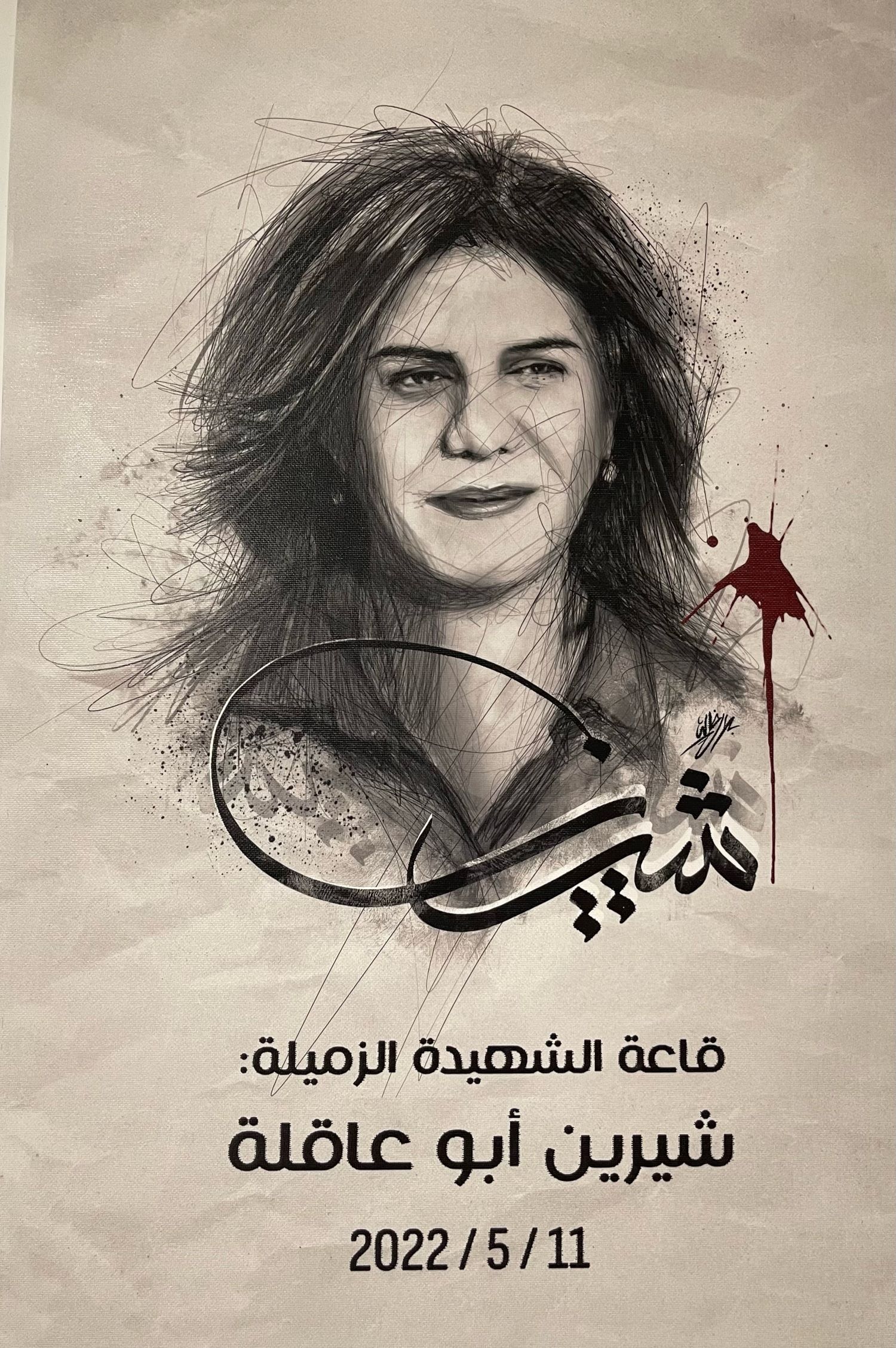

Al Jazeera English’s Senior Correspondent recalls the last time she saw Shireen Abu Akleh and what it has been like to cover the investigations into her killing by Israeli forces

I am haunted by the look in Shireen’s eyes the last time I saw her. Every day of my recent assignment covering the beat she embodied, that final snapshot of her was lodged in my head like a screensaver. She and I were both veteran correspondents, close in age and Arab American women. Though we met only a few times, those common links created a kind of membership to an exclusive club. So, when I saw Shireen a month before she was killed while reporting on an Israeli raid in the Jenin Refugee Camp, I recognised the look in her eyes and the weariness that washed over her face.

It was mid April and we were standing on a hilltop overlooking the refugee camp where she would be shot dead in the back of the neck in that palm sized space between her helmet and the collar of her blue PRESS flak jacket on May 11. We were reporting on the military raids in the occupied West Bank following a wave of violence that killed 13 civilians in Israel between March and April, according to the Israel Security Agency. A few of the attackers came from Jenin which is a bastion of resistance to the Israeli occupation and the military was conducting almost daily, sometimes deadly, raids across the West Bank. The Israeli government vowed to restore calm and security. The Palestinian Authority & human rights groups accused Israel of collective punishment.

We stood side by side doing live shots for most of the day. During a lull, I walked over to her crew’s SUV where she was sitting in the passenger seat. She was somewhere far away from Jenin, until I began talking. When she looked up, I immediately felt like I was yet another intrusion. I’d obliterated however many minutes of peace she’d been trying to hoard. Shireen was ground down. She had been working around the clock. There was no end in sight to this latest cycle of violence and the punishing expectations of covering it as a Palestinian correspondent for a 24-hour news network. I mostly spoke. I told her to take care of herself and commiserated about the demands of the desk I knew would come like a tidal wave.

I won’t ever know exactly what was on Shireen’s mind in the weeks before her killing. However, when you’ve logged more than 25 years in the field as correspondents as we both had, navigated a lifetime of newsroom politics that rival any Fortune 500 company and tried to carve out an unconventional life for yourself, you arrive at the junction of middle age, what’s next and is there more than this peripatetic journalist’s existence? It’s one of life’s countless injustices that Shireen was robbed of the opportunity to navigate her way forward from this crossroads.

A month after that encounter as I watched the sun rise over Lake Michigan from my home in Chicago, I began my usual wake-up scrolling of breaking news alerts from overnight and missed texts. Among them the alert that an Al Jazeera correspondent had been killed in the West Bank followed by WhatsApp messages from my colleague and friend Stefanie Dekker.

When I found out it was Shireen, I knew this would devastate her colleagues who became her family. My mind immediately rewound several years ago to our first meeting inside the Ramallah bureau. Shireen walked downstairs to the Al Jazeera English office and the producer introduced her as a “legend” and the “best correspondent at Al Jazeera Arabic”. These were not platitudes tailored for a guest. I felt that admiration and love for Shireen. She exuded a gentle dignity. I would later observe how even in the uber-competitive camp of correspondents often with outsized egos and bombastic personalities, she seemed to hover in a more rarefied realm. When I returned to the West Bank in the summer I saw how her absence had shattered her Al Jazeera family.

The news of Shireen's death was like the knock-out punch in a boxing ring

No one was surprised. Yet, the news was like the knock-out punch in a boxing ring. Except her colleagues still had to get up and get the story on the air. On September 5, the pursuit of justice and any hope of accountability within Israel for Shireen’s killing came to an end.

As widely expected, the Israeli military announced that there would be no criminal investigation into the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh. A senior military official said there was a high probability that a soldier accidentally killed her. However, multiple investigations concluded there was no violation of policy. In short, the senior military official said her death was a devastating loss of life.

The official repeatedly told international journalists during a briefing that on May 11, the Jenin Refugee Camp had become a battlefield and there was a prolonged gun battle with armed Palestinians. He said it was impossible to rule out the possibility that Shireen was killed in the crossfire. Yet, he did not explain why video taken the moments before Shireen was killed appear to show a calm scene with no sound of gunshots. He did not respond directly when asked why witnesses say even as Shireen lay on the ground people who tried to assist her were being shot at. The Israeli Military concluded with “100 percent certainty” that its soldiers did not target Shireen or any journalists and it said it cherishes freedom of the press.

The families of the almost 50 Palestinian journalists who have been killed during the Israeli occupation that began in 1967, might find that difficult to believe.

About two weeks before Shireen was killed, the International Federation of Journalists, the Palestinian Press Syndicate and human rights attorneys submitted a complaint to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague alleging the Israeli military is systematically targeting Palestinian journalists. The complaint says Israel’s failure to investigate the killings of journalists is tantamount to a war crime.

The day the Israeli military investigation into Shireen’s killing was made public, it resurrected the trauma of my colleagues. Despite their professionalism, their pain, anger and helplessness were evident. I worried about my crew especially as we edited our story. It contained images of Shireen after she was killed. Each time the clip appeared on the laptop I looked at the photographer and producer and saw their torment.

For most, Shireen was an acclaimed journalist killed in the line of duty, bravely chronicling the occupation of the Palestinians. But this was her story, her life. It is the fraught existence of the Palestinians. My colleagues wondered aloud if they were doing enough to keep the pressure on the international community to amplify her family’s message that “our dear Shireen can not be swept aside.” To be a Palestinian living under Occupation brings a kind of fatalism. Shireen’s colleagues know the long odds of justice. Nevertheless, Al Jazeera’s legal team submitted a case and Shireen’s family submitted a complaint to the ICC.

As a roving senior international correspondent, I am a guest when I work in our Gaza, West Bank and Jerusalem bureaus. I am hyper-conscious of the fact that Palestinian journalists are living and working in a dangerous environment where their very existence is threatened. I suspect the passion to document the real time history of their people is an antidote to stave off hopelessness. It’s impossible to forget that my colleagues at Al Jazeera also live with the possibility no longer abstract, that one day they could get a call to cover a story and it will be their final assignment. Even in death, Shireen “the voice of Palestine” is reminding the world of the almost 50 journalists who have been killed on assignment in their homeland.