Transnational repression of journalists in SEA

Trương Duy Nhất, a prominent Vietnamese citizen journalist, disappeared in January 2019 while applying for refugee status with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Bangkok. He was later found in custody in Hanoi. In 2014, Trương was imprisoned for two years for exposing wrongdoing by leaders of the Vietnamese Communist Party on his blog, which led to charges of abusing democratic freedoms. Trương was also a regular contributor to Radio Free Asia, a website deemed an enemy by the state. In 2020, he was sentenced to 10 years in jail for defrauding the public while working for a state-owned newspaper in Danang. Despite international condemnation, his conviction remains unchanged.

Similarly, in 2019, Đường Văn Thái, an independent journalist and member of the outlawed Independent Journalists Association of Vietnam, left Vietnam for Thailand due to threats he received after blogging about government corruption. He was waiting for UN assistance to relocate to a third country when he suddenly disappeared in April 2023. Later on, he was found to have been taken back to Vietnam, allegedly by Vietnamese authorities who were responsible for his disappearance.

In both cases, the home and host countries of the two journalists remained silent and did not face any sanctions, even though there was international condemnation. However, the story of journalists fleeing their countries and being abducted or deported from Thailand, only to be returned to their home countries, is nothing new in Southeast Asia. In 2016, Li Xin, a Chinese journalist who disappeared from Thailand, reappeared in China. Many journalists from Southeast Asia escape their home countries due to a lack of press freedom, only to find that their host countries do not necessarily guarantee their safety either.

Grim mediascape in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is a region comprising of 11 countries with a population of over half a billion people. This region is home to some of the fastest-growing internet economies in the world. As of 2024, around 69% of the population in Southeast Asia uses the internet. With the decline of traditional media, online journalism has become more popular, allowing various actors to enter the field. Journalists have shifted their focus to online platforms, where most information consumption takes place.

Southeast Asia is a region comprising of 11 countries with a population of over half a billion people. This region is home to some of the fastest-growing internet economies in the world. As of 2024, around 69% of the population in Southeast Asia uses the internet. With the decline of traditional media, online journalism has become more popular, allowing various actors to enter the field. Journalists have shifted their focus to online platforms, where most information consumption takes place.

According to the latest edition of Freedom on the Net, an annual survey conducted by US-based human rights organization Freedom House, seven Southeast Asian countries have scored below average in terms of internet freedom. Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia are considered partly free, while Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar are categorized as not free.

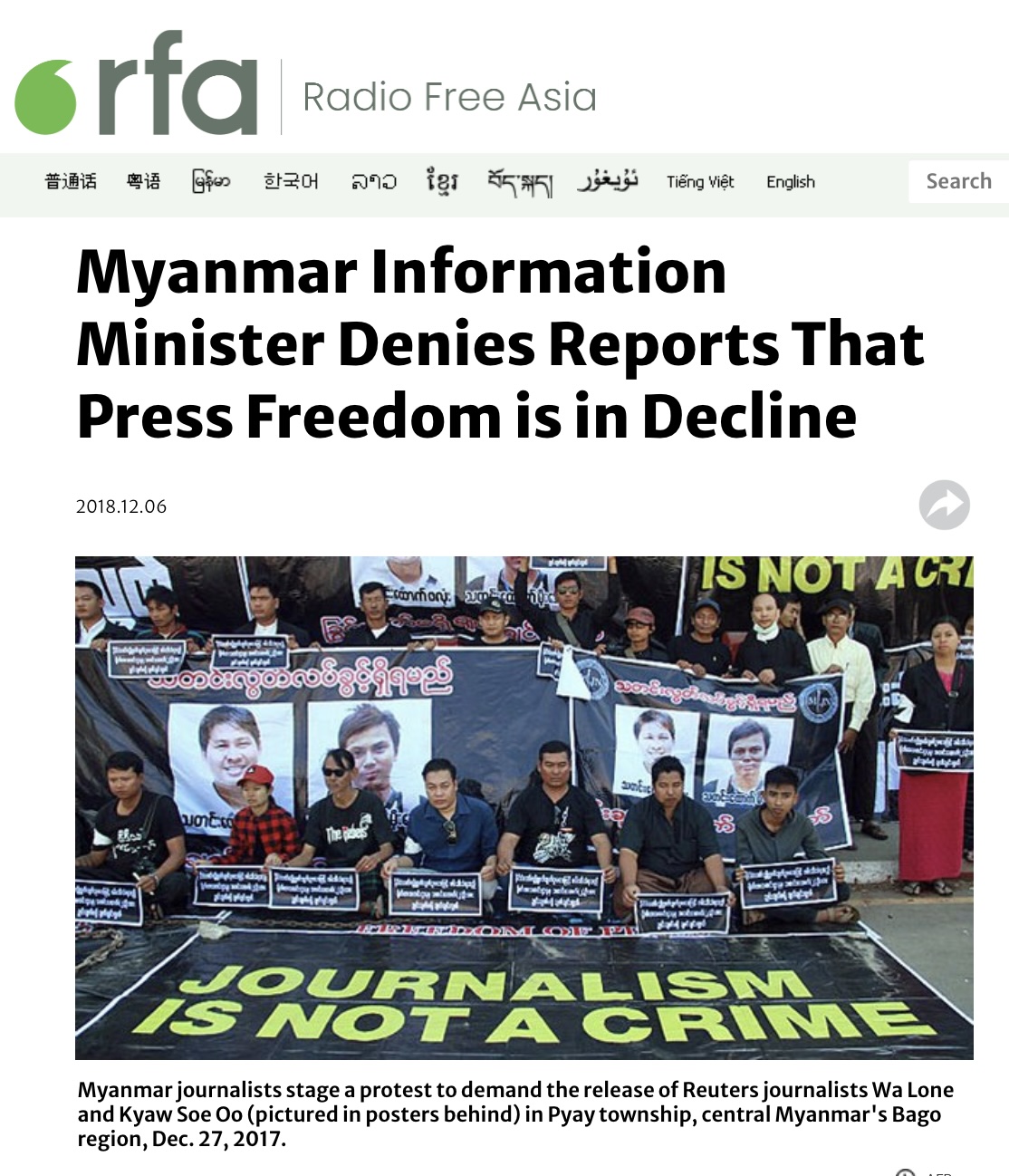

All Southeast Asian countries, except Timor Leste (10) and Malaysia (73), ranked below the top 100 on press freedom, according to Reporters without Borders (RFS). RFS defines press freedom as “the ability of journalists as individuals and collectives to select, produce, and disseminate news in the public interest, independent of political, economic, legal, and social interference, and in the absence of threats to their physical and mental safety”.

The RFS takes into consideration five indicators: political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context, and safety. Thailand (106), Indonesia (108), Singapore (129), Philippines (132), Brunei (142), Cambodia (147), Laos (160) Myanmar (173), and Vietnam (178) are among the world’s worst jailers of journalists in 2023, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based non-profit organisation that promotes press freedom across the world.

No independent outlet is allowed to operate in Laos and Cambodia, while in other countries, independent outlets known for their criticism of governments have been varyingly punished, with notable examples being the closure of Voice Of Democracy in Cambodia or the government blocking of MalaysianNow in Malaysia. Southeast Asian journalists have also practiced self-censorship to alleviate the risks, which are even higher when they write in their own languages.

Restrictive laws have led to a further shrinking of the internet and media space in the region. Dr. James Gomez, director of Asia Centre, a not-for-profit social enterprise that undertakes evidence-based research on human rights issues, listed three major types of severe yet vaguely worded laws that have been created in recent years and used to punish journalists: 1) national security-related laws, 2) technology laws, and 3) anti-fake news.

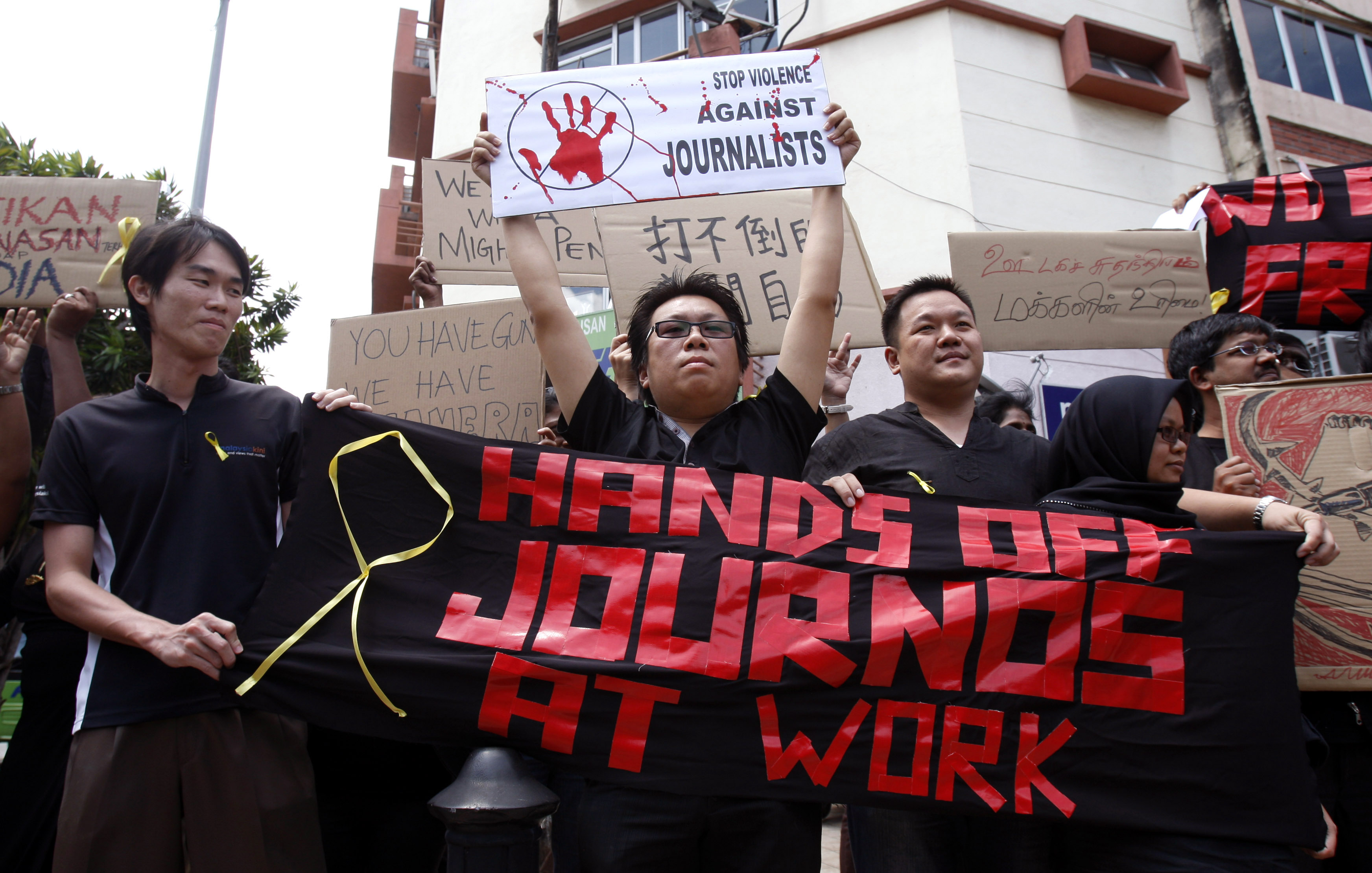

Major news organisations have reported more challenges accessing the region. In 2020, the Al Jazeera office in Kuala Lumpur was raided by Malaysian police, a top-down move that was widely decried by the international community.

The Rise of Citizen Journalism

Studies have shown that citizen journalism has been on the rise across the region, thanks to the advent and advancement of technology. Yet, their governments range from partial recognition, such as Indonesia, to crackdowns, as in the case of Vietnam.

Dr Mastura Mahamed, Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication University Putra Malaysia, says that freelance journalists and citizen journalists have a symbiotic existence among Southeast Asian countries, though they are different, mostly due to the formality of media education and exposure. “A freelance journalist is Someone with academic credentials in knowledge and practice on journalism and media principles. It's just that they do it as freelancers rather than being hired by a specific media organization, says Dr Mahamed. “A Citizen journalist, on the other hand, is someone without formal knowledge and exposure to the media industry”.

Dr Mahamed, a former independent journalist, explains that citizen journalists follow basic journalistic practices such as the 4Cs (1) Create ideation, 2) Collect information, 3) Construct the article, 4) Correct and cross-check to share news about their concerns and happenings around them. “These citizen journalists have different careers as a full-time jobs. Often, these citizen journalists use personal social media platforms as well as community pages to share their news articles”, said Dr Mahamed. “Some of these articles usually will get picked up by professional journalists in media outlets and this will increase the news coverage”.

However, according to Dr Mahamed, this kind of symbiosis has happened in many instances but it is more widely discussed academically in Indonesia as it has more collaborative platforms between professional journalists and citizen journalists. In many countries across the region, independent media have been declared by the government as enemies. Journalists and outlets from Myanmar, and Vietnam have to be exiled to uphold their editorial autonomy and personal safety.

Unsafe Overseas: Threat to Exiled Journalists

Currently, those seeking refuge by crossing borders irregularly are irregular migrants. Non-interference is a key aspect of the ASEAN way, as reflected in the ASEAN founding treaty of 1976. The Bangkok Principles on the Status and Treatment of Refugees is the only existing normative framework for the protection of refugees in Southeast Asia, albeit non-binding. In May 2021, three journalists who worked for the Democratic Voice of Burma news website and crossed into Thailand to flee a military crackdown were arrested in the northern city of Chiang Mai. They were charged with illegal entry. The three journalists have been reportedly granted asylum in a third country.

There has been growing pressure from China, one of the key perpetrators of transnational repression at the global level, along with Russia, Iran, and Rwanda to demand the return of critics overseas. In 2023, exiled Chinese journalist Yang Ze Wei was kidnapped from his home in Vientiane, Laos.

Since the coup in 2021, it is estimated that at least a thousand Burmese journalists have been living in exile, with a third of them residing in Thailand. Unfortunately, many of them lack refugee protections or the necessary legal status to pursue professional or educational opportunities. A common scenario among many exiled journalists in Southeast Asia, specifically in Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia, involves the surrendering of political dissidents to neighbouring states. This practice flagrantly violates the customary international law protections established to safeguard the rights of refugees and asylum-seekers.

Trinh Nguyen, a security trainer with extensive experience working with Southeast Asian activists and co-founder of Rise, a US-based organization that supports social movements in Vietnam, emphasizes the importance of focusing on intelligence sharing among Southeast Asian countries. “There's been a long-standing formal and informal practice to share intelligence between those countries”, said Nguyen.

In more extreme cases, dissidents seeking refuge in these countries seem to be forcibly "disappeared" from their intended place of safety, only to resurface weeks or months later in the custody of another state. These incidents raise serious concerns about the blatant disregard for the well-being and rights of these individuals.

It is crucial to address these human rights violations and breaches of international law. The protection of refugees and asylum-seekers, as well as the adherence to principles such as non-refoulement and the right to seek asylum, should be respected by all nations. The occurrence of such incidents emphasizes the urgent need for increased attention and action to ensure the safety and rights of political dissidents in the region.

Except for Cambodia and the Philippines, most countries in Southeast Asia have yet to accede to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. Since mid-2022, Malaysia has expedited the deportation of Myanmar refugees back to the junta-ruled country and even told the UN not to interfere in its policy.

Yap Lay Sheng is an associate who works as a Human Rights Defender for Fortify Rights, which is a non-profit organization that supports human rights defenders and affected communities. According to Yap, Malaysian immigration laws do not differentiate between undocumented migrants and refugees. This means that deportations can happen without assessing the asylum claims or protection needs of refugees. As a result, this puts many with prior human rights backgrounds, who have fled to Malaysia to seek safe harbour, in danger.

Yap stresses the importance of respecting the 1951 Refugee Convention, which obligates governments in Southeast Asia to respect the rights of refugees. "Whether these states do so in cooperation with foreign governments or otherwise, governments in Southeast Asia are obligated to respect the 1951 Refugee Convention”, said Yap.

Dr Sebastian Moretti, Senior Fellow at the Global Migration Centre of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies and author of the 2022 book” The Protection of Refugees in Southeast Asia: A Legal Fiction? says that exiled journalists represent a particularly vulnerable category of people insofar as they are at high risk of being arrested and deported as “irregular migrants” in many countries across Southeast Asia, despite a risk of persecution in their countries of origin due to their political activities.

“Clearly at-risk exiled journalists should be considered or treated as refugees by countries where they have found refuge, if not de jure (many countries in Southeast Asia are not parties to the Refugee Convention), at least de facto, which means that they should not be arrested and detained for irregularly entering a country (if that’s the case), and, even more importantly, they should not be sent back or deported to their countries of origin, as this would represent a violation of the principle of non-refoulement under international refugee law”, says Dr Moretti. “Any country sending back people to their country of origin despite a risk of persecution and/or torture should be held accountable for whatever could happen to the concerned persons”.

Insecure Digitally: Censorship and Surveillance

Big tech companies even colluded with governments to consolidate top-down censorship and arrests of journalists. Meta, which provides a platform for citizen journalists in Vietnam to voice their concerns, has an internal list of Vietnamese Communist Party officials who can not be criticized on Facebook.

Furthermore, cybertroopers who are paid by the government to counter oppositional narratives or spread hateful content have been on the rise. “It is also important to note that content creators, keyboard warriors, and cyber-troopers are NOT considered citizen journalists as they do not use journalistic processes in writing articles”, said Dr. Mahamed.

According to Nguyen, whose work focuses on monitoring threats, at-risk journalists can protect themselves by minimizing sensitive data by using disappearing messages like Signal; regularly updating devices and software; and not clicking on unsolicited or unexpected messages. iPhone users can turn on Lockdown Mode for enhanced security features. “In addition, those who have been targeted should reach out to human rights organizations like Amnesty Tech or Citizen Lab for advanced analysis and support”, adds Nguyen.

In conclusion, the transnational repression of journalists in Southeast Asia poses a significant challenge to press freedom and the protection of refugee rights in the region. Addressing these human rights violations and strengthening the legal frameworks for refugee protection should be a top priority for governments and international organizations.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera Journalism Review’s editorial stance