For one journalist in Nigeria, covering the activities of the militant Islamist group, Boko Haram, primarily means documenting the horrifying stories of its victims, sometimes to his own cost

I was 19 when militants from the oil-rich Niger Delta region in southern Nigeria began trying to acquire control of the region’s petroleum sources in violent clashes and armed attacks on oil wells and pipelines in 2004. The government retaliated with a massive military crackdown which was to last for five more years, when the militants accepted the government’s offer of amnesty, bringing the conflict to an end. It threw many parts of the region into chaos.

Throughout the period of conflict, I was studying Marine Biology at the University of Calabar at the edge of the Niger Delta region and, because the militants operated from bases along the coast, it was often impossible for oceanography students like me to go on field trips in the coastal areas.

It was the first time I had become properly aware of how conflict can play out for people in my country and at the time, I kept wishing I was a journalist so I could write about how it was affecting the lives of those in the communities around me.

In August 2009, the month I turned 24, we were celebrating what seemed like the end of the Niger Delta conflict when the news came that the Islamist group, Boko Haram, was expanding its uprising against the Nigerian state, attacking government institutions and staging a campaign against “Western” education. The activities of the group would cause the deaths of thousands and the hardship, suffering and displacement to hundreds of thousands over the following years - many of them women and children.

"What is happening in Nigeria again?" I remember asking a close friend of mine, who was born in the northeastern city of Maiduguri, where Boko Haram was founded, but was living and working in Calabar. "You should find out for yourself," he said to me.

The violence escalates

I began researching the history of the group and learned that when the Muslim cleric, Mohammed Yusuf, founded Boko Haram in 2002, his ultimate aim was to establish an Islamic state in Nigeria which had sharia criminal courts and eliminated any form of “Western” education across the country.

Nigeria’s more-than 200 million people are nearly evenly divided between Christians, who dominate the south of the country, and the primarily northern-based Muslims.

Islamic law was implemented in 12 northern states after Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1999 following years of military rule.

Boko Haram, which means “Western education is prohibited” in the local Hausa dialect, called for the enforcement of sharia law even among non-Muslims, however.

At the beginning, Yusuf’s sect had no intention of using force to achieve its aims. But all that changed when a clash with security forces in Maiduguri July 2009 - after Boko Haram members refused to adhere to a new law that required motorbike users to wear helmets - led to the death of nearly 1,000 people and motivated the group to radicalise.

It all began when a member of Boko Haram died, and as other members were on their way to the cemetery to bury him, they were stopped by policemen who asked them to explain why they were not wearing helmets.

The police fired shots during the ensuing argument, injuring several members of the sect. In the hours that followed, Boko Haram responded violently by attacking government buildings and police stations, first in Maiduguri and, later, in other parts of northern Nigeria, before security forces curtailed the violence and arrested Yusuf.

Yusuf was reportedly executed while in police custody, leading to the emergence of his deputy, Abubakar Shekau, as the new leader and the continuation of Boko Haram's violence.

Telling the stories of the victims

As many fled the violence in the northeast to other parts of the country, including to Calabar, I had the opportunity to find out firsthand what life was like in a region blighted by a violent jihadist movement. I listened to stories of young men held and killed by militants, told by family members who were forced to watch as their relatives were slaughtered; ordeals of torture by militants; and narrations of houses razed, sometimes with children inside.

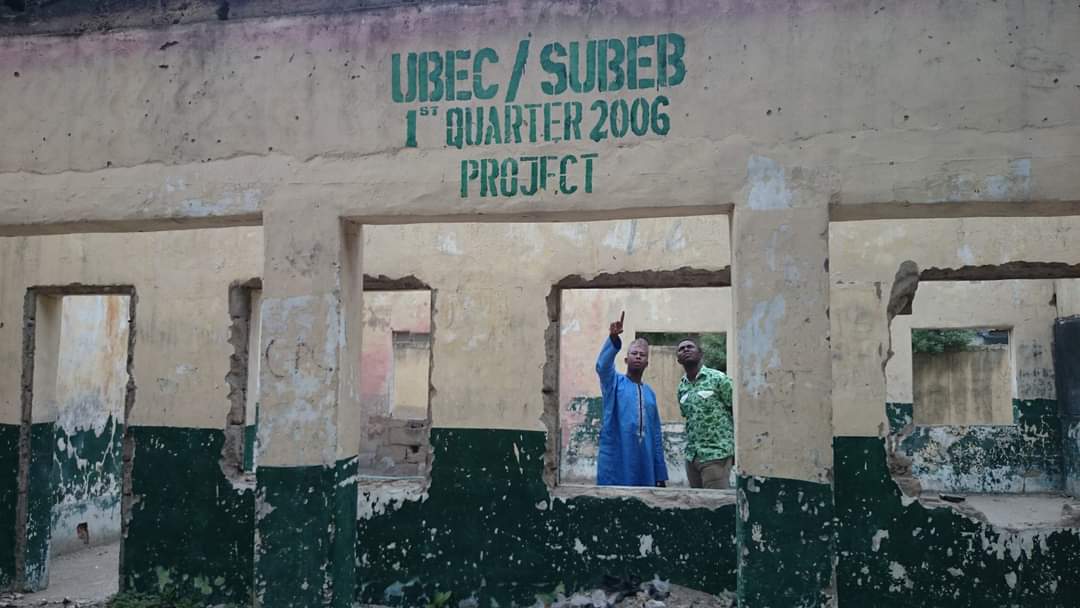

I wrote down those experiences - along with articles aimed at pressuring the government to create programmes that would help children in the northeast achieve basic education - and shared them on Facebook. Some went viral, helped by the fact that some local newspapers and other publications picked them up.

The fact that my posts were gaining so much engagement and interest, and were prompting conversations everywhere about the need to protect children in conflict zones, convinced me to pursue my lifelong dream of becoming a journalist.

Despite not having any news medium other than social media to publish my stories, I was keen to travel to the northeast to see the humanitarian situation in the area for myself and document the accounts of victims of Boko Haram violence.

But it was 2013 and the northeast region had become a very dangerous place for anyone looking to report on the atrocities of Boko Haram.

The previous year, the group had carried out bomb attacks on the offices of This Day in Nigeria's capital, Abuja, and a building where the offices of ThisDay, The Sun and The Moment in the northwestern state of Kaduna are housed. It followed this by releasing a video in which it accused the media of misrepresenting its activities.

At this time, Boko Haram had already murdered two journalists - Zakariya Isa, a reporter and cameraman for the state-run Nigeria Television Authority who was shot in front of his house in Maiduguri in October 2011, and Enenche Akogwu, a reporter for the independent Channels Television, who was shot dead the following January when covering bomb blasts in the northwestern state of Kano.

Men came looking for me, armed with Kalashnikovs

Despite the risks associated with reporting on the activities of Boko Haram, in September 2013, I made the trip to Maiduguri along with Kunduli Agafi, my friend from Calabar who was returning to his home city. Just like me, he had become interested in journalism and also wanted to document the accounts of victims of the conflict in the northeast region. But we were soon going to discover how hard it was to find out anything about the group.

As I entered the living room in Agafi's small flat, two strange men, armed with Kalashnikovs, arrived at the compound and began to ask neighbours for the whereabouts of “the boy who always wrote about [Boko Haram] on Facebook”. I could hear them from the living room.

So, while the conversation continued, I sneaked out of the compound through the back and rushed to a bus station where I boarded a bus to Damaturu in neighbouring Yobe state, and eventually found my way back to Calabar from there.

That wasn't the end of it, though.

Weeks later, Agafi found out that a complex of 12 shops owned by his family had been burned down by Boko Haram militants in Maiduguri as retribution against him for playing a part in efforts to expose the atrocities of the sect and for joining in the campaign to ensure that children achieved basic education.

I initially resolved never to return to the northeast following the September 2013 incident until Boko Haram was defeated. But the group's atrocities continued - such as the 2014 kidnapping of schoolgirls in Chibok which garnered international attention. Meanwhile, children continued to be exploited by traffickers and slave masters. I had now become a reputable freelance journalist whose articles have been published by platforms like Al Jazeera and The Daily Beast, so I couldn't help but go back. I needed to listen to kids tell their own stories of how they managed to survive the catastrophe in the area, and try to give them a voice.

And that is what I have been doing ever since.

In order to stay safe, I usually have to spend nights in hotels where Nigerian soldiers are securing the facility, and they don't come cheap. And because the budgets for freelance journalists in many organisations have drastically reduced as a result of the impact of COVID-19 on media outfits, I've always had to dip into my own pocket to cover part of the cost of accommodation and other logistics, which also includes paying local security groups, such as the Civilian Joint Task Force in Maiduguri, to provide security while moving around villages in a bid to carry out interviews and access the impact of Boko Haram's militant campaign on local communities.

Monitored by militants

When it comes to being monitored by militants, I am not alone. In 2015, Boko Haram threatened to kill ThisDay features editor Adeola Akinremi in retaliation for an article he wrote urging the government not to grant amnesty to members of the sect, as it will amount to "injustice to the children orphaned by Boko Haram and the women who have become widows,” Akinremi had stated.

Journalists like Timothy Olanrewaju and Njadvara Musa who've been covering the activities of Boko Haram from Maiduguri since they began have reported being traumatised as a result of what they've experienced since the conflict started. Like so many journalists who've covered the violence, they've seen corpses littered around them and come close to being killed themselves.

Even listening to victims of Boko Haram tell their heartbreaking stories can sometimes be traumatising. I personally felt that way about eight years ago when I made one of my earliest trips to Maiduguri to report about the group.

Traumatised by trauma

In mid-2014, I sought to gain insight into the true nature of Boko Haram. A local resident guided me to Markaz Ibn Taymiyyah, as the group's first ever camp - named after the 13th Century Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyya - was known, in the heart of Maiduguri.

The camp had been destroyed by the Nigerian military shortly after the group's first uprising in 2009, but it was disheartening to remember that it was once a place where Boko Haram members envisaged an Islamic State at least in northern Nigeria and where some must have thought of slaughtering any opposition to the idea.

I became severely distressed when I listened to a 12-year-old orphan recall how his parents were killed by militants and heard a 16-year-old girl vow she was never going to walk on the streets of Maiduguri alone again because she feared she might be raped a second time.

For months I found it a huge struggle to speak to children affected by the violence because I couldn’t bear to hear their heartbreaking stories. It took a couple of counselling sessions with a faith-based psychologist for me to regain the courage to speak to kids in the region.

While it is a privilege to be able to tell the stories of the people affected by this sort of violence and disruption, it is also important that journalists constantly weigh the benefits of the stories they pursue against the risks involved and know when to back down. No story is worth getting killed for.

Journalists going to places in the northeast of Nigeria where there is likely to be crossfire, should consider wearing body armour and combat helmets to provide protection from flying shrapnel. I would also recommend that journalists seeking to report on events in this region take a training course for covering stories in a combat zone.

Finally, it is very important that journalists who perhaps have been subjected to physical or psychological abuse such as torture or even witnessing how others were tortured seek professional counselling to help deal with the trauma that they may be experiencing.