The world is full of fake news, nowhere more so than when it comes to scientific issues, so science journalists must develop a keen sense of scepticism. We look at why it’s so important to keep a clear head and search out the facts.

In 2019, the website altmetric identified a paper written by four computer scientists as the most-discussed academic work of that year worldwide.

This paper described how deepfake AI had been able to produce a video clip from a single still.

Read more: How to do science journalism - and do it right

But the title: “Few-Shot Adversarial Learning of Realistic Neural Talking Head Models”, is practically incomprehensible to the average reader – never mind the content. The authors, writing for an expert audience, used a slew of opaque technical terms.

Nonetheless, this paper, recast into more appropriate language, received widespread newspaper coverage.

Audiences were drawn in by eye-catching headlines like “The Mona Lisa was brought to life in vivid detail by deepfake AI researchers at Samsung” and “Samsung deepfake AI could fabricate a video of you from a single profile pic.”

As an audience, we are interested less in the achievements of researchers than we are in how they can be used.

Deepfake technology is obviously attractive to security and intelligence agencies, and human beings more broadly tend to be quite willing to break the law when they know they can get away with it.

In the age of fake news, it would be no surprise if a widely circulated video of a world figure caught in a compromising position turned out to be a fabrication. In fact, it has now been proven that technology can produce convincing clips of people saying things that they have never said.

Innovations of this kind are of more than just scientific or ivory-tower relevance. They have direct effects on our daily lives. You have probably seen the fabricated video of Mark Zuckerberg talking candidly about his power and influence as the owner of Facebook.

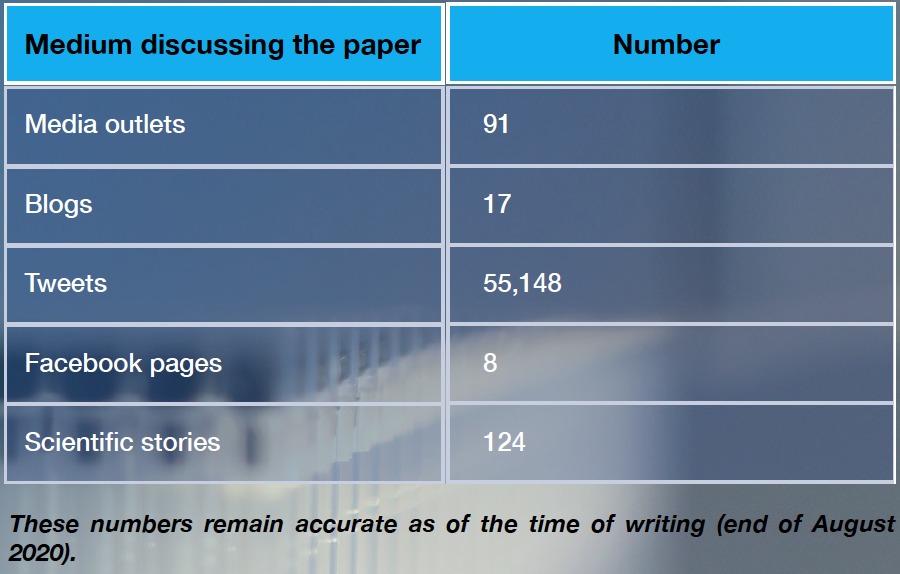

The table below shows media circulation of the deepfake paper. It only includes science journalism, not traditional news stories.

So at a time when the ‘evidence’ can be fabricated to such an extent, how can we tell whether something has been faked - indeed, how can we tell the conspiracy theories from the truth?

Let’s consider two important cases of our time - COVID-19 and the development of 5G internet technology.

It was called 'a biological weapon' - COVID-19

There has been a huge amount of coverage on COVID-19 in both the Arab World and elsewhere, with a concurrent marked spike in fake and misleading news.

A study published on March 19, 2020, by the Center for Informed Democracy and Social-cybersecurity (IDeaS) at Carnegie Mellon University estimates that some 60 percent of US Twitter accounts discussing the coronavirus were, in fact, bots set up the previous February in order to disseminate fake content promoting conspiracy theories and the reopening of US society.

These accounts targeted groups influential in public opinion formation – activists, minorities, and immigrants – by boosting dozens of misleading stories spread by 82 percent of real accounts. One of the main stories in this disinformation campaign focused on a theory that the virus was a biological weapon developed by hostile countries.

The problem is not limited to the public, however. Government institutions are also important media sources. One of these institutions is the National Center for Medical Intelligence, which is responsible for the health of US military forces at home and abroad.

From the first weeks of the pandemic, US newspapers and news agencies have relied on this organisation as a trusted source, alongside the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The remarkable influence of US policy and national interests on what is published by these agencies is obvious, particularly given that most local media rely on US media to one extent or another in their coverage of international affairs.

If the sort of fake news explosion we have seen recently is what is happening in the most powerful country in the world, what sort of chance do the rest of us have?

The coronavirus pandemic is a scientific issue with great political, security, and economic ramifications, an issue in which fake news is a natural, predictable, even dominant phenomenon.

The only way to address this phenomenon is to make sure the public is better informed. And the way to do this is through good science journalism.

There is another factor of great importance to coronavirus news-making. Traditional journalists are exposed on a daily basis to vast quantities of often negative news, but do not notice how this affects their own behaviour and mindset.

This psychological effect naturally has implications for their work, for their choice of topics, and for the way they approach these topics.

Emotional responses produce hasty or incomplete judgements or emotive language that says more about the writer’s state of mind than about reality.

There has been a distinct uptick in intemperate headlines since the pandemic began. This problem can be solved, once again, by clear-headed journalists not obsessed with scoops and free from the influence of editorial policies often directly driven by politics.

The importance of bold, objective and rigorous press coverage here is clear. And herein lies the importance of science journalism.

'A vast conspiracy' - 5G Internet

Warnings about the supposed dangers of 5G networks had already spread like wildfire on social media and in traditional media worldwide when the coronavirus pandemic began and this development only fed the theory that these networks are part of a vast conspiracy.

In late 2019, AFP published a report on the health risks associated with the new technology.

You might expect that a piece from one of the oldest news agencies in the world would give you a clear and scientific answer to this sort of question, but this report would have disappointed you.

Its closing lines told us that the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety was set to conduct a study on the effects of 5G, which were to be completed by the end of 2020.

And, although this report was published on the section of AFP’s website dedicated to fighting fake news and concerns a purely scientific topic, no clear answer was given to the question: How dangerous is 5G internet to human health?

Arab and international news are replete with pieces on 5G internet and the fierce international competition for control of the new network infrastructure. But objective, scientific reporting is very thin on the ground.

A Google search, for example, gives us 3,840,000 results relating to 5G internet and its political impact, but only 436,000 on its health risks - and tens of thousands of the pieces in the latter category cannot be counted as science journalism in any sense.

Activating a 5G network requires transmitters (transmission towers) to be set up in order to broadcast the high-frequency waves that carry the data. In all the countries that choose to adopt the new technology, transmitters will have to be put up in residential areas in order to provide the service.

These transmitters are 1.2m tall and operate constantly at high frequencies. In 2017, 171 scientists from 36 different countries signed a petition warning of the possible negative effects of 5G on human health. This was based on an earlier petition, submitted to the UN by 220 scientists, which called for a range of measures to be taken to protect humans from the risks of “unsafe electromagnetic fields,” by which they meant the 5G frequency.

This petition stated that: “Numerous recent scientific publications have shown that EMF affects living organisms at levels well below most international and national guidelines.

“Effects include increased cancer risk, cellular stress, increase in harmful free radicals, genetic damages, structural and functional changes of the reproductive system, learning and memory deficits, neurological disorders, and negative impacts on general well-being in humans.

“Damage goes well beyond the human race, as there is growing evidence of harmful effects to both plant and animal life.”

Is this enough to form a solid conclusion on the health risks of 5G? What has changed since it was first published? How did these scientists reach their conclusions? Who funded the studies that confirm or deny the existence of health risks? Are there measures that can be taken to counteract any possible dangers to human health?

These are just some of the many questions someone interested in a scientific issue has to ask – and yet more evidence of the importance of specialised science journalism.

A version of this article appeared in the Al Jazeera Media Institute's publication, the Science Journalism Handbook