Experts in Africa are using various digital media tools to raise awareness and combat the increasing usage of misinformation and disinformation to manipulate social governance.

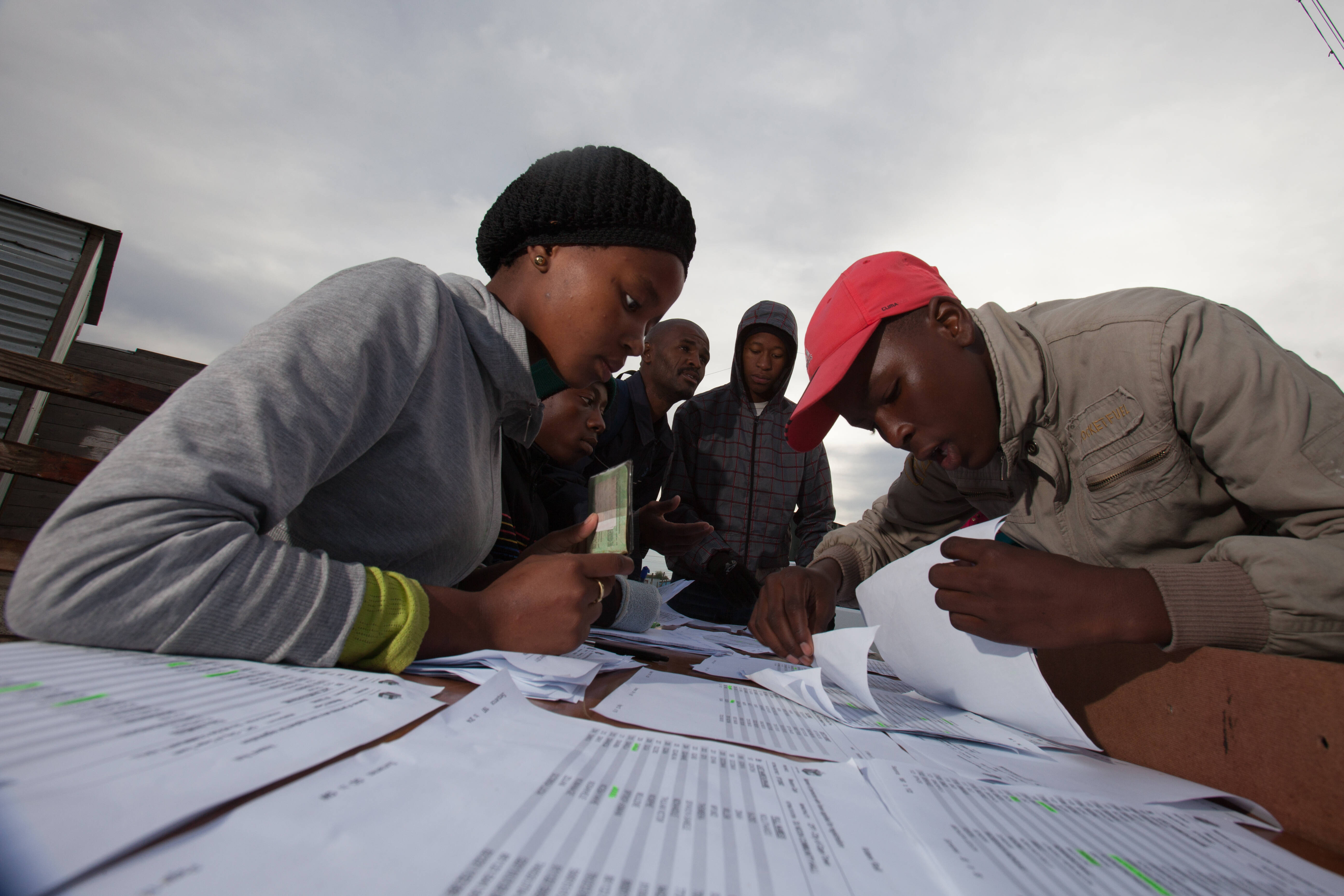

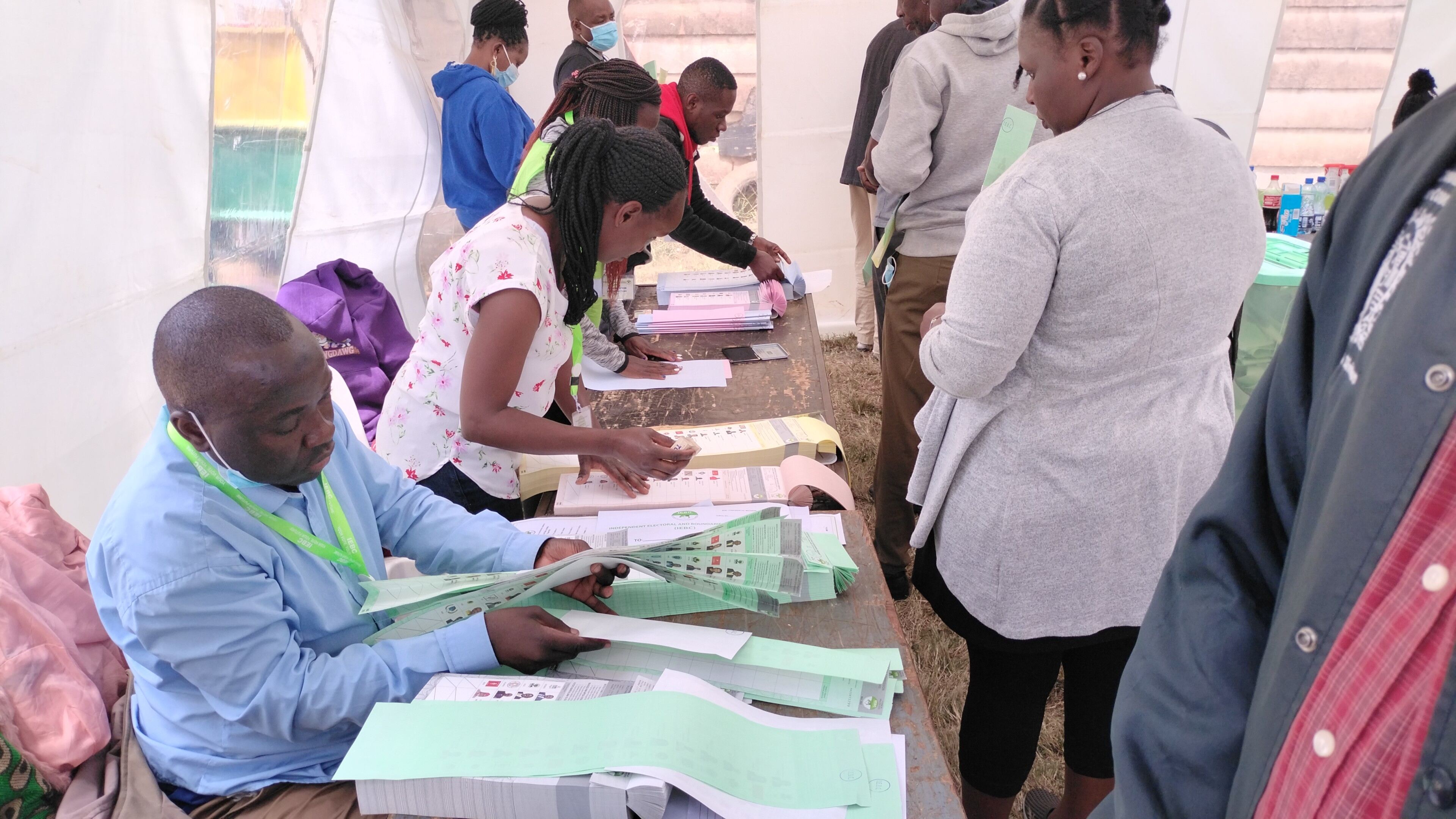

This year, 2024 has been dubbed an election year, with almost 20 African nations, and nearly 180 million eligible voters set to go, or have already conducted polls, and already, some nations have noted an influx of misinformation and disinformation, in a bid to win the electorate, fight competitors, deliberately confuse, or lure voters.

Misinformation is false information, often regarded as fact, even though it might not be intended to deceive, while disinformation is the opposite, with direct intent to deceive, using false information, meant to push a certain political agenda.

Africa, with over 384 million social media users as of 2022, and around 570 million internet users in 2022, plus the proliferation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has recorded widespread misinformation and disinformation campaigns within the continent, with powerful politicians, governments and even prominent media organisations spending millions to deliberately misinform citizens, for a certain desired outcome.

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies mapped that, “Disinformation campaigns seeking to manipulate African information systems have surged nearly fourfold since 2022, triggering destabilizing and antidemocratic consequences,” it said. “The 189 documented disinformation campaigns in Africa are nearly quadruple the number reported in 2022. Given the opaque nature of disinformation, this figure is surely an undercount.”

Interestingly, almost 60% of the disinformation campaigns in Africa, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies reveals, originate primarily from Russia, China, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, targeting at least 39 African countries.

To counter the spread of misinformation and disinformation, some media organisations, journalists and independent fact-checking organisations in Africa are diligently fighting the spread of wrong, harmful information and propaganda. Using limited resources and personnel, these truth diggers are employing various digital tools to try and preserve the tenets of social governance and foster informed voter decisions, and access to accurate information.

Disinformation campaigns seeking to manipulate African information systems have surged nearly fourfold since 2022, triggering destabilizing and antidemocratic consequences

MISA Zimbabwe’s Guide to Fact-Checking and Information Verification to capacitate the public in fighting against “fake news,” defines fact-checking as “a set of practices and tools that allow you to verify information. It is the process of investigating an issue to verify the facts.” The types of content that can be fact-checked, include photos, videos, and rumours shared on social.

Disinformation tactics

Gifty Tracy Aminu, a fact-checker from Ghana, holding elections later in December, has seen the rise of disinformation, in politics, governance and public health. “When it comes to elections, some of the common disinformation tactics they use is to bring out old videos, or old content, especially,” she said. “On the morning of elections, two or three hours before the elections, you see someone posting videos of how someone has snatched ballot boxes, or someone has raided an election centre.”

Existing, credible media platforms have not been spared by disinformation purveyors, riding on their popularity and large following to imitate their genuine operations and flare to deceive the unassuming public.

“Ahead of our elections in December, those sharing disinformation have started mimicking existing media platforms,” said Aminu. “They don’t have websites, maybe one or two have, but most of them are on social media, and start producing flyers that look like an existing media platform, using the same colour, designs, formats, and similar features that credible media organisations in Ghana use. They then tweak existing information to serve their purpose, or create utterly wrong information.”

What's even disturbing is that the mainstream media is also involved in disinformation to serve their own interest as most are aligned with a certain political party.

Lesotho, without a local fact-checking platform until this January, the proliferation of disinformation is rampant, reveals Palesa Maharasoa, a fact-checker. “In Lesotho, we only have one fact-checking platform which began operating in January this year, so we are literally struggling to fight disinformation,” she said. “What's even disturbing is that the mainstream media is also involved in disinformation to serve their own interest as most are aligned with a certain political party.”

Although some problems exist, Maharasoa and her team are inroads, unearthing some of the common disinformation tactics being used. “In Lesotho, they use smear campaigns amongst different political parties, the use of political party members in the media, especially radio to discredit other parties, and on social media to make unfounded allegations, both against political parties or certain individuals, mainly using historical events.”

The use of media houses for disinformation campaigns cuts across Ghana and Lesotho, with young political activists, trained to speak on issues, sharing false, misleading, or exaggerated information, what they call group influence operations, from people sharing the same political ideology.

Impersonation of prominent figures on social media is also common, meant to deceive those who don’t read beyond, or the less inquisitive. Through studying behaviour actions, Aminu adds, they can establish if they are bots or a group of actors sharing particular similar information, and establish its virality, before they debunk it.

The effects of disinformation cuts deep, especially when it targets the public system and the populace. Let’s take health for example, during COVID-19, disinformation was coming from everywhere, Africa and even Europe, which led to loss of lives. Imagine during elections, where tensions are high.

The effects of disinformation

A recent study on vaccines and infertility fake news online in Africa, showed that “Fake news is a worldwide concern carrying grave political and social consequences,” and is related to “worse mental health outcomes, the misallocation of resources, lower compliance with health authorities & regulations, and increases in vaccine hesitancy.”

This, according to Aminu, was also witnessed in Ghana as well, during the recent COVID-19 pandemic. “The effects of disinformation cuts deep, especially when it targets the public system and the populace. Let’s take health for example, during COVID-19, disinformation was coming from everywhere, Africa and even Europe, which led to loss of lives. Imagine during elections, where tensions are high.”

She added, “Disinformation can undermine our public system, from health to education, to security, to governance, politics, everything, disinformation can cause havoc. It is dangerous, it can lead to death, it can destabilise the security of the country, and the credibility of the public system that the populace strives on.”

Disinformation, Maharasoa noted, “Can mislead the electorate, especially the elderly, and some governments may fail to see their political tenure through, they may be overthrown from power, within a short period. It may lead to an unstable, politicised and poor public service and an unstable economy.”

Can fact-checking preserve democracy?

Generally, in Africa, the trust for the electoral management bodies to act independently, and hold, free, fair and credible elections has been diminishing. Old parties, seeking to unsettle new players and entrench their reign, may result in disinformation campaigns trickling in. The prevalence of weaker, partisan public institutions, such as electoral bodies, security apparatus, and the judiciary, will only help intensify the existing problem.

“The polarisation, differences in ideology, partisan interest and existing beliefs, that in Africa, ruling parties are always supported by electoral bodies, and they have more machinery to rig the elections,” said Aminu. “As we go into the December election, the opposition believes that the electoral body is in bed with the ruling party, so it is possibly going to fabricate stories that are not true to tarnish and undermine the electoral process. We have also seen AI-generated videos playing pivotal roles, people saying something dangerous to our democracy.”

From Aminu’s experience, despite the good work, fact-checking remains a tedious job that requires more participation and resources, however, despite this, it is helping to strengthen democracy in Africa.

The MISA Zimbabwe’s guide says, “Factual information will help news audiences effectively make decisions on pertinent issues. For example, during elections, the electorate needs accurate information to make informed decisions. Facts help us understand a country’s most complex economic and social problems. Facts have the potential to minimise the impact of information disorders.”