What it’s like to host a radio show in the Dadaab refugee camp, situated in one of the world’s most overlooked regions, during a global pandemic.

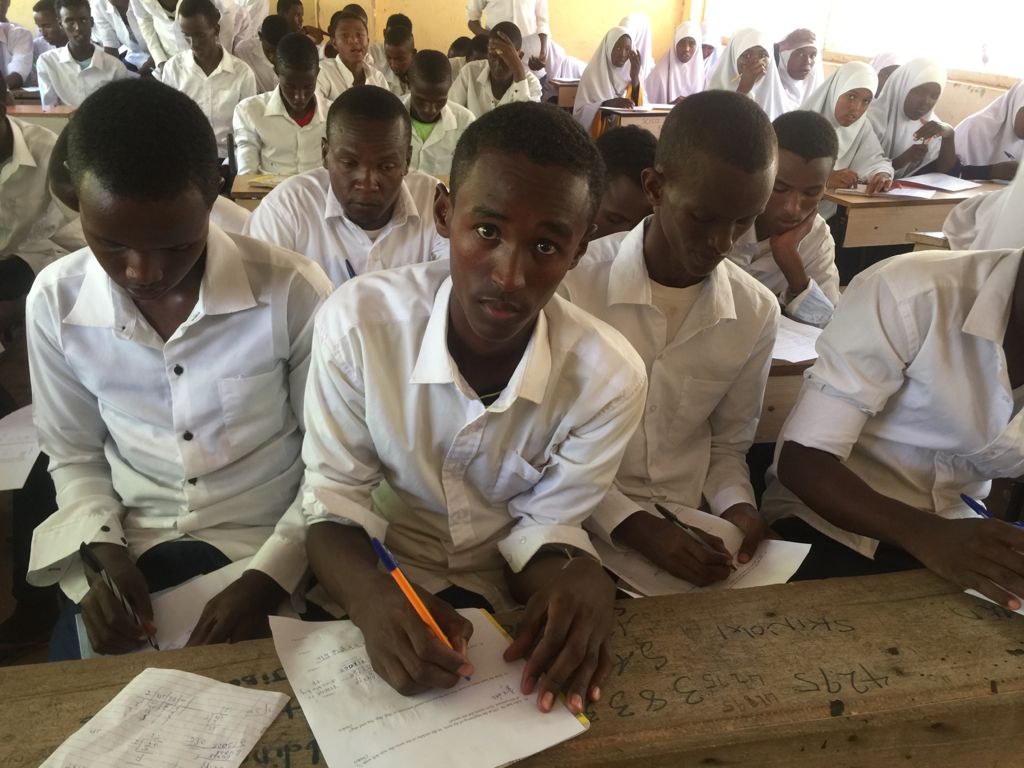

Since early 2020 and right through the months that the coronavirus pandemic was at its height, I have been running a radio show in the Dadaab refugee camp in north-eastern Kenya. Dadaab is one of the biggest camps in the world, housing around 220,000 refugees from different countries, although the majority come from Somalia. I, myself, first came to Dadaab 30 years ago from Somalia at the age of just three, and I was raised and educated here.

Grassroots radio shows such as mine have been providing an essential service to marginalised communities during the global pandemic. According to the United Nations, there has been a huge rise in the numbers of people tuning in to radio programmes over the past 18 months in search of information and reassurance about COVID-19.

This is particularly the case in areas of the world like in the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya where many people are illiterate and do not have access to television or smartphones - but do tend to have a radio.

Providing an essential service

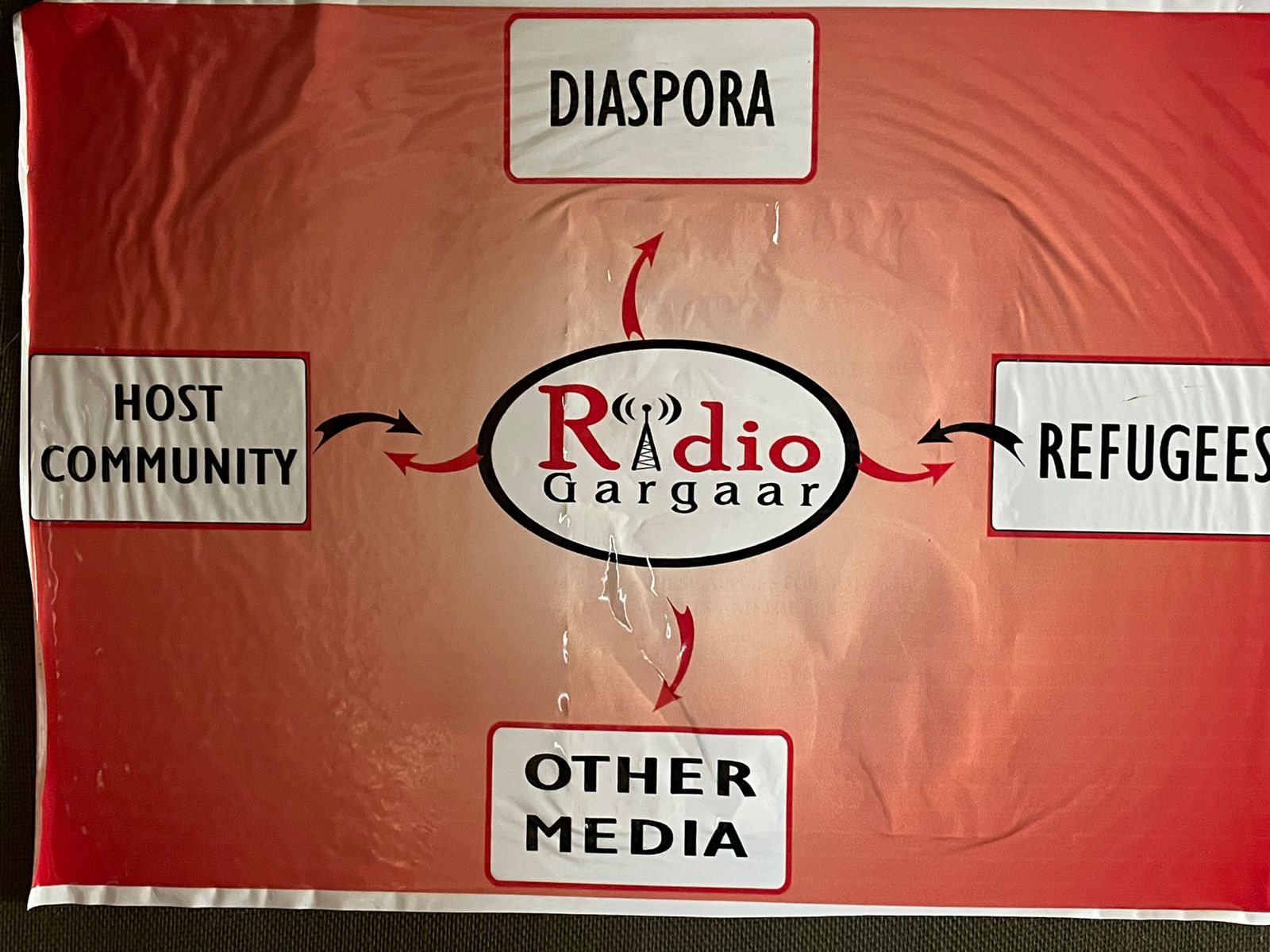

Radio Gargaar (“Gargaar” means “assistance” in Somali) is a community-based radio station based inside the Dadaab camp. It is the primary medium through which members of the community - and those living in the larger community in Garissa County, north-eastern Kenya - stay informed about public health issues. We broadcast primarily in Somali, but also in Oromo, Swahili and English.

At the start of the pandemic, I began hosting a 20-minute daily morning show called “Our Health” at 10am, highlighting challenges within the community, providing information and helping to find solutions for day-to-day health problems in the camp. I also provide the community with the latest news updates related to the coronavirus from government agencies and international NGOs. We started the show specifically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but we cover all health issues. In 2020, we received an innovation award from UNHCR for our work as part of the Refugee Youth Education Hub.

Last year, I was also awarded a grant from the Internews Information Saves Lives fund, which I am using to expand my show from 20 minutes to an hour each day. I also plan to add radio plays and entertainment for children.

We are able to give refugees a voice and a sense of community in a camp with many nationalities who have essentially been warehoused here

At this camp, refugee women come every weekday to seek services such as health care, psychological support, legal aid and support for integration into the community here. They also come to register their new-born babies. The radio show places a particular emphasis on enlightening listeners about social-distancing, washing hands and the importance of wearing masks at all times. We also highlight as much as possible the dangers and risks of the coronavirus to the population.

There are a lot of health concerns in the camp because of the lack of medical facilities and overcrowding due to the high-density population living here, which means the larger population is at greater risk during a pandemic. So, after we have run through all the latest coronavirus updates, we invite callers to ask questions, and we provide clarification about the latest rumours - of which there have been many.

‘They thought the vaccine would cause infertility’

Most people call in for information about public health issues such as the lack of water and sanitisers for handwashing, child marriage, youth empowerment and family planning.

We are able to clarify issues that may be causing confusion. For instance, one man called in to the show to complain that his wife was taking contraceptive pills but they had not worked and she was pregnant. He wanted to know if he should also have been taking the pills.

We told him where he should go for proper medical advice and attention and - from the following calls from listeners - we discovered that many were buying drugs which had either expired or were fake versions of the original because they were cheaper and readily available from traditional healers in the community.

Correcting misinformation is a key purpose of the radio programme. There were a lot of rumors and misinformation flying around about the pandemic early last year, for example. Some of the locals were saying it was a virus that only affected other races, while others who are devout Muslims believed the coronavirus would not affect people from their religion. Yet more locals were claiming the vaccine was a “depopulation tool” which would cause infertility and death. It is our role to debunk all of these myths.

We understand that people here do not always want to follow NGO advice, especially when it appears to go against their cultural beliefs and traditions

There was a marked change in attitude among this community after I reported the death of the popular Somali musician, Mohamud Ismail Hussein - commonly known as Hudeydi - from the coronavirus in April last year.

Another time, a listener called in and claimed he could cure himself of COVID-19 by using traditional herbs. He was adamant about this so, to keep his trust, we advised him to take the vaccine but also to continue with his herbal concoctions.

Being in a Muslim community, we have to respect the culture and traditions of people here. Our advice is geared towards finding community-centered solutions because we understand that people here do not always want to follow NGO advice, especially when it appears to go against their cultural beliefs and traditions.

Giving a voice to the voiceless

I chose to work as a radio journalist because nearly everyone has got a radio. Most people at the camp are illiterate but almost every house has a radio. After growing up in Dadaab and going to college in Nairobi, I started working as a fixer and public information officer for NGOs and media outlets.

I believed it was important to try to give a voice to the voiceless, particularly as I speak their language and I myself was raised in the camp.

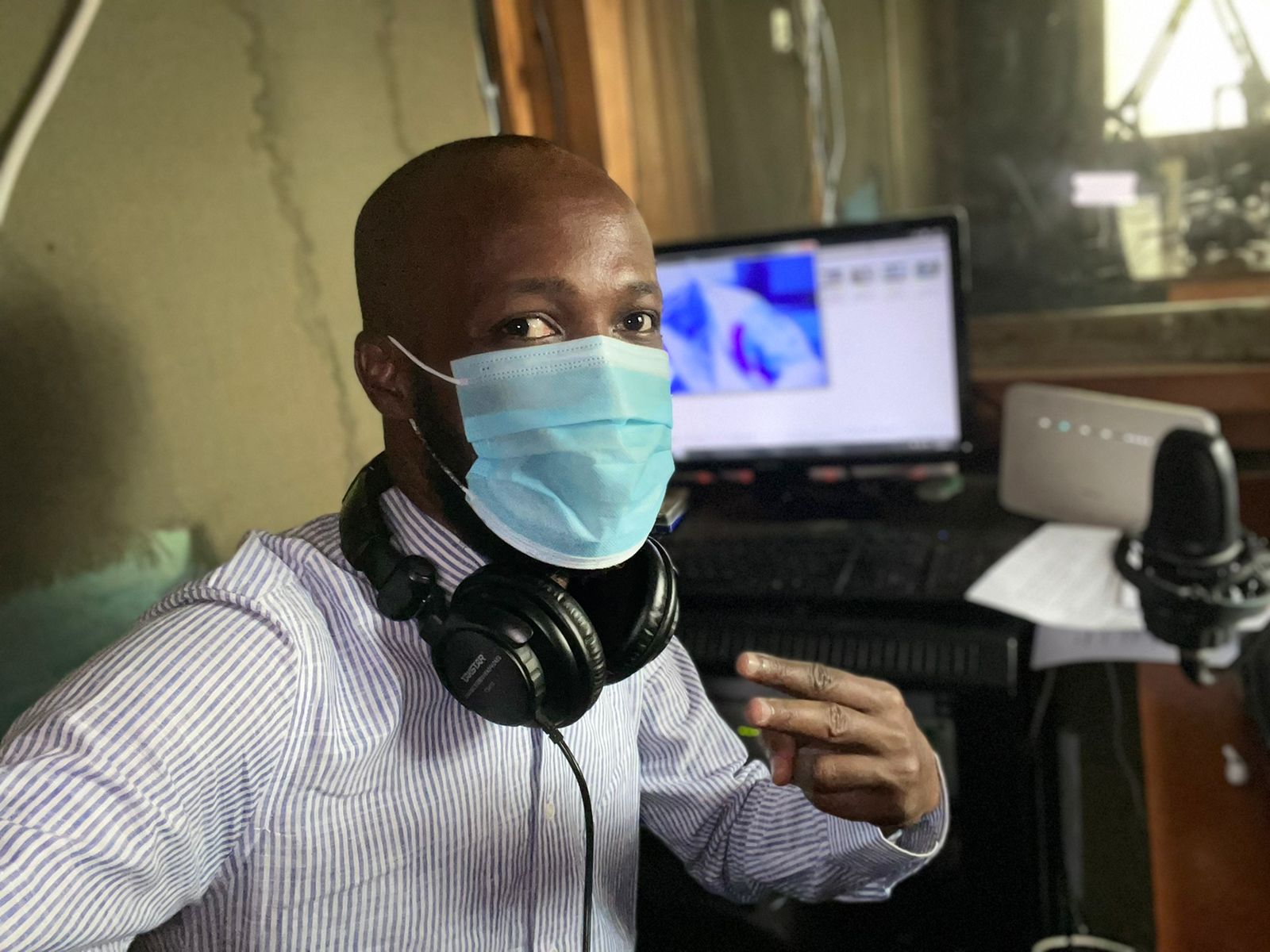

For a while during the pandemic, I moved back to Dadaab from my home in Nairobi to run the radio show. At the moment, I make long trips to Dadaab from Nairobi but when I can’t get there, I can participate in the show using my smartphone, thanks to social media and the internet.

Despite the challenges in raising funding, our radio show is making a difference.

I am always delighted when interacting online with young people who sometimes direct-message me their problems if they don’t want to share publicly, and I am always glad to help.

Through this radio station, we are able to give refugees a voice and a sense of community in a camp with more than 10 nationalities from war-torn African nations who have essentially been warehoused here. The aim is to inspire them to take their destiny into their own hands by telling their own stories.

I am always engaging with them and the vibe here is on another level. From my experience, young people here in particular yearn for better opportunities in life. So, we try to connect young people from different parts of the world through networking. We are continuously building our network of people around our broadcasts.

I have found that the show works as a sort of therapy for many adolescents and helps to keep them away from dangers such as drugs or grooming by al-Shabaab groups.

Radio Gargaar is a case study for international agencies on how to ‘do aid’ effectively

My show builds trust and resilience between the different communities that make up the larger community in and around Dadaab. People know me here. I speak the local languages and I am working to keep my people out of danger from the virus.

What the pandemic has taught us is how we as a community can change our lives through our voices. This is a case study for international agencies on how to do aid effectively. The international community should focus on gearing up funding for community-led projects rather than just importing their own.

With my radio show and the network of people we have built up around it, there is a conversation going on with donors. We are dreaming at least, that someone will hear us.