The function of news, according to the Western literature, is to inform the electorate (referred to as ‘readers’, ‘viewers’, ‘followers’, or sometimes ‘consumers’) so that they can vote rationally and hold to account those they vote for. Anything else is simply an additional detail or an elaboration of this basic function.

As it has come to be understood in the West, this function is based on the idea that well-informed citizens can vote in such a way as to serve and preserve the established order (liberal democracy, free market economics, technological determinism). Likewise, they are able to observe the consequences of how they vote, thereby “linking responsibility with accountability” as the well-known Arabic expression has it.

This idea, reproduced across the globe, has been promoted as the ideal model and the final form of serious journalism, in a way that closely resembles the thesis of the “end of history” and the victory of liberal democracy with the end of the Cold War. This thesis famously suggests that having triumphed over the “ghost” of Communism and Socialism with the fall of the Soviet Union, liberal democracy has become the only universalisable model – implicitly invalidating any proposal originating in the periphery.

The dialectic of the periphery

The global periphery—sometimes referred to as the global south or developing world—may be in some form or another the product of the established order, but it also challenges the tradition, which over the years, has transformed into a rigid ideology suppressing any alternative materially or morally. Take for example what is sometimes referred to as citizen journalism. Citizen journalism has benefited from the techniques produced by this system to move beyond pre-established paradigms in journalism, forcing periphery media to allow the “core” to come in through the window after closing the door in its face.

Those in the periphery, and especially in the Arab World, are professionally enthusiastic about this model. We learn it and sing its praises, but do not necessarily succeed in applying it. This is not because we lack the competence to, but because we work under different conditions.

Professional Arab journalists seek to inform a hypothetical voter, but we have neither elections nor an electorate. Many try to produce reports and investigations in such a way as to “link responsibility with accountability”, or simply to hold people to account. But it is rare, very rare, for this to actually happen. In practice, there is nobody with responsibility from whom we can extract accountability.

Some attribute this professional “failure” to Arab readers’ lack of interest and falling levels of “awareness.” Others who consider themselves “true professionals” believe a lack of professional standards in the Arab world (standards defined in the West) is preventing true accountability from being achieved. Invariably, when a western journalist’s investigation meets with acclaim simply because they are western, the latter crowd will direct derisive questions inward in a criticism of our own journalistic competence.

Still, others suggest the issue is that we are not translating our work into a global language, since our officials can only really be held to account by Western regimes, rather than by the people they supposedly serve. However, this suggestion does no more than conceal the problem of a local “illness” with imported language.

It would be naïve to claim that media can exist entirely separate from politics, and that journalism is always purely professional, objective and neutral. The media is indisputably politicised. It is a political tool when it takes sides and a political tool all the same when it remains neutral.

Even the Western journalistic tradition, presented today as the paragon of independence, has its functions; nobody can sincerely claim otherwise. Western journalism is proud of its role as the “fourth estate” and works to serve the voter, which is a political function. The media can also be recruited quite bluntly (which is not to say this is necessarily a bad thing) to political causes in times of crisis. Consider for example the role played by the US media after the events of September 11 2001, or the slogan adopted by the Washington Post and the rest of the liberal media after the election of Donald Trump (“Democracy Dies in Darkness”).

Changing the agenda, not rearranging It

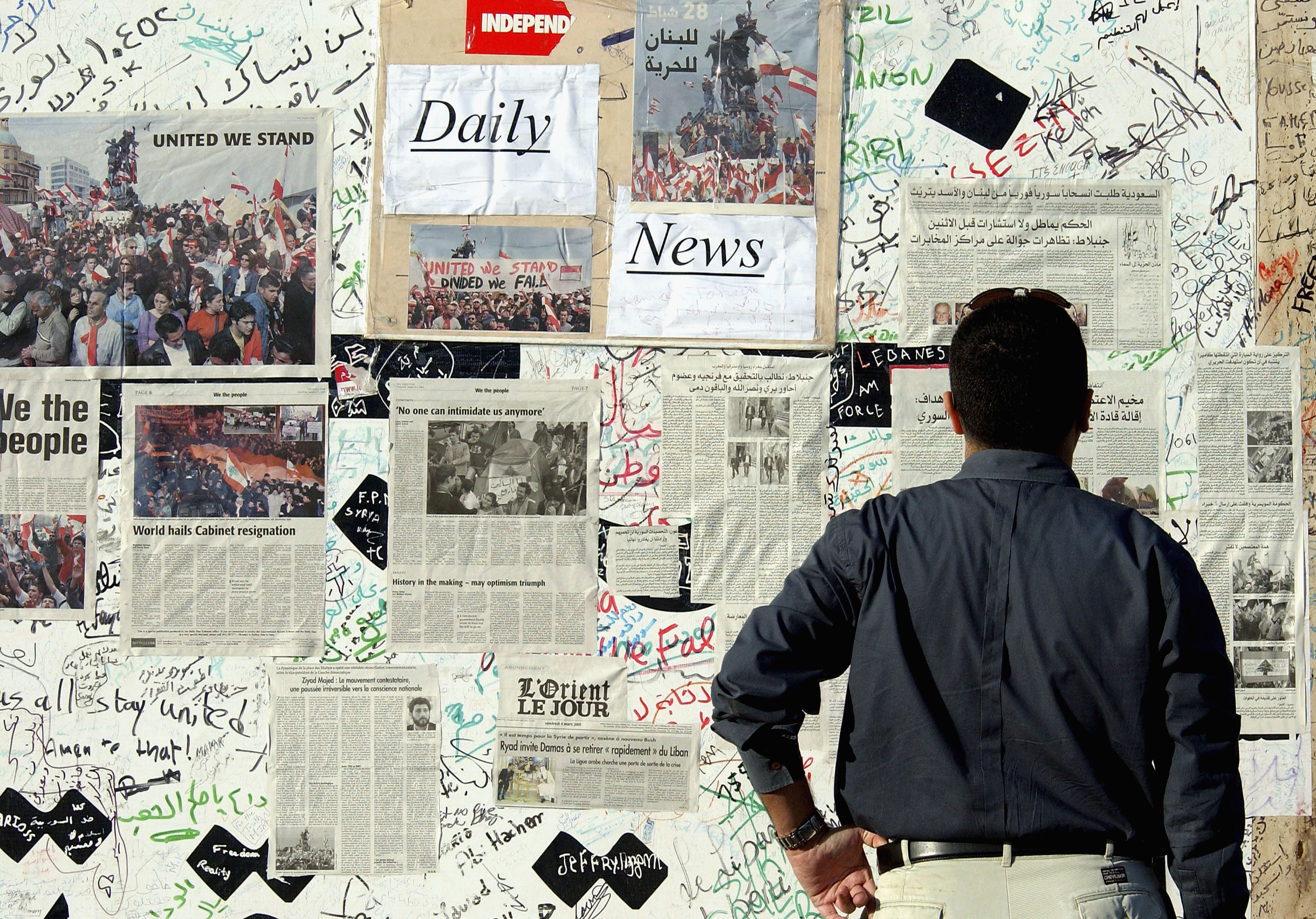

When we concede that the media is inevitably political (which is neither a new nor a dramatic concession to make), it becomes only logical that the media of the Arab World has its own political agendas. Arab newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s claimed to have a pure regional focus, despite essentially being party organs masquerading as political newspapers. Likewise, a favourite claim of the cable news revolution was that it was bringing the voice of the region to the world using the tools “agreed upon” the world over– but this too was mostly a self consciousness borne out of the “us” vs “them” rhetoric employed worldwide. The political role of Arab media media was once again brought to the forefront during the 2011 Arab spring, before losing its way in the “post-Revolutionary period.”

Shortly thereafter, web journalism, citizen journalism and blogs appeared on the scene. People picked up cameras and rushed to their keyboards, documenting the historic events taking place around them. They wrote, filmed, discussed, published and tweeted with purpose, simultaneously mocking both vulgar partisanship and closely-confined professionalism. It was a lively time with many positive sides to it. But it quickly became clear – particularly after the shock of the counterrevolution – that this option was little more than an impotent screech of rage that acted solely as a catharsis, rather than creating a new mode of politics.

Together, the older generation of traditional media and the younger generation of internet journalism produced a “rationalist” mixture which seemed to understand the dangers posed by both models. Instead, the two generations sought to create a fourth model, combining the professionalism, history and standards of news TV and the bravery and novelty of web journalism.

But after a virtual life lasting no more than five years (taking the Egyptian revolution as its moment of birth), the genre has been turned into little more than superficial entertainment. Today, this “rationalist” coverage mostly focuses on individual salvation, identity politics and other current global themes, or simply reproduces content produced in the West. Many names have been employed to describe this new form of journalism, including: narrative journalism, slow journalism, content journalism – or even long-form journalism. However, this genre of journalism is still taking shape and it is far too early to make any reliable predictions on its future success.

The search for a solution: A return to politics?

Developments in Arab media are generally catalysed by one of two events: 1) a change in journalistic media, or the introduction of new technique or form, or 2) a rearrangement of the political agenda of outlets or the political context they work in. The problem in Arab journalism might lie in the latter event. Instead of rearranging the priorities of media outlets every time there is a political crisis, entire editorial processes need to be overhauled based on discussions that include more than just a narrow circle of media professionals.

This time, we are on our own. We will not find any useful discussions or guideposts from the West to import, as they went through this process decades ago. They fought financially, legally, and morally to ensure an independent press, and today they are elaborating on their conceptions on such a press. We cannot start from this stage, we must start the discussion from scratch. To begin we must ask broad questions that get to the heart of what the Arab World needs to determine, such as: What are politics? What do we want from them? Where do we begin?

However, we will not truly be starting from scratch, as we have 120 years of accumulated journalism from which we can surely extract some useful lessons. By taking the aforementioned questions as points of departure, we can begin to understand our historical “inheritance” and decide what we want to take with us moving forward and what we want to leave behind. This will not be easy for media professionals to have–indeed, it may prove a bitter struggle, but it is a necessary one.

Though the process overhauling the Arab media scene should be more concerned with ends, rather than means, it is still worthwhile to include journalistic techniques in our discussion. “Data-driven journalism,” for example, is generally made possible by the vast amounts of data made available by governments in democratic societies, or via Freedom of Information requests. Even when this data is available in the Arab world–which is rare–it is not necessarily trustworthy. Arab journalists thus have to bear a double burden: acquiring data (with difficulty), examining and sifting through it, and then finally, proceeding to analysis.

It is only through this process of evaluation and re-evaluation that we can decide what we ought to keep moving forward and what we must be rid of. This process and debate will be ongoing for some time before a conclusion is reached. Until then, we must remember one thing: We must not be ashamed of the term “politicised” media simply in the name of supposed neutrality. This will be our choice, the choice of the “periphery.”