What does it mean to be a constructive journalist? And how does that translate to photojournalism?

Learning about the concept of ‘constructive journalism’ reminds me of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story”. Constructive journalism seeks to go beyond the "single story", which is one that solely focuses on the "problems", in order to explore the possible solutions as well.

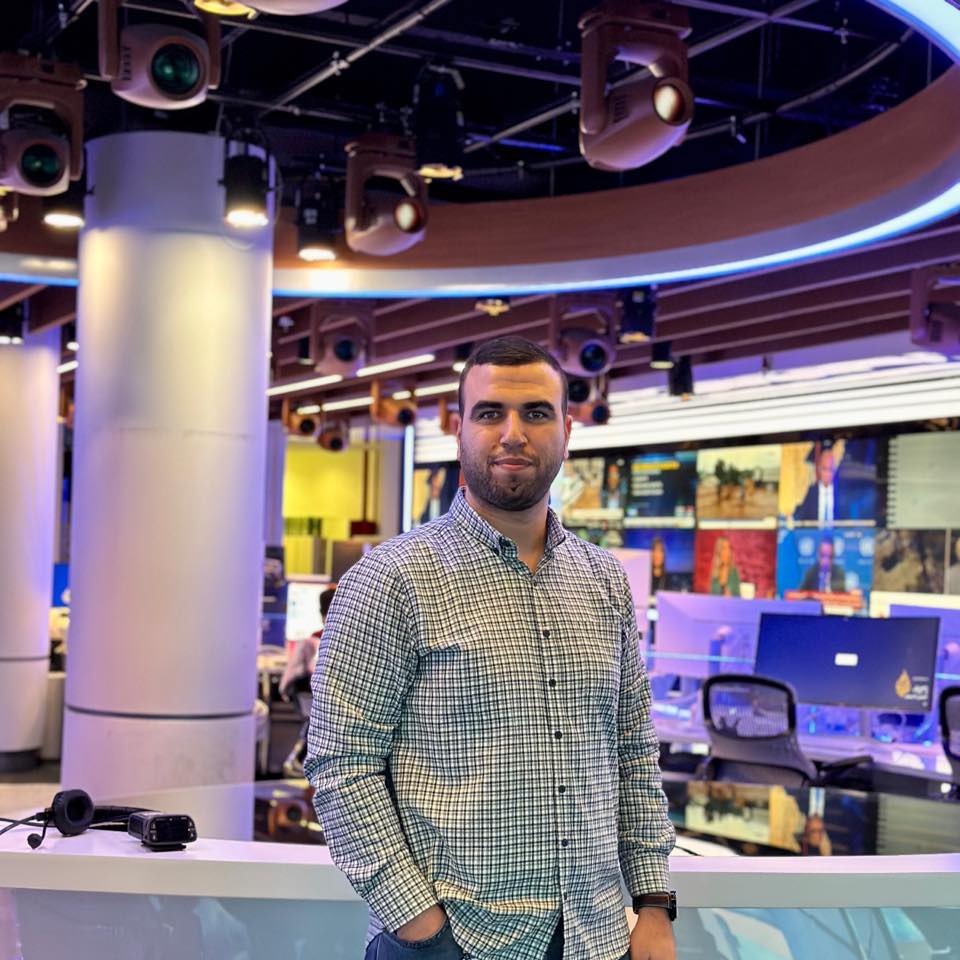

I recently completed a four-month fellowship programme on constructive journalism with the Deutsche Welle Akademie.

They had selected 15 journalists from across the African continent and, over several sessions with world-leading journalists, we dived together into the term ‘constructive journalism’, the style, the ethics and what it means for the future of the media industry.

What Does Constructive Journalism Mean?

Scientists have shown a connection between “doom scrolling” and mental health, and it doesn’t look good. Once upon a time, the screaming headlines of bad news might have attracted our audiences but not anymore. There are so many terrible things happening in the world already, and the audience gets it; they feel it. How does a virus so small for instance, lock the whole world away in fear?

It is time for the media industry to find a new balance.

This is where constructive journalism comes in: what is the alternative to all the ‘problems’ we are bombarded with every day? Sometimes, it is hidden in solutions which may already exist or just by your reportage providing insights into possible future alternatives.

This is what I have learned as a photojournalist.

Lesson 1: Your 'Lead Image' Does Not have to Bleed to Make Your Story Lead

How do we move on from our obsession with catastrophes, disasters, and problems in our reporting?

First, we need a mindset change, personally and collectively. I have been asking myself: what next after your work has shone a light on the problem without providing possible solutions? What has all the ‘bleeding reportage’ led us to as an industry? Or as a people?

There are ways to capture a problem without robbing your subjects of their humanity. As photojournalists, we need to find that way

And this is not just about journalists alone. Media producers, media owners and everyone involved in the entire chain of news production—we all have a role to play. The trick that attracted audiences in the past may not be working anymore. If the game has changed, why are the game players refusing to change?

For constructive journalism to take wings, everyone in the media value chain must be willing to change their mindsets in their approach to news. Yes, it is cloudy out there—our audience see it, they feel it—but do they want to be reminded every time that it is all cloudy and all dangerous? They know it already.

They also know something else: that every cloud has a silver lining. But will we be courageous enough to find and show that silver lining? This also means that I need to have the tenacity to find those few media houses that will be courageous enough to publish the silver lining.

Using Photography to Help Bring Vaccines to the Disabled

As a photojournalist, it is important for me to always try to find the glee in the gloom, the delight in the doom. Sometimes, it is even in the framing of the pictures.

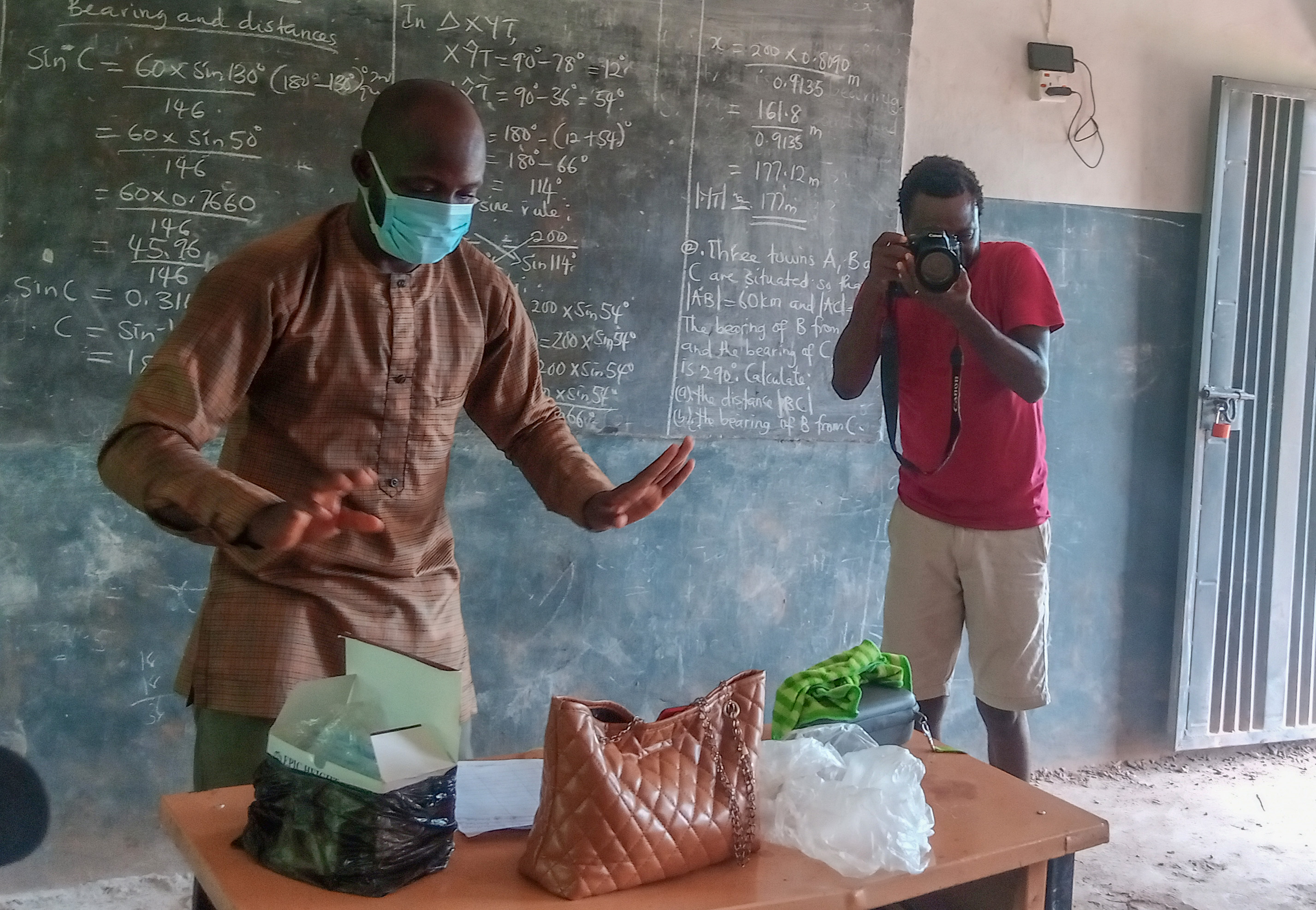

For this particular fellowship, I captured the story of a man who was trying to improve the accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines for Persons with Disabilities (PwDs).

This problem is not new: people with disabilities have always faced challenges accessing healthcare in Nigeria, and the COVID-19 vaccine has been no exception. The solution to this particular issue that polio survivor Raheem Yusuf came up with was by no means a magic wand: the accessibility challenges in the country have not disappeared. However, through his video campaign and vaccination drive, many PwDs have managed to get vaccinated. His story shows us some possible alternatives.

Lesson 2: Constructive Journalism Takes Time and Courage

I have found that photography poses its own set of challenges when it comes to taking a constructive approach to journalism.

Unlike the writer or the video journalist, who can easily flow from ‘the challenge—the issue—to the solution’ in a linear manner, it is tougher to achieve this with photos. Also, pictures are open to interpretation by the viewer. While what they see is out there, how they see it is a different matter entirely.

My experience during the training made me rethink the old saying, "A picture is worth a thousand words.”. Framing is critical. With every shot, I need to ask myself: What are the words this picture conveys? What are the stories embedded in the words? And how can I be “constructive” through the narrative of the pictures?

If you can capture “problems” with a picture, why can’t you capture feasible solutions to the same problems? Constructive journalism takes a cursory look at what we can do about what has happened and how the issue might be better addressed.

So, how do you take images that lead to solutions?

Research is key. Almost every story has been reported before. What is the angle that has not yet been covered?

As a photojournalist, it is important for me to always try to find the glee in the gloom, the delight in the doom

Study the reports; look at the images used in telling the story and how they are captured. And then ask yourself: What is the solution angle to this story, especially in your own immediate location? What new angles can be used to tell old stories? How can the environment of the picture make the story more constructive?

Research also involves having a better understanding of your subjects and where you are photographing them. This not only prepares you for your work, but it also helps you address any personal biases you might have had about the story.

The truth is that "problem-focused" reporting needs to be confronted lest it creep into my shots.

An open-minded call or visit to the people, groups and places whose stories you intend to write about will help to put whatever notion we initially have of them into clearer perspective.

Have a general conversation about your proposed project with those people, listen to them intently, ask questions where necessary and be observant of the environment.

This may also be a good time to start noting the shots you think will fit into telling your story more appropriately. Before leaving, agree on a specific date that is comfortable for them for the actual work to begin. Revisit everything you have written down once you are back home; it may help you decipher more constructive angles.

Sometimes, if you are unable to map out a constructive approach, talk it through with a friend or colleague. Your solution may be in the hands of a friend or mentor.

Sometimes, you need to talk to contemporaries. I call friends who are also photojournalists. Once you present your findings and how you intend to tell the story, listen to their feedback. They may have ideas that that will help you come up with even better constructive images.

Lesson 3: You, the Photojournalist, Are Not an Island

Research provides an avenue for collaboration; the missing piece in your ‘constructive puzzle’ may be in someone else’s hands.

On the day you take your pictures for your report, you cannot talk about the solution without engaging with the problem.

Make your subjects comfortable. Upon arrival at the location, do not immediately bring out your camera and start clicking. Make your subjects feel at home. Talk generally about items of interest; create a comfortable and relaxed environment. You would not want to take an image of an uncomfortable subject. You, as the photographer, also need to feel at home in the environment. This happens only when your subject is too.

If you can capture ‘problems’ with a picture, why can’t you capture feasible solutions to the same problems?

Beyond your specific subject, delve a little deeper into the wider community and environment, and look for other people who may also be active agents in your story.

They may know a great deal about the main issue you are reporting on, and they may be familiar with proposed solutions. Showing their efforts and contributions through your photography of such people may also encourage other people to try out what they have seen or read about once the story is published in their own community too. They may also be part of the story.

While you’re at it, do not forget to be humane. While trying to capture accessibility challenges that PwDs face in the country, it would not be humane for me to photograph them in a humiliating way.

Why would I show another human being helpless on the floor, through no fault of their own, just because I want to illustrate the problem as starkly as I can? There are ways to capture the problem without robbing your subjects of their humanity. As photojournalists, we need to find that way.

Once done, do not hesitate to show your subjects their captured images. Encourage them to voice out their thoughts on the image, mainly to know if they are comfortable with them before they are released. Once they are not comfortable with a particular kind of image with respect to privacy, try other shots—silhouette, close-up, and more.

Lesson 4: When Your Subjects are Comfortable, You Build Trust and Respect

Enough with the problem, it is also important to be deliberate in capturing images that highlight either the subject trying to solve the problem, or which show efforts being applied to solve the problem. So, how do you find that balance?

Nature may have some answers. Nature photography may sometimes come in handy while telling a constructive story. For instance, rather than capture the "obvious stress" on my subject who has just returned from work in the evening wheeling himself home, capturing him against the setting sun, it may be a story of resilience—a more subtle way of telling the story constructively.

After the pictures, then what?

Once you are done with the project and you have carefully selected your final images, you need to provide context through your photo captions. The captions are an important element in constructive journalism; take your time to craft them appropriately. This is key and helps your audience understand your work better.

You don’t want to do an excellent piece of work that will go unseen because of a poorly thought-out title.

On a final note, through doing this work, do not expect to become known as a great constructive photojournalist whose work eliminates decades of knotty representation of marginalised and vulnerable people across the world. However, with constant practice and training and a perception of life’s challenges as solution-embracing, you will contribute to making our world a better place to live in.

I am not deluded that things can change with the magical click of the camera; I know it will take slow, painful steps and a lot of unlearning and relearning: one click, one story at a time.