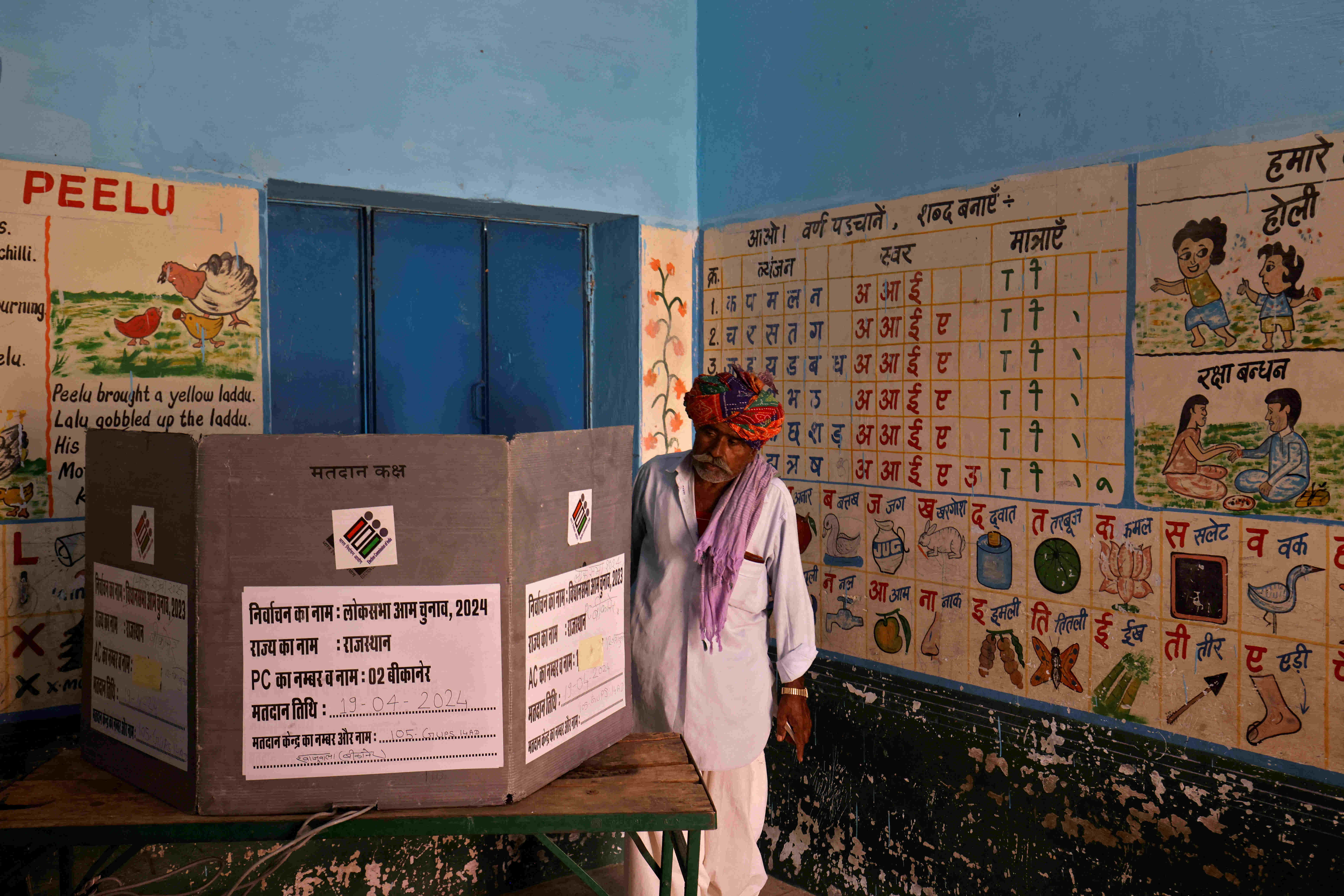

This year (2024), over 2 billion voters spanning 50 nations, including significant democracies like the United States, the European Union, and India, are poised to participate in a historic wave of elections worldwide. These elections are not only crucial for people but it’s difficult as well. They need to form opinions about who to vote for by pulling themselves through a pile of misinformation and disinformation. For elections to be fair, people need to know the truth. When they have the facts, they can make up their minds about who they want to vote for.

Nowadays, a lot of people get their information from social media, especially through WhatsApp which helps political parties and politicians to easily spread lies and fool voters with fake information. This makes it hard to have fair elections because the truth gets mixed up with lies. In the 2019 Indian elections, a lot of fake information was spread, especially online which not only shaped the political opinion of the people but also resulted in physical violence. Now, the way technology has evolved, the process has changed super fast. Big companies that run social media are having a hard time stopping fake news and distasteful ads. Back in 2019, people worried about deepfake videos, but now it's even easier, better, and cheaper to create them due to new technological evolution.

According to the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risk Report, India is the country where the risk of disinformation and misinformation was ranked highest. Another Survey conducted by Social and Media Matters, a digital rights organisation revealed through a study that nearly 80% of India’s first-time voters are bombarded with fake news on popular social media platforms and 65.2% of the respondents will be casting their votes for the first time.

Types of misinformation & impact on elections

AI-generated content: AI-generated content looks real, is good, and is easy to use. Political parties use it to quickly make fake content to aim at voters and change their perception as to how they vote. AI-made content creates new problems for India’s voters in 2024, just like how WhatsApp was full of wrong information before the 2019 General Elections.

Fake News: Fake news is when people say things that aren't true and act like they are. This can be made-up stories, tricks, or things that are meant to fool others. For Example; addressing a gathering in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi accused the Congress of a plot to ‘take away assets’ of people and redistribute it among others. Now this speech created a lot of buzz among the masses and till Congress reacted to the speech, people consumed this information as a fact. Now this kind of fake news does make an impact on people’s minds and shapes their opinion as they live in rural areas, are old, and do not understand the political dynamics. Mishi Choudhary, who is a Technology Lawyer and founder of SFLC.in. explained that the problem lies in a tendency of society to believe that information is truthful just because it appears on various platforms. “This belief is a result of a legacy of trust that was once placed in traditional forms of dissemination of information. Unfortunately, this misplaced trust has created a dangerous vulnerability that political actors have exploited to sow confusion and undermine trust in the media landscape. As a result, a pervasive atmosphere of doubt and scepticism has taken root, eroding public confidence in the veracity of information disseminated through any channel.”

Satire/Parody/Memes: Content that is meant to be funny or make fun of things, but some people might think it's real news. Even though satire isn't meant to trick anyone, sometimes people don't get the joke or share it without understanding. On February 20, India’s chief opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC), uploaded a video parodying Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Instagram that has amassed over 1.5 million views. Even though these are usually seen as just funny, they can also be used to share information or bring people together. That's because memes can affect things outside of the internet, too. In reality, memes can even help people talk about important topics as they target Gen Z

Case Studies and Prevention methods to curb mis/disinformation

For this piece, we spoke to journalists about how they cross-check information and what are their standard practices to prevent mis/disinformation. While it became clear that they use a lot of research and ground reporting, it also became clear that journalists need to be extra cautious in balancing the need to report facts while avoiding sensationalism and bias. Every decision they make on what to report and how to frame it carries significant implications. Therefore, they need a nuanced understanding of the socio-political landscape and a steadfast commitment to upholding journalistic integrity.

Conduct Thorough Fact-Checking of Political Rhetoric

Parvathi Benu works at The Hindu Businessline based out of Chennai. Parvathi is covering elections as the paper has started a dedicated page for election stories.

For Benu, navigating the realm of political campaigns in South India isn't just a challenge; it's a fascinating journey into the heart of local democracy. “As I immerse myself in these events, I've come to recognise the significant role that local politicians play in shaping public opinion — often through the dissemination of misinformation.”

In the bustling chaos of election campaigns, Benu observed a common pattern: scheduled events starting late, with opportunistic speakers filling the void with their rhetoric. These local politicians, while passionate and engaging, often possess only vague insights into national affairs, paving the way for misinformation to take root.

“In a recent encounter with a political critic of the Modi government passionately aired his grievances about pressing national issues such as electoral bonds, he veered into territory fraught with inaccuracies regarding the Ayushman Bharat scheme,” Benu explained how at that moment, she felt compelled to intervene, gently steering the conversation back to the factual ground and correcting him about the issue ensuring that truth prevailed over political rhetoric.

Benu also feels fortunate to work within a newsroom culture that places a premium on accuracy and integrity. “I am allowed to conduct thorough fact-checking before filing my reports, ensuring that the truth remains unchallengeable in the face of political discourse.”

Parvathi's explanation deeply resonated with Choudhary, the founder of SFLC.in. She highlighted how a concerning pattern has emerged over time, where political parties and their supporters, who often act as cheerleaders, become the primary purveyors of misinformation and disinformation. “These actors have a significant influence in shaping public perception, whether intentionally or unintentionally through ignorance. Their tactics include spreading falsehoods and manipulating narratives to serve their interests, with the active participation of supporters, campaign participants, candidates, and the intricate network of IT cells affiliated with various political entities.”

But in the current atmosphere of polarisation in India where journalists and media houses have slowly died, only a few independent media houses and journalists are left to hold the press high and safeguard the freedom of speech and democracy in the country. Political parties especially the ones in power use all their power and will to spread misinformation through their campaigns be it about policies, promises, or schemes.

Verifying Information Through Rigorous Triangulation

23 years old, Meer Faisal proudly identifies himself as an independent journalist driven by a relentless passion for truth and has been reporting on complex issues and dedicating his efforts to shedding light on Hindu nationalism and the pervasive violence against Muslims. With a steadfast commitment to uncovering the unvarnished reality.

Apart from debunking fake information and reporting from the ground Faisal also has to remain extra cautious before publishing anything “As a Muslim journalist, navigating the turbulent waters of media comes with its own set of challenges. The constant threat of online harassment from trolls and the looming spectre of being targeted by authorities underscore the need for unwavering caution and meticulous verification of information before publication. Aware that any oversight could be weaponized against me, I approach my work with a heightened sense of vigilance, leaving no room for error.” said Faisal who reports for different publications.

In this delicate balancing act between truth-telling and self-preservation, Faisal prioritizes professionalism and due diligence over anything else. Each piece of information undergoes rigorous triangulation, ensuring accuracy and reliability before it sees the light of day. This commitment to thoroughness not only safeguards him but also upholds the integrity of his reporting.

Faisal also sheds light on propaganda created by different political parties through WhatsApp and other channels “Unlike journalists with close ties to governmental sources, I am not swayed by the allure of WhatsApp forwards that serve as thinly veiled propaganda. Recognizing their potential to skew narratives in favour of those in power, I remain steadfast in my dedication to uncovering the unvarnished truth, free from external influence or manipulation.”

A seminal research paper published by the Center for News, Technology, and Innovation (CNTI) sheds light on the intricate dynamics surrounding legislative responses to combat misinformation and disinformation. CNTI conducted a comprehensive analysis of legislation across 31 countries. The findings, however, paint a sobering picture: while purportedly aimed at safeguarding the public discourse, such legislation often falls short in protecting journalistic freedom. Far from mitigating the risks posed by misinformation, these measures can inadvertently exacerbate them, amplifying the potential for harm.

Analysing Government Claims Through Ground Reporting

Among the various methods used by journalists to verify information for their stories, journalist Shreya Raman is distinguished by her unwavering dedication to accurate reporting. For Shreya, fact-checking goes beyond simply confirming details; it represents a deep sense of accountability. With a sharp attention to detail and a strong curiosity, Shreya thoroughly investigates not only the government's official statements but also the concrete actions taken.

Her recent interest is in understanding how the BJP government, which has been in power for a decade, makes numerous claims. One claim that particularly piqued her interest is the "Lakhpati Didi" scheme, touted by Prime Minister Modi in his recent Independence Day address. This scheme, highlighted as a milestone in women's empowerment, purportedly transformed one crore women into "lakhpati" individuals, as reiterated by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in the budget.

Determined to unravel its true essence, Shreya embarked on a journey to Madhya Pradesh, seeking firsthand insights into the reality behind the rhetoric. “In my quest for clarity, I discovered that the Lakhpati Didi scheme is intricately tied to the National Rural Livelihood Mission, wherein women within self-help groups are bestowed with interest-free loans to start their entrepreneurial ventures. Yet, amidst this facade of innovation, I encounter a stark disconnect between official proclamations and grassroots reality.” Shreya said, “Meeting with women who are active participants in these self-help groups, I am met with a perplexing revelation—none of them possess any substantive knowledge of the purported Lakhpati Didi scheme.”

Another way of researching and connecting dots to fact check for Shreya is to use a lot of standard practice which is to Google extensively to find any bit of information and try to place that together with interviews on the field.

“I know it’s not easy for all journalists to conduct ground reporting but until and unless you are meeting people and figuring it out it’s very difficult to tackle these kinds of claims.” Shreya highlights that her approach has been to check these claims and understand them through ground reporting “When they claim India is open-defecation-free, what do they mean? It means all the households now have toilets, but does that translate into installing usable toilets with all the necessary infrastructure, like water? Does it translate to behavioural change? What I do is I check these claims and try to debunk them.”