Where once journalists relied on sources for information - also known as ‘human intelligence’ (HUMINT) - they now increasingly rely on ‘open-source’ intelligence (OSINT) gathered from the internet, satellite imagery, corporate databases and much, much more

Many of us know the scene in All the President’s Men, Hollywood’s interpretation of the Watergate scandal, when “Deep Throat” is standing in a car park basement in Washington DC. The man we now know to be the former Associate Director of the FBI, Mark Felt, was the secret informant who gave clues such as “follow the money” to the Washington Post journalist, Bob Woodward.

Finding the evidence that brought down US President Richard Nixon was a watershed event in investigative journalism and has rightly entered its folklore. To break investigative stories in the 1970s, you needed to develop sources.

The skill sets needed for success were once described by the late Nick Tomalin as “ratlike cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability”. Tomalin was killed while reporting the Arab-Israeli war in 1973, a year after Woodward broke the Watergate story. Investigative journalists were usually required to obtain confidential documents from people who did not hand them over without a great deal of persuasion.

The investigator had to nurture sources over time. They’d met in restaurants, coffee shops or late at night in bars. They persuaded whistle-blowers to do the right thing; they gained their trust so that the identity of a source would not be revealed. Managing a source was a critical skill for an investigator.

HUMINT - or human intelligence - was the cornerstone of investigative journalism and obtaining information that no one else had was essential for an exclusive. A journalist usually carried only a notebook and a tape recorder. When I started in journalism, there were no mobile phones. There was little methodology to investigative journalism. Success depended on who you knew and how effectively you exploited them. Then along came the computer and everything changed. Technology altered journalism, both its practice and its consumption.

The roots of OSINT lie in Computer Assisted Research (CAR), which began by exploring and analysing databases. In doing this we can discover patterns, trends and anomalies that may be useful in producing new information. The practical use of this methodology emerged with the Freedom of Information Act in the United States, which was introduced in the 1960s to open the workings of government to public scrutiny.

Philip Meyer, a pioneer of CAR, called it “precision journalism”. It was inspired by the methodology of social sciences where a journalist used evidence to prove his assertion. A methodology was born that inspired a distinct storytelling style that distinguishes investigative from conventional journalism. Conventional journalism is reactive and observational. It describes the world as it is seen, usually after something has happened.

Investigative journalism, by contrast, seeks to prove that some aspect of what the public thinks it knows about the world is wrong. Like a policeman or prosecutor, an investigator will discover a lead or obtain prima facie evidence that supports a hypothesis that “X is lying” or “X is corrupt”. The investigation will aim to prove this supposition. If it can’t, the investigation is dropped. This investigative methodology, known as hypothesis-based narrative, replaced conventional character-based or travelogue storytelling. Evidence gathering became the glue that holds the narrative together.

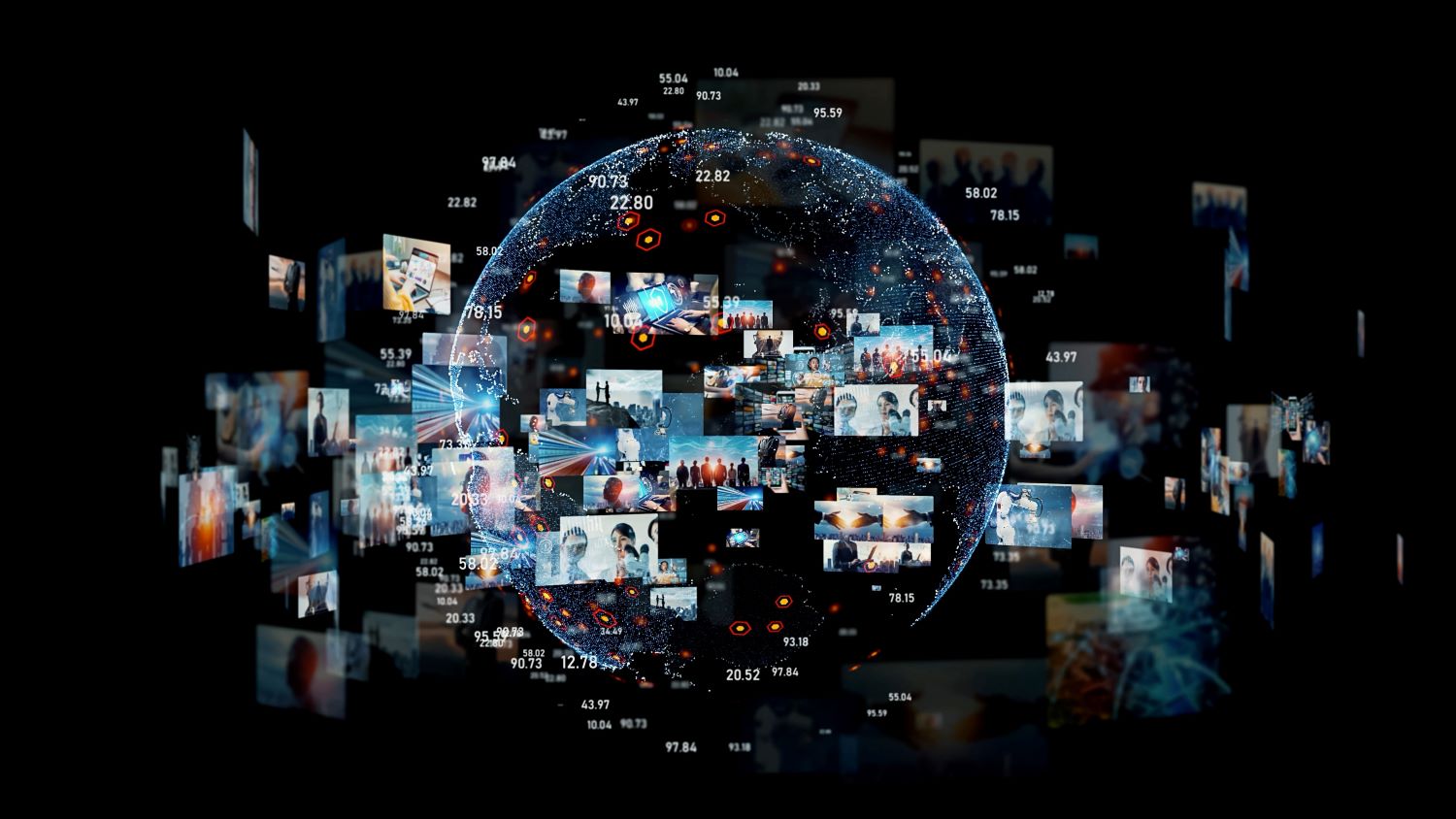

Decades ago, Philip Meyer made the prophetic statement: “When information was scarce, most of our efforts were devoted to hunting and gathering. Now that information is abundant, processing is more important.” In the last decade, open-source intelligence (OSINT) has emerged as a journalistic science, as the vast resource of data collected from social networks and internet-connected devices is mined for information beyond just databases.

The volume of data created, captured and consumed globally is projected to be around 200 billion gigabytes a year in 2025 (up from 70 billion in 2020). Every minute on Facebook, around half a million comments are posted and 150,000 photos are uploaded. More than four million hours of content is uploaded to YouTube every day. Add to that, 700 million tweets per day Investigative journalism will increasingly rely on tapping these sources.

We are not discovering truths that are strictly hidden from us - they are not confidential - but we are assembling information in a fashion that reveals new truths. We are unpicking the resources available online to tell the story behind the picture, the story that the metadata provides, or the story that shipping or flight data tells us about an event.

For filmmakers dealing with investigative content, there are new challenges. There will be more use of computer-generated imagery to tell the story and less use of video. There will be a need to harmonise different sources, such as vertical aspect ratio imagery, publicly generated and low-definition content with professional standards.

Graphic designers, data scientists and filmmakers will need to work together in ways that presently rarely exist. The model of television production needs to adapt to a new method of storytelling. With the amount of information in the public domain, investigative journalists of the future may be less concerned with obtaining secret data than finding ways to make sense of public data, and tell stories based on that. More complex computer-based tools, such as data mining programmes, geographic information systems, demographic databases and so forth can be used to identify patterns, anomalies and discrepancies in data.

Much of the new technology surrounding open source intelligence will involve machine learning, that is when a computer model is trained to analyse data much faster than a human being. In effect, you train a computer to do the hunting for you. It means that investigative journalists no longer need to only learn how to write and turn on a tape recorder or camera. They will need to learn the tools of the internet.

While computer scientists will write the programmes, journalists will need to understand the science of OSINT. OSINT is not a substitute but a complement for HUMINT. For most investigations, journalists need to use human sources as well as data.

Investigative journalists still need “ratlike cunning, a plausible manner, and a little literary ability”. But they also need to understand how to get value from the abundance of information on the Internet.

The Al Jazeera Media Institute Open-Source Investigation Handbook provides an invaluable guide to achieve this.