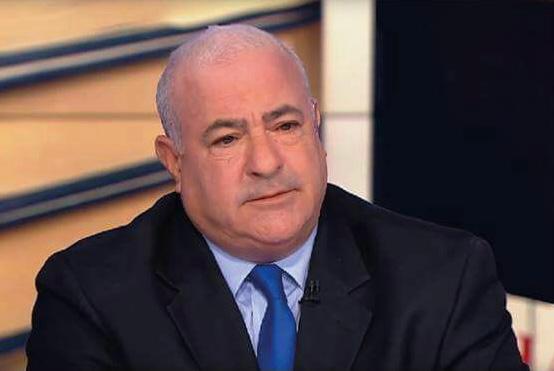

Al Jazeera’s Washington correspondent recalls the events of September 11, and explains how life for him as a Muslim journalist in America was forever changed in the aftermath.

Looking back to the morning of September 11, 2001, I remember it had been an extremely slow news season that summer.

The whole month of August and early September was the worst season ever. The US news networks were busy with Chandra Levy, who was an intern at the Federal Bureau of Prisons in DC and was the lover of a California congressman. She was missing. Every single day we used to get the daybook from CBS News, and every day in the daybook was written: “Today we have a camera at Chandra Levy’s parents.” It was the ONLY story. It was slow—in the month of August, everyone is out of town. But that particular summer it was absolutely dead.

There was no Al Jazeera English back then, and we had just a very small bureau in Washington DC. There was only one correspondent actually when I joined, so I was the second one. It was small, and, still, “Jazeera” was hard to pronounce for a lot of US officials. When you called them, they would ask: “Al Ja-what?”.

I think I made history that day. I was the first one to tell Al Jazeera about the issue. I remember walking into the lobby of the National Press Building—I always used to be the first one to get to the office—probably a bit after 8am.

There used to be three TV sets in the lobby next to the security desk, and, on one of them, I could see the beginning of the live shot on one of the morning shows of the first plane hitting the Twin Towers. The assumption was, as I gathered from a couple of people watching, that it was an accident—a horrible accident.

So, I went to the office, and I called Doha. I said: “Look guys, there was this accident, it sounds horrible. Perhaps you can carry the live feed from CBS.” And that was how Al Jazeera ended up covering the second hit, because of that call. Otherwise they would not have been interested so soon.

And the rest is history.

‘Like a Scene from a Movie’

When the second plane hit, I was shocked. I was on the phone with Doha at the time and I still did not want to believe it was a terrorist attack.

I was talking on the air [over the phone], saying: “It is hard to believe but maybe some catastrophic technical problem happened.” I said that the planes were equipped with the latest technology to alert the pilots if there was an obstacle, like a mountain or a building. And maybe it had failed. I did not want to believe it was a deliberate act.

In that initial moment, I was the only reporter in the office and I was talking to Jazeera by phone. It was hard to get the connection to go on camera because you had to go through satellite companies back then. And then I was on the air being asked about all the rumours that had started flying around—had the State Department been hit? Had the White House been hit?

We were a few blocks away from the State Department as well. But I could not leave the office in the initial moments.

Finally, when I got outside, it was like the end of the world.

I will never forget that day. People panicking. All the traffic was one way out of town. There was smoke later out of the Pentagon building when it was hit.

I had never seen—and I hope I never see again—such panic on people’s faces, it was just unbelievable. It was like a scene from an end-of-the-world movie.

And there were so many emergency cars. Every model and make of any car you can imagine. I had no idea the emergency services had so many different types of cars—small, big, vans with the emergency lights on.

September 11 changed everything radically for me and for journalism. It changed how I was perceived as 'Mohammed' and I suddenly started having to somehow prove that I was not a 'bad' Mohammed

Eventually I walked to the State Department to check out the rumours that it had been hit and then there was talk about the plane going towards Congress, but that didn’t materialise.

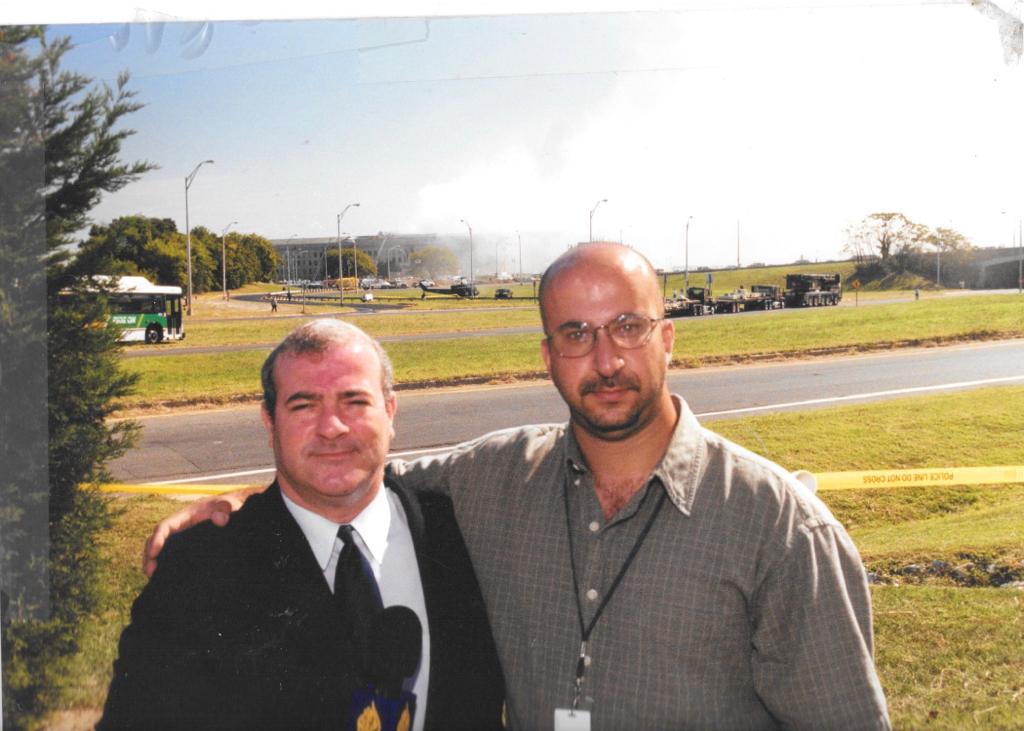

I ended up going later in the day to the Pentagon and got a few live shots from there with smoke still coming out of the area with the smell of it. I remember that smell to this day.

I got in a cab with the cameraman to go towards the Pentagon because that was the only spot—thank God—in DC that was hit. And I remember the driver of the cab we got—just by accident—was a bearded man. I don’t know where he was from—Pakistan or Afghanistan.

We were stopped by the Virginia State Police at one of these little checkpoints on the 395 highway going towards the Pentagon, because the Pentagon is actually in the state of Virginia, and he said: “Where are you going”. And we said: “Well, we are going to the Pentagon!” I could tell from their facial expressions, they were quite alarmed. But they let us through!

‘I Knew We Were Going to Go to War’

I found there was also a professional-personal conflict. I was very worried about my daughter, who was at school. She was about to turn 12. I tried to contact my wife so she could go pick her up, but the phone service was unbelievable, it was bad.

Everybody was using their phone; everybody was calling everybody. It was just collective panic in the city.

I did not have any idea how I wanted to go about covering what was happening. I just tried to take one minute at a time, trying to absorb what was going on. It was just too much.

Half of me was worrying about my own family, and what was happening. but once I realised this was a BIG story and this was terrorism, I started to realise that we were going through a very historical day and there would be a lot of ramifications for the US and the world. And I knew we were going to go to war—or the US was going to go to war, for sure.

I knew, also, professionally, it was going to be extremely busy, very unlike the season we had just had over the summer. There was not going to be another slow news day for a while.

Becoming the Story

Life changed a lot for me in the aftermath of 9/11—both personally and professionally.

In November, I was detained in Texas. Vladimir Putin was the first foreign leader to visit Bush after the events and he was going to visit him in Crawford, Texas, at Bush’s ranch. So, I went there and, of course, the office made all the reservations using the business credit card from the office, and the name on the card was “Al Jazeera”.

Al Jazeera was starting to become a familiar name [in the US] because of our coverage in Afghanistan following September 11. Before that, it was really hard to get people to talk to us; we were a small network not known in the US. And when you said: “Al Jazeera”, they would say: “Al what?”

So I flew to Houston and then from Houston, I flew on a small plane to an airport near Crawford, Texas. It was the closest airport to the ranch. I landed in this very tiny airport and I went to get my rental car. A lady from the car rental company gave me the keys and said: “OK, the car is just across the street.”

But then, while I was on the way out, two policemen came out to talk to her, and then they came up behind me and asked me to stop and wait. It was a Wednesday and I was supposed to do a live shot at 4pm for the main news bulletin at 11pm, Doha time.

I said: “Wait for what?”. They said: “We have to wait for the Secret Service”.

They explained: “We have reason to believe that the credit card you used has something to do with Afghanistan.” I said: “Excuse me? As far as I know, Mullah Omar does not issue American Express!”

What had happened was the rent-a-car lady had seen a “Mohammed” with a credit card that said, “Al Jazeera," which had put her in mind of Afghanistan. So, she mentioned that to the police, and to be on the safe side, they decided to detain me.

It was 40 miles between the airport and the ranch. So, I called the office and told the bureau chief: “I cannot make it to the live shot in Crawford.”

And, so, I became the story.

Al Jazeera put out: “Breaking News, our correspondent has been detained," and at that moment, there was an army of correspondents at the ranch as it was a big story—the first foreign leader to come to the US. Then they heard there was this certain Mohammed detained at the airport who was on his way to the ranch!

I was one of the few journalists to visit Guantanamo Bay. I said: 'This island is full of Mohammeds, but I am the only Mohammed who can get in and out.'

After a couple of hours, the Secret Service showed up, and I had an interesting conversation with them. Thank God, my wife had insisted that morning that I take my US passport with me, even though it was a domestic flight. She said, “You never know," and she was absolutely right.

So, I gave them the US passport, and I thought that would be the end of it. But they started looking through the foreign trips and visas. I had travelled in 1994 to Tunisia to cover something when I was working with Voice of America, the radio station that was part of the US State Department. They asked me, “What were you doing in Tunisia back in ‘94?” This was seven years later, and I was getting mad by then. I said, “I am a US citizen, you already checked my passport and my credentials. It was your government that sent me to Tunisia!”

In the end, they escorted me to the ranch, and I found out I was the star of that trip because everyone wanted to interview me! I was more popular than Vladimir Putin for a couple of hours! Finally, Mohammed had made it to the ranch!

Later on, my daughter was invited to the White House as part of an outreach programme by the White House to show the American Muslim community that it was not Islamophobic. In fact, the Bush administration went out of its way to prove it was not anti-Muslim. So, my daughter went to the White House, and Bush came in and started talking to my daughter—she was a little cute girl with a Moroccan kaftan on—and he said: “How are you?” And she said to him, “You arrested my dad!” And he apologised! I still have a picture of her with him.

Not a ‘Bad’ Mohammed

That day, September 11, changed everything radically for me and for journalism. It changed how I was perceived as "Mohammed,” and I suddenly started having to somehow prove that I was not a “bad” Mohammed, even though I was a US citizen—I'd been a citizen for a long time, covering the US for a long time by then.

One of the big issues was Guantanamo Bay and I was one of the few journalists to visit it. On one of my trips in 2004, I went to interview the general who was running the whole place. We would have to cross the bay—the water body between where we stayed and the prison camps—and I was talking to a bunch of my colleagues from different US media outlets, and I said: “This island is full of Mohammeds, but I am the only Mohammed who can get in and out.”

I remember the New York Times guy saying: “Oh Mohammed, if you don’t mind, can I put that in my story?” I said: “Sure!”. So that’s how I felt personally, just carrying the name Mohammed, covering the aftermath of September 11.

Another time, I was at Dallas airport travelling to do a story related to 9/11 and travelling by plane had become very difficult: “Take off your socks, take off your shoes, no water, no this, no that.” America had lost its innocence.

So, the cameraman and I were in this long line and some airport staff were trying to push a woman in a wheelchair through the line behind me. Because of the noise, I couldn’t hear them speaking to me—they were asking me to move to make way for the lady in the wheelchair. Finally, the cameraman said: “Mohammed!”, and I swear to God, the entire line of people stopped. Like, you know, “Mohammed” was not supposed to fly!

Even in a democracy, as a journalist, you can be lobbied to become a government mouthpiece.

Professionally, it was a completely new story to cover in so many respects. The US Government was doing things it had not done since the Civil War—detaining people with little regard to the law or to US traditions. There was also a surge in the extreme right-wing media.

And, from my own observation, that was the beginning of this deep division in society in the United States. Maybe not during the initial time or the start of the war in Afghanistan, but by the time the war in Iraq started in 2003, it was a completely different country and I think that is going to stay with us for a while.

It was the sort of division that had not been seen in US society since the civil war, where people just cannot see the other side. They cannot agree on anything—on the vaccines or COVID-19. Even the wars. The Democrats supported Afghanistan but were vehemently opposed to the Iraq war. The Republicans were all the way for the Iraq war, but they didn’t care all that much about Afghanistan until now, for political reasons.

The US has changed profoundly, and I think that division coming from that one day—September 11—not only affected the world at large and brought about two wars, but also all this waste of human lives and money.

Learning to be Sceptical

What I learned most from covering September 11 was to be much more sceptical of government statements and declarations.

In the early days of the war in Afghanistan, the US bombed a wedding. More than 40 people died. They thought it was an al-Qaeda gathering, but it was just a group of regular, innocent people at a wedding.

Of course, Al Jazeera covered this, and I remember in those early days we had become a bit of an enemy of the US Government. They attacked us on a daily basis, and as a correspondent in Washington, it really complicated my professional life. We were the “al-Qaeda network”, a “terrorist” network.

The public perception of Al Jazeera in the US probably did not change until the war on Iraq started losing popularity. Then the American public opinion started looking differently at Al Jazeera.

Donald Rumsfeld, the US Defence Secretary at the time, attacked us during one of the Sunday talk shows after we had covered this story about the wedding. He attacked Al Jazeera on the set, suggesting we were siding with terrorists. So, I asked him: “Mr Rumsfeld, are you accusing us of faking the footage? Do you think we made it up?” He just looked a bit startled at the question and moved on to someone else.

At least I was operating still in a democracy. In a few countries they could be at war and the correspondent faces the defence secretary and there might be a margin [of how safe it is to do that]. At least, being in the US, you can face a government official and still go home!

But it taught me to be extremely sceptical. If the government is at war, it needs media support. Even in a democracy, as a journalist, you can be lobbied to become a government mouthpiece.

Staying Neutral

It is hard to remain neutral, especially if you become part of the story and you have reason to be worried about your own safety—and that of your family—even in the country you live in.

However, in addition to maintaining scepticism, I think the first thing to do is to try to be neutral, even vis-a-vis things that could normally be perceived as “true”.

Because the first victim of wars is the truth.

Sometimes you get caught up in rumours—and, nowadays, it has got a lot worse with social media. You have to be sceptical not only of the decision makers but also of the public. You don’t know who is going to try to affect your position and your view. Just working out if what you see is the truth or not can be kind of maddening.

You really have to be extremely careful what you are reporting and how you are reporting it.

As told to Nina Montagu-Smith

Main image: Mohammed Alami and his team prepare to go live in front of the smoking Pentagon building in Washington, DC, on September 11, 2001. [Photo courtesy of Mohammed Alami]