Philip Obaji Jr has devoted years to uncovering and reporting on the sexual abuse and human trafficking of displaced women and girls in Nigeria. This is his story

Five years ago, I started writing about the trafficking of displaced women and children in West and Central Africa - those who had been forced to flee their communities as a result of conflict. My vocation came about almost by accident.

I had travelled to the northeastern Nigerian city of Maiduguri, where Boko Haram was born, to speak with victims of the armed jihandist group who were living in Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps. I wanted to talk to them about the challenges they were facing while trying to survive in what was now their new home.

But through all my conversations with the women and girls in the two large camps I visited, there was one common thread which emerged - tales of sexual abuse and the horrors of human trafficking. The majority of the women I interviewed had either been sexually abused or had come into contact with human traffickers, frequently posing as agents offering them work as maids in far-away cities.

I spent the whole of 2017 pursuing a series of articles that eventually became some of the most revealing stories published anywhere about human trafficking. My year-long investigation for The Daily Beast uncovered the horrendous fates of children once enslaved by Boko Haram who were then approached by people-smugglers and sex traffickers, and taken on dangerous journeys to Europe, with girls being forced to visit traditional ritual shrines for oath-taking rituals binding them to their “benefactors”.

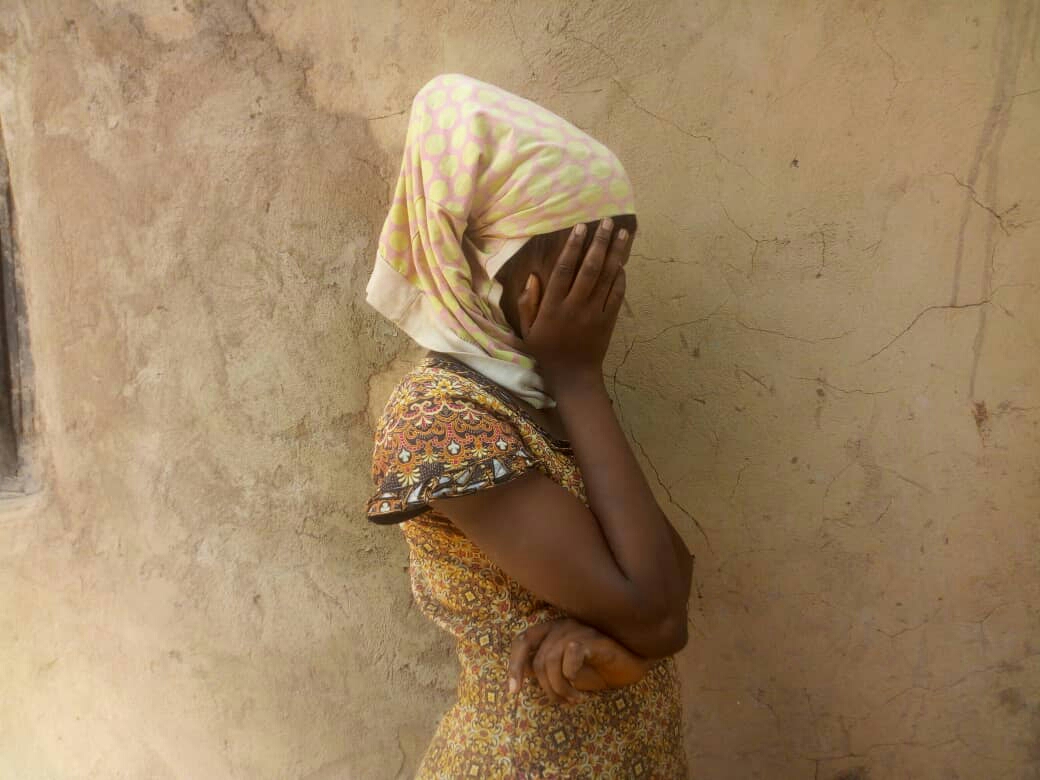

I interviewed 17-year-old Sarah - the false name we used for my piece - who had been approached in an IDP camp by an agent for a trafficking ring operating from the southern City of Benin. She told me about her meeting with the trafficking agent and I re-told her story in my article, How Boko Haram’s Sex Slaves Wind Up as Sex Workers in Europe. The piece led to the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) in Nigeria increasing its surveillance in IDP camps, with the head of the agency’s office in the northeast confirming to The Daily Beast that it was taking steps to “sensitise IDPs about trafficking and give them our numbers so that they can report any person who comes to the camp for the purpose of trafficking people either to Europe or other parts of the country”.

In my next article, Blood on Their Breasts, a Curse on Their Heads: The Juju Ritual Torturing Italy’s Sex Workers, I found out how another 17-year-old, who had fled the war in Maiduguri to Benin City, was forced by her trafficker to undergo an oath swearing ritual in which a part of her areola was cut off by a juju priest, and her blood and pubic hair used for the ritual. It prompted me to investigate further this ritual which had left the young woman with keloids around her nipple and a burning sensation that has never entirely gone away.

So, I went to a shrine in Benin City and watched as a woman held her left breast in pain, after swearing an oath that she would remain loyal to her “husband and benefactor” while she was in Italy. I had seen, and then revealed, a horrific ritual that previously had not been reported.

Treading the path of slave traders

My third article, When the Way Out of Boko Haram Is an Ancient Slave Route, focusing on people-smuggling and trafficking of children from the northeast, was a particularly dangerous one to report.

In February 2017, I met four boys - one of them a former Boko Haram captive whom I had interviewed in the past - at a bus station in Maiduguri waiting to board a bus to Kano, from where they would go on to Niger. They were with an agent for a smuggling ring whose job was to hand them over to a people-smuggler once they arrived in Kano. The people-smuggler would then be responsible for taking them across the border into Niger.

I decided on the spur of the moment to join them in the journey to Kano so as to get a picture of how easily smugglers get away with their businesses.

I had discovered that smugglers were transporting children who were trying to escape the conflict in northeastern Nigeria to Niger using the same route that foreign merchants, who bought black slaves from Kano centuries ago, used to transport them. The merchants would take slaves through remote desert villages in northern Niger to Fezzan (as the southwestern region of modern Libya was known) from where they sold them to Arab traders and owners.

These days, smugglers travel out of Nigeria with their clients with ease because the police focus mostly on private cars while they allow commercial vehicles, which smugglers use to transport their clients, to pass after the drivers pay small bribes to the officers.

As I wrote in my piece about what happened, “despite the risk involved, the four boys hoping to reach Italy were undeterred. For them, it seemed, the risk couldn’t be worse than a life of uncertainty in an area where no one knows when the next Boko Haram bomb will go off.”

After the boys were handed over to the people smuggler in Kano, I waited for five hours for news that they had safely crossed into Niger before returning to Maiduguri where I planned to interview children in IDP camps about trafficking.

There, I found Sarah who was also preparing to leave for Benin City to meet a trafficker she referred to as “Madame Eunice”. Sarah shared the address she had been given with me, before she went. A week after Sarah had departed, I visited Benin City - 1,429km southwest of Maiduguri - and went straight to the address Sarah gave. It wasn’t a residential home, as we both had thought, rather, it was a temple, where she presumably had been expected to swear an oath of allegiance to her trafficker.

I sought out the priest in charge of the temple and told him I was a close friend of Sarah and was concerned about her whereabouts. I showed him a photo of the girl and he quickly recognised her. She hadn’t spent the night at the temple, he said. On the same day that Sarah arrived, the teenager took part in the ritual along with the other girls Madam Eunice planned to traffic to Italy.

The priest slaughtered a chicken and the girls swore over its blood that they’d keep to the promise they made to their madam. Should they fail in any way, the punishment could be “death or an illness no one can cure," the priest told me.

The girls were asked to cut their fingernails and a part of their hair, and leave them in the shrine before departing. It is only when they’ve paid their madam back in full or when both parties decide to terminate the agreement that the priest returns the items to the owners or destroys them.

“If they keep to the agreement, they won’t need to worry about anything,” said the priest, who added that the girls had moved on with their madam to Kano a day after the ritual.

Again, I returned to IDP camps in the northeast, where I interviewed more than 60 children, some of whom spoke about how they had been approached by people purporting to offer them jobs in Europe. I travelled as far as Bama, through areas where Boko Haram fighters are still very active, to find out how girls were being abused in IDP camps and trafficked. I had to shave my hair and grow my beard, so that I would blend in and, hopefully, no one would suspect I was a stranger.

Since then, I've reported on how girls who survived Boko Haram ended up in Mexico where they were exploited by American sex tourists and Mexico's sex traffickers and revealed how a human trafficker used Facebook to advertise Cameroonian child refugees in Nigeria as maids, eventually selling one of them.

In 2019, I travelled through areas in western Niger controlled by militants in a bid to uncover how female survivors of the conflict in eastern Mali were being sold by militants to traffickers in Niger. On one occasion, I hid in the trunk of the vehicle I chartered for fear of being identified as a foreigner after my driver sighted armed militants on the main road leading to the village.

‘Up Against Trafficking’

But it wasn't until my articles on exploitation and abuse of uprooted people were published by Al Jazeera that I became well known, especially in Nigeria, for unearthing and so vividly portraying the individual stories of exploited IDPs and refugees.

In the article, ‘No girl is safe’: The mothers ironing their daughters’ breasts, published in February 2020, I revealed how Cameroonian girls in refugee camps in Nigeria were forced by their families to undergo the practice of breast ironing - a procedure intended to either stop young girls developing breasts or to flatten them once they have.

The practice is aimed at making their adolescent daughters less desirable to men in host communities whom they claim had been sexually harrasing and exploiting young girls around them.

Located in my home state of Cross River in southeastern Nigeria, Ogoja is a town I know well. I was born at the Monaiya Catholic Hospital very close to where Cameroonian refugees have settled in the Adagom community and was raised there as a child.

Nearly every year, I travel to Ogoja to visit family members and old colleagues at a nursery school who have fully settled there.

On one of my visits, a friend of mine, who's also a social worker and has been educating women about the dangers of undergoing the breast ironing procedure, told me about the painful practice among female refugees in the community and took me to visit the victims, who were all happy to speak to me.

The article I wrote about the practice became one of the most-read stories on Al Jazeera that year, and has since racked up nearly half a million views.

Three months later, I wrote another report for Al Jazeera: Survivors of Nigeria’s ‘baby factories’ share their stories, which revealed how girls who fled Boko Haram attacks were being enslaved and raped by human traffickers who then sold their babies.

In 2018, I had started a campaign known as “Up Against Trafficking” to educate women and girls in IDP camps in Maiduguri about the dangers of human trafficking after discovering that large numbers of displaced girls in camps were being approached by human traffickers in the course of my interaction with IDPs.

I arranged for a dozen social workers to act as educators and tens of volunteers to go round local communities to identify victims of human trafficking so as to refer them to concerned organisations for rehabilitation and assistance.

A couple of volunteers came in contact with the two girls I profiled in my story and immediately informed me about them. I quickly travelled from Nigeria's capital, Abuja, where I live, to Maiduguri to meet with them and I had no problems in convincing them to tell their stories as a way of warning girls like them to be wary of people promising them “paradise” in faraway places.

The article was shared hundreds of thousands of times on social media and it was a topic of discussion in many forums, including radio and TV talk shows. I was even approached by the then-director-general of the National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) asking for my assistance in reaching out to the victims in the story.

The dangers of exposing people traffickers

But while my coverage over the years of how uprooted people in West and Central Africa are exploited by human traffickers and abused by their supposed caregivers have aided concerned government agencies and humanitarian actors in better understanding the risks IDPs and refugees face especially in the camps they live, it has also shown me that reporting on human trafficking can be extremely dangerous.

As a result of exposing trafficking rings that exploit victims of conflict, last year I received a death threat via email from a human trafficker who vowed he would "deal with" me and that I would be "silenced" for revealing how he advertised and marketed child refugees as maids on Facebook. I reported the threat to the police and they promised to look into the matter. I have not heard from them since.

I've had numerous phone calls from people threatening to punish me for exposing human traffickers, and many abusive messages online via Twitter. I was particularly targeted after Al Jazeera published my story on baby factories by people looking to defend human traffickers from their home region.

Nigeria is divided into a predominantly Muslim north and a mostly Christian south. The victims in the story are northerners and the traffickers are based in the southeast, which is home of the Igbo ethnic group. Some people in the south claimed I was being used by northerners to tarnish the image of the Igbos.

The threats and abuse directed at me took a toll. I became scared and withdrawn from public life afterwards. Assurances from the police that those threatening me would be investigated did little to alleviate the fear that had consumed me. My family and close friends were worried about my safety and warned me against writing more stories about human trafficking.

For a time, whenever I received tips from people on social media about girls being exploited by human traffickers in areas close to them, I was too afraid to investigate as I didn't want to put my life at risk.

But all that changed last year when I met a 17-year-old victim of sex trafficking in Cameroon who wept uncontrollably when she recalled how a man who took her from Nigeria and promised her a job as a maid ended up handing her to different men who sexually abused her.

I came into contact with her, an orphan, after meeting her aunt at a refugee settlement in Ogoja in mid-2020 when I went round asking refugees if they had come into contact with human traffickers. Her aunt gave me her contact details and I travelled to Eyumojock in southwestern Cameroon to speak with her.

The young girl, who was taken from a refugee camp in Nigeria's southeastern Cross River State pleaded with me to tell her story and warned me that I would be "enabling more girls to be trafficked" if I didn't reveal what had happened to her and draw attention to the growing cross-border sex trafficking in Cameroon.

I couldn't ignore her plea, and so I began to research how best to protect myself from any possible attacks, having made up my mind to tell her story. I have recently finished my reporting on this story, which is due to be published soon.

Not even death threats will stop me

One of the things I have learned from my work is that, as an investigative journalist who is always going to step on toes, I have to ensure my safety - particularly online. It's the same advice I'll give to journalists in the same situation as I am - do exactly what I did. Turn on your filters, block and mute, report all threats to the police and to social media platforms, as you never know what might turn out to be serious. Once I began do that, I felt safer talking about human trafficking on social media and was emboldened to pursue more investigations on the subject.

I also found that, for investigative journalists, it is important to fully understand any risk you are undertaking when pursuing a project that is outside your regular environment. You need to research and understand who your likely adversary is and what capabilities he or she has. Finding someone who understands the environment, or knows someone who does, to give you advice about staying safe. It is exactly what I did when I travelled to Cameroon last year to investigate the trafficking of the 17-year-old refugee.

But as much as it is important to expose the atrocities committed against vulnerable people by criminal gangs and unscrupulous individuals, it is also necessary to take care over the safety of the people whose stories we tell. Protecting your sources - the victims - is an essential part of ethical journalism.

It ensures those who've been exploited by criminal gangs or even government officials in IDP camps and refugee settlements can feel confident that if they open up they will not be further victimised. Always respect the wishes and interests of victims, so as not to worsen their situation. This means journalists should be prepared to take "no" for an answer and also to avoid revealing too many personal details about those whose lives could be in huge danger for granting a press interview.

For the victims who've suffered sexual violence, it is important to apply commonsense by not revealing their actual names.

Over the years, I've learned that telling human stories is the best way to educate and motivate those who read them. But I've also understood that it is in the best interests of the people I write about if I appreciate what they've been through and do the best I can to protect them.

Going forward, I'll continue to look out for those camps, settlements, communities and migration routes where the most vulnerable have got stories to tell. Nothing, not even death threats, will stop me.