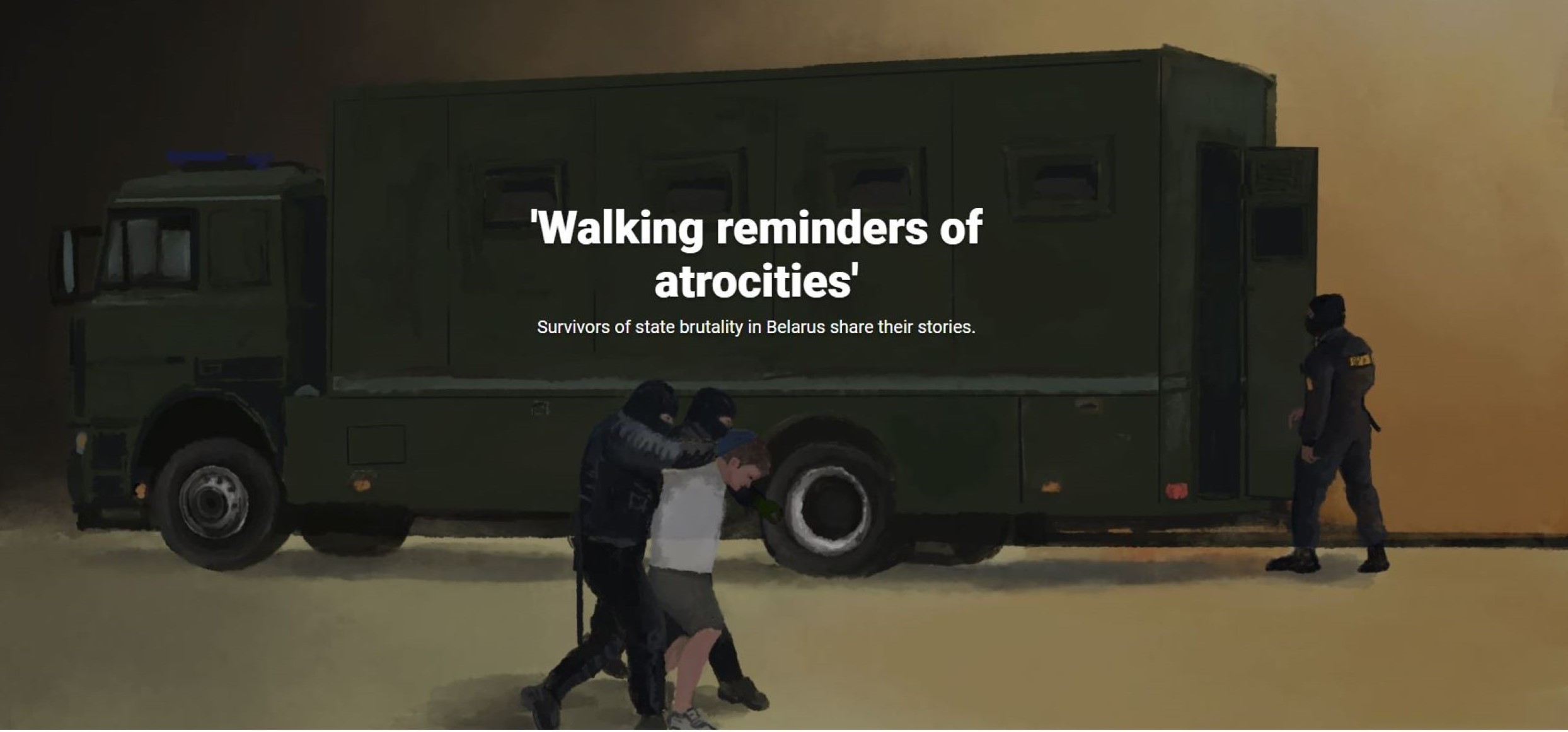

Constructing a long-form feature to document the narratives of Belarusians imprisoned for protesting after the 2020 presidential election was a pain-staking, months-long task fraught with danger

For almost three decades of Lukashenko’s rule, Belarusians have been learning to live between two realities, one portrayed by the state-owned media, and the one that they experience every day.

People outside of the country shuddered watching or reading about the unprecedented brutality that Lukashenko's regime unleashed on peaceful citizens after the presidential election of August 9, 2020, in Belarus.

But, apart from the news reported by a handful of independent outlets whose objective coverage of protests and police crackdowns was swiftly squashed, it was business as usual for the rest of the media in Belarus. On state channels, protesters were labelled “hooligans and prostitutes” and accused of disrupting public peace and attacking the police.

As the first few days following the election turned into weeks, the attention of the international press shifted to other global crises. In the meantime, to those who were still following the human rights crisis in Belarus, it was becoming apparent that what was happening in Belarus was extraordinary, and it was going to continue.

Between August 9 and 12, more than 6,700 Belarusians were arbitrarily detained (many of whom never went to the protests), more than 4,600 were tortured in jails, precincts, vehicles and on the streets, and four people were killed by the police. Not a single policeman has been indicted. Instead, 300 of them received presidential awards for their “excellent service”.

I, Olga Loginova, am a Brooklyn-based Belarusian-American documentary filmmaker and journalist. I watched as my former colleagues, friends and fellow Belarusians were being brutalised on the streets of my home city of Minsk. I decided I wanted to tell a story that would go beyond the scope of the short-lived breaking news. I also knew that being as emotionally involved as I am, I needed a partner to give the story the objectivity, depth and justice it deserved.

So, I teamed up with Ottavia Spaggiari, an Italian journalist whose work focuses on human rights and social justice issues. Together, we decided to work on a long-form print piece that would painstakingly reconstruct the post-election events, explain the shortcomings of international human rights law and give narrative justice to the many survivors of the regime’s atrocities.

One of the goals that we wanted to achieve with this story was to explain why what happened in Belarus was relevant to the rest of the world. The impunity of the Belarusian regime has exposed, once again, the shortcomings of international human rights law when it comes to holding authoritarian regimes accountable for the crimes. To understand the legal mechanisms at play, we interviewed dozens of lawyers, academics and legal experts.

When we started reporting, we did not expect that in less than two years, Belarus would be pulled into a war. The 2020 crackdown on civilians resulted in the isolation of Lukashenko's regime from the West, pushing it even closer to Russia and recently allowing the Kremlin to use the country as a springboard for its war in Ukraine.

There were several challenges that arose when we were reporting this story. Always hostile to independent press, the Belarusian regime had fully cracked down on journalists after the election in 2020. International press outlets lost their accreditation and Belarusian journalists were persecuted. For our own safety that of our sources who were still in the country, we decided not to go to Belarus, and instead to report from the US and Europe.

Early on, we decided that this story should be told through personal accounts of the August 2020 participants. Through Telegram channels - a popular method of secure communication in Belarus - I was able to connect with groups of men and women who had been incarcerated together in the notorious Okrestina jail in Minsk. Talking to multiple people over a course of many months allowed us to corroborate individual accounts and recreate nuanced, extremely detailed - if nightmarish - scenes from inside the jail.

When we started reporting, we did not expect that in less than two years, Belarus would be pulled into a war

The second challenge was that we took on this long-term project as freelancers. Even with the flexibility that online communications allowed, and the fact that I grew up in Minsk and knew it intimately, it was clear that this story could not be told from the comfort of our couches. Many key sources in the story had fled to the European Union, so we decided to meet them there. Like many long-form freelancers we needed additional funding, which we finally secured through the International Women’s Media Fund and Journalismfund.eu.

In July 2021, I flew to Poland and, then, Lithuania to interview sources on the ground. The Belarusian regime is notorious for its violence against journalists and activists. The physical and digital safety of our reporting team and our sources was a top priority. We had several consultations and training sessions with security experts which enabled us to safeguard our work in the field and online.

Even though Poland and Lithuania are part of the EU, the sense of threat was palpable. Our sources spoke of undercover KGB squads operating in Poland. One of my sources was under 24-hour police protection, another carried an axe in the trunk of his car. While I reported in Europe, Ottavia monitored my movements.We had daily check-ins and debriefs with each other, both reporting-related and psychological.

All documents, drafts, photographs and notes were stored in an end-to-end encrypted Cloud-based storage system. All interviews were conducted over end-to-end encrypted channels. Names of sources who were injured or jailed after the election were first encoded and then changed for their safety.

When the field reporting was over, it was time to organise our data and start writing. To better grasp the numerous individual storylines and to understand how each story could contribute to the overall narrative, we built detailed timelines for our key sources.

By mapping their whereabouts and experiences between August 9 and August 12 (the day some of them were released from Okrestina detention centre) we were able to create a vivid narrative of the unprecedented post-election crackdown in Minsk, and to understand the underlying patterns and tactics used by the regime to suppress the pro-democracy movement.

A painful but important part of the process was deciding which stories would make it into the narrative, and which would have to remain in the background. It was a difficult task, because every story shared with us was important. In the end, we decided to select stories based on chronology and uniqueness of experiences. We made sure that every event we described helped us move the overall story forward.

We continued reporting on the piece long after the draft was submitted for review. Our final interview with one of our main sources, “Max”, happened just several days before the story was published. At that point, Max had already left Belarus, fearing he would be drafted and sent to Ukraine. As he boarded a train from Moscow to Vladikavkaz hoping to cross over to Georgia, our story was published. He read it on the train out of there.

The article by Olga Loginova and Ottavia Spaggiari documenting the stories of political prisoners in Belarus was published by Al Jazeera on March 17, 2022