It's been eight years of “hell” at the maximum-security Kondengui Central Prison in Cameroon’s capital, Yaounde, for journalist-cum activist, Mancho Bibixy Tse, yet the 39-year-old rejects any offers of conditional release that would force him to renounce his right to freedom of expression. Mancho was charged with terrorism, secession, rebellion, inciting civil war, and spreading false information through social media by the Yaounde Military Court in May 2017 and slammed a 15-year prison sentence.

My family, my journalistic work, and my people are all shackled. We are a people subjugated and dominated by the Cameroonian government. My ultimate desire is the complete liberation of my people.

Mancho Bibixy Tse's Story

Six months earlier, Mancho had instigated what later became known as the “Coffin Revolution” when he mounted a casket at a crowded roundabout in Bamenda, the capital of Cameroon’s English-speaking North West region, to denounce the social and economic injustice of his Anglophone community. His act of civil disobedience was a defiant manifestation of pent-up anger over the appointment of French-speaking teachers and magistrates in Anglophone schools and courts. On July 22, 2019, Mancho led another protest against inhumane conditions at the prison. This earned him an additional two-year sentence. “I was kept handcuffed for 15 days. I didn't eat for the first two days and ate once a day for the rest of the days,” he tells AJR.

Prior to his arrest, Mancho, who holds a BA in journalism, was working with Abakwa FM radio station, Cameroon National Television (CNTV) in Bamenda, as well as Feedback Magazine. He says he embraced journalism as a profession and activism out of passion and claims to know how to separate the two.

“In journalism, I work independently and adhere to its rules. In activism, I set the rules and choose my colleagues, whom I regard as comrades or combatants. Sometimes, it involves heeding the people's cries,” Mancho explains. “Choosing to be a freedom fighter means being ready for imprisonment, exile, or even death,” he continues. “My family, my journalistic work, and my people are all shackled. We are a people subjugated and dominated by the Cameroonian government. My ultimate desire is the complete liberation of my people.” Facing an additional five-year sentence for unpaid court fines, Mancho remains defiant. “I refuse to pay,” he declares, dismissing the charges against him as baseless. “I find myself detained in a land that is foreign to me, with an unfamiliar language and culture.”

The Conflict in Cameroon and its Roots from the Colonial Era

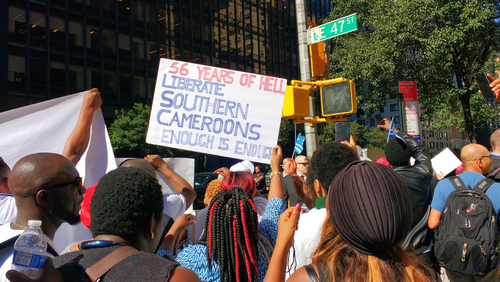

Violence has torn through Cameroon's two English-speaking North West and South West regions since 2016 after the government imposed French-speaking teachers and lawyers on Anglophone schools and courts. At least 6,000 people have so far been killed, and nearly a million others have been displaced. The war pits Cameroon's soldiers and Anglophone militants seeking a breakaway country, which they term Ambazonia. The war stems from Cameroon’s past, which was first colonised by Germany (1884–1916) and later split between France and Britain. French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, joined by English-speaking Cameroonians through a federation a year later, after a vote in a UN-organised plebiscite. The French-speaking section constitutes about 80 percent, while the English-speaking section constitutes about 20 percent, both in terms of territory and population. A controversial referendum in 1972 abrogated the country’s federal structure, which guaranteed the rights of the minority Anglophone section.

Like many other journalists who have worked in Cameroon’s hostile environment, my body, soul, and spirit bear too many scars from their persecution. However, I am proud I endured that abuse and will always wear it as a badge of honour,

Exiled Voices: The Intersection of Journalism and Activism in Cameroon's Turmoil

The conflict in Cameroon has ignited debates on the blurring lines between journalism and activism. Some observers have expressed fear that the blurring lines could undermine the integrity of the journalism profession while also making coverage of conflict more dangerous. Yet others believe these two terms complement each other more than they oppose each other. The major thrust of the argument is how possible it may be for a journalist to be an activist for a cause without compromising the core editorial values of journalism. Mancho's story is all too common for many journalists operating in Cameroon's conflict-affected regions. The war has put many journalists-turned-activists in conflict with Cameroonian authorities. Many have ended up fleeing the country.

Christopher Fon Achobang, a Cameroonian social and environmental justice activist and former stringer for local tabloids, now a columnist at Modern Ghana, was compelled to flee Cameroon on August 1, 2021. Settling in Uganda as a refugee after transiting through Nigeria, Cotonou, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea-Conakry, Achobang left his homeland while being pursued for alleged terrorism and support for separation and secession, charges he attributes to his reporting on war crimes and crimes against humanity in Cameroon.

In the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, the negative role of Radio Television Mille Colines in the brutal murdering of Hutus and Tutsis is well documented. These have become playbooks for others to emulate, especially in the ongoing conflict in the North West and South West Regions of Cameroon.

“The charges were based on my pro-Ambazonia stance expressed on Facebook,” the 57-year-old explains to AJR. “I've faced multiple court appearances and pre-trial detentions, accused of falsely claiming the title of human rights defender during my activism.” Achobang firmly believes in the inseparability of journalism and activism, considering them mutually inclusive. “As a journalist, I am inherently an activist,” he asserts. “Without social and environmental issues, there would be nothing for me to report.” Achobang describes himself as comfortable in the dual role of a human rights defender and journalist, focusing on human rights, environmental, and social justice issues—a holistic approach to justice.

Journalism as Activism: Ntumfoyn Boh Herbert's Stand for Integrity

Similarly, Ntumfoyn Boh Herbert, another Cameroonian journalist and human rights and democracy activist, has fallen out with the country's authorities. Now serving as the editor-in-chief of the Africa Freedom Network in the United States, Ntumfoyn views journalism as a form of activism enabled by democracy and human rights. “Like many other journalists who have worked in Cameroon’s hostile environment, my body, soul, and spirit bear too many scars from their persecution. However, I am proud I endured that abuse and will always wear it as a badge of honour,” Ntumfoyn tells AJR. He criticizes the Cameroonian government in Yaounde for its disdain for journalism and activism, especially those supporting democracy and human rights.

Ntumfoyn elaborates on how he navigates potential conflicts between journalism and activism, emphasizing integrity. "For example, when I couldn't ethically endorse the regime's propaganda on state media, I resigned from Cameroon Radio Television (CRTV)," he explains. "Similarly, when I joined Ni John Fru Ndi's presidential campaign in 1991–1992, I stepped down from my roles as a correspondent for the BBC, Africa Numero Un, and Agence France Presse. And during my tenure in communication or public relations with the United Nations and the World Bank, I refrained from practicing journalism."

Ntumfoyn thus views journalism as a form of activism that upholds democracy, human rights, civil liberties, and freedoms. He expresses concern that journalism is increasingly threatened by propaganda, fake news, misinformation, censorship, hostile media legislation, and confusing online billboards. Additionally, he points out the challenges posed by limited funding for local news, reduced revenue from sales and advertisements, and the prevalence of 'yellow journalism', where paid reports are misleadingly presented as news.

The Evolving Role of Journalists in Cameroon's Political Landscape

Dibussi Tande, a Chicago-based Cameroonian political scientist, writer, poet, and digital activist, similarly observes that the convergence of journalism and activism in Cameroon is not a recent development. “They were citizens before being journalists,” Tande explains to AJR. "Given their political awareness and outspoken nature, it's natural for them to engage in, support, and even lead movements for change."

Tande recalls key historical moments when Cameroonian media played an activist role, such as during the pre-independence era and the early 1990s. "Back then, private print media led the charge for political liberalism and the establishment of multiparty politics. Programs like Cameroon Calling significantly contributed to the Anglophone political awakening and the multi-party debate in 1990," he notes. For Tande, the boundary between journalism and activism is exceedingly narrow. He defines an activist as someone who mobilizes the masses for political action. "Even 'development journalism,' which many African states promote, is inherently activist. Its objective is to engage the public in the state's economic development goals. Essentially, journalism at its core is a form of activism," Tande asserts.

This confusion between activism and journalism is problematic, especially for those who are uninformed or uneducated on the subject

Journalism and Activism: ‘Two Opposite Sides of the Spectrum’

Kingsley Lyonga Ngange, Associate Professor of Journalism and Mass Communication and Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Research, Cooperation, and Relations with the Business World at the University of Buea, Cameroon, firmly believes that journalism and activism represent two distinct realms that should always remain separate. Currently a Fulbright African Visiting Scholar at the College of Journalism and Communications, University of Florida, USA, Professor Ngange expresses concern that many activists, often trained in journalism and mass communication, can potentially manipulate the public. "This confusion between activism and journalism is problematic, especially for those who are uninformed or uneducated on the subject," he states.

Professor Ngange, who is working on a book titled “From Newsroom to Classroom,” emphasizes that journalism is a profession dedicated to researching, gathering, processing, and disseminating news and information with strict adherence to principles like objectivity, fairness, balance, and accuracy. “It aims at educating and informing citizens so they can make independent and informed decisions without force,” he explains. In contrast, activism is about strategic actions aimed at social or political change, often involving forceful campaigns to prompt radical actions. "Activists are militants, whereas journalists are professionals," he asserts. He points out the danger when journalists engage in activism, leading to a blurring of roles that can be problematic, especially when they face legal consequences for their activist actions, “they will use the journalism banner to fight for their freedom by saying: ‘journalism is not a crime.’ The two should be separated.”

In a chapter of a book that he co-edited with Professor Emeritus, Tala Kashim, titled “Anglophone Lawyers and Teachers Strikes in Cameroon (2016–2017): A Multidimensional Perspective," Ngange argues that media (especially social media) activism and propaganda contributed more than 70% to the escalation and sustaining of the conflict in Cameroon. “This is not a new phenomenon. People have always used crisis situations to pass across disinformation, misinformation, and even myth information,” he tells AJR.

Neither activism nor journalism on their own made the conflict what it is today. It is the tools and strategies that all the parties used.

“Communication is crucial in crisis situations, and that’s how “propaganda” (which is the dissemination of distorted, partisan, and untrue information) played a central role in the first and second world wars. “In the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, the negative role of Radio Television Mille Colines in the brutal murdering of Hutus and Tutsis is well documented. These have become playbooks for others to emulate, especially in the ongoing conflict in the North West and South West Regions of Cameroon.”

As citizen journalists and activists increasingly utilize media platforms, particularly social media, for agenda setting and framing, Ngange expresses significant concern for the future of journalism. He observes a prevailing public preference for sensationalism, or "yellow journalism," over objective, fact-based reporting, a trend he finds regrettable. "This preference often stems from a desire for the unusual or sensational—akin to the adage that a dog biting a man isn't news, but a man biting a dog is, due to its rarity," Ngange explains. He emphasizes that in light of the rise of activism, sensationalism, and the influence of social media, it's crucial for professionals and communication experts to actively work to safeguard and uphold the integrity of journalism, a field increasingly vulnerable to exploitation by those he describes as quacks and charlatans, drawn to its strategic, influential, and prestigious nature.

The Complex Role of Journalism in Cameroon's Conflict

Tande is not overly concerned about activism overshadowing journalism, believing that “pure journalism will always exist and thrive alongside other types of journalism.” He contends that neither activism nor journalism alone escalated the conflict in Cameroon. “It's the tools and strategies used by all parties involved,” Tande explains. He refers to a study on Cameroonian journalists' coverage of the conflict, noting, “The crisis was mainly reported with a focus on solutions and violence, a departure from conventional crisis reporting that emphasizes problem definition and causal interpretation.” Tande criticizes Cameroonian journalists for avoiding the problem definition approach, which could provoke state backlash, in favor of a safer, solution-based approach, such as advocating for “inclusive dialogue.”

In light of the rise of activism, sensationalism, and the influence of social media, it's crucial for professionals and communication experts to actively work to safeguard and uphold the integrity of journalism, a field increasingly vulnerable to exploitation

Echoing this sentiment, Achobang believes Cameroonian journalists have neglected their potential as agents of social change. “They've become part of Cameroon's social problems,” he argues. “Journalists should be crusaders for change, actively engaging and not remaining neutral. In addressing societal issues, they inherently become activists.”

Ntumfoyn also critiques the coverage of the current conflict by Cameroonian journalists, particularly those in state-owned and pro-regime media. He compares their role to that of Radio Mille Collines during the Rwanda Genocide, accusing them of justifying heinous crimes. “It's disheartening to see journalists and supposed activists failing to fully embrace their responsibilities in such critical times,” Ntumfoyn laments.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera Journalism Review’s editorial stance