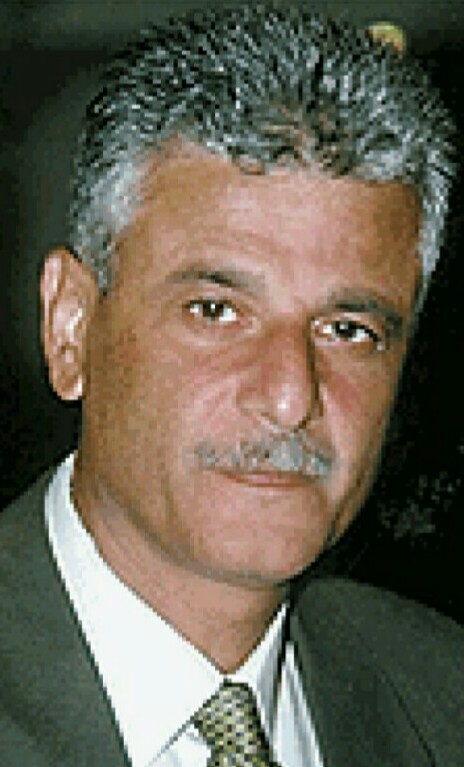

On September 30, 2000, a Palestinian cameraman from Gaza, Talal Abu Rahma, shot a video of a father and his 12-year-old son under fire on the Saladin Road, south of Gaza City. The boy, Muhammad al-Durrah, was mortally wounded and died soon after.

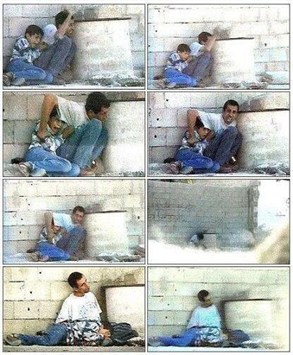

The video of Jamal al-Durrah trying to shield his son as bullets rained down on them was aired by France 2, the news channel Abu Rahma was working for. It became one of the most powerful images of the Second Intifada.

The Israeli government tried to challenge the veracity of the video, with the Israeli military denying that its soldiers had been responsible.

It took until 2013 for a French court to vindicate France 2 and Abu Rahma, ultimately upholding their defamation case against Philippe Karsenty, a French media commentator who had accused them of staging the video, and fining him 7,000 euros.

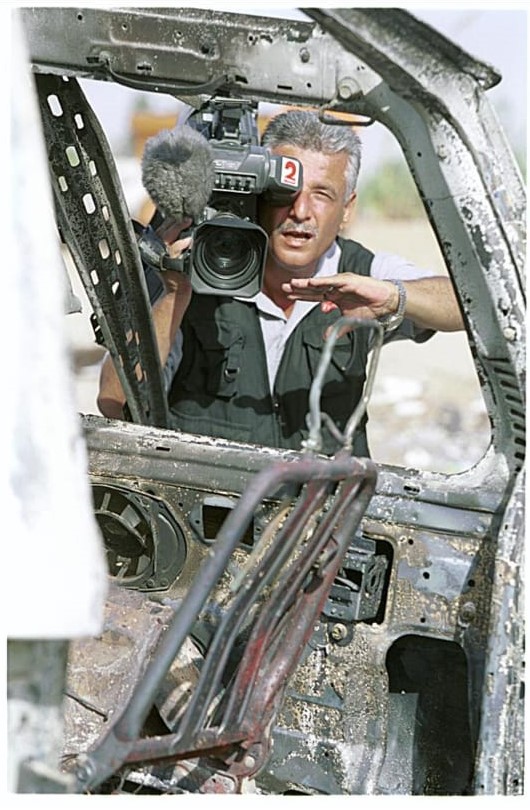

Abu Rahma, who has won numerous awards for his work, including the Rory Peck Award in 2001, is now based in Greece, where he, his wife and eight-year-old son are residents. He works between there and Amman, Jordan. He has been banned from returning to Gaza since 2017.

Two decades later, in an exclusive interview with Al Jazeera in 2020, he recalled the events of that day:

The day before, I was in Jerusalem working at the France 2 office. Charles Enderlin, the France 2 bureau chief in Jerusalem, called me at 10am and said “I am sending you the car, you have to go back quickly to Gaza because the situation in the West Bank is getting very, very bad.”

So I went back. Charles called me when I arrived and asked about the situation in Gaza. I said: “Gaza, it’s quiet, nothing in Gaza.” “OK,” he replied, “well keep your eyes on it, if anything happens, just let me know and go and film.”

At 3pm, 4pm, there was nothing happening. It was a Friday, you know. The West Bank was on fire, but Gaza was really quiet. I knew why it was quiet – because the schools were closed and it was the holy day.

We were watching the situation and I knew, as a journalist, that on Saturday morning there would be a demonstration in Gaza. At that time there were three very sensitive points in Gaza – one at Erez, one north of Gaza City, and the third in the middle, on Saladin Road.

Many people have asked why I went to Saladin Road. It was because it was in the middle. If something happened in Erez or elsewhere I could quickly move there. Like me, all the journalists knew what would happen on Saturday morning. I went down at about 7am because that is the time the students go to school and I knew there would be lots of people around.

They started throwing stones. And hour by hour it increased. I was in contact with my colleagues at Erez, to know what was going on over there – as that was the real hot point.

I stayed where I was until about 1pm. At this point it was tear gas, it was rubber bullets, it was stone-throwing; you know, it was normal. But there were a lot of people throwing stones. Not hundreds. Thousands.

I called the office and told them that about 40 people had been injured by rubber bullets and tear gas. Charles told me “OK, try to make interviews and send it in by satellite.”

‘It was raining bullets’

As I was conducting my second interview, the shooting started. I took my camera off its stand and put it on my shoulder. I started moving left and right to see who was shooting – shooting like crazy. Who was shooting at whom and why, I really didn’t know. I tried to hide myself because there were a lot of bullets flying around.

There was a van to my left, so I hid behind it. Then a few children came and hid there, too. At that point, I hadn’t seen the man and the boy. Ambulances were arriving and taking the injured away.

I could not hear anybody over the sound of the bullets. It just kept getting worse. There was a lot of shooting, many injured. I was really scared. There was blood on the ground. People were running, falling down; they didn’t know where the bullets were coming from, they were just trying to hide. I was confused about what to do to – whether to continue filming or to run away. But I’m a stubborn journalist.

At that moment, Charles called and asked me, “Talal, do you have your helmet on, do you have your jacket on?” Because he knows me, I don’t put the helmet and flak jacket on – it’s too heavy. But he was screaming at me, “Put it on, please, Talal.” I got really mad because I didn’t want to hear it. I told him, “I am in danger. Please, Charles, if something happens to me, take care of my family.” Then I hung up the phone.

In that moment, I was thinking about my family: about my girls, about my boy, about my wife, and about myself. I could smell death. Every second I was checking myself to see if I had been injured.

Then one of the children who was hiding beside me said: “They are shooting at them.” I asked: “Shooting at who?” That was when I saw the man and the boy against the wall. They were hiding and the man was moving his hand and saying something. The bullets were coming right at them. But I couldn’t tell where they were coming from.

Screen shots from the video footage of Jamal al-Durrah and his 12-year-old son, Muhammad, under fire from Israeli forces, taken in Gaza, September 30, 2000. [Courtesy of Talal Abu Rahma]

In the corner on the right side of the man, there were Israeli soldiers and Palestinian security forces. In front of that point was the Israeli base. What could I do? I couldn’t cross the street. It was too busy and very wide, and the shooting was like rain. I couldn’t do anything.

The children beside me were scared and screaming and, in that moment, I saw through my camera that the boy had been injured. Then the man was injured, but he was still waving and shouting, asking for help, asking for the shooting to stop. The boys with me were really going crazy. I was trying to calm them down. I was scared about taking care of myself and them. But I had to film. This is my career. This is my work. I was not there just to take care of myself. There is a rule: a picture is not more valuable than a life. But, believe me, I tried to protect myself and I tried to save this boy and the father, but the shooting was too much.

It was too dangerous to cross the street. It was raining bullets. Then, I heard a boom and the picture was filled with white smoke.

Before the boom, the boy was alive but injured. I think the first injury was to his leg. But after the smoke moved, the next time I saw the boy, he was laying down on his father’s lap and his father was against the wall, not moving. The boy was bleeding from his stomach.

The ambulances tried to get in many times. I saw them. But they couldn’t because it was too dangerous. Eventually, one ambulance came in and picked up the boy and the man. I whistled to the driver, he saw me clearly and slowed down. I asked if we could go with him. He said, “No, no, no, I have very serious cases” and then he drove off.

When the shooting stopped, the boys near me started running, left and right. I stayed by myself and then decided to walk away. I walked for about five to seven minutes towards my car. I was trying to call the office in Jerusalem – it took a while to get a signal back then when mobile phones were still quite new. As I was walking, I saw a colleague from another news agency.

A few people asked me how much we sold the pictures for. But France 2 said, 'We will not make money from the blood of children.'

I asked him, “How many injured, how many killed?” He told me about three. I said, “Look, if you are talking about the three dead, add another two. I think there are another two, they were killed against the wall.” I showed him what I had filmed and he started screaming, “Oh no! Oh no! This is Jamal, this is his son, Muhammad, they were in the market. Oh my God, oh my God!”

I asked him, “Do you know them?” He replied, “Yes, I am married to his sister.”

The office was silent

I called Charles and he asked me, “Where have you been?” I said, “Don’t talk to me, I am very tired.” He said, “OK, you’ve got until 5pm, go feed it right now.”

When I fed the footage, everyone in my office in Gaza and in the France 2 office in Jerusalem went quiet. You couldn’t hear any noise. Everyone was astonished; even the journalists around me.

Charles spoke first. He said, “OK, Talal, I think you need to rest because this is unbelievable. But are you sure no one else filmed it?”

I said, “I was on my own, you can write exclusive for France 2.”

He said, “OK, go rest” and I went back home.

‘The camera doesn’t lie’

Then Charles called me back and asked me some questions: the angles of my footage, my position, how, who – a lot of questions. It aired at 8pm that day but Charles had to deal with a lot of questions. High-level people in Paris and Israel, he called the Israeli army, as he was obliged to, according to the law. These were strong pictures.

High-level people in Paris started asking me questions. I answered it all, knowing that Charles trusts me and knows who I am. I am not biased. From the beginning, before I started working for France 2, Charles told me, “Talal, don’t be biased.” And up until now I have taken him at his word, not to be biased.

There was a lot of talk about this video, claims that it was fake. But the people saying this didn’t even know the area. There were a lot of calls and investigations with me about how true the images were. I had one answer for them. The camera doesn’t lie. Whatever they say about these pictures, it can’t hurt me, except in one way – my career. They hurt what I am working for – journalism. To me journalism is my religion, my language, there are no borders for journalism.

I received a lot of awards for that video. I was honoured in Dubai, in Qatar, even in London twice. I received awards from America and France. I really don’t know how these people think we could have staged it.

The day after the shooting, I went to the hospital to see Jamal. I could not talk to him too much. I took a few pictures and spoke to a doctor who told me that Jamal’s condition was very bad, that there were a lot of bullets in his body.

A few people asked me how much we sold the pictures for. But France 2 told me the images would be distributed for free and I was in agreement with them. They said, “We will not make money from the blood of children.”

The court case in Paris went on until 2013. We won. We didn’t receive any money at all from the case. It was the dignity of our job that pushed us to fight the case.

As told to Nina Montagu-Smith

This interview was first published by Al Jazeera in September 2020.