In part two of our series on how the media can propagate hate speech, we look at ways that journalists can ensure their work is balanced and objective, to avoid this.

When dealing with controversial topics, discrimination and incitement to hatred can only be avoided if journalists are careful to maintain professionalism and keep to the rules of ethical coverage. As long as they do this, journalists can be safe in the knowledge that their coverage will not cause any harm.

“It is obvious to anyone familiar with Libyan media that outlets are biased in favour of particular parties to the conflict,” says Libyan journalist Ismail Al Giritli. “They rely on sources from their preferred party, and use language glorifying one side and demonising the other. The same applies to the lists of guests and analysts interviewed, the adverts and commercials broadcast during the breaks, the titles of news pieces, the questions asked, the issues presented and the topics discussed on discussion programmes.

Read more

Part One - How the media can promote hate speech

Opinion - The media must stop obsessing about 'economic migrants'

“And the correspondents of a given media outlet always operate in the areas controlled by the group their employers support. Bias also appears in how mental images are drawn for the public. Outlets neglect to define the warring parties and their geographical, ideological and political affiliations, and use images and background music promoting not just bias but broader social division. Many journalists and media officials show their bias for specific parties and use the space provided to them by social media to openly declare these biases.”

Lies and statistics

A good example of bias in the media was when a local girl was murdered in Spain by Moroccan immigrants. Ayman Al Zubeir, Madrid Correspondent for Al Jazeera, explains: “The Spanish far right was quick to exploit the crime to incite the population against the Moroccan community, using incorrect information in order to influence the electorate. One of the lies circulated by the right was a story that 70 percent of those detained in sexual harassment cases have foreign citizenship.”

But statistics from official Spanish bodies like the Instituto Nacional de Estadistica and the General Council of the Judiciary actually show the opposite. In 2017, Spanish courts handed down prison terms to 2,280 people accused of sexual assault, whose nationalities break down as follows: 1,705 were Spanish; 184 were from the Americas; 167 were from the EU; 137 from Africa; 58 from Asia; and 27 were from Eastern Europe.

“These numbers show that 70 percent of these crimes are committed by Spanish citizens,” says Al Zubeir. “But, despite this data, more attention is given in some media outlets to crimes committed by Moroccan immigrants. This can lead to incidents of racist violence, as in some towns in Catalonia, where refuge centers for underage migrants have been attacked.”

So how can journalists ensure they report the facts in a balanced way, which does not lead to more mis-placed resentment against migrants and refugees?

Step 1: Story planning

Building up a base of knowledge about the incident

Before working out sources and writing a news story, a journalist should carry out thorough research into the issue he or she will be working on and gather all available information from specialised sources (reports, statistics, academic studies etc).

The following are some major platforms that provide journalists with reports and studies on the topics of their stories:

Google Scholar: A search engine from Google that specialises in academic studies, making it possible to access various studies published in peer-reviewed journals as well as reports giving journalists a deeper understanding of the stories they work on.

Microsoft Academic: A similar platform to Google Scholar containing approximately 227 thousand research papers as well as an academic CV search feature, helping journalists to identify expert sources.

UN databases: This database includes all reports issued by the UN and its legal and human rights arms as well as all treaties, agreements and statistics released by the UN itself and by member states.

The Verification Handbook: Published by the European Journalism Center (EJC), this handbook provides tools and techniques allowing journalists to search the internet more broadly and helping them verify reports & information.

Selecting sources

Look at all sides of the story and select people or organisations that have been affected. For example, in a story about the effect of refugees on job opportunities in a particular country, concerned parties include: refugees, local authorities, unions and workers’ associations, local residents, employers, and economic experts. The absence of any of these parties means the story will not be objective and will be biased towards one side’s narrative over the other, meaning the story is more likely to constitute bias.

This story headline attributing high rental prices to Syrian refugees published in the Jordanian newspaper, Al Ghad, used the narrative of one side of the story (property owners) as its main source without presenting the opinions of any other relevant parties, such as Syrian refugees themselves or economic experts. This means it takes a particular direction in its reporting.

The most important sources that a journalist should refer to when putting together a story are:

- Parties directly affected by and affecting the story (citizens, refugees, workers, property-owners, traders etc).

- Official bodies relevant to the story (mayors, relevant government ministries, etc). The story has to be within their jurisdiction.

- Experts (experts are expected to give methodical evaluations without personal opinions).

- NGOs or semi-governmental organisations (unions, civil society organisations, rights organisations etc).

- Raw data (reports, studies, statistics).

- User-generated content.

Verifying information

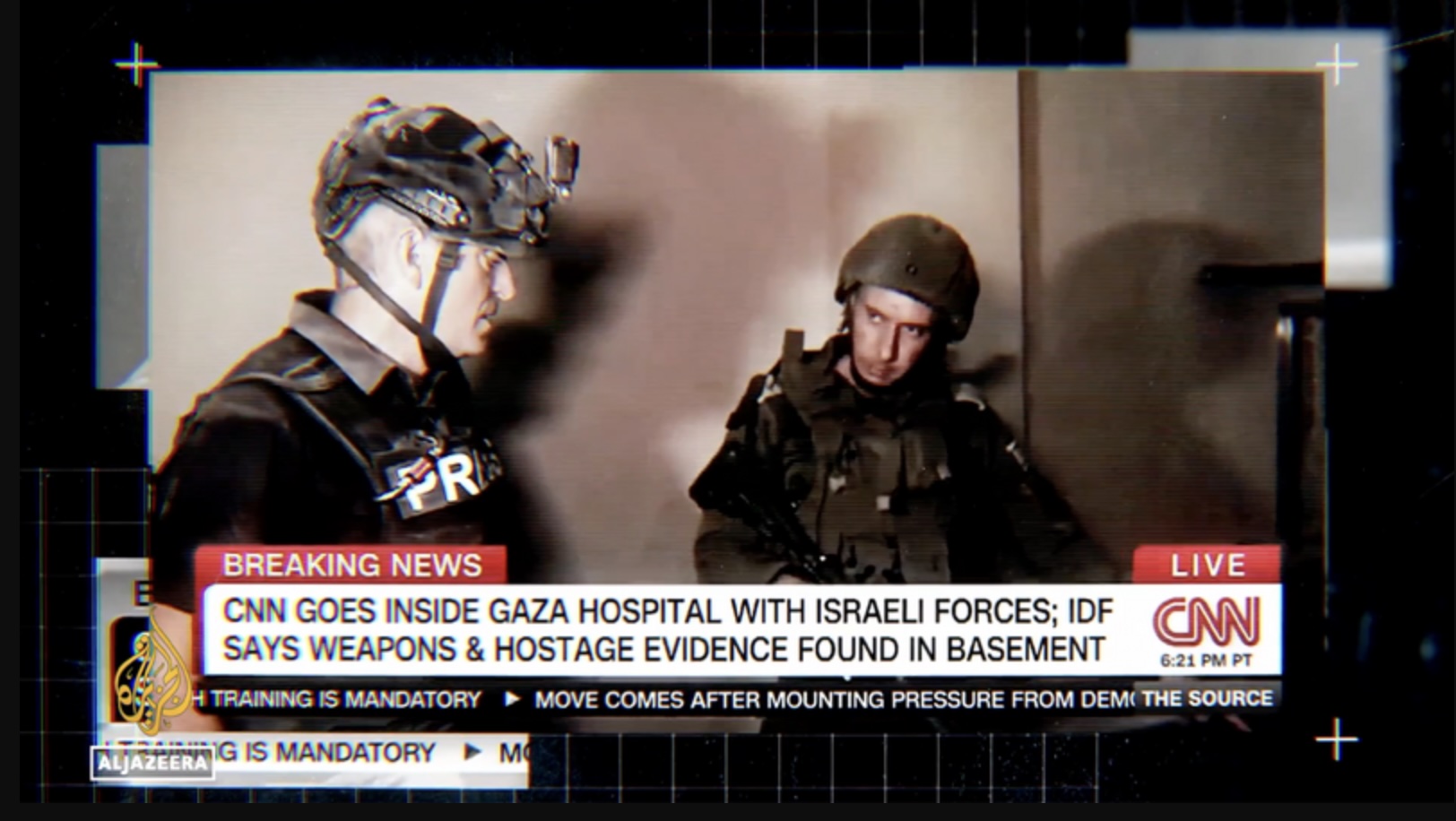

Some sources may give mistaken or inflammatory information. Journalists should not publish this information as fact without verification, even if they state its source clearly in the story.

Professionalism requires us to cross-reference it with other sources and present all of the information together in the story. This will encourage the public to question how accurate the information provided by a particular source is and compare it with other sources appearing in the story.

Open-source content

The vast quantities of content made available on social media sites (“user-generated content”) are an important source of information that journalists can use in parallel with traditional sources. But despite its importance, open-source content can be fabricated and used to promote lies and rumours that may constitute hate speech.

Journalists who use information from social media have to verify and fact-check this information. We have already mentioned a few relevant sources: the News Verification Guidebook, Finding the Truth Amongst the Fakes, and the EJC’s Verification Handbook.

The Ethical Journalism Network (EJN) suggests that journalists always ask themselves the following questions when dealing with information taken from social media:

- Have I corroborated the origin including location, date and time of images and content that I am using?

- Have I confirmed that this material is the original piece of content (ie not modified or abridged)?

- Have I verified the social media profiles to avoid use of fake information?

- Is the account holder known, and has it been a reliable source in the past?

- Have I asked direct questions of the content provider to verify the provenance of the information?

- Are there similar posts or content elsewhere online?

For example, a clip from a video of a Friday sermon given at a Saudi mosque in January 2014, in which the speaker asks non-Saudis not to attend prayers, was shared widely on social media. The clip implied that the preacher was discriminating against non-Saudis. In this case, journalists should have watched the whole video, which shows that the clip was taken out of context and that the preacher was in fact criticising racism by acting out an example.

Important questions to ask yourself

- Why should I cover this story? Summarise each reason then evaluate it according to its importance to the public as compared to other stories you could cover.

- How is this story expected to benefit the public?

- What aspects of the story are absent from the media? Try to find a new approach to the story.

- What is the worst way the story could possibly be produced? Think of an unprofessional and unobjective way the story could be approached. Why would it be unprofessional and unobjective? Analyse in order to avoid.

- What is the ideal way to cover the story? Think about the best form the story could possibly take, even if it would be difficult for you to achieve in reality because of limitations. Try to come as close to it as possible.

- What are the sources I should use to achieve balance in the story?

- Have I conducted enough research and informed myself sufficiently about the various aspects of the story, allowing me to understand all of its different dimensions?

- Have I considered the sources’ individual circumstances and peculiarities? Try to understand their circumstances in order to ask them appropriate questions while respecting the specific nature of every case.

See our guidebook on covering refugee stories.

Step 2: Producing the story

Always make sure you ask questions appropriate to each source or side. When interviewing or following up authoritative personal accounts that may have a real influence, think about whether these statements constitute incitement or discrimination or encourage hatred or violence.

Only use them if there is a clear editorial justification, and make sure you contextualise them and include responses from other affected parties. Do not produce your piece from behind a desk. Go down to the scene of the events to see what is going on for yourself. Do not rely only on your sources’ accounts.

Look at existing news pieces on the topic you want to write about. Work out what aspects of the story have been ignored or given incomplete or unprofessional coverage, and try to draw them out in your own story. Make sure to evaluate content, whether statements, pictures or video clips. Think about the possible consequences of using it. Make sure that you understand the local society and the cultural, social and religious context.

Important questions to ask yourself

- Have I informed sources of the nature of the story? Have they given their consent to be quoted or to appear?

- Have I been balanced in the sources that I have chosen? Have I given them the right to comment on information concerning them?

- Were the questions I prepared appropriate to the topic? If the answer is “no”, then come up with more relevant questions and return to the sources.

- Did I obtain the information in the story from a range of different sources? Some sources may give you incorrect information or figures in order to serve a particular agenda. Try and cross-reference information as much as possible.

Step 3: Writing the story

Having completed steps one and two and started writing your story, you should arrange the different narratives by importance, ensuring an equal distribution of opinions. In some cases the opinion of one party will be based on inaccurate information, and may constitute a kind of incitement against a particular individual or group. Here it is the journalist’s role to respond to these inaccuracies by providing correct information.

Advice for writing an objective story

- Avoid generalisations and language implying value judgements or stereotyping communities or individuals.

- Do not treat information given in official or unofficial reports as unquestioned fact (for journalists, any report should simply be one source among many)

- Do not draw personal conclusions in your story.

- Put your expectations to one side, and avoid stereotypes and prejudices.

- Make sure you use objective and value-free language.

- Provide minorities with a voice equal to that of the majority.

Balance information gathered from sources and divide it across the themes of the story without giving one side a louder voice. Some media outlets adopt the perspective of one party, provide no space for those with dissenting opinions to lay out their own position and do not consult experts in order to verify the information given by sources.

Make sure that the information attributed to different sources lines up with what they have said. Put quotation marks around any expressions that express a value judgement.

Assess the sensitivity of pictures and information appearing in the story. Make sure they do not contradict professional standards or infringe on the rights of particular individuals or groups.

Meet with editors to evaluate your story if you feel that there might be an ethical dilemma in its current form, or if it contains information that may be sensitive for some members of the public.

Important questions to ask yourself

- Have I formulated the story objectively? Have I presented different sources’ narratives faithfully?

- Have I put quotation marks around expressions that express a value judgment and attributed them to the source?

- Have I given all sources’ statements similar weight in the story and provided important information from all sides?

- Have I assessed the statements appearing in the story and the risks associated with publishing them?

- Have I used language that may be harmful to a particular community or described them negatively?

- Have I avoided any unobjective conclusions or value judgments concerning the story?

- Have I excluded my personal opinions from the story and distanced myself equally from all parties?

- Have I made sure not to include any information that might harm sources or the public? In cases where journalists face the ethical dilemma of deciding which is more important, the publication of the information or the risks associated with it, go back to one of the ethical evaluation models given above.

- Have I only included important information in my story? Not everything sources say is actually important. Make sure you only include information relevant to the story and its context.

- Have I only included information that sources have given me permission to use in the story?

- Have I protected the anonymity of sources who have asked me to do so?

Step four: Ethical evaluation of the story

Sticking to the principles of objective journalism is not enough to ensure that a journalist does not accidentally engage in discrimination in a story. He or she has ethical responsibilities that must be carefully considered before deciding to publish.

Journalists often produce stories that seem to conform generally to the rules of journalistic professionalism and objectivity but whose general orientation helps to reinforce speech promoting discrimination or hatred. This might be because of the nature of the sources chosen or the language used, or because of other decisions that give one side a louder voice than others.

Journalists may reinforce speech promoting discrimination or hatred without meaning to or without realising the consequences of this speech and its effects on the reader.

A group of European journalists’ associations in Europe called The Ethical Journalism Initiative has made a number of general recommendations relevant to this topic.

These recommendations are summarised in a list of questions that journalists can ask themselves to help ensure diversity in their stories:

- What are my own personal assumptions about the people I am reporting on?

- Am I open to accepting ideas for stories that go beyond my own cultural standpoint?

- Have I any prejudicial attitude to the issue that might negatively affect the subject of the story?

- Are any references to colour, race, or physical appearance in the story relevant to the topic?

- Have I used correct terminology to describe individuals and their culture?

- Have I discussed the topic with experienced colleagues familiar with the subject?

- Have I used different opinions and sources in the story, including those of minorities?

- Does the story simply follow prevailing attitudes? Have I questioned these attitudes?

- Have I made sure that the story does not reflect stereotypes?

- Have I directly considered the needs of those involved in the story?

- Have I taken into account the effect of the story or the images used on the lives of others?

Models for ethical evaluation

There are various different models that can help journalists to make ethical decisions using moral reasoning. Journalists can apply these models to news stories in order to make sure that they are both ethical and professional:

The SAD formula (situational definition, analysis, decision)

This model can be subdivided into three stages:

Situational definition

- Describe the facts appearing in the story.

- Establish the conflicting values and principles in the story – for example, conflicting figures for the same topic or conflicting values.

- Try to formulate a single ethical question that sums up the ethical dilemma presented by the story.

Analysis

- Try to create a discussion with your colleagues concerning the conflicting facts and values within the story.

- Take account of external factors that might affect the story.

- Look at what your organisation normally does in similar cases or make use of similar experiences.

- Establish the parties affected by this ethical decision (you, your colleagues, your sources, society, etc).

- Take into consideration your own emotional attitude to the decision as opposed to your rational attitude.

Decision

- Make a final decision.

- Justify that decision logically in response to possible criticisms.

The Dilemma Method

This model is based on the creation of a dialogue within the newsroom. A journalist dealing with an ethical dilemma concerning an aspect of a story works with his or her colleagues to produce a consensus decision:

- Introduction: A general introduction is given to familiarise the journalists with the ethical sensitivity of the story and demonstrate the importance of the decision they are going to make.

- Presenting the issue: The journalist presents the facts that he or she has collected (facts only, with no influence from his or her opinion).

- Formulating the ethical question and defining the dilemma: The ethical question that the journalist who has prepared the story wants colleagues to help him or her to answer is laid out in the following form: “Should I [first suggestion], [second suggestion] or [third suggestion]…?”

- Brainstorming: The journalists ask questions about the story and its different aspects and then discuss some general questions, citing previous experiences and similar stories.

- Analysing the dilemma: We begin to analyse the dilemma by comparing it with professional and societal values, the possible response on publication and the parties that may be harmed by each suggestion.

- Beginning to search for alternatives: Here the journalist asks colleagues to think about alternatives to the suggestions he or she initially presented.

- Individual decisions by each journalist: Colleagues submit their individual decisions using pen and paper by answering as follows: a) I believe that the best decision is to (one of the suggestions), because (giving a professional justification of the decision). b) Although this choice may lead to (the potential negative effects), c) this can be avoided by… d) And so (the decision he or she has chosen) is the ethical option that should be taken, given… (professional justifications).

- Opening up discussion: The answers are then collected and colleagues discuss them, with the aim of expanding discussion points in order to look at all aspects of the dilemma and weigh them up against one another in order to reach a consensus decision.

- Summarising conclusions: At the end of the discussion, the team takes a single ethical decision by majority vote.

- Assessing the dilemma: After an ethical decision is made and the story is published in a particular form, the effects of the decision are assessed (positives and negatives) in order to benefit from the experience.

Important questions to ask yourself

- If you can’t answer a question decisively, go back to the ethical evaluation methods.

- What are the possible risks associated with publishing the story? What are the possible benefits?

- Do I have sufficient professional justification to publish the story? Can I avoid any possible risk?

- Was serving the public interest my only criterion in assessing the story? If not, what were my other criteria, and did this affect the balance of the story?

- What is the worst that could happen if this story is published? What is the best that could happen? List the possible negative and then the possible positive outcomes of publishing the story. Try and find ways to forestall the negatives as much as possible.

- Will this story lead the target demographic to feel hatred towards a person or group on the basis of their identity?

- Will the general context in which the story or the headline is being published lead to the creation of an atmosphere of hatred or discrimination towards a given person or group of people on the basis of their identity?

- Does the story stereotype or misrepresent a person or group based on their identity

An earlier version of this article first appeared in the AJMI publication, Avoiding Discrimination and Hate Speech in Media