A journalist looks back at the founding of RASSD News Network during the Egyptian revolution, which trained and supported ordinary citizens to become journalists

Egypt has had several presidents since the founding of the Republic after the Second World War. They have varied in style and legacy, but shared one thing: their disdain for accountability and a free press. During the rule of the last-but-one president, Hosni Mubarak, suppression of both political opposition and the media culminated in a popular uprising calling for the fall of the regime. Youth unemployment and police brutality brought to an end three decades of his rule.

In the run up to what became known as the Arab Spring, key moments defined the lead up to the mass protests that toppled the Egyptian president in 2011. It is in this context that this chapter on the youth news network RASSD (or RNN) should be read. How was RASSD founded, why, and what lessons can we share from our experience?

A new digital news platform is born

RASSD stands for the Arabic words Raqeb (observe), Sawer (record) and Dawen (blog). It was established at the end of 2010 by a group of young Egyptians who had decided to create a Facebook page to provide media coverage of the 2010 elections of the People’s Assembly of Egypt. Most national TV channels were at the time controlled by the Egyptian government. Political parties did not have their own channels except for some newspapers and a limited number of broadcasters from the opposition, namely the leftist and Islamist Muslim Brotherhood.

The emergence of social media created a virtual space for young people that wanted to break the chains of government censorship. We were “virtually free” to let the world know our opinion and the Egypt we wanted. Government control of the media remained, but a platform that could be ours opened up. The birth of RASSD cannot be properly understood without thinking about the connectivity, proximity, interaction, and mobilisation that social media facilitated.

Our first goal was simply to tell people the truth about what was going on in our streets and uncover the electoral fraud we all suspected was taking place. The government wanted to win this election to drum up legitimacy in the eyes of the public. Previous elections were rigged. So we believed this time would not be any different. Our group was mostly made up of students. We were not journalists or majoring in communications. We were of all walks of life and backgrounds. We were medicine, architecture, business management and pedagogy students, to mention a few. Some were employed, others unemployed. Some lived in Egypt and some of us worked abroad.

We all met each other on Facebook. To tell you the truth we did not have extensive experience in media work, and we did not know where the road would take us. In typical youth fervour, we had a firm and almost naïve belief that we had to do something to build a brighter future for our country. The main reason why we embarked on this adventure was that we wanted to induce real change in Egypt. We saw the people on the street as our allies. It was with them that a change could be harnessed, we believed, and by telling and exposing the truth we could galvanise the public. Next, we started to teach filming to those who wanted to report on what was happening, and even how to secretly use mobile phone cameras to document the upcoming election as well as how to use live streaming applications.

In the lead up to the election, we mobilised people through the internet. We ended up creating the largest volunteer correspondent network in memory. We named it “The Field Monitoring Unit: Parliamentary Elections 2010.” This is how we started our e-news network that relied on what we regarded as citizen journalists transmitting the news of our country. We were the people, belonged to the people, and became a voice of the people. We operated under the mantle “From the people to the people”.

RASSD succeeded in exposing the electoral fraud that year, even if the government declared a 99 percent election victory, as expected. Covering the elections gained our page a reputable image for publishing objective facts. This paved the way for a new and an unprecedented type of journalism in Egypt and the Arab world. The events that unfolded in the Arab world during the so-called Arab Spring, starting with Tunisia, became a defining moment in the media landscape and RASSD was well placed to play a leading role.

Online coverage of the Egyptian revolution: RASSD’s Model

After the coverage of the flawed 2010 parliamentary elections, we started strengthening the volunteer correspondent network we had built. We had to rely on people to take good and accurate shots, and this was a challenge. Our main task was to bring to the public the news that we received as professionally and objectively as possible, and most of the time this was being produced by citizens with no journalistic background.

One way to improve our media coverage was by enhancing the skills of our correspondents. We started giving free e-training on mobile journalism and the use of relevant applications, especially Bambuser, to live stream events as mentioned before. We also published a series of articles on how to use mobile phones in journalistic ways, and how to communicate in a safer way through Facebook messages and through emails.

On our platforms, we published videos and pictures taken by volunteers and correspondents. For credibility purposes, we had our own news classification: the news documented with pictures and videos were published under “RASSD/Confirmed/ News” and any news without a picture or a video sent by one of our many correspondents was published under “RASSD/Almost confirmed/ News”.

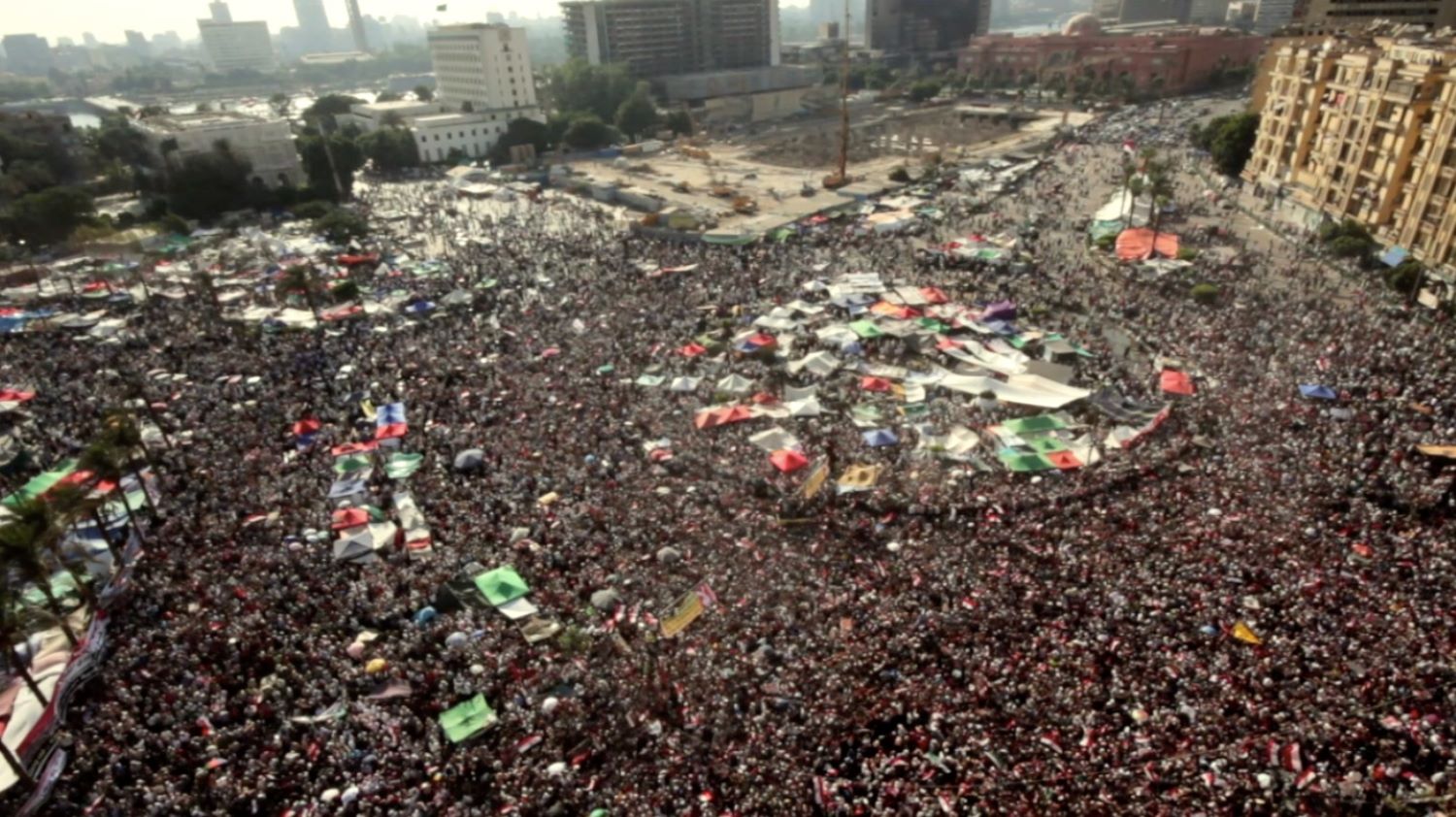

We established a field newsroom in Tahrir Square during the demonstrations. Events were covered online by other teams of correspondents in different Egyptian cities.

On the first day of coverage of the January 25 revolution in Egypt, we racked up 300,000 followers. In the following days, we received more than 20,000 messages from citizen journalists who wanted to talk about what was happening in their location by publishing news on our network. The speedy success became our biggest challenge. We were compelled to stay as professional and objective as possible when covering events. Our biggest achievement at that time was that people started believing they could change things, and that they had a say in what was happening around them. This came as a result of the RASSD pages becoming not only a news source, but also a space for people to interact by discussing and airing their grievances.

Major networks such as BBC, Reuters, Al Jazeera and al Arabiya used some of RASSD's news and photos and followed the network on Twitter. Within days of launching our online portal, our live streaming videos became crucial to global media organisations looking to report on what was happening in Egypt.

We also set up pages in different languages and developed networks in English, French and Turkish, to bring the news to Egyptians who speak these languages. Most of these networks are still covering news in the countries in which they were established. Some have stopped working because of a lack of volunteers.

Another task we undertook was conducting opinion polls on political preferences. Views became clearer for people after they had access to information that was not government-controlled. Our transparency and independence gave citizens the feeling that this was their Facebook page as much as that of the people who administered them.

Problems multiplied when the government cut off the internet and phone services, which was a typical move from the autocratic regime to silence dissent. Media blackouts could choke the momentum. We had to respond and find a way to keep the information flowing to our audience. We decided to set up a team outside Egypt. Its role was to collect and publish the news by accessing our pages on Facebook and Twitter, so our news production and publishing cycle would not depend on the whims of the Egyptian government and its censorship policy.

After covering the uprisings, we established six similar news networks in many Arab countries, all of them built on the concept of the citizen journalist: The Sham News Network in Syria, the Quds News Network in Palestine, the Lightning Network in Libya, the Jordan News Network in Jordan, and RASSD Maroc, in Morocco.

Settling down

Our volunteers gradually became employees. Our operations grew. During 2011, we had launched various news services including flash news notifications on mobile phones. We also had a small income from the sale of our news pictures and videos. These services gave us more financial stability and helped us develop. We set up an office in downtown Cairo and continued developing our correspondents’ skills and capacities, although at a small pace.

We invested in high-tech cameras and equipment to replace our over-used smartphones. Our official website was launched in April 2012. Now a truly competitive and professional media entity, RASSD became a serious player in the Egyptian media landscape.

From 2011 until mid-2013, we expanded and launched our own Radio RASSD. All our efforts culminated in setting up our own media centre, where we managed to train even more citizen journalists. The credibility and reliability we developed helped us launch collaboration schemes with channels like Al Jazeera, and Arab and Global News Agencies like Anadolu Agency, DW News Service, and the Middle East News Agency. Underlining all of this was of course the people’s hunger for real, uncensored news. Without the support of these people and organisations, this would not have been possible.

RASSD after the 2013 Coup

After the toppling of President Hosni Mubarak, covering the news in the field became easier. We were in a new era. The degree of freedom in Egypt was unprecedented but things started to change after the military coup on July 3, 2013.

Killings, arrests, kidnappings and the threat of violence threatened all contributors to our network. This was part of a larger campaign to impose a media blackout on the events taking place in Egypt. RASSD continued to challenge the dominant narrative despite intimidation by all means, by remaining committed to a set of core values: “[…] ethics and codes of honour of journalism, adhere[ing] to the journalistic values of accuracy, balance, independence and integrity, and convey[ing] the truth as it is without any bias or distortion.”

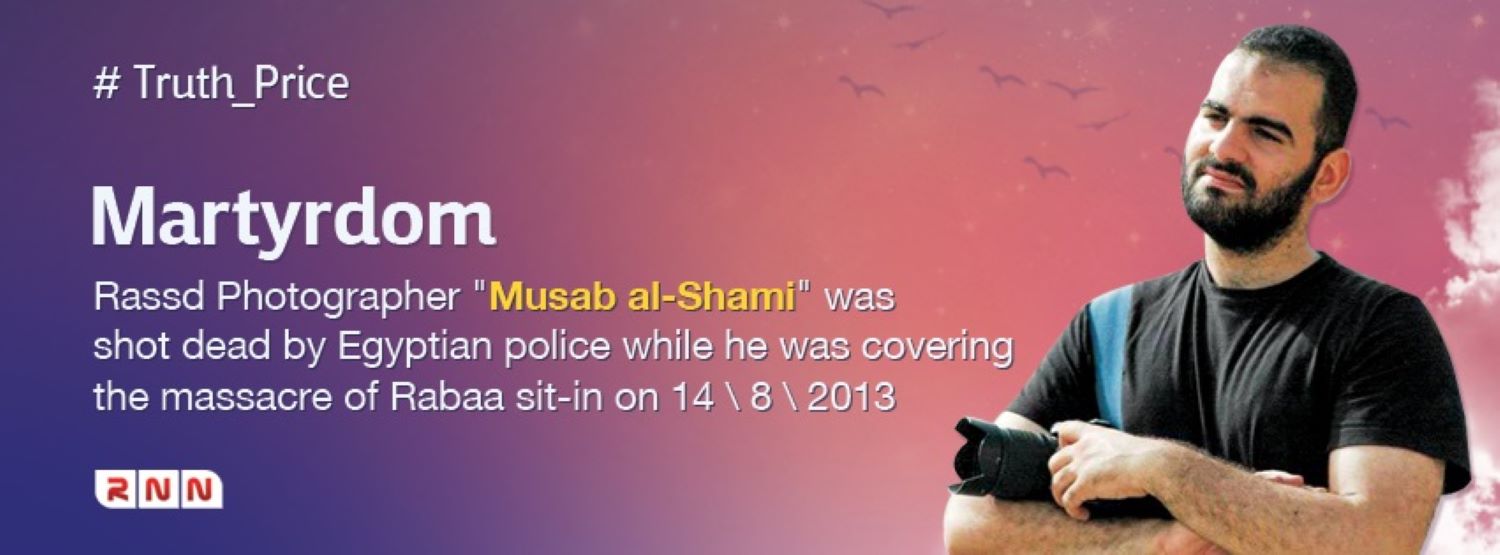

Our offices in Cairo were closed by the Egyptian authorities in July 2013. Our colleague, photojournalist Musab Al-Shami, was killed during the coverage of events in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square. Many of our colleagues were detained. According to Human Rights Watch, “Egyptian security forces’ rapid and massive use of lethal force to disperse sit-ins on August 14, 2013, led to the most serious incident of mass unlawful killings in modern Egyptian history.” Hereafter, covering news grew more challenging. The authorities’ grip on power strengthened. Anyone carrying a mobile phone or a camera and walking the streets became an instant source of suspicion for the authorities. At this stage, the network of correspondents we had across all Egyptian governorates became ever-more important to keep the public informed. However, the government’s brutal crackdown inflicted harm and hampered not only the people’s revolution but also the safety and well-being of our reporters in the field. An iron-fist rule prevailed. Once again, we had to rely almost completely on citizen journalists who risked their lives with every report they posted.

The future

During the political developments and changes in Egypt, our editorial orientations were clear. We supported the Egyptian Revolution, its youth and the figures emanating from it. “After that, RASSD started serving the revolution. Its foundation was linked to the concept of “escalating and directive media” given that it was established at a crucial time - just before the revolution’s outbreak and its live coverage of the Two Saints Church in Alexandria on New Year’s Eve 2011. The people were mobilised to protest against the ruling regime before January 25, 2011, in coordination with the “We Are All Khaled Said” Facebook page, the most famous page to mobilise people against Mubarak’s regime since the killing of young Khaled from Alexandria by the Egyptian police. Khaled became an icon symbolising resistance to the despotism and injustice of the Egyptian police. Thus, RASSD played a major role in covering the revolution’s events.”

It made us more ambitious and willing to challenge our country for the better. The Mubarak regime, and then the Sisi regime, saw us as an oppositional media network. Since the counter revolution, Egypt has descended into a repressive model of governance yet again. Free press and freedom of expression is at its lowest point in years.

The Egyptian regime tried to discredit us by labelling us as biased with political orientations. Many have accused us of being members of the Muslim Brotherhood. It is not my intention to dwell on this argument but rather share with you lessons we learned from our experience in covering Egypt and the Arab Spring. Some have described us as pro-democracy activists. Others highlight that we simply did not report news but instead tried to shape it.

In my opinion, classifying media outlets is not in itself the problem. You cannot be completely unbiased in a political imbroglio like Egypt. For example, the New York Times declared its support for Hillary Clinton during the American presidential election. But the most important thing is to remain credible, objective and ethical in observing journalistic standards when covering events. You have to remain committed to the truth and protect the people’s right to access information. You have to play a key role by highlighting fake and false news. You have to maintain a role in creating a consciousness by raising awareness among readers of the events unfolding in society. RASSD’s experience is an enriching experience for us and our followers. We have learned from our successes, but we have learned even more from our mistakes. We hope our experience can be an inspiration and a springboard for future successes and new experiences in our region and worldwide.

This article first appeared in the Al Jazeera Media Institute publication, Journalism in Times of War