Internet blockades have been used around the world by governments keen to stifle dissent, unrest and even the reporting of war. We take an in-depth look at this phenomenon and highlight ways journalists can carry on working regardless

In July 2019, India’s Ministry of Home Affairs deployed 100 additional companies of paramilitary personnel into the Kashmir Valley and ordered the evacuation of tourists, Amarnath pilgrims and non-locals from the area. Non-local students from NIT (National Institute of Technology) - an engineering college - were ferried out of Kashmir. Government officials cited "terror threats" as the reason.

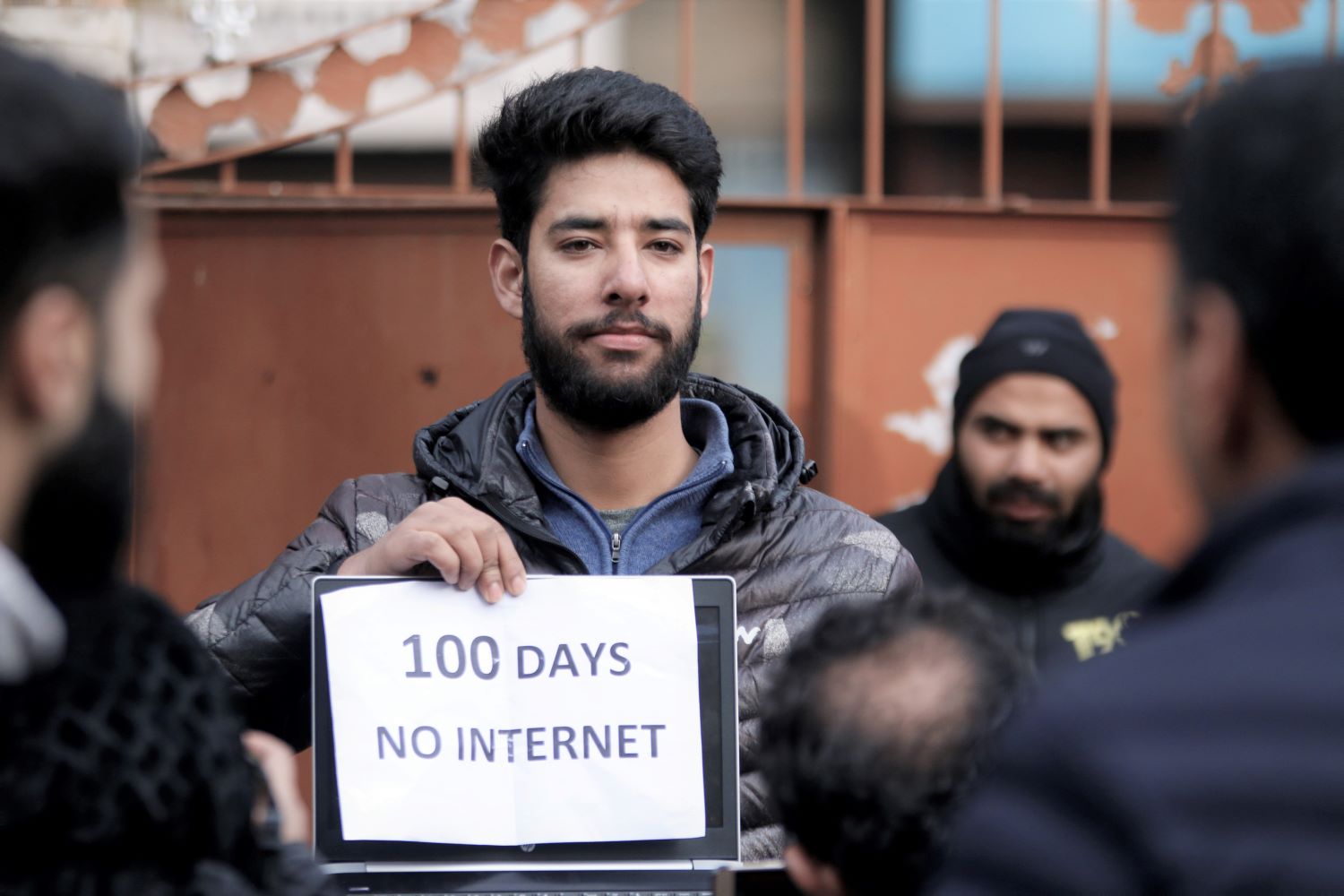

Within a few days, all communications had been blocked. It was the start of what would become the longest information blockade in the history of a democracy. From August 4, internet communications were shut down, mobile services disrupted and congregations of more than a few people banned.

Aakash Hassan - now a freelance reporter - was working as a multimedia journalist for Network 18, which is headquartered in Mumbai, at the time. He immediately set to work on a feature about the mood on the ground but quickly discovered the logistics of filing his piece would be a problem - he simply couldn’t get to work.

"Physical restrictions prevented pedestrian movement from one locality to another. I tried to reach the Network 18 office, located in Dalgate, from Rajbagh where I was staying,” he says. “After being turned away from the checkpoint multiple times, I managed to gain a pass and reach my office. I met the broadcast team and found that they were also looking for me. Then, the OB-Van engineer helped me get in touch with my editor, and I told him I had written a 1,600-word piece.

“He suggested that I narrate it to him, and he would write it down. However, the OB-Van engineer suggested that we get the story printed from office computers, and he would record a video of it and send it across. I sent a few more stories to my editor the same way."

Meanwhile, other journalists in the region were also discovering that they would have to find creative ways to do their jobs if they were to continue working under the new restrictions.

Yash Raj, currently interim editor of The Kashmir Walla (he was assistant editor in 2019), says: "In the first week of the 2019 clampdown, not even the government-provided internet services were available. The only working line was at a market near Humhama Airport in Srinagar.

“There would be queues of journalists waiting to establish contact. The same place also has landline telephone services. So, I called my friend and dictated a 700-word story to her over the telephone, including the punctuation and formatting. Then, I shared my email ID and password with her and asked her to send it to my editor."

As if journalism wasn’t already a tough job in Kashmir, it had just got a whole lot harder.

One of our team members at Kashmir Walla would fly to Delhi and collect all the information needed to complete the story. This would happen every week

Yash Raj, Kashmiri journalist

Information has become the most valuable resource in the contemporary world. With the rise of innovative technologies, especially the Internet, users worldwide are churning and consuming information at ever-increasing rates. According to the Digital 2022 Global Overview Report by DataReportal, there are 5.31 billion (67.1 percent) unique mobile phone users, 4.95 billion (62.5 percent) internet users, and 4.62 billion (58.4 percent) active social media users in the world as of January 2022. The result is a flow of information where producers and consumers of information are indistinguishable. We are “prosumers” now.

More than half of the planet is online. Owing to its ubiquitous nature and ease of use, the Internet has become the most popular source and medium for accessing and disseminating information.

A report by technology group DOMO entitled Data Never Sleeps 9.0 offers a glimpse into the amount of information accessed and produced in a single minute on the Internet. Google conducts 5.7 million searches, 12 million IMessages are sent, 2 million “snaps” over Snapchat and 575,000 tweets are posted. People are living and sharing their lives over the Internet.

It is no surprise, then, that when the internet gets switched off, life and work for large numbers of people comes to a grinding halt.

Internet shutdowns 'on the rise'

This is what happens when a communications blockade is imposed, resulting in internet blackout or reduced internet speed, censorship (only whitelisted websites and apps can be accessed), telecommunication gag (mobile network and landlines are disrupted), physical obstructions of pedestrian and vehicular movement and curfews - or a mixture of the above. In the recent past, all these forms of information blockades have also been imposed simultaneously, resulting in a total communications gag in some places.

Internet shutdowns affect lives drastically. According to Access Now, an international organisation which advocates for digital rights of internet users, an internet shutdown is defined as "intentional disruption of the Internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information".

The data on internet shutdowns from 2016 onwards shows that the instances of internet shutdowns have been on the rise. According to the annual reports published by Access Now, the number of internet shutdowns worldwide since 2016 has been as follows:

In 2021, Access Now documented 182 instances of internet shutdowns imposed across 34 countries. The length of shutdowns was also longer. A single instance of shutdown may last for days, weeks or even months.

Where have internet shutdowns been imposed?

According to the #KeepItOn 2021 report, a campaign started by Access Now to “fight the rising tide of internet shutdowns", Asia and Africa are the most internet-shutdown-affected regions. Countries where they have occurred include: Ethiopia, Uganda, Eswatini, Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, South Sudan, The Republic of Congo, Zambia and Gabon. In Asia, countries which imposed internet shutdowns include India, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia and China.

In 2021, the Asia-Pacific region witnessed the most internet shutdowns - 129 -, with India topping the list at 106. Out of these 106 instances, 85 occurred in Kashmir.

Several Central Asian countries have seen internet shutdowns, while in Latin America and the Caribbean, Cuba is the only country that has faced an internet shutdown. Some Middle Eastern and North African countries have also suffered internet cuts.

Russia is the only Eastern European country to block access to the Internet. The country also launched a bold cyberattack in the early days of its invasion of Ukraine. The assault resulted in the disruption of services of satellite internet users throughout the region. However, SpaceX founder Elon Musk came to the rescue with his Starlink satellites and rebooted the region's internet services.

However, not every region has its Musk to ride to the rescue. The four most prolonged recorded internet shutdowns in the world as of 2021 are:

The duration of these shutdowns was so prolonged that they extended to the following years. In Tigray, Ethiopia, the internet blockade is still in effect.

In October 2021, Srinagar’s downtown area - the most densely populated area of the city, witnessed frequent internet cuts for almost a month. The internet remains suspended from 7am to 11am and from 3pm to 10pm.

‘Throttling’ and regional blockades - how internet shutdowns are imposed

In 2021, the most common form of internet shutdown was the blocking of mobile internet access. In some instances, specific communication platforms are blocked. These platforms are usually social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter through which members of the public can express opinion, anger and stage protests. In some cases, email services were also barred.

New tools and techniques have been developed which ensure disruption of the flow of information. “Throttling” is a technique by which the internet speed is deliberately reduced so that it becomes increasingly difficult for users to access and share information. Although internet services may be functional in these instances, throttling can severely hamper information seeking. Most websites and information sources online are designed to run on high-speed Internet and cannot be easily and readily accessed on reduced internet speed.

Governments use internet shutdowns 'during protests, social or political unrest, elections, and even during active conflicts often as a means of asserting or maintaining power'

Access Now, campaign group

Another form that Internet shutdown can take is regional internet shutdowns. In this scenario, the internet services covering a specific area are severed. In another variant of internet shutdown, internet access is denied to certain people.

Why are internet blockades imposed?

In 2021, countries including Cuba, Chad, Iran, Myanmar, Pakistan and Sudan imposed internet shutdowns either partially or entirely because of popular protests. On October 25, 2021, the military shut down the Internet in Sudan while it carried out a military coup.

Internet services are becoming a prime casualty in regions engulfed in war and conflict. Data collected from conflict-torn regions like Yemen, Gaza, and Syria reveals that Internet infrastructure is becoming an active target in conflict zones (#KeepItOn).

Myanmar, which also underwent a military coup, observed the shutting down of multiple communication channels in February 2021. The region also witnesses other forms of information blockades such as the whitelisting of “acceptable” websites, regional shutdowns and censorship.

During an election, access to information is paramount, and imposing an internet shutdown during this time is detrimental to democracy. Several countries, including Iran, Uganda and Zambia, have imposed internet shutdowns due to elections.

Fake news and misinformation are among the most frequently cited reasons for imposing an internet shutdown. However, shutdowns can also have the reverse effect and further propagate fake news and misinformation, as has been seen in Sudan and Myanmar.

Information blockades in Kashmir

Kashmir has seen unprecedented instances of information blockades over the past decade. The region recorded its first Internet shutdown in January 2012, and since then, it has been prone to frequent impositions. According to Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC), since 2012, Jammu & Kashmir has undergone the highest number of internet shutdowns than any other region in India. According to Internet Shutdowns, a website run by Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC) which tracks internet clampdowns in India, Jammu & Kashmir has counted 400 internet shutdowns since 2012, with the most recent occurring on April 9, 2022, in the southern districts of Kashmir.

The frequency and intensity of internet shutdowns in Indian-controlled Kashmir increased post-2016, following the killing of rebel fighter Burhan Wani and the protests resulting from his death which sparked widespread unrest. In the aftermath of Wani’s killing, a marginal increase was seen in the insurgency and counter-insurgency activities across the valley, eventually leading to Operation All-Out. Operation All Out (OAO) was a joint offensive launched by the Indian Army, CRPF, Jammu and Kashmir Police, BSF, and IB (Intelligence Bureau) in 2017 to counter rebel activities in Kashmir.

Such brazen exercise of information blockades, as we saw in 2019, provides more room for rumours

Kashmiri journalist AA who wishes to remain annonymous

In the lead-up to that, however, mobile internet services were suspended 10 times in 2016. The year witnessed the second-longest internet shutdown in India, lasting for 133 days (July 8 to November 19, 2016).

In November 2016, only postpaid mobile internet services resumed. Pre-paid mobile internet services only became operational nearly two months later, on January 27, 2017. In 2016, following the death of Burhan Wani, the state government initially stopped 3G and 4G internet services. After some months, internet services were restored, but 22 social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp were blocked as the protests in colleges and universities across the state refused to fizzle out.

The Internet was completely restored the following year - 2017. During 2017 and the years that followed, instead of blocking mobile internet services across the valley or banning social networking sites, the state would instead block services in specific areas where an encounter between security forces and militants was taking place.

The longest-ever internet shutdown in the history of democracy

The internet blockade which began in August 2019, however, would become the longest ever to have taken place.

In the lead up to it, Kashmir had become overwhelmed by rumour and speculation such as: a possible war with the neighbouring country, repeal of Article 35A which granted autonomous status to Indian-controlled Kashmir, execution of separatist leaders who were in prison, and even that the Prime Minister was going to hoist India’s flag from Kashmir's Lal Chowk on Independence Day instead of the Red Fort.

But before this “information anxiety” could be quelled, it was replaced with an information vacuum which did nothing to allay it.

People in Kashmir were seen in long queues outside petrol pumps, ATMs and Pharmacies, stocking up on essentials.

On August 4, 2019, a blanket communication gag was imposed across Jammu and Kashmir. On August 5, 2019, the Indian Government rescinded Kashmir's autonomous status by abrogating Article 35A.

There were so many stories that we were never able to explore. There were many stories we had an idea about, but we couldn't pursue them

Aakash Hassan, Kashmiri journalist

What came next was the most prolonged communications blockade that the world had ever seen - covering both internet communications and physical meetings between people. Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), which bans an assembly of more than four people at one place, was put in place in large parts of Srinagar. The only things working were the set-top boxes that were telecasting sessions of the Indian Parliament where the bill to repeal Article 35A was presented.

Mobile services, excluding internet services, were resumed for post-paid subscribers only (just 7.3 percent of mobile phone users - the majority use pay-as-you-go prepaid services) on October 14 at noon, after 72 days of a total communication blockade.

Having blocked 4G high-speed internet, the Government only restored 2G internet services, with initially only 301 whitelisted websites functional in January 2020. In February, 1,000 more websites were added to this whitelist but even those websites were not working properly because of the reduced speed.

Kashmir is not the only region in India to have suffered from internet shutdowns. There have been 641 internet shutdowns in India since 2012. Rajasthan (82), Uttar Pradesh (30), Haryana (17), West Bengal (13), Gujarat (11) and Bihar (11) are some of the regions where internet shutdowns have been imposed. It is worth mentioning that these are instances of internet shutdown, not the number of days an internet shutdown lasted.

In West Bengal's Darjeeling alone, a 45-day internet shutdown was imposed in 2017, while in Nawada, Bihar, a 40-day internet shutdown ensued in 2017.

‘We had to fly to Delhi to get information we needed’

An information vacuum is formed during an information blockade, which opens the door for fake news, disinformation and misinformation to run riot.

"Such brazen exercise of information blockades, as we saw in 2019, provides more room for rumours,” says Kashmiri journalist AA, who was working as a sub-editor at one of the local daily newspapers in 2019 in Srinagar and wishes to remain annonymous. “When the institutionally approved mediums of information are blocked or censored, unverified information goes into the public domain and creates more problems."

A journalist's job entails telling people what they cannot experience directly. A journalist makes remote events observable and meaningful to the audience. They do this by providing authentic and reliable information to the audience.

But, during blockades, journalists were also facing an information void. "There were stories with a tremendous scope that demanded to be explored in-depth, but their scope got restricted due to lack or limited access to information,” says Aakash Hassan, who was working as a multimedia journalist for Network 18 in 2019 and is currently working as a freelancer.

“Concurrently, there were some situations where you were able to get hold of some information, but you could not get enough information to justify your story to the editor. There were so many stories that we were never able to explore. There were many stories we had an idea about, but we couldn't pursue them."

"I had to be very selective with my choice of story ideas,” says Bisma Bhat, a reporter working on a local daily newspaper. The criterion was usually importance but also do-ability."

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), notes that internet shutdowns prevent journalists from doing their jobs, curbing the freedom of the press. Depending on the level of an internet shutdown, a journalist's job can, at best, be challenging and, at worst, impossible.

"Any restriction on the mobility of journalists amounts to curbing freedom of the press,” says Kashmiri journalist AA. “Journalists were not allowed to move, and an atmosphere was created where they were afraid to move. There were reports in 2019 about journalists being harassed, in certain cases, even physically beaten. All such acts are forms of restriction on the profession of journalism."

Journalists were not allowed to move, and an atmosphere was created where they were afraid to move

Kashmiri journalist AA, who wishes to remain annonymous

Yash Raj, who was working as assistant editor at The Kashmir Walla in 2019 and is currently serving as the weekly's interim editor, adds: "When you write a news story, you spend a significant amount of time researching to get the facts right. But, during the information blockade, there would be details in your story you couldn't verify or mention, such as figures or legalities about an Act, Bill, or a Law such as the infamous Public Safety Act (PSA). We would leave blank spaces in the story. Then, one of our team members at Kashmir Walla would fly to Delhi and collect all the information needed to complete the story. This would happen every week."

Similarly, journalists working in Kashmir for media organisations outside the region would also send their stories to editors and convey the missing parts. "So, while writing, if I could not verify the facts, I would make notes in parentheses like (Please cross-check for this source, please verify). Then, people at the editorial desk would fill in those details," says Hassan.

Back to ‘old school’ ways of journalism

"2019 was an extraordinary situation, never seen before by journalists in Kashmir,” says Quratulain Rehbar,a freelance multimedia journalist who was working for The Kashmir Walla in 2019.

“It was unprecedented, especially when you consider how important a tool the Internet has become for journalists. We had to go back to the old school ways. Yes, we still have to travel to meet our sources, to be at meetings, events, and appointments. But, in 2019, journalists travelled to find sources and ideas."

Information blockades affect the kind of story that journalists can undertake as well. The information blockade of 2019 was a significant event owing to its singularity and duration - so much so that it became the news.

"There were many story ideas planned that I had to leave behind because something bigger had happened that shifted the priorities,” says Hassan. Ideally, a journalist would work on multiple stories simultaneously, but in 2019, there was no scope to do so because of the physical restrictions and communication blackout."

We had to go back to the old school ways. Yes, we still have to travel to meet our sources, to be at meetings, events, and appointments. But, in 2019, journalists travelled to find sources and ideas

Quratulain Rehbar, Kashmiri journalist

During a total information blockade, a journalist cannot inform the public. They cannot be a watchdog. Journalists cannot report on the day's developments or break any story because they either don't have the information or lack the publishing tools. Further, it also affects core journalistic principles, such as credibility, because a journalist cannot cross-check the information he comes across.

Tips for journalists working under information blockades

Bear witness

Journalism has been called the "first draft of history". As a journalist, you may be witnessing and documenting history as it unfolds.

While he was working under a blockade in Kashmir in 2019, Hassan says: "I was able to access a small portion of the city from Rajbagh to Lal chowk, which is the city's centre and important in many ways. I thought of narrating the mood on the ground. I was just describing things and contextualising what I was seeing with what used to be. There were no interviews."

Although it has always been the priority of journalists to disseminate information, sometimes it is not possible to do so.

"In 1990s Kashmir, some stories were not published and were not made public, they were kept beneath the curtains, but they re-emerged,” says Kashmiri journalist AA. “The atmosphere wasn't conducive for such stories then, but the stories came out some 10 to 12 years later. Not all stories are reported in their time; that has always been a tragedy. This can be because of a lack of attention and understanding or because the risk of writing and publishing such stories is huge. The job of a conscious reporter is to keep a record, a diary."

Think outside the box

Media organisations, especially those located outside the zone where information blockade is imposed, can aid their employed journalists and help them narrate the stories they witness.

As Hassan did when working for The Kashmir Walla under the 2019 information blockade when he could not reach his office, make use of unconventional means to communicate. Friends can also be saviours at such times - as proved the case for Raj, mentioned earlier in this piece. They can help you get the information you need and disseminate it.

Keep moving

If information is not reaching you, you will have to travel to it. The telecommunication gag coupled with physical obstruction creates mini information vacuums locally, where people living in a particular block, town or district don't know what's happening in the neighbouring one. A journalist needs to make journeys - a lot of them - during information blockades.

"After some time, you run out of ideas. You can't keep sitting where you are and narrate what you are seeing and hope to interview people who may pass by,” says Hassan. “You need to be on the move. I and some journalists decided to visit rural areas as there was no news coming from such regions. We created a proper schedule to visit all the districts.

“During one of these exploratory journeys, I found a critical shortage of medicine in Uri. Similarly, in Sopore village, I discovered that people associated with horticulture, especially the apple traders, were facing huge losses." Both of these issues made important news stories.

Be persistent

Gaining access has always been paramount for journalists. Information blockades restrict access on multiple levels. Physical obstructions restrict movement from one area to another. Some checkpoints block access to offices, sources and areas you want to explore.

We would send reporters in pairs to places away from Srinagar because even a small logistic glitch, like a vehicle running out of gas, could lead to a disaster

Yash Raj, Kashmiri journalist

If journalists cannot find their way around these physical barriers, their job can become impossible. "To be honest, there is no sure way to beat it,” says Rehbar. “You have to be persistent. Carry your ID cards along that may open the doors. If that fails, try different timings. Many journalists have managed to pass physical blockades at dawn, for example."

Being in touch with fellow journalists is helpful for getting information about how to gain access to an area.

Strike up conversations

In the absence of technology due to information blockades, journalism in regions like Kashmir has been pushed decades back. The usual means of getting stories are unavailable.

Journalists cannot "hear" about newsworthy events because everyone is disconnected. So, strike up a conversation with a passer-by; the reason they are out of their house may be a newsworthy story.

"The Internet was a very helpful source for me to generate ideas. But, in 2019, since it was not available, you had to find alternative methods to get newsworthy ideas,” says Rehbar. “I would take walks to Lal Chowk almost every day. During one of the walks, I noticed a woman in her 60s who looked agitated. Upon talking to her, I found her granddaughter was getting married, and she had come to Lal Chowk to get a shawl she had commissioned from a shop. Although this may not have been a newsworthy idea, it prompted me to gauge the broader question of how information blockades affected women in Kashmir."

The woman further explained that during the information blockade, people living around Lal Chowk would come out in the evening to take a breath of fresh air along the banks of Jhelum. This gave rise to another important story.

"I interacted with parents of school-going children to find how the blockade was affecting kids who had to stay home."

Travel in packs

Fieldwork is an integral part of journalism. Ideally, journalists cover stories independently. However, it is a good idea to travel in groups during blockades for security reasons.

"In a clampdown scenario, the story ideas we undertook were mostly based around Srinagar. The idea of sending our reporters to other districts was always a risk,” says Raj. “So, we would send reporters in pairs to places away from Srinagar because even a small logistic glitch, like a vehicle running out of gas, could lead to a disaster. Further, there was the fear of being harassed or beaten at checkpoints."

It is especially challenging for women journalists to work during blockades. "I had to face some obstacles which my male colleagues did not,” says Rehbar. “They could travel, and some of them even managed to get internet access during the initial days as a landline service was working somewhere around the airport. I could not travel because I was scared to do it alone and because I did not have my own vehicle, so I would look around for ideas that were close to where I was residing. And, when I did travel, it was always in a pack."

Collaborate

Journalism is a very competitive profession. But, situations like prolonged information blockades are unprecedented.

"The focus was to get the word out, to pitch the stories to national or international media platforms,” says Raj. “But, how would we reach them? When the Government set up the media center in Lal Chowk, Srinagar reporters could not log in to their email accounts because they required two-step verification, and their phones were not working. So, the reporters created new email IDs, but they did not have the emails of their editors or the organisation they wanted to pitch their story to. So, a collaborative effort was the key in such times, even if journalists were from different organisations. Anybody working with a particular editor would share their emails. Nobody ever said no."

Anticipate where stories may develop

One of the often-cited justifications for imposing information blockades is to curb the spread of misinformation and rumours. But, imposing a blockade can further escalate the spread of misinformation.

As a journalist, there is no way to verify what you hear during information blockades, especially if the "information" is about remote areas. You need to develop a journalistic sixth sense.

“Rumours were flying around about people being injured in clashes, but there was no way to verify it,” says Rehbar. “I started visiting hospitals. I anticipated that if clashes had erupted somewhere and people got injured, they would be brought to the hospital. I visited the hospitals for a week and documented everything that I saw. That was my first story during the blockade."

Using a similar approach, she says, she also managed to do a story about how information blockades affect the behaviour of children stuck at home. You need to develop foresight and anticipate where information might come from.

Retreat and regroup

Journalists, whether affiliated with an organisation or working independently, need to regroup at a place where they can exchange information and collaborate. During an information blockade, journalists can create their information repository at these meeting spots.

From here, information collected by all the journalists can be distributed through word of mouth. These meeting points also become a place where journalists and editors can meet and exchange their work and feedback.

"After I finished fieldwork, I would visit the Press Club [in Srinagar - now closed], a rendezvous point for journalists, and write my stories. My editors would also be there, and I would file my story in a pen drive," Rehbar says.

Since the Press Club was forcibly taken over by pro-Government journalists and then shut down at the start of this year, journalists in Kashmir have been forced to find new safe places at cafes and each other’s homes instead.

Keep on keeping on

Since 1990, journalists in Kashmir have been assassinated in their offices and many times imprisoned, beaten and “summoned” by the police. But still they go on.

Journalists in Kashmir have been carrying out their journalistic duties during some level of information blockade or another for more than a decade now. As a result, their work has been published, acknowledged and awarded internationally.

After I finished fieldwork, I would visit the Press Club, a rendezvous point for journalists, and write my stories. My editors would also be there, and I would file my story in a pen drive

Quratulain Rehbar, Kashmiri journalist

For their coverage of the 2019 information blockade, three Kashmiri journalists, Channi Anand, Mukhtar Khan, and Dar Yasin, working for Associated Press (AP), were honoured with the Pulitzer Prize (2020) for feature photography. Their work showcased the lives of the people of Jammu & Kashmir during the shutdown. The Pulitzer was awarded to the trio "For striking images captured during a communications blackout in Kashmir depicting life in the contested territory as India stripped it of its semi-autonomy."

In 2022, Sanna Irshad Mattoo, a photojournalist from Kashmir, received the Pulitzer Prize as a part of the Reuters photography staff, including Adnan Abidi, Amit Dave, and (late) Danish Siddiqui. Their work focused on the impact of COVID-19 in India.

Indeed, the 2019 information blockade was still in effect when coronavirus engulfed the world. The valley's mobile internet services were only functional at reduced 2G speeds at the time. Pre-paid mobile phones, used by more than half of the population, were banned when COVID-19 restrictions were imposed in Kashmir.

Yet, journalists in Kashmir still managed to do their job and did it efficiently.