Reporters like to say that they’re telling their audiences the facts, that it is up to the audience to decide what the facts mean, and what they should do about them. But there at least two very long traditions in journalism that view the job differently.

One of those traditions began with the Puritan revolutionaries of the 17th century. Their newspapers were designed to build, discipline and sustain a political movement. American revolutionaries did exactly the same thing in the 18th century, and Russian revolutionaries did so in the 19th and 20th centuries. Radio Rozana, the voice of the Syrian revolution in Paris, is a direct descendant of that line.

The other tradition, reformist rather than revolutionary, began in the US and UK in the late 19th century, and is lately known as investigative journalism. Investigative journalism exposes secret or simply overlooked facts to justify change. The change could be forcing a corrupt official to leave office, or to undo a bad law, or to invest more in certain kinds of public goods. Not all investigators become advocates of reform, but all of them are judged (at least in the eyes of their peers) by whether their work does, in fact, lead to change.

In contrast, “objective” news reporting is a relatively recent invention. Professional standards in the US were modified to make objectivity – meaning fairness, a lack of bias, and strict accuracy – a central feature only in the 1920s, after the “muckraker” Upton Sinclair exposed the deep and wide corruption of the press.

The use of mass media as a vehicle for propaganda and repression in Nazi Germany terrified contemporaries; following World War II, news managers tried to distance themselves from that model. In the 1960s, the stunning power of television to influence public opinion reinforced the demand from political elites that news media stick to transmitting “information” – the facts and nothing else. There was, of course, an argument over which facts were worth revealing, but there was much less controversy over whether reporters should say what the facts mean. Probably everyone reading this article was trained to report the facts, and leave the commentary to editorialists or talk show guests.

Of course, it is impossible to be purely or entirely objective. The founder of the CBS network, William S. Paley, once complained that the anchors on CBS News always, inevitably, were drawn to stating their own opinions, influencing the interpretation of the news. But that’s not the issue here. What concerns us are the forces that are driving news media, everywhere, from objectivity toward reformism, and how we can best deal with that conflict.

Stakeholder-controlled media

Let’s not pretend this isn’t a conflict. In 1990 reporter turned scholar Robert Mirandi wrote a book whose title captures the dilemma: Objectivity and Muckraking: Journalism’s Colliding Traditions.

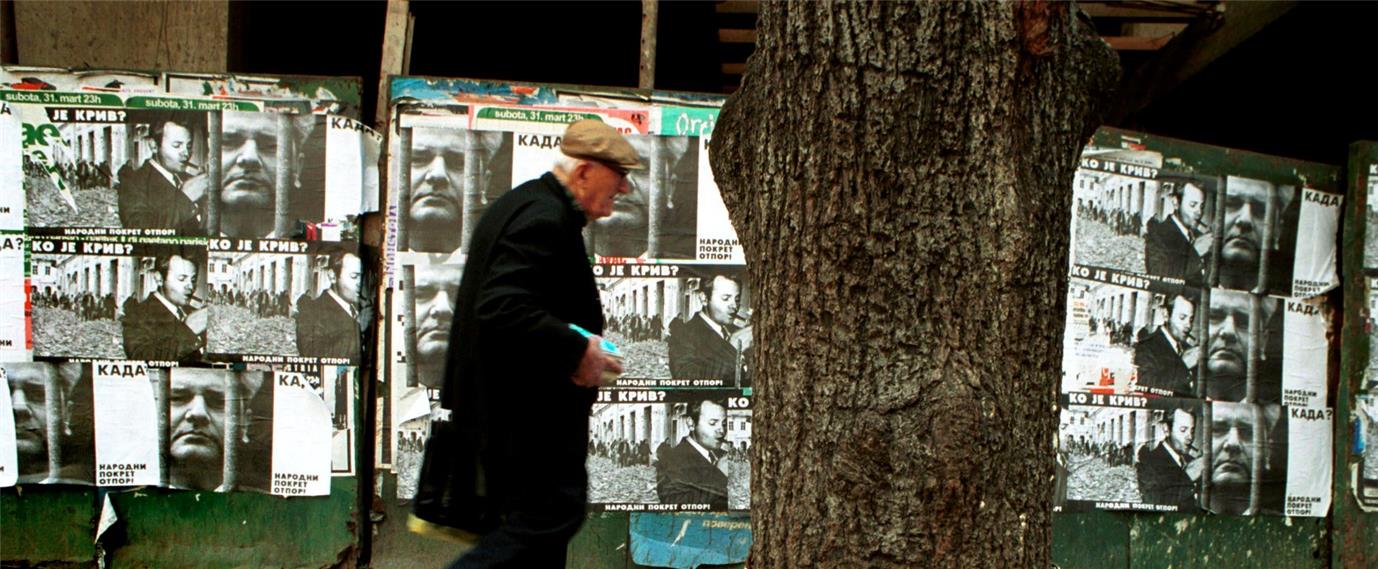

Mirandi argued that telling facts without ulterior motives, while fine in itself, is an inadequate standard for reporters faced with injustice. Before the decade was over, the issue migrated to the centre of news reporting. The driver was Slobodan Milosevic, the Serbian dictator who invaded his Balkan neighbours following the collapse of Tito’s Yugoslavia. The journalists who launched their careers in that conflict, notably Christiane Amanpour of CNN, made little effort to conceal their conclusion that the Serbs were cruel aggressors who must be stopped. (Amanpour famously challenged Bill Clinton to do just that.)

Another challenge to objectivity came from outside the news industry. The key driver was Greenpeace, which announced in its 1995 annual report that henceforth, the militant ecological group would also function as a media production house.

That same year, Greenpeace activists carried video cameras as they invaded the Brent Spar offshore oil well in the North Sea. Those images brought Greenpeace’s message directly to television networks, multiplying its impact. Meanwhile, America’s fundamentalist Christians were organising their own radio and TV networks, to counter what they considered the leftist bias of mainstream US media. (Fox News, which bizarrely calls itself “fair and balanced”, is a direct descendant of those networks.)

With the arrival of Internet, anyone who doesn’t like the way news media reports their stories can report for themselves. Of course many of these new media display little or no professionalism, and care little about what is true. But a growing number are very professional, and highly influential.

At the INSEAD Social Innovation Centre, a research unit at the global business school, we refer to this new media as “stakeholder-controlled media.” My colleagues and I have documented cases in which these media destroyed units of multinational firms through their coverage. They were crucial to making climate change a global issue, decades before news media covered the story in any depth. Their leadership on such issues is surely a main reason that viewers find them credible.

Whatever the format they use – Facebook, YouTube, websites, podcasts – stakeholder-controlled media share four characteristics that distinguish them from news media like Al-Jazeera. They aren’t objective, they’re transparent; they tell you what they want. They not only tell you what matters, they also tell you what to do about it. They are less concerned about the general public than about people who are focused on the same issue. And, finally, they are deeply concerned about the past and future of the subjects they follow, as well as the present.

These media are impacting the news industry in a growing number of ways. First, they are providing the downsized industry with a key resource – namely, powerful information. A growing share of the investigative capacity of the news industry is migrating into stakeholder-controlled media.

When New York State officials opened an investigation into the oil company Exxon Mobil, for allegedly lying to its shareholders about climate change, the drivers were Greenpeace and Inside Climate News. The Volkswagen emissions-scandal began with a report from a previously obscure group, the International Council on Clean Transportation. Even the New York Times, Financial Times and Washington Post publish investigations co-authored by non-profit groups like ProPublica, The Marshall Project and the Kaiser Foundation.

Second, there is reason to think that these media are siphoning part of the mainstream media audience for themselves. The Pew Center’s studies show that the overall audience for print and TV news media is shrinking in the US. It’s a pretty safe bet that media like Inside Climate News are capturing viewers who find mainstream coverage of such issues inadequate.

Perhaps most importantly, these upstarts are changing the way that mainstream media cover stories. Because stakeholder-controlled media want to affect future events, they propose solutions to the problems they cover. Solutions are, in another word, hope—and people everywhere desperately need hope that they can believe in. Some news industry executives have recognised in recent years that “positive news” or “solution journalism” are legitimate enterprises. I would argue that any news organisation that wants to grow has to invest in that capacity, and also partner with someone who already has it.

How could Al-Jazeera – or for that matter, any news organisation – profit from these trends, beyond using social media or stakeholder-controlled media as information sources? First, we need to recognise that the trends express a global demand for news media that don’t just report the word, but help to make it better. We can still be objective in one crucial way: We can take all the facts into account whether we like them or not. That will require more investment in investigative skills for reporters, but it will also create a competitive advantage over propaganda outlets like Russia Today.

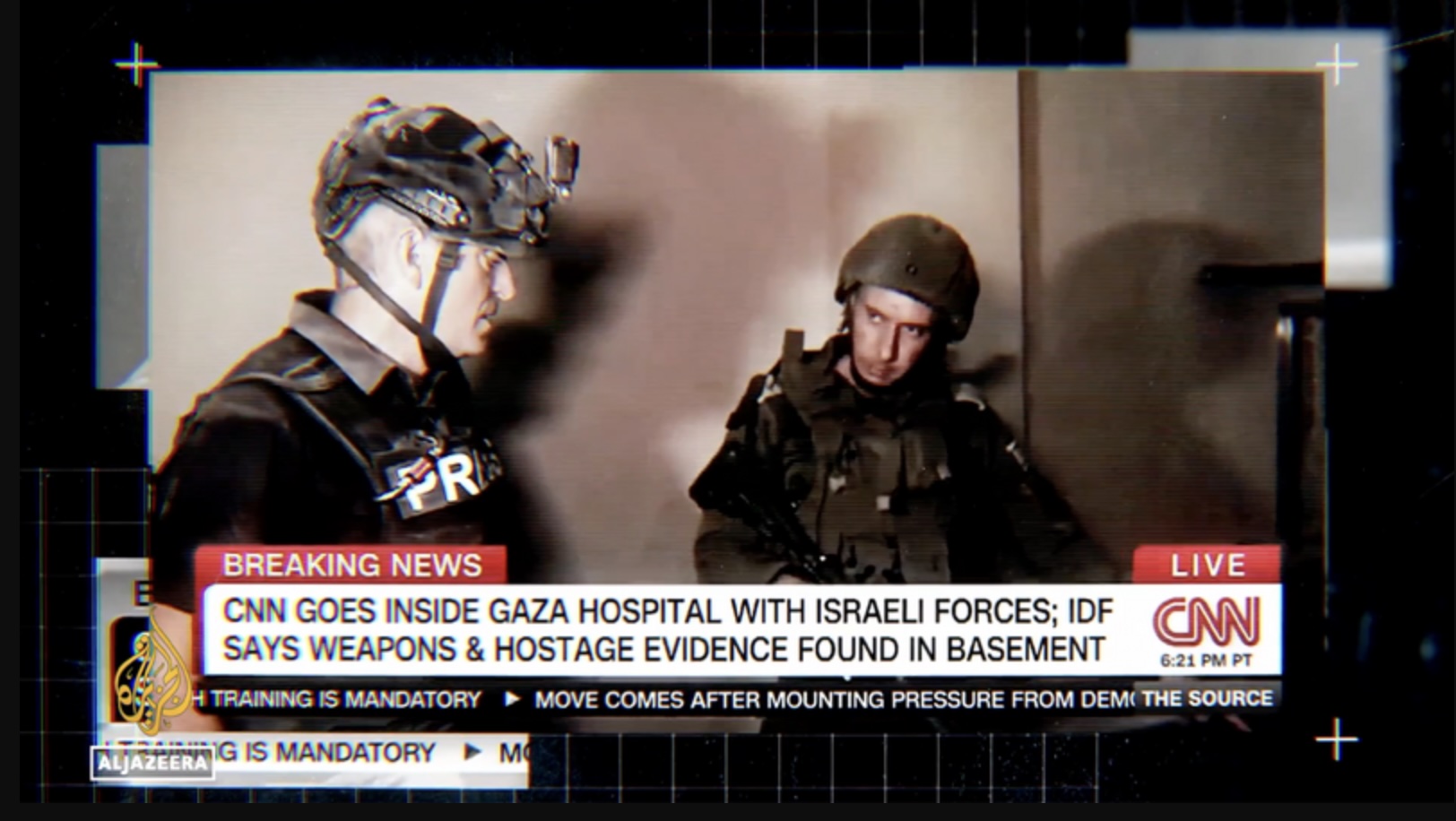

Next, we need to innovate in our relationships with stakeholder-controlled media, because those media have cutting-edge capabilities that most news organisations lack. CNN has attempted this with its Freedom Project, which relies heavily on NGOs engaged in the fight against human trafficking. But CNN gives the impression that the network discovered the subject on its own, and is leading the fight. That’s not a perfect model.

We recently proposed something to the BBC that could work for Al-Jazeera, too: Instead of simply quoting stakeholder newsmakers, or letting them do whatever they like, the network could create a branded avenue where stakeholder news boutiques propose different kinds of quality information.

In opening that street, Al-Jazeera could set rules that serve the public interest: “No self-promotion at the expense of truth or equity. Prove what you say, and don’t leave out facts just because you don’t like them. Tell us why you’re giving us this story. If someone gave you money to do it, or simply to exist, tell us who. If you can’t be objective, you’d better be fully transparent.” In other words, stakeholder groups who meet high standards could become branded partners of a great news organisation.

One way or another, the future of news organisations will depend on building resources to make their viewers’ lives better. Most news organisations haven’t accepted that responsibility, or are simply pretending to themselves that they have. Viewers aren’t fooled; they know what they need. We can give it to them and still be true to our craft and our mission.