which uses unsettling language to suggest secrecy and threat. The term "masked" implies concealment, casting Muslims in a defensive, militant light. By using "stand guard," the headline portrays the Muslims’ actions as a response to perceived threats, rather than as protective measures or community efforts. The use of verbs like "protect" or "secure" would have instead conveyed a less alarming intent. Inside the article, the Muslim men involved are described through their attire, using terms such as "balaclavas," and references of them carrying Palestinian flags and chanting of religious phrases.

However, in contrast, The Telegraph’s coverage of far-right protesters presents a different narrative. The headline: "Far-Right Rioters Target Migrant Hotels," focuses solely on their criminal behaviour without mentioning religious or ethnic identifiers. Although the article does describe the "rioters" as "masked and hooded," such terms are absent from the headline.

Similarly, The Telegraph headline: "Far-Right and Muslims Clash in Fresh Riots,” simplifies the situation by framing it as a direct confrontation between two opposing groups, emphasising violence over underlying issues. Whereas the term "fresh riots" suggests that this event is part of an ongoing series of disturbances, hinting that the situation may continue and leading readers to view these incidents as part of a broader, unresolvable conflict between communities.

These contrasts demonstrate how media language and emphasis shape the interpretation of events and influence audience perception.

A Historical Case

Sensationalist coverage of protests and riots, often with racial bias, has been evident for decades. For example, the Watts Riots of 1965, triggered by the arrest of Marquette Frye, a Black man, were covered in a way that highlighted deep-seated racial inequalities. The Los Angeles Times used inflammatory headlines like: "You're black and that's all there is to it!" and "Negro riots rage on."

From the LA Times archives: Aug. 15, 1965: Negro Riots Rage On; Death Toll 25. Aug. 15, 1965

Political Figures and Media Influence

The United States, like the United Kingdom, is similar in its biassed media coverage. Take, for example, the headline: "I think Islam hates us: A timeline of Trump’s comments about Islam and Muslims" (May 20, 2017), by The Washington Post, which appears to be a deliberate choice of quote. Highlighting this particularly charged statement rather than selecting a less provocative comment draws attention and engagement. This approach reinforces the perception of prevalent anti-Muslim rhetoric among political figures.

This is also illustrated by the political figure Nigel Farage, known for his role in leading the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and later the Brexit Party in the UK. For example, the headline by The Daily Mail: "Nigel Farage says Tories have 'betrayed' Britain and claims UK should have 'zero' net migration," draws attention to his controversial immigration views, which have been central to his political identity.

Similarly, in Europe, anti-migrant narratives persist. Last year, a headline from Germany's Bild newspaper: "BILD-Manifesto: Germany, we have a problem!," frames migrants as a pressing issue for the country. The accompanying 50-point manifesto inside the article, which demands that migrants learn German, respect local customs, and uphold democratic values, reinforces a narrative of assimilation over multiculturalism. This authoritative and directive language positions migrants as outsiders who must conform to the dominant culture to be accepted.

The Ripple Effect: How Irresponsible Journalism Fuels Violence

This kind of journalism spreads hate and weakens social cohesion, making violent reactions more likely. As the public absorbs these repeated messages, prejudices become normalised, and the threshold for expressing and acting on them lowers, culminating in the violent outbursts we witness today.

It highlights the dangerous and irresponsible power of such narratives, demonstrating that what begins as exaggerated headlines and fear-mongering stories can escalate into tangible, harmful actions. Addressing these issues requires media literacy, critical consumption of news by the public, and a commitment to responsible journalism that upholds ethical standards and fosters social harmony.