Harrowing Experience and Determination

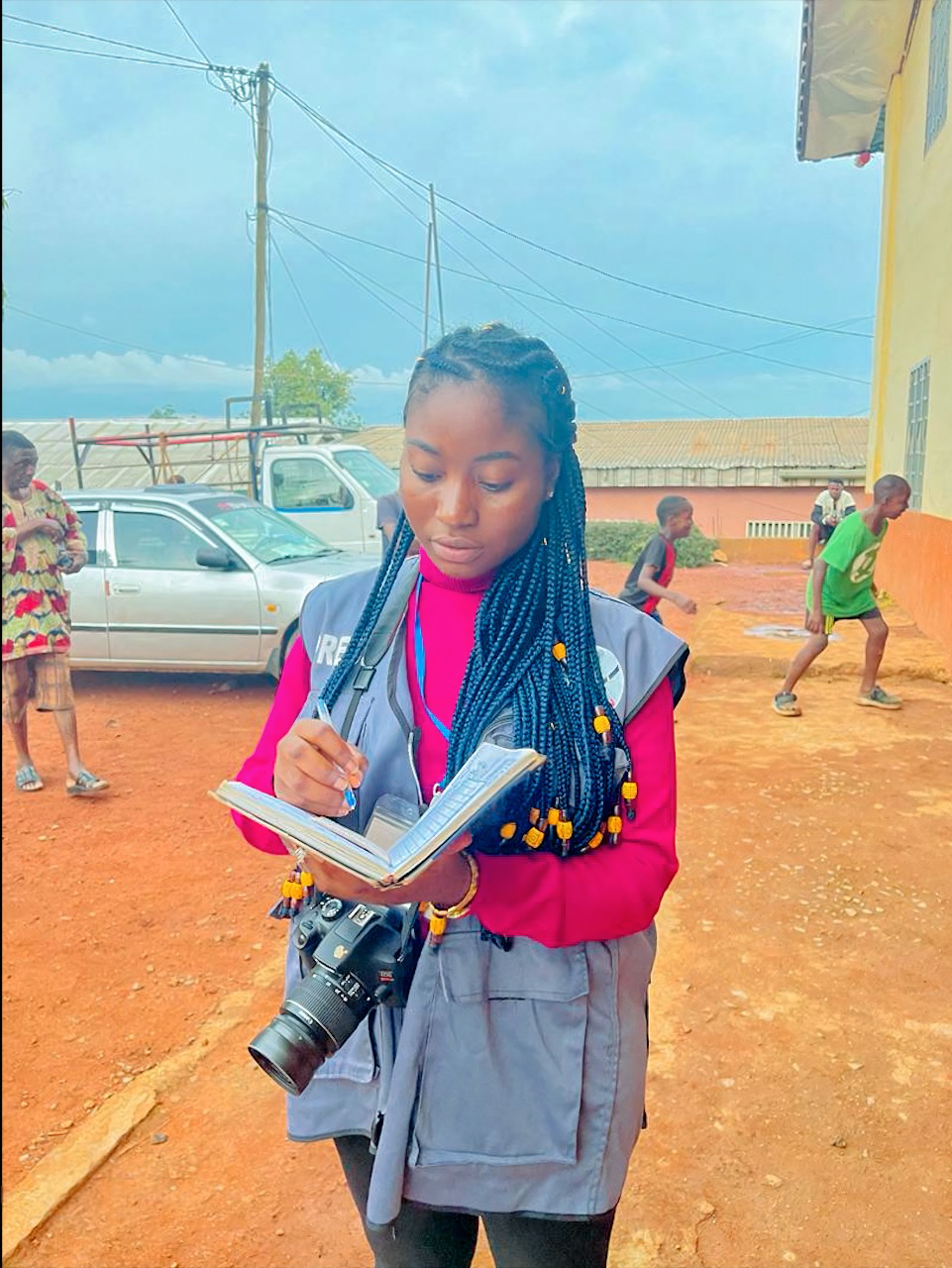

Enjoh's experiences, including narrowly escaping death when her home was set on fire and surviving an attempted rape from gunmen as she sought safety, have made her even more determined to shed light on the plight of the people affected by the ongoing armed conflict between Cameroon's government and separatist movements, which is known as the Anglophone Crisis.

The conflict began in 2016 when teachers and lawyers went on strike to protest the conditions of the Anglophone minority in a Francophone-dominated country. Since then, it has escalated into open warfare.

Bruised by the conflict, Enjoh has become a fierce female journalist who is willing to go the extra mile to highlight the sufferings of people, particularly women and girls.

Living at the epicentre of an armed conflict and having been bruised by the very crisis, Enjoh knows the challenges of reporting in and from the war-torn zone better

Akalambi Clare Enjoh is a freelance female journalist from Cameroon based in Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest Region, the epicentre of warfare, where she’s reported for 8 years, just as long as the crisis has lasted.

“I was in one of the houses that was set ablaze in my neighbourhood—Mbengwi Road—in 2021. Though I managed to escape the burning house, I was caught by gunmen and almost raped,” recounts Enjoh adding that though she’s healed from the traumatic experience, she committed to combatting GBV and promoting mental health support, especially for women and girls affected by the crisis.

Challenges of Reporting from a Conflict Zone

Enjoh’s journey to journalism was a smooth ride but didn’t last for long. “I have been practicing journalism for about 8 years, starting from my university days. By then, the crisis had just begun, and things weren’t as bad as they are now. The profession seemed straightforward—a student with a microphone against the world. I was strictly under the guidance of my lecturers, station manager and programme manager of our school radio, UBa Voice, FM 91.5,” says Enjoh.

However, "this path hasn't been without its challenges", she says. Upon leaving school and with the crisis persisting, she realised journalism wasn’t exactly what she thought it to be. Enjoh volunteered in a few media houses, and it was then that she encountered the complexities of the field, particularly the rise of "Gombo Journalism (a term used to describe the practice of journalists accepting monetary or much more incentives in exchange for favourable news coverage or to suppress positive information). This realisation led her to embrace freelance journalism, where she says she could uphold the ethical standards of journalism that she learned at school.

I was in one of the houses that was set ablaze in my neighbourhood—Mbengwi Road—in 2021. Though I managed to escape the burning house, I was caught by gunmen and almost raped

Reporting in and from a crisis-hit area is an uphill task. According to Reliefweb, from covering wars to protest movements, female journalists working in conflict zones take immense risks in the name of freedom of information. Fighting government censorship, retaliation and deconstructing disinformation is a daily challenge for many.

Living at the epicentre of an armed conflict and having been bruised by the very crisis, Enjoh knows the challenges of reporting in and from the war-torn zone better.

“Securing many assignments, especially as a solo practitioner, has been tough. In general, accessing sources is a constant struggle. Most areas during the crisis have become no-go zones due to insecurity. To make matters worse, the sources who are willing to defy the odds to speak sometimes demand payment or withhold information [especially for fear of repression from the warring factions]. Often, I contact sources and they promise to respond on a deadline but end up not responding,” says Enjoh

Orla Tita Nki, a female Journalist with Cameroon’s State Broadcaster, CRTV (Cameroon Radio and Television), has had similar experiences living and reporting in the crisis-stricken Northwest Region, where she’s spent 10 years, seven of them in the lifetime of the armed conflict.

Bruised by the conflict, Enjoh has become a fierce female journalist who is willing to go the extra mile to highlight the sufferings of people, particularly women and girls

“I started work in the Northwest during the early days of my career when there was no crisis. It was exciting, and you had people ready to grant interviews [at every request]. Access to sources was very easy. Unfortunately, with the coming of the crisis, access to resources has become a nightmare. Everybody is on the alert and very cautious. They shy away from the media—or worse, the state media, says Nki.

Mbuh Stella, a backpack female journalist, says news sources are equally drying up as more and more people are displaced while others are taking sides in the conflict, thereby disinformation and fake news thrive.

There’s no Freedom of Information Act or Right to Information Act in Cameroon. That alone, in the past, made it difficult for journalists like Enjoh, Nki and Mbuh to access information. Today, the wake of the crisis has just further compounded the issue. For example, having the exact number of people killed in the lifetime of the crisis is likened to having an elephant go through the eye of a needle.

An Upsurge of Sexual Harassment

Besides the perennial problem of accessing information and sources, demands for sexual favours are another major challenge female journalists are facing daily. “I’ve had male sources I tried interviewing ask me for sexual favours. One went as far as grabbing my buttocks, which I warned him against and threatened to sue him if he continued. Regrettably, this type of demand is an issue female journalists like me have had to face often,” says Enjoh.

I vividly remember another instance involving a lawyer for a story on gender-based violence in Cameroon newsrooms. I was writing for Africa Women in Media's (AWIM’s) GBV Magazine. The [male source] lawyer I had to interview for a story kept postponing the interview. Afterwards, he invited me to his office for the story. It sounded suspicious and my guts didn’t sit well with it. So, I tried convincing him to respond on the phone, but he didn’t. Later, he asked for payment before he could consider responding to the questions. I simply stopped texting him and got to another lawyer, who responded to all the questions without asking for any favours, she explained.

Nki on the other hand, says that, as a female journalist, working in the world of men is not very easy. “Sometimes you meet organisers who think they can just make their way through because [I’m] you’re a woman. As a female journalist, they believe they should have an affair [sex] with you in exchange for information. They sometimes harass you, bug you, and ask for your private contacts.

Female journalists not only have to deal with sexual harassment but also face low recognition from male colleagues and verbal threats to their lives. “I have faced numerous threats from parties [warring factions] involved in the conflict. I was once tagged as a separatists’ spy by soldiers, while the separatists on their part have tagged me too—because I found myself as a journalist in areas where many will not dare,” says Mbuh.

Securing many assignments, especially as a solo practitioner, has been tough. In general, accessing sources is a constant struggle. Most areas during the crisis have become no-go zones due to insecurity

Mbuh describes the quest for recognition from male colleagues as a daily challenge. As a camera operator, journalist, and video editor, I've faced situations where I had to assert my competence to my male colleagues to be considered for certain assignments. There have been moments when colleagues would dismissively say, “She’s a woman,” or “they are always too weak and slow to complete tasks.” I had to rise above these remarks and demonstrate that my gender does not limit my capabilities. I've learned to embrace my colleagues and to ensure they see me as a journalist, not merely as a woman in journalism.

Limited Accessibility

Another major challenge Enjoh, Nki and Mbuh are confronted with is physical access. Accessibility to some areas—considered red zones is a no-go for us. Our coverage of the region is now very limited. When I started off practicing in the region, besides the quest to make the media a place for the community—where every voice is heard or represented—I saw my job as a unique opportunity to discover the region. I was ready to hop onto the next cab to go on coverage in any part of the region. But today, it's a different ball game. Practising journalism without and in crisis are two different pictures, says Nki.

Upon leaving school and with the crisis persisting, she realised journalism wasn’t exactly what she thought it to be. This realisation led her to embrace freelance journalism, where she says she could uphold the ethical standards of journalism that she learnt at school

Keeping the Profession Alive

In light of the current situation and the constantly shifting nature of the crisis, journalists are compelled to practice self-censorship, and at times, they must resort to it. "I have chosen to steer clear of reporting on matters that could endanger my life or that of my sources. We cannot take such risks anymore. Unless I am under military protection, I avoid areas that are off-limits. Moreover, nowadays, I focus more on health and environmental stories, unlike before when I covered a wide range of topics. I prioritize these areas because I know experts [sources] can speak freely without fear of repercussions. Safety comes first," Nki explains.

As a coping strategy to circumvent the challenges and still bring to the fore the daily struggles of women and girls in the armed conflict, Enjoh has learned to ply her trade cautiously.

“I've learned to assert my boundaries, avoid one-on-one meetings in closed settings [with male sources], and always have backup contacts prepared to step in if I sense any form of sexual advances or harassment,” says Enjoh. In addition, she’s taken on Gender-Based Violence and Mental Health Wellness Activism to help women and girls recover from trauma. To her, the activism part of work is a form of therapy. “I am equally a GBV and mental health activist because of an encounter I had during this crisis that severely impacted my mental health. Because of my experience, I've committed myself to combat GBV and promoting mental health support,” states Enjoh.

Mbuh on her part, says, “As a coping strategy, I got myself a smaller device because people now perceive cameras differently and a journalist can easily be targeted and harmed. Some of my experiences are tear-provoking as I watch children die and houses razed to ashes”.

Training is a Dire Need

According to the United Nations, journalists face a significant number of challenges in the field, including dangers to personal security and meeting their basic physical needs, as well as operating within an extremely complex information environment. Due to such risks, training on field safety in war zones for journalists is paramount, stresses the United Nations.

Similar to the United Nations, Nki believes that journalists, especially when reporting from crisis-affected areas, require training to manage the risks involved. Additionally, there is a need to support female journalists in conflict zones to guarantee their ability to continue reporting on critical matters.

“To help [us] journalists work effectively, we should be trained on field safety. Unlike other journalists who are trained and deployed to work in war-torn zones, the armed conflict just happened to us and we’re just dabbling to report without any training. Imagine going out with a military convoy to the war front and you don’t know what to say at the end of the operation or how to carry yourself during an attack or crossfire,” she says.