The welfare of African journalists is steadily worsening, with issues ranging from poor wages to security threats, arrests, detention, and even death. These persistent challenges not only endanger their lives but also impact the quality of their work as they struggle to perform their duties under increasingly difficult conditions.

Ruot George W. Mut, a journalist and human rights activist from Juba, South Sudan, has spent most of his career working in conflict zones. In December 2009, he began working for state radio, providing civic education. Despite the ongoing war, he persevered, even as his job often put his life at risk. In his account to Al Jazeera Journalism Review, Mut's experiences reflect the daily realities faced by many African journalists.

“I started working in the media in 2009, first by providing civic education to the public, working for a government radio station, as the country was going towards general elections in 2010, after 21 years of war, leading to the split into two countries in 2011,” said Mut. “The civic space in my country is shrinking as we head towards elections. It is more common to carry a gun rather than a camera.”

Like Mut, many African journalists face a constant struggle, dealing with increasing security risks, poor remuneration and less recognition for the work they do. In their daily lives to inform the public, they may appear famous, but they struggle to make ends meet, risking their lives and families to speak truth to power, yet their reward, social and financial status, remains a pittance. Some even die as paupers, with their vast contributions to the media industry and the communities at large, suddenly forgotten.

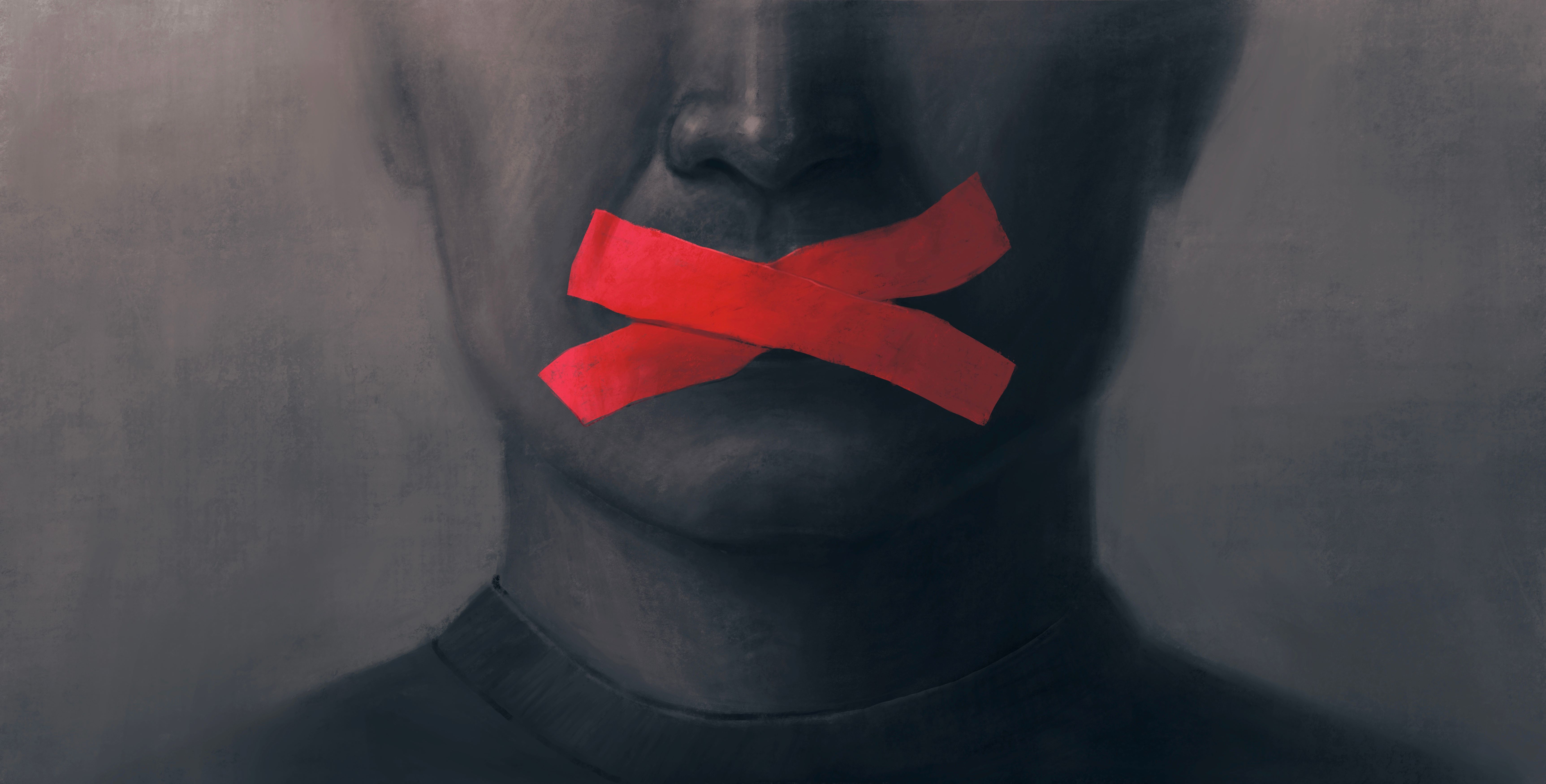

Hostile Environment

Media professionals in South Sudan, the journalist and human rights activist admits, continue operating in a risky environment due to the hostile working conditions, which are constantly displayed towards them by the authorities. “In South Sudan, it is normal to move around with a gun rather than a camera. People in the media are considered enemies of the state by the authorities; we are often misunderstood as enemies of the state and agencies of the west,” said Mut.

Josephine Chinele, a Malawian investigative journalist, has also faced significant threats, often being forced to abandon projects due to security concerns and the lack of protection for journalists. “As an investigative journalist, I face some security issues; sometimes you literally have to drop a story because you will not be protected, so your life could be at risk,” she told Al Jazeera Journalism Review. “I have to choose between pursuing a story or ensuring my safety, and often I opt for safety.”

The hostility towards journalists is rising across the African continent, from stringent legislation to arbitrary arrests and jailings of journalists for no apparent reason, further narrowing their space and endangering press freedom. The daily work of African journalists is becoming increasingly perilous, not only for themselves but also for their families.

“Threats to the right to freedom of expression and the media continued unabated across the East and Southern Africa region over the past year,” said Tigere Chagutah, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East and Southern Africa. “Speaking out against or scrutinising government policies, actions or inaction, or publicly sharing information deemed damaging to the government carried the risk of arrest, arbitrary detention, or death.”

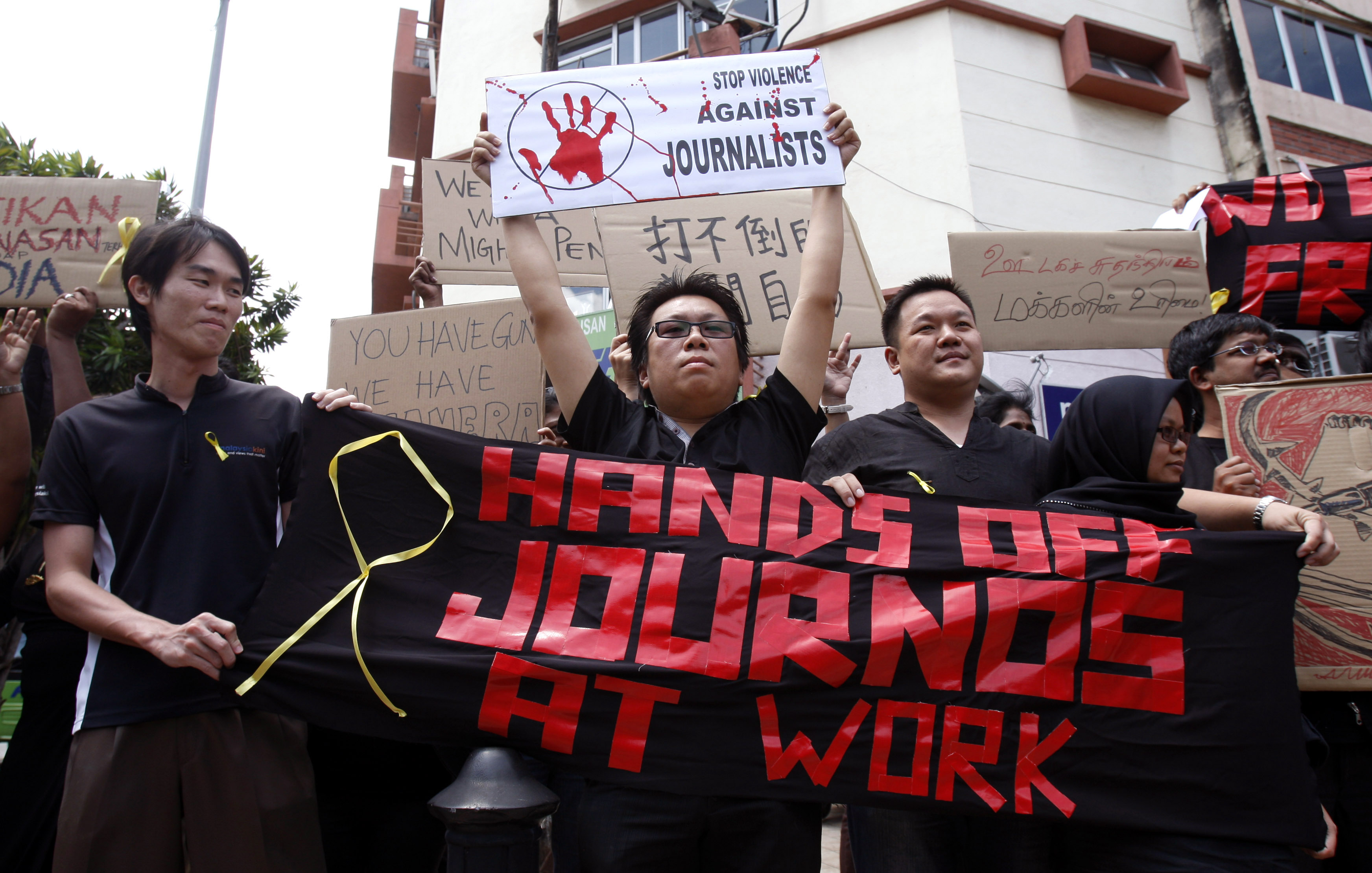

Harassment on the Rise, Is Journalism worth the Risk?

Cases of harassment and threats against journalists are on the rise across Africa. Burundian journalist Floriane Irangabiye was recently released, two years after being sentenced to ten years in jail for ‘endangering the integrity of the national territory.’ In 2023, an anti-corruption campaigner and journalist, Arsene Mbani Zogo, aka "Martinez,” was abducted in front of a police station, tortured and killed. In Guinea-Bissau, two journalists, Djuma Culubali and Ngouisam Casimiro Monteiro, were attacked by the Rapid Intervention Police while they reported a teachers’ protest on 31 July.

Chadian journalist Badour Oumar Ali was released 24 hours later, following his abduction by hooded armed men on 7 August, after the publisher refused to take down articles written about a former presidential adviser. Gregory Gondwe, a Malawian investigative journalist, went into hiding, fearing for his life, after exposing corruption within the military. Senegalese newspapers and radio stations recently embarked on a national blackout to protest threats to press freedom.

On September 9, a few days before this article was published, Mut was arrested following a defamation case filed by the Union of Journalists of Southern Sudan (UJOSS). This comes after his suspension as the Programmes Coordinator of over contractual disagreements and what he calls misallocation of donor funds within the union, according to two documents he shared. Responding to his arrest, he told Al Jazeera Journalism Review that, “There are some people who want to use the journalists’ protection and welfare funds to silence my voice as I call for adherence to the rule of law in the media. I have never heard a journalist arrest another journalist.”

In a letter dated September 10, the UJOSS management defended the arrest, saying, “This was done in September 2024 to compel Mr. Ruot to produce evidence regarding what he has been alleging, such as UJOSS leaders being “corrupt, members of a criminal group, military, and cartel.” Due process was followed, an arrest warrant was issued, and Mr. Ruot’s arrest was affected.”

Election periods often bring heightened threats and violence against journalists in Africa. “Elections in sub-Saharan Africa resulted in a great deal of violence against journalists and the media by political actors and their supporters. This was evident in Nigeria (ranked 112th in the 2024 World Press Freedom Index), where nearly 20 reporters were attacked in early 2023,” said Reporters Without Borders (RSF). “During elections, politicians also try to use the media to exert influence and impose authority.”

Integrity or Life at Risk

Without proper union representation for journalists in Malawi and Africa, the integrity of journalists and work output is largely compromised. “Media watchdog institutions in Malawi are less proactive, and as a result, the profession faces a number of challenges, such as the infiltration of fake journalists who attend events merely for free meals,” said Kondwani Magombo, 49, a Malawian journalist. “Salaries are generally too low to sustain the needs of a journalist, and this creates a conducive environment for corruption among journalists and sources.”

Magombo, who earns around $290 in a good month, both as a full-time reporter and a freelancer, says this is not enough to sustain his work and family. This grim situation is common for African journalists, affecting the majority of professionals. “There are several challenges, but key ones are lack of employment. The country’s colleges and universities are releasing hundreds of well-trained journalists into the job market with few employers to absorb them,” Magombo said.

Mut says, for the first years, his income was regular; then, he used to make a decent living, but suddenly, when the country split, things fell apart for the gangling journalist. “Payment is another biggest challenge; we don’t have a decent pay as journalists. Before, I contributed to international media organisations and made a decent, regular income. When there was insecurity, leading to war in 2013, I stopped and started freelancing, and I now get US$100-500 per month. I also work as a translator for local languages, but that is not steady work,” he explained.

Resilience in Tough Times

Bribes, often referred to as “brown envelopes,” are becoming a threat to journalistic ethics as poor remuneration, lack of health insurance, and the absence of pensions push some journalists to abandon their principles. The current hardships—non-payment and a non-functional media across Africa—remain the biggest threats, but according to Chinele, having a side hustle is another way to financially empower journalist, besides an erratic income. The resilience of African journalists is worth celebrating, said Omar Faruk Osman, the President of the Federation of African Journalists (FAJ), during the 2024 World Press Freedom Day.

"Today, as we celebrate the resilience and dedication of journalists across Africa, we must also confront the harsh realities they face—low pay, long hours, threats and dangerous attacks, particularly in environmental reporting,” said Osman. “This untenable situation must change if journalists are to continue as key forces for environmental justice. We urgently need to enhance their working conditions, striving towards a future where journalists are both safe and supported in their essential roles."

To safeguard the profession, Mut is now advocating for better conditions for media professionals in his country as a union leader. “From 2021 until my suspension in 2023, I was working in media leadership, working as the Programme Coordinator, with UJOSS, where we were formulating policies on welfare, protection and professionalism, helping many journalists avoid conflict with the authorities and improve their work, so they deliver professionally.”