How a team of journalists spent nearly a year investigating the conviction and 25-year imprisonment of Brandon Jackson and then watched him walk free

On the morning of February 11, 2022, as I watched Brandon Jackson’s Louisiana parole hearing via Zoom, my stomach was in knots. Brandon, who turned 50 in December, had been in prison for more than 25 years.

This was his second time before the parole board. In late 2020, he was denied parole, and his ailing mother Miss Mollie Peoples had a heart attack shortly after.

“It wasn’t the cause but it helped,” Mollie told Al Jazeera. “The heart can only take so much.”

As I watched her face at the bottom of the screen, I worried what would happen if his parole wasn’t granted this time.

As the team behind Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines programme, we spent the better part of 2021 investigating Brandon’s conviction. In partnership with The Lens, a non-profit newsroom based in New Orleans, we explored every aspect of Brandon’s life and his conviction.

Through the process, we learned so much about the criminal justice system in Louisiana. Our reporting had drawn considerable publicity around his case and it felt like there was a wind at his back this time.

The racist roots of non-unanimous jury verdicts

Brandon was convicted by a non-unanimous jury in 1997 of an armed robbery of a restaurant in Bossier City, Louisiana. He denied any involvement in the crime.

At his trial, two of the 12 jurors voted not guilty. They were both Black, however their objections wouldn’t matter.

Louisiana was holding onto a law passed in 1898 during the Jim Crow era that allowed for split juries. The law was designed to mute the voices of Black jurors and convict more Black defendants so they could be eligible as labour for convict leasing programmes.

It was stunning to us that nearly 125 years after the law was originally passed it was still affecting lives today. Although split juries were ruled unconstitutional in 2020, a later ruling said the state would not have to give new trials to people jailed under the law.

One of the biggest challenges that we faced was the lack of transparency and access to prisons in Louisiana. When we were there in the Summer of 2021 it was experiencing a surge of the Delta variant of COVID-19. As a result, the Louisiana Department of Corrections would not allow us to travel to the David Wade Correctional Center where Brandon was being held. This wasn’t the only challenge, prison staff routinely monitored our emails and phone calls with Brandon so we had to be careful about our communications.

In the end, we negotiated to have access to film exteriors of the prison where he was incarcerated and the interview we would have to film over a zoom link. It felt ironic when we arrived at the prison which was located in a very remote part of the state near the border with Arkansas. We had driven hours to get there and Brandon was just on the other side of the fence but we were not allowed to see him.

Our first order of business with investigating his conviction was to comb through the court transcripts and evidence presented at the trial.

Unearthing old evidence

As we dug in, one thing stood out to us immediately. Brandon’s defence lawyer attempted to introduce a VHS tape during the trial, even wheeling out a TV and VCR into the courtroom to get it set up.

But the tape was never played for the jury and nobody was certain what was on it. In a controversial ruling, the judge hadn’t allowed it to be played, citing “attorney-client privilege”. This was farcical as Brandon’s attorney wasn’t representing the witness and there was no agreement in place linking the two defendants. In fact, it was quite the contrary - this witness was going to be the only person claiming Brandon was one of the two robbers that night.

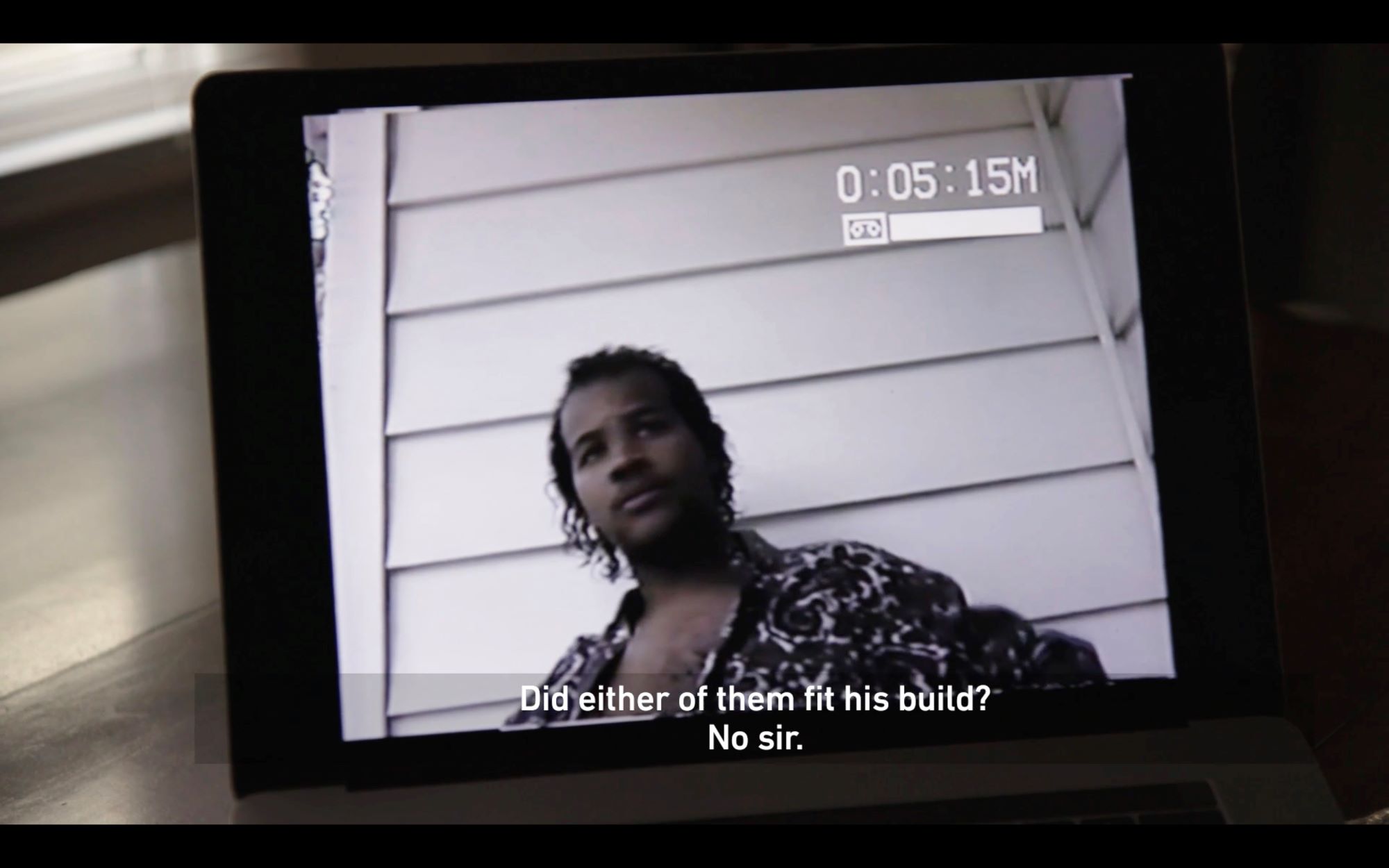

We requested the tape through a public records request. It had been sitting in storage for a quarter of a century. We paid to have the tape digitised so we could see what was on it.

We first played it with our camera rolling as we watched it with Claude-Michael Comeau, Brandon’s current attorney who was overseeing his appeals based on the non-unanimous nature of his conviction.

On the tape, we immediately recognised Joseph Young, the state’s star witness at the trial. In fact, he was the only individual who identified Brandon as one of the armed robbers that night. On the tape, he directly contradicted the testimony he had delivered in court, and it was one of a number of times he was caught changing his story.

That wasn’t the only shady thing surrounding the testimony of Young. He was the one in possession of weapons he claimed were used in the robbery as well as some of the cash. He received probation and, on the stand, even admitted that he was testifying in hopes of receiving a lighter sentence.

We went to the home of Young to see if he would speak with us but he never answered the door when we knocked.

Tracking down the original jurors - with offerings of seafood

Another crucial aspect of the reporting process for us was tracking down the jurors who sat for the trial.

We had a polling slip with the names of the 12 jurors but the trial had happened so long ago that it wasn’t clear if we would be able to easily locate them. In fact, we found obituaries for several of the jurors who had died and it wasn’t looking good for us.

We were able to reach one woman on the phone who had voted against convicting Brandon but all of my subsequent phone calls went to her voicemail.

So we went to Shreveport to try to meet her, but when we knocked on her door, there was nobody home. Things were looking bleak. We returned the next evening, and to my surprise, she opened the door.

“I am not interested in taking part in your project,” she said as she started to close the door on us.

Then out of nowhere Fault Lines correspondent Natasha Del Toro blurted out: “Do you like seafood?”

The door remained open a crack. I explained that if she would just meet us for dinner we could explain more about the project and she would not need to commit to doing an on-camera interview with us.

Later that evening, we broke bread with a round of Bloody Mary’s and the famous fried “shrimp buster” at Herby K’s, a Shreveport institution that has been around since the 1930s.

She later explained her hesitancy to us. She was worried that if her bosses found out that she was speaking out about this conviction, there could be blowback for her at work. “They think a lot like the people on the jury did: ‘He’s a criminal, let’s get him off the street. Let’s lock him up … Or maybe, even, he’s a Black man, let’s lock him up,’” she told us.

When she was younger, she had had an encounter with the Ku Klux Klan in Bossier Parish that she could never shake from her memory. We agreed to protect her identity and blur her name out of the documents if she would give us her account of the trial.

Hers turned out to be one of the most compelling parts of our story. She explained that she tried to speak up in that jury room about the lack of evidence presented at the trial but nobody would listen. Ninety-nine years after the original Jim Crow era law was passed it worked exactly how it was designed: the voice of a dissenting Black juror was ignored. Another Black man was being sent to prison.

Harnessing the power of local journalism

Our project was born in December 2020 when I first began speaking with the editor of The Lens. It is a digital news publication that is based in New Orleans with an excellent reputation for dogged local reporting.

This was the first time that I entered into a partnership like this but it made total sense to me. Here was a dynamic group of journalists with excellent local connections and knowledge about a story that was new to me. We agreed that they would publish print pieces, including a long-form digital story that we would run on the Al Jazeera website.

In turn, we would produce our 25-minute documentary and we could release all of our reporting at the same time.

It was about a week into filming that our team gathered for breakfast at Slim Goodies Diner on Magazine Street in the Garden District of New Orleans. It is a divey diner but they had a big back patio where they allowed us to film phone calls that we were making to sources who we were struggling to track down.

As our team talked through our filming plans, we realised that Brandon’s story was particularly powerful and would likely be the entire focus of our film. We were asking everyone we interviewed about the case so we could use it as the anchor for our story.

Hunting down the District Attorney

Over a “Les Bon Temps Omelet” that was stuffed with crawfish etouffee, we decided that there was really only one person with the power to do something about Brandon’s case. His name was Schuyler Marvin and he was the District Attorney for Bossier Parish.

If we could explain to him about all the evidence we had discovered about Brandon’s conviction maybe he would agree to vacate the case. We called his office and left messages but never heard back from him.

We could abandon our previous filming plan in New Orleans and drive back to the Bossier Parish Court House to try and find him. That would mean waking up at sunrise and driving more than five hours across the state with no guarantee that we would be able to track him down.

The team decided this was an element that we definitely needed and we would make the sacrifice to give it a try. I remember feeling grateful that I am able to work with thoughtful colleagues who are willing to put in the hard work we needed at this crucial juncture.

When we arrived at the courthouse late the next morning we were excited to see a car parked in the parking space reserved for the District Attorney. Our plan was to wait outside in the heat and approach him when he walked out to his car.

However, when a woman walked out and got in the car, we realised he wasn’t there. She told us we could check at his other office in neighbouring Webster Parish. We drove over to a small town called Minden and went into his offices but nobody was there either.

Our last resort was to knock on the door of his home and hope we could find him there. He wasn’t there but we spoke to his daughter and explained that we were trying to reach him.

She said she would call him on our behalf and have him call us. We started the long drive back to New Orleans, I apologised to the team. We had spent a ton of energy trying to track him down and, as it was late in our production schedule, we really only had that one chance to speak to him. My colleagues said not to worry - sometimes it takes weeks to get someone on camera.

But about half an hour later, Natasha’s phone rang in the car. We all looked at each other and sure enough, it was the District Attorney, Schuyler Marvin.

Our cinematographer Singeli Agnew scrambled to turn the microphone on and get the camera rolling. Natasha turned on her speakerphone and we filmed the interview while she was driving. She asked him why he wouldn’t agree to look at Brandon’s case, given all the evidence we had uncovered.

He claimed he knew the racist roots of the law but wasn’t familiar with this particular case. “I’ve only been the DA for 20 years,” he said as if he was new to the job. He promised to take a look at the details and get back to us.

It was more than a month later when he finally sent us a letter saying he was not going to reverse any cases purely based on the non-unanimous nature of the conviction. It appeared that in this conservative corner of the state, there was going to be no way out of prison for Brandon.

‘He has been behind bars for long enough’

That brings us back to his parole hearing on February 11, 2022. Brandon’s fate and that of his mother was in the hands of a three-judge panel. The conversation mostly focused on Brandon’s criminal history and a disciplinary write-up he received in 2019. His record otherwise was impeccable, and he was clearly a good candidate for release.

When the judges began to reveal they were voting to grant him parole I was overwhelmed with emotion. Surprisingly we got word later that day that the warden at David Wade Correctional Center had ordered Brandon to be released the very same day. This is a rarity in Louisiana, sometimes it takes weeks for someone to actually be released. The warden reportedly said: “He has been behind bars for long enough I think, I need him to be out of here by 4pm today.”

Brandon’s mother scrambled a ride out to the prison to meet him as he exited the gates. The Shreveport Times sent a photographer to take pictures of that amazing moment in which they reconnected.

When we started this project I remember thinking about whether it would be possible or not to see Brandon walk free. In our conversations, Brandon and I always said that we hoped the result of our project would be to shed light on this racist practice. We weren’t making a claim of innocence. We were out to prove that the law that convicted him was racist and wrong. Hundreds of people still remain behind bars due to non-unanimous convictions.

We did everything we could to get more publicity for the case. The Shreveport Times and The Lens continued to cover the story after our documentary aired. We did interviews on NPR stations to try and spread the word about these convictions rooted in the Jim Crow era. We felt like the more sunlight the issue had the more the state would have to reckon with its racist past.

A lot of people have asked me since Brandon was released: “Do you think Brandon would have been granted parole if it wasn’t for your story?”

The truth is, we’ll never really know. And in the end, it doesn’t really matter. Brandon was able to walk free again and hold his mom’s hand just as they had always dreamed of doing together.

Watch the Fault Lines episode: