A wave of anti-migrant sentiment is gripping South Africa and those journalists covering it, who are migrants themselves, have become a particular target

Kimberly Mutandiro’s passion for writing about the problems faced by refugees and migrants in South Africa has turned her into a figure of hate. A freelance journalist from Zimbabwe, Mutandiro, 38, herself moved to South Africa in 2008.

Her work has triggered a great deal of opposition - much of it online - not just because of the subject she writes about, but also because she is a migrant herself.

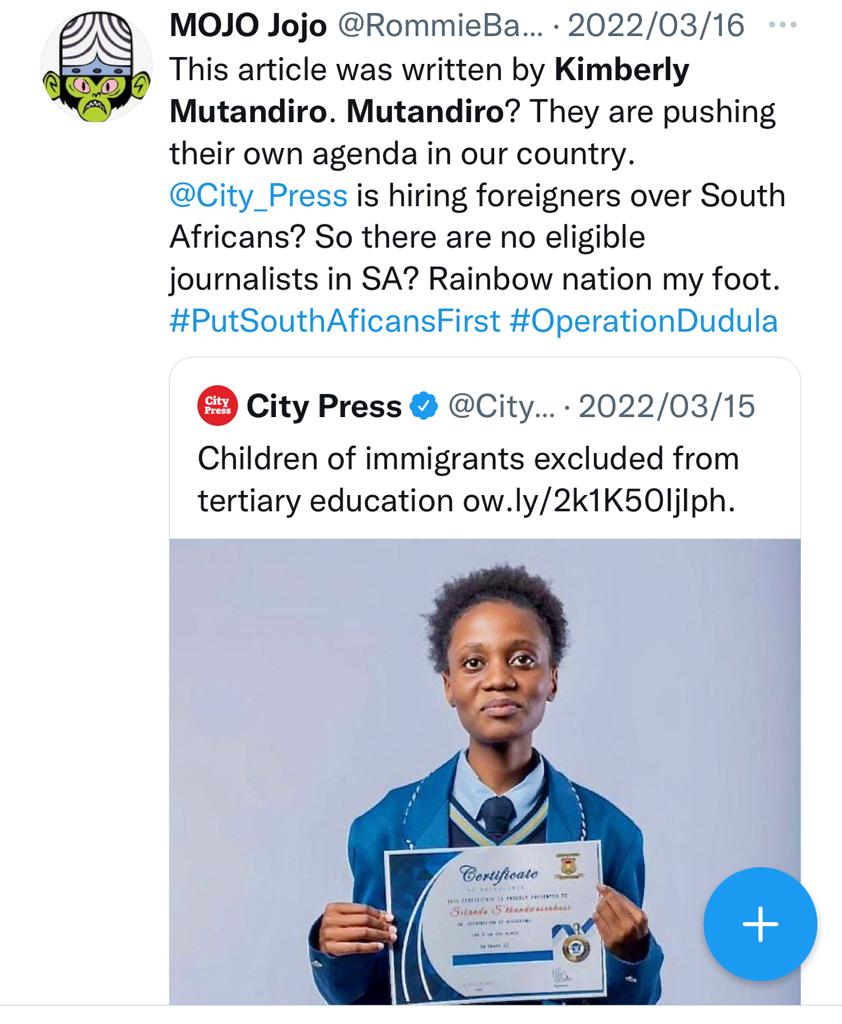

Her attackers, mainly often-anonymous social media accounts and some politicians, accuse foreigners like her of taking their jobs and committing crime. Earlier this year, for example, Fikile Mbalula, transport minister, claimed that “Pakistanis and illegal foreigners” were contributing to high unemployment rates in South Africa. Meanwhile, vigilante groups, such as those calling themselves “Operation Dudula” (which means “drive out”), have been carrying out violent attacks on migrant communities in districts of Johannesburg and other areas of the country. Their often-chanted slogan is “Put South Africans First”.

Advocacy groups have pointed out that foreigners only make up 8 percent of the working population, and claim that unemployment is caused by poor government policies. Sadly the scape-goating of migrants has captured the imagination of the country as a whole.

As a result, anti-migrant rhetoric and violence have escalated in South Africa in recent years. Since Mutandiro’s arrival in the country, violence against migrants and refugees, resulting in internal displacement of thousands of migrants and the deaths of others, including locals, have become a regular occurrence. For this reason, reporting on migrants has become fraught with risk.

“While covering immigration issues in South Africa, I have learnt how sensitive the topic is. It’s sad that the consequences of this hatred towards fellow Africans have escalated into death in many instances,” Mutandiro, who is based in Johannesburg, says.

'I have endured hate messages'

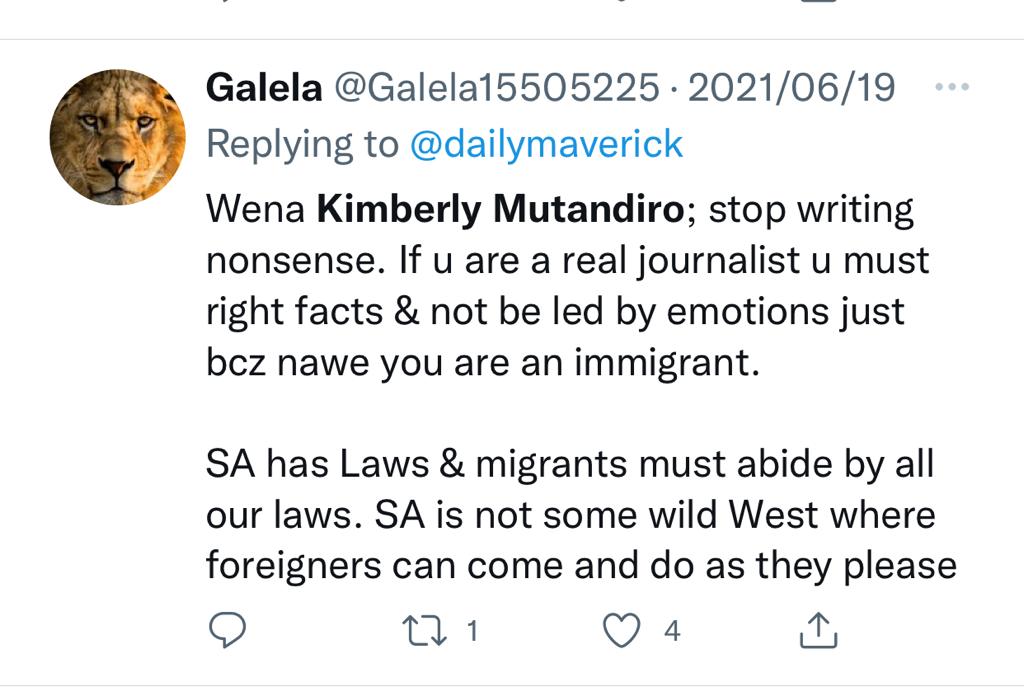

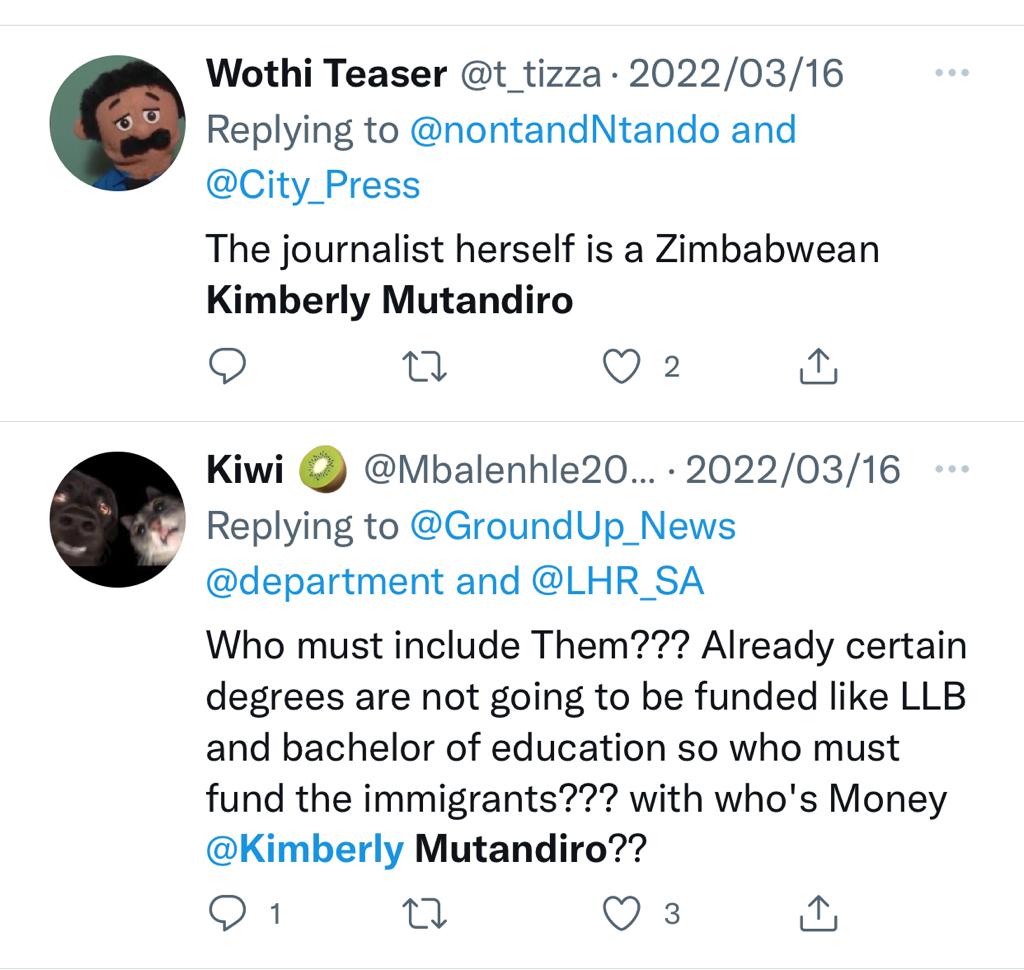

With the rise of anti-migrant vigilante groups, which actively seek to drive out undocumented foreigners, the number of hate messages Mutandiro receives have also escalated. “During the past year with the rise of anti-migrant campaign groups on Twitter, I have endured having hate messages sent to my Twitter account, being told to go and write such in Zimbabwe,” Mutandiro says. “It has been heartbreaking, but I have enjoyed representing the voices of minority migrants who hardly have anyone speaking for them.”

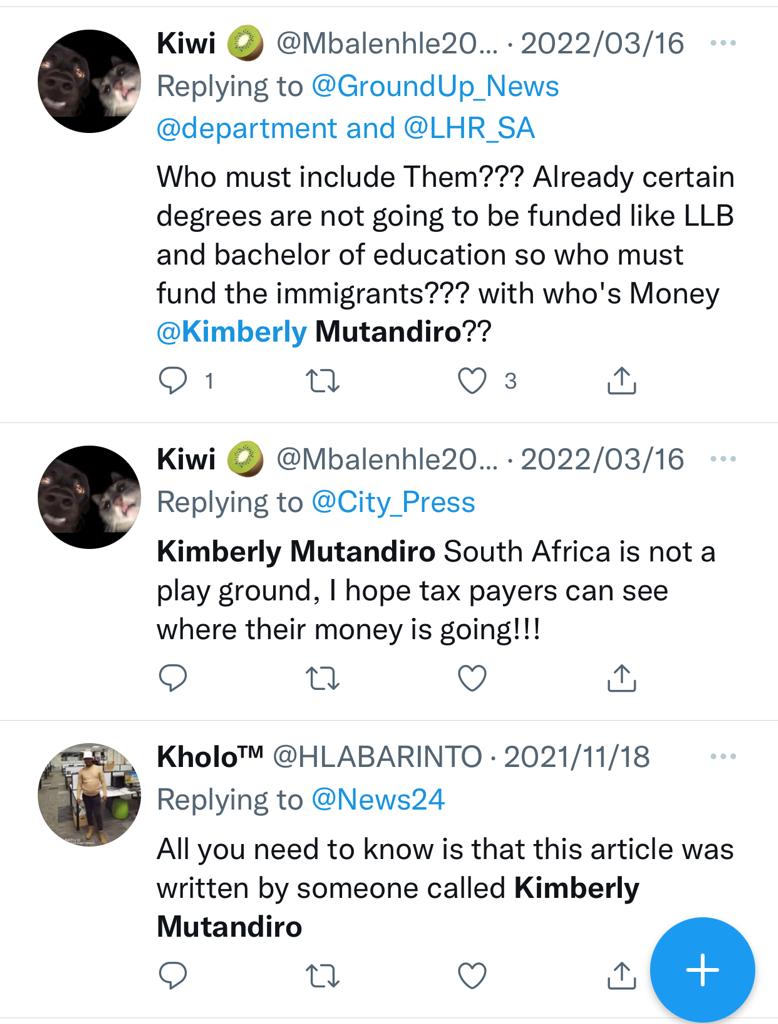

Mutandiro’s article published by GroundUp, where she wrote on how immigrant children were being sidelined from student tertiary financial aid because they are not South Africans - despite often having grown up in the country - triggered a social hate onslaught. The article, later carried by City Press, a mass circulating publication, also resulted in hate messages, calling on her to “go back home”.

“City press hires foreigners in SA to write about the struggle of immigrants in SA. Is that allowed??” wrote “Mongweko” on Twitter.

Another response by “SKHOKHO” added that “First thing is first @KimberlyMutandi journalism is not a scarce skill, you are therefore illegally practicing journalism here in SA. Secondly NSFAS or any bursary scheme owes foreigners nothing. U should be holding zimbabwe accountable not SA! Spreading nonse propaganda here.”

Besides online hate speech, Mutandiro says she was also stalked by anonymous people demanding to know who her sources are after she wrote a story about xenophobic attacks in South Africa.

“At one-point, I was even stalked by someone who prompted me to reveal where I live after publishing a story on a xenophobic incident. The best tactic for me is being vigilant at all times,” she says, adding that, as a journalist, she is bound to protect her sources at all costs. “In most cases, obviously as a journalist, I reserve the right to protect my sources.”

Voice of the marginalised

Although she has not reported the hate incidents, the journalists she works alongside are well aware of them. Despite the seriousness of some of the comments, Mutandiro continues to cover underprivileged communities. “Migrants in South Africa are very marginalised and their plight is underreported. In most instances the mainline media drive the narrative of the status quo based on the assumption that all migrants in South Africa are undocumented,” she tells Al Jazeera Journalism Review.

As a migrant herself, writing on issues affecting fellow foreigners is personal. “Migrants' voices on some of the issues are silenced. My working on migrant stories is a way of breaking the silence. In particular, the issue of xenophobia is heartbreaking with many migrants losing lives to some of its brutal effects,” she says. “Writing about migrants for me is a part of advocacy journalism, advocating for justice to prevail in migrant communities.”

Ironically, when Mutandiro reports on issues facing local South African communities generally - often with equal levels of criticism aimed at the authorities - she has not faced any backlash. It is only when she delves into migrant issues that she comes up against abuse. “Being an immigrant myself, I am often accused of being biased towards migrants, even though I mostly report on local issues.”

'Migrants are a soft target'

Across the country, Bernard Chiguvare, 59, a migrant freelance journalist from Zimbabwe, based in the Limpopo province, near the border with his home country, faces the same predicament.

For the past seven years, his reporting has focused on vulnerable groups in South Africa, including migrants. Chiguvare is a beneficiary of the Zimbabwe Exemption Permits (ZEP) issued in 2009, allowing migrants to work in the country legally.

“I have covered incidents where migrants living in informal settlements are always a soft target. From my experience, when the locals feel the government is failing to provide basic services to them, then they turn their anger to foreign nationals,” says Chiguvare.

In the line of duty, his numerous encounters reveal that migrants like him are always vulnerable but police only respond when the situation has escalated dangerously. “In most cases police do not quickly respond to the calls of the migrants whenever they are in danger. It is only when shops or houses are burnt that police intervene. During such times, migrants often flee their places of residence and seek shelter in quiet places,” Chiguvare says.

Defending ‘lesser humans’

Usually, he says, the intervention of local community members helps to restore calm. “The migrants will only come back after the situation has calmed and maybe after being assured of their safety by community leaders in their respective areas. In most cases during such times migrants are fed by well-wishers as they will not be safe going out to work.”

As the anti-migrant attacks swell, it seems like they are “lesser humans”, Chiguvare says. “As a migrant, I noted that one has to accept and forgo some of your fundamental human rights. Though crimes are committed by anyone regardless of nationality, it is now a common concern that where crimes are committed, the public’s first suspect is a foreigner. But after police investigations this may be proved wrong.”

Aside from covering migrant issues, Chiguvare has also been confronted by protesters while reporting on general community news as well. “When I was covering one story, I was nearly attacked by protestors. When I arrived at the scene it resembled a battle field. I started shooting photos, but several protestors turned on me. I explained that I was a journalist and produced my press card but it was torn up. Fortunately, I had another press card.”

Despite the obvious risks, Chiguvare always maintains ethical reporting and seeks the views of police, relevant authorities or community leaders, to avoid unfounded claims or allegations and thus avoid a backlash as much as possible.

“Ethical rules of reporting should dictate one's reporting. It will be good practice to understand migrants affected by violence but one should avoid ‘hyper’ reports. This has to be checked,” he says.

To guard against attacks, migrants must always ensure they are respecting the laws of the country, says Chiguvare. “Anyone who breaks the law should face the full might of the law. So any cases committed by migrants should be reported in a manner that will show other migrants that they should be law-abiding.”

Another possible solution, Chiguvare says, is for journalists like him to have a balanced view and regularly interact with the community. “Usually locals hold community meetings. It's our work to cover such meetings and capture what locals and migrants agree upon. In most cases, community meetings are attended by locals but very few migrants and the voice of the migrant is missing. Such meetings amplify migrants’ activities in the areas they leave. As journalists we need to find the voices of migrants wherever we are.”

An uncertain future

After years reporting on migrants, Mutandiro believes that her writing is helping change the perception of migrants. “As journalists, we do offer solutions to the violence. By giving a voice to migrants, yes, I think we have done our best to highlight the issue. Although l feel there is a lot more that needs to be done in terms of finding solutions,” she says.

But sadly, she feels let down, which leaves migrants vulnerable. “The South African government needs to play an active role in finding ways of stopping the violence. However, social inequalities in the country leave a lot to be desired, whether or not the government will be able to resolve such inequalities is another issue. But as long as poverty and unemployment continue, immigrants will always find themselves as victims.”

As the wave of anti-migrant violence continues, the future of both Mutandiro and Chiguvare remains uncertain. “The environment in South Africa is obviously uncertain for most migrants working in South Africa particularly those on the ZEP permits,” says Mutandiro. “I was not on ZEP, but I am on a student permit that allows me to study while working part time. Groups such as Put South Africans First have been advocating to put an end to migrant unskilled labour. Journalism is not on the critical skills list which automatically puts us in a difficult position,” she adds.

Chiguvare, a holder of the ZEP, however, faces an uncertain future, together with other 178,000 beneficiaries from Zimbabwe, after the South African government cancelled them last year. “I am also a holder of the ZEP which expired last year in December. The South African government extended a grace period of up to December 2022. Most of the holders of the ZEP do not qualify for any other visas available. I wish the South African government would review its decision not to extend the permits.”