From working shifts in a casino to interviewing a farmer mauled by a tiger - life as a struggling Zimbabwean reporter.

In his final days, Robert Mugabe had become a monster.

After three decades in power, Zimbabwe’s ageing leader was positioning himself to contest the 2008 presidential elections. As Mugabe campaigned, Harare’s hyperinflation hit a record 79,600,000,000 percent. Prices doubled every hour. Most basic foodstuffs were running out, while industries closed daily. The introduction of the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) in 2002 threatened the existence of the media. For an aspiring journalist like me, it felt like there was no future in Zimbabwe.

At the start of 2008, Thomas, a boyhood friend, convinced me to leave the country. Citizens were leaving in their droves. Like them, Thomas wanted a new start. We had been friends since 1985, so we valued each other’s opinions and I decided to follow him. But first, we had to get passports, followed by visas for South African, processed in Harare. The process took a long time because of the number of people trying to leave the country.

I eventually arrived in Johannesburg full of hope for a brighter future. To me, a novice, the country seemed ripe with opportunity. In contrast with Harare’s comatose economy, skyscrapers rose everywhere, news-stands were well stacked with publications.

It didn’t take long for my illusion to shatter. In fact, locals were enduring high unemployment and crime rates. When I arrived, Philemon, another friend from Zimbabwe, let me stay in his single room, which he was sharing with another colleague. And, far from living their dreams, the majority of Zimbabweans who had come to Johannesburg like me, including Philemon, were working as street vendors - anything to get by.

Anything to get by

For a month, I searched for a job - any job. Even though I wanted to work as a journalist, I nevertheless walked into restaurants, supermarkets and bookstores to present my unsolicited resume. I leafed through newspaper job sections, pitching to various publications in an attempt to land a gig. The only time I got lucky was when my letter to the editor was featured in the Daily Sun. Meanwhile, I sold counterfeit clothing labels in parking lots or at traffic lights. Journalism had to wait for the time being.

In May, I relocated to KwaZulu-Natal, in the hope of finding a better job. Up until that point, I had worked as a horse groomer, before moving on to waiting tables in Nottingham Road in Kensington, where I was hired on a wage of R8 ($0.50) an hour. Sometimes I put a 12-hour shift, from 9 am until 9 pm, then retired to the storeroom-cum-bedroom. Alone, I penned more pitches, sadly they were all rejected.

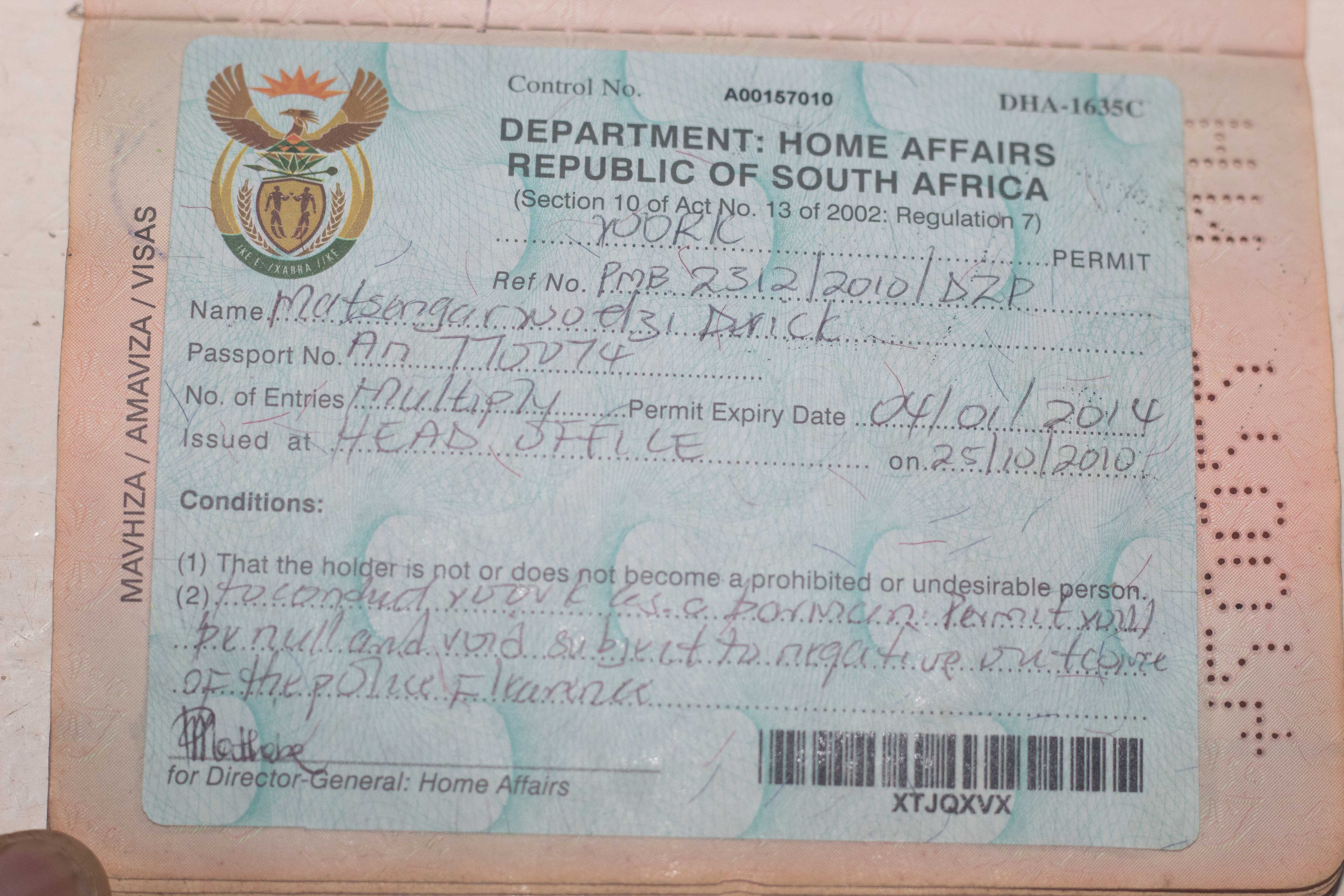

For months now, I had been working and staying in South Africa illegally, ever since the expiry of my initial visitor’s visa on August 18, 2008. The following December, I acquired a temporary residence permit through a middleman (not a legal means) - valid for a year - which allowed me to operate as a seasonal worker. It specified that: “Anyone who contravenes the purpose and/or conditions of this permit shall be guilty of an offence and liable of conviction to a fine or imprisonment.”

The illegal newsman

By law, I was an illegal immigrant, a candidate for deportation. But back home, I had a family to feed. The restaurant I had found work in was finally closed due to mismanagement. This time, I relocated to Pietermaritzburg in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal to enrol as a casino barman at the close of 2009. Inside the smoking section, the tips were better, though the shifts were demanding, especially the graveyard shifts, starting at 8 pm until 5 am the following morning.

In April 2009, a year before the World Cup, South Africa approved the Zimbabwe Special Permit (ZSP). Valid for four years, the work permits were for holders to live, study and work legally. But many were skeptical of the state’s intentions by issuing these permits.

“I think it’s a plan to arrest and deport us,” a friend suggested.

“Don’t be pessimistic. Some are going through the process,” I responded.

“I will only go after I evaluate the process,” he said adamantly.

I was among the first batch of applicants. Three weeks later, the permit was pasted inside my passport. The conditions read: “To conduct your work as a barman. Permit will be null and void subject to the negative outcome of the police clearance.”

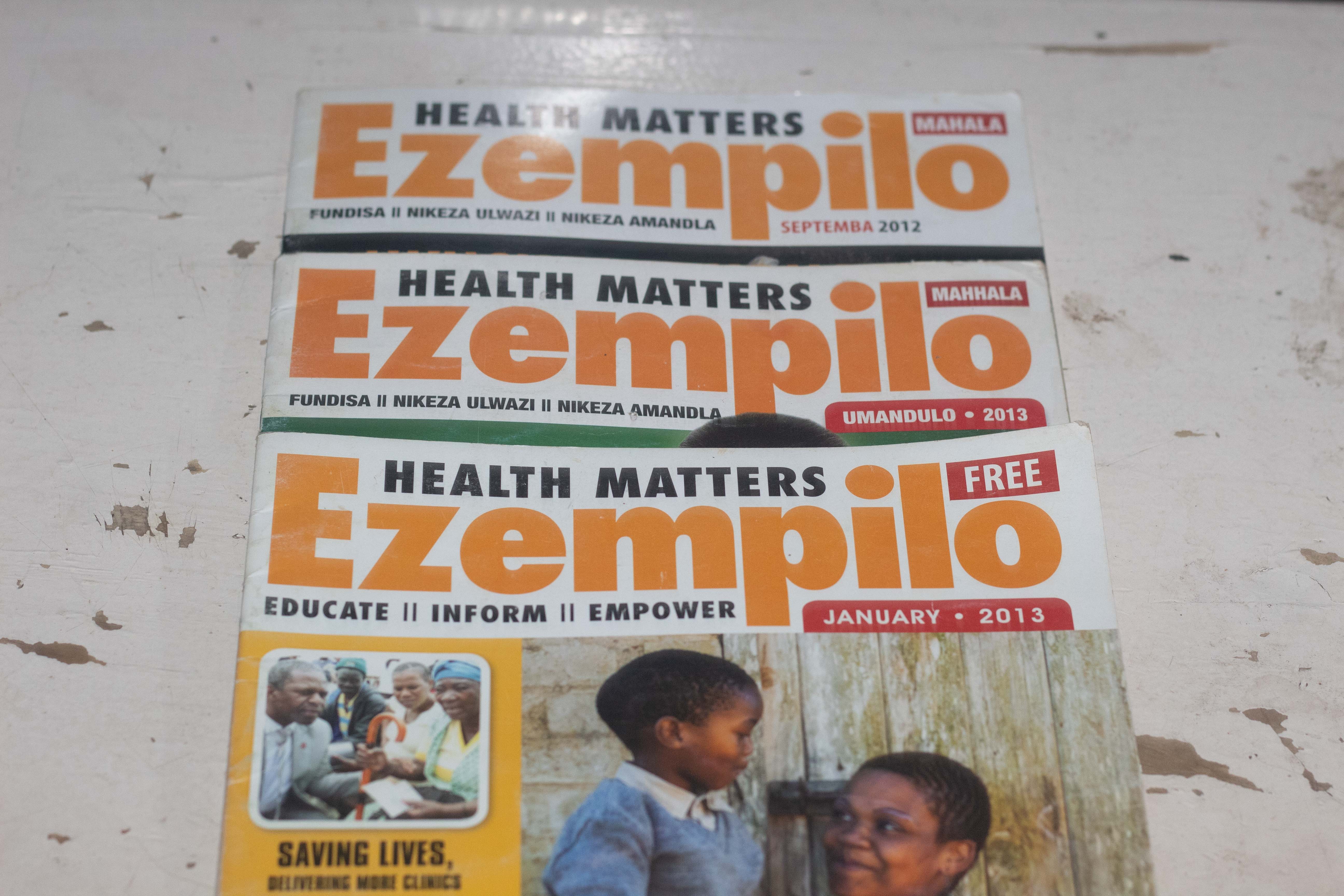

An online advert alerted me to a freelancing opening at a publication in 2012. I responded to the post half-heartedly. But a week later, I was hired to be a health writer for Health Matters (Ezempilo). A month later, I travelled to Benedictine hospital, nearly 200km from where I was living to interview a girl of 15 called Sanele Mathe, who had spent nine months in the intensive care unit of a hospital after surviving a bus crash.

It was my first proper story. “When I noticed the bus was going downhill, I remembered what I had seen in a movie,” the girl told me in IsiZulu. “I spread my body over my niece, then we slid under the seat.”

I scribbled my notes in English. “The bus plunged into a valley, spinning countless times, killing other people,” she added. Luckily, the two had survived.

'Call me Mr Long'

Back at the casino, bar clients repetitively interrogated me about my lengthy surname.

“Your surname is confusing. How do you pronounce it?”

“I am a Zimbabwean by birth, South African by default.” My diplomatic response drew a burst of laughter.

Pronouncing my surname - Matsengarwodzi - was difficult for many.

“You can call me Mr Long,” I jokingly told a patron.

This prompted a story idea, which I pitched to The Witness. Finally, in 2012, after four years of trying, my article titled: Long name blues was published in The Witness, a daily newspaper published in Pietermaritzburg. After my first article, I contributed regularly.

My second assignment for the paper was both interesting and shocking.

“Do you have any commitments tomorrow morning?” my editor asked.

“No plans yet, I will be off duty.”

She sighed in relief. “Good. Can you travel to Ulundi to interview a patient who was attacked by a tiger?”

No need to ask twice. “I will go, just give me the directions.”

Jack of all trades

Arriving at work that night, I prepared for a busy night. At 5:30 the following morning, I knocked off and by 7:00 I left to do the interview. When I arrived in Ulundi, 300km (186 miles) and three-and-a-half hours away by road, my interviewee, Bhini Khanyi, was waiting.

“Could you please tell us what happened on the day of the attack,” I asked.

“Early one morning, I went to the paddocks to find my missing herd of cattle,” he told me. “At that moment, my dogs started barking and I decided to check. Before I knew it, the tiger pounced on me, snapping clean my left arm. It was aiming for my head, but I covered it jealously.”

Alone and defenceless, he lay motionless. Blood oozed from the deep wounds. Alert villagers saved him just in the nick of time. After almost a year in hospital, he was discharged. Now he was forced to rely on his wife for almost everything. The attack caused permanent injuries. As for the tiger, some suggested it was a pet that had turned wild. I was equally pained and excited to conduct the interview.

It was not the first I would have to travel to. On my way to interview an expatriate nurse in rural Hlabisa, the car veered off the dirt road. A cord of firewood abandoned by the roadside miraculously stopped the car from accelerating downhill.

That same year, I finally left the casino bar to become a full-time freelancer, regularly contributing to three publications and with the promise of a full-time job at one of the magazines.

A day with the newsmakers

One afternoon in 2012, my son limped home from school, complaining of stiff, swollen joints. Hours later, he could barely walk. The piercing pain worsened. Carrying him on my shoulders, we headed for the clinic.

“He has signs of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). It is a systemic disease affecting the entire body, triggering inflammation of joints,” the doctor explained.

For the next three days, he was admitted to the hospital, where I stayed with him surrounded by nursing mothers. By the second day, he showed signs of revival. Except for a significant limp, the pain was gone. Our three-day stay was hospitable, and on the third day, he was discharged. After consultations with my editor, I returned to interview the staff of the hospital. Still nursing their shock, the medical staff flocked for a group photo. The piece about our experience in the ward was featured by the health magazine.

An Africa Day commemoration piece headlined, Afropolitan Maritzburg, which I co-authored, was published on May 24, 2013. In the article, various foreigners shared their experiences of the country. For another business magazine, I was honoured to interview Big Nuz, the hottest Kwaito musical group then. Again, in KwaMashu, a crime-torn Durban township, where drugs exchange hands at will, I was assigned an interview with 94-year-old Motlanalo Ndlovana, a retired nurse. Despite her ripe age, she insisted on speaking in English. Like a model, she posed confidently for the cameras.

Homecoming

During my five-year stay in South Africa, I wrote out of love more than for any financial rewards. Finally, at the close of 2013, after years of trying to break into the media industry, I was hired as a reporter in Durban. When I asked for a letter of engagement, the publisher was frank.

“You are a foreigner; your permit does not allow you to work in the media. If I do that, I will put my company at risk of being deregistered or fined.”

With that response, I concluded I had overstayed my welcome. Before my passport and work permit expired, I finally departed for Harare.