Hungary was one of the first Soviet-controlled countries to welcome refugees in the late 1980s. These days its government is one of the most opposed to migration in Europe. We examine how the media paved the way for this turnaround

“This barbaric herd, which should be eliminated, raped women in Milan again. Will they stay in Europe, what do you guys think?” Mused Zsolt Bayer, a right wing commentator, and one of the founding members of Fidesz, about the fate of migrants, as he turned to one of his guests attending his roundtable Sajtoklub, a show offering commentary that appears on Hir TV, a government-friendly cable news channel in Hungary.

“You bet they will,” smirked his guest to a chuckling Bayer, who has received one of the highest orders of merit granted by the ruling party despite calling migrants “animals”, “uncivilised”, “Jews stinking of excrement”, and even labelling the pope a “demented old geezer, or a villain” for condemning Hungary’s treatment of refugees.

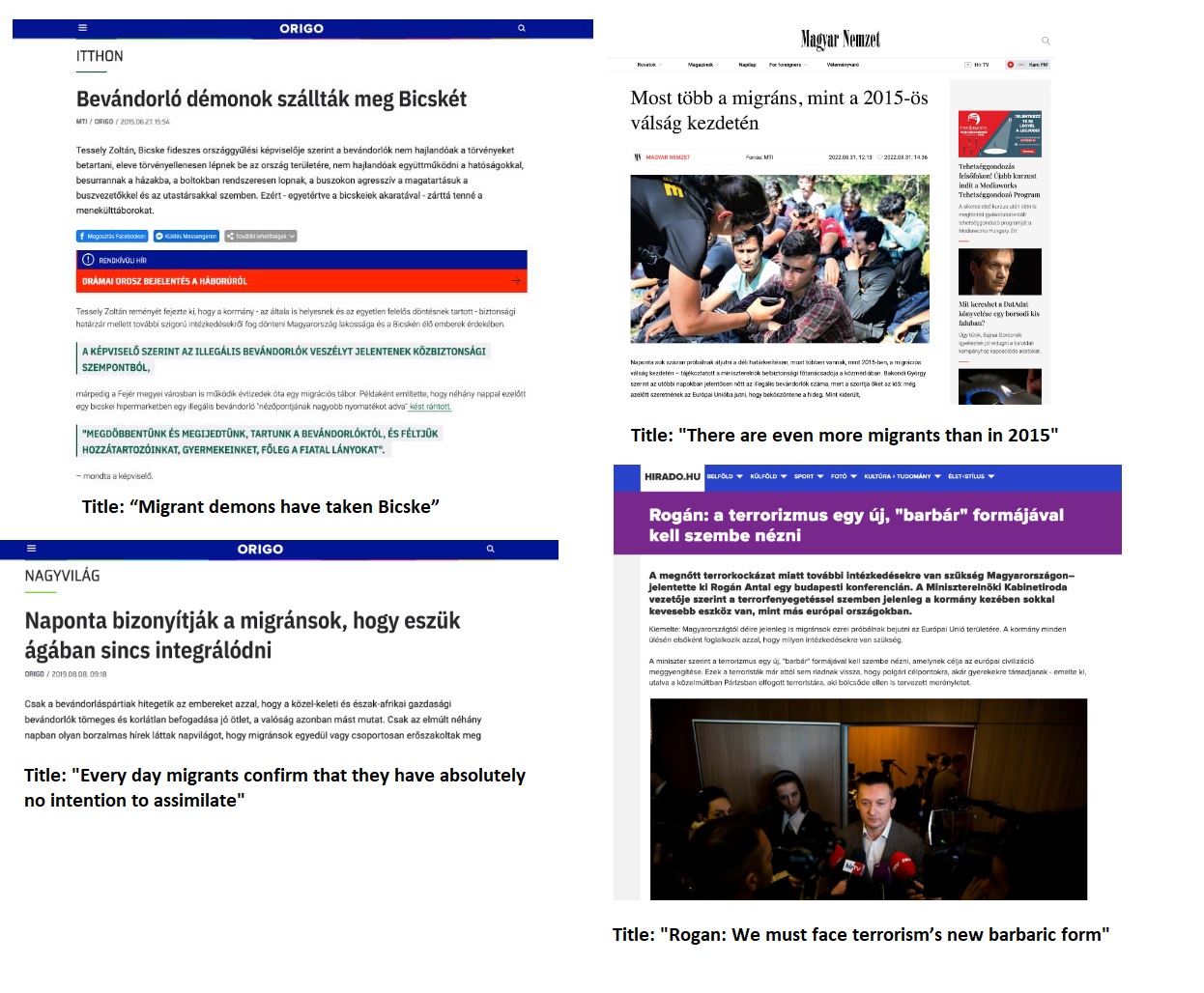

“Statements regarding refugees that would have shocked the nation now seem common and hardly cause an uproar,” says Szabolcs Panyi, who is an investigative journalist at the independent digital site, Direkt36.hu. “Hungarian politics have moved to the far right over the years and the media, strategically harnessed by the government, have followed suit.”

Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orban and his Fidesz-led government - in power for 12 consecutive years with four more to come and a two-thirds majority in Parliament since 2010 - have worked hard over the years to control the media. By autumn of 2018, they had founded KESMA (the Central European Press and Media Foundation, Közép-Európai Sajtó és Média Alapítvány), the government-friendly media conglomerate that has absorbed more than 500 regional and national outlets which, along with taxpayer-funded national TV and radio and other non-KESMA but government-affiliated independent outlets, hands the authorities a more-than 80 percent monopoly over the nation’s news stream.

“These media outlets get a daily wire from the powers-that-be about the most essential talking points that they are expected to regurgitate,” says Panyi who has expressed concern about the most recent changes in the ruling party’s top positions: The “propaganda minister”, Antal Rogan, who approves the state-friendly media’s daily talking points, now also oversees the secret service. “The alternative reality stream effectively shapes the nation’s consciousness, while the room left for independent journalism to fact-check and contest misleading statements is shrinking.”

Avoiding 'another Simicska'

KESMA is overseen by Mediaworks - one of its largest media acquisitions - which previously belonged to businessman Lorinc Meszaros, Orban’s childhood friend and a former pipe fitter who has become one of the wealthiest men in Hungary. Over the past year, the pro-government conglomerate has received about one hundred billion HUFs (around $35 million). Besides the news, it engages in various services such as advertising, ticket and property sales via its websites and has bypassed Hungary’s competition act as it is identified as a “special national economic project” that “serves the public good”.

“With KESMA, the government wanted to make sure that the Simicska-style story does not happen again,” says director of the independent news outlet, 444.hu, Peter Erdelyi about one of the oldest and most faithful allies of Orban, the co-founder and the “business mind” of Fidesz, Lajos Simicska, who publicly fell out with the prime minister and then instructed media outlets under his oversight to criticise the authorities. “With KESMA it meant that in the event of a feud with another owner of a government-friendly paper or TV, Orban’s messaging regarding sensitive topics such as migration, would remain on track.”

Experts now fear that the government’s latest levy on advertising revenue will suffocate the remaining strongholds of independent media that benefit from ads on their platforms.

“Some of these liberal cable companies like RTL Klub are in German hands,” says Panyi who has been targeted by the controversial Israeli spyware, Pegasus - a software which contaminates electronic devices and was initially designed to catch criminals and terrorists. “Independent outlets counter the propaganda, discuss the misleading campaigns against migration, or whatever the authorities are identifying as evil, but if they fall short of revenue, they would likely be sold by their owners to bidders ready to serve government interests.”

‘Curating reality’

Bernadett Szel, a former MP, says that Orban made it clear in the 1990s that whoever controlled the media would have command over the country. However, she says, the pressing need to “curate reality” emerged with the 2015 Syrian migration crisis.

“The sympathetic voices needed to be rooted out,” Szel says. “They knew that migration was a topic around which they could rally supporters, so they masterfully twisted reality with the help of the media.”

She remembers that in 2015 - like now, with the Ukrainian crisis unfolding next door - Hungarian volunteers and people were helpful and enthusiastic about providing assistance to refugees stuck at the train stations in Budapest. Thus, at first, it was a long shot for the authorities to ignite anti-immigrant sentiment across the nation. The government, in her opinion, ignored the needs of thousands of migrants to sow chaos in public spaces, since people in desperation were more likely to cause havoc.

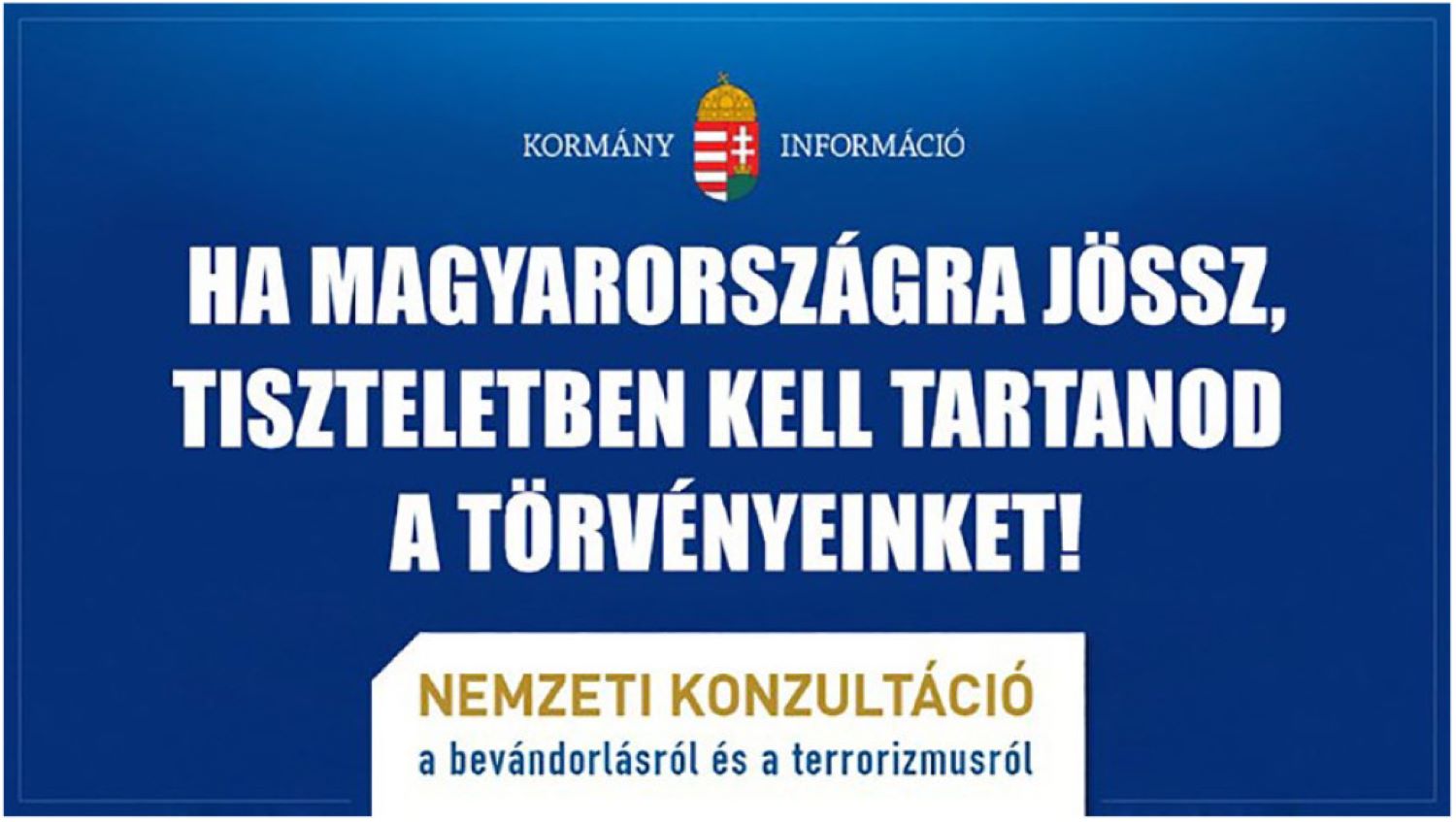

“Then the government installed these propaganda banners everywhere which read in Hungarian that ‘if you come to Hungary you must learn our language’,” says Szel, stressing that these messages were not for the refugees who spoke no Hungarian but to inflame fellow citizens about the “intruders”. “Families, women and children were all visible, so the authorities’ disinformation campaign was not hitting home, just yet.”

Leaked state media documents also revealed that later, taxpayer-funded state TV channels were forbidden from showing images of refugee women and children.

In a 2021 documentary, titled Five Lessons about Doing away with Reality a former state television employee, Krisztina Balogh also said that the news she had to produce often communicated made-up content about migrants, and on one occasion she had to find a doctor for her broadcast segment to corroborate the false statement that migrants carried diseases.

“I could not find anyone here in Budapest,” she said. “But the editorial team identified an individual in the countryside who was willing to repeat word-to-word what my editor wanted to have in the report.”

‘Painting an apocalypse’

Szel says that the government had it easier with its fear mongering propaganda once, in the fall of 2015, the highly controversial fence was installed along the country’s southern border first between Hungary and Serbia, then between Hungary and Croatia.

“Then there was the EU’s quota system for member states to accept a number of Syrian refugees,” says Szel about the 2015 ruling which would have meant that Hungary admit about two thousand people over a period of two years, but the government vehemently opposed the ruling and even organised a referendum, which albeit invalid served as a catalyst for the authorities’ anti-migrant laws.

“In fact hardly any refugees wanted to stay here,” Szel says. “But this did not matter, as the authorities painted the migrant influx in apocalyptic terms.”

By the end of 2015 there were nearly 400,000 Syrian refugees who crossed into Hungary - a country of 10 million - out of whom 177,135 were registered for asylum, but only a handful - a bit over 500 - obtained their papers as most of the petitioners did not qualify. Many waited for the issuance of these documents and moved on to Germany, Austria and wealthier Scandinavian nations. Despite the low number of refugees intending to stay, the crisis presented an opportunity for the authorities to posit the non-European “other” as an existential threat against whom they could unite the nation, tighten asylum laws and justify their need to hold onto the reins of power.

“To a rural person who has never seen anybody who looked different and had a different religion, the migrant person embodied all their imaginary fears,” says Erdelyi. “With this in mind the authorities deployed tactics to incite fear across the nation with the help of their media, no pun intended, but such moves would be unimaginable with people who are our neighbours and look like us, and have similar cultural and historical heritage.”

Over the past few years, government-friendly TV and radio has served up commentary that highlights that migrants are dangerous. The narrative is that they want to come here to “reproduce” and “replace locals”, and take advantage of Hungary’s economic safety. One far-right commentator, Zsolt Tyirityan even said that migrants were so uncivilised that they did not even know how to use toilet paper.

Demonising migrants

“Stereotyping comments give leeway to unnecessary paranoia and violence,” says Erdelyi. “There were many incidents over the years that indicate the escalation of this trend.”

When a lady went to her local hairdresser, and put on a scarf upon leaving the salon - to protect her freshly coiffed hair from a light drizzle - a village resident alerted the police that “there was a migrant” on the loose.

Then there was another incident when three Sri-Lankan college students, who were just about a day in Hungary decided to volunteer at a hospice, again only to be detained by the police as locals reported them.

Perhaps one of the most well-known cases involves a man who offered Migration Aid help with accommodating a few refugee families at his holiday let, but his village neighbours got so worked up over his plans that they threatened him and punctured his car tires as a warning, which ultimately culminated in the man withdrawing his offer.

As Russian missiles obliterate much of Ukraine’s infrastructure next door, Hungary’s state-funded media have commented on the difference between the Middle-Eastern “migrant” banging on the southern border and the Ukrainian “refugee”. Accordingly, the former individual wants to come to Hungary to cause trouble while the latter is seen as a genuinely wronged person, fleeing the atrocities of the war.

Conversely, since Russia attacked Ukraine, Hungarian state media have failed to blame Vladimir Putin, Russia’s leader and Orban’s faithful ally for the unfolding calamities. When Orban was asked by reporters at a press conference to offer an opinion about the Bucha massacre - which involved blindfolded Ukrainian civilians with their hands tied in the back and shot in the head littering the road - the Hungarian prime minister said he didn’t see the images so could not offer a comment. The authorities’ unwillingness to point at Putin’s wrongdoing has sparked the spread of Russian propaganda across government controlled and friendly media as well, with most outlets saying that Zelensky was a clown, war images’ authenticity was dubious, and some commentators like Zsolt Bayer suggesting that the gruesome photos of the war were staged by Ukrainians and the West.

“Orban on one hand boasts that Hungary has aided and welcomed many refugees on the other rubs shoulders with Putin,” says Panyi. “But in essence the refugees are not welcome, the dynamic is not the same as in 2015, but there is animosity building up.”

So far over nearly 2 million refugees have come to Hungary since the war in Ukraine began, and numbers are likely to rise as the fighting continues, though most of those who are displaced and enter the country, like in 2015, almost immediately leave for Western nations.

Now critics say that the Hungarian authorities deliberately inflate the number of Ukrainian refugees staying in Hungary to receive EU funds, but many fear that the money will be spent elsewhere, since Hungary is facing a steep budget deficit, partly due to the EU’s decision to withhold Hungary’s pandemic aid over its asylum policy.

‘Truth is, no refugee wants to stay here’

The controversial Soros package of bills - dubbed after the Hungarian-American financier George Soros - came into force in 2018 following the Syrian migrant crisis and makes it hard for refugees to obtain asylum and prevents them from applying for legal protections if they “flee from countries where their lives are not deemed at risk”, moreover, the bill has a clause that accuses billionaire financier George Soros and affiliated NGOs of “aiding and abetting illegal migration” in Hungary, thus criminalises people or organisations who help illegal refugees claim asylum.

“Truth is, no refugee wants to stay here,” says Panyi. Since the war erupted he has hosted a Ukrainian mother and her son who receive about 80 euros per month in refugee aid. “Since 2015 the government deliberately let the asylum system collapse, there is no structure to welcome, to aid refugees or promote their assimilation.”

Hungary launches a media campaign targeting the EU And Soros on February 22, 2019: A billboard with portraits of Jean-Claude Juncker and Hungarian-born US billionaire George Soros shows a slogan reading: "You too have a right to know what Brussels is preparing" [Laszlo Balogh/Getty images]

Hungary hasn’t always been so anti-immigrant. In March 1989, prior to the fall of the Berlin wall, Hungary was one of the first countries in the USSR-controlled Eastern Block to join the 1951 Geneva Convention and adopt the required legal guidance and international help to provide comprehensive support and shelter to about 20,000 ethnic Hungarians fleeing Ceausescu’s regime and a few years later to give hospitality to many during the Yugoslav wars.

But, by the mid 2000s, the sobering reality of a slower-than-expected move to adopt Western policies along with economic uncertainty brought about a rising animosity toward asylum seekers further exacerbated by the 2008 financial meltdown. Experts say that the watershed moment for the government’s anti-migrant stance came on the heels of the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, when radicalised Muslim freedom fighters attacked a satirical paper’s staff, killing many. Shortly after the unfortunate incident the Syrian refugee crisis hit the European Union.

Peter Horvath*, who works for the government’s migration research institute and wishes to use an alias for fear of reprisals, says that the handling of the migrant crisis was something of a “political stunt” as the government conflated migration with terrorism and crime.

“The opposition forces were too weak in the parliament,” Horvath says. “And the government needed something or someone against whom they could portray themselves as the saviours of national cohesion, so migrants became their focus.”

Horvath is convinced that the government’s treatment and the media coverage of Syrian migrants had nothing to do with their faith.

Szel however disagrees.

“The Christian conservative narrative became suddenly prominent, so migrants were targeted and singled out as the bogeymen,” says Szel. She thinks that what matters is one’s behaviour, not where you are from. “Look at us, we are also diverse, we are also changing as a nation, there are many people with different origins living on my street and we get on very well.”

Szel says the government always needs something or someone to fight against.

“May this be this feared migrants, Soros, Brussels or the LGBTQ community,” she says. “The enemy keeps rotating as per the authorities’ behest.”

Building the ‘enemy’ trope

Orban’s obsession with building his political messaging around an enemy started as early as 2008, when he prepared to run for office for the second time. He sought counsel from the conservative political strategist the late Arthur Finkelstein who had successfully advised many Republican, conservative politicians in the United States including president Richard Nixon.

Finkelstein’s partner, George Birnbaum, said that they had advised Orban to draw on the fact that Hungary had been homogeneous, sealed off from the world because of the Iron Curtain, so most of the population had never met people of colour, or of different religions, which presented an opportunity to exploit.

They reasoned that these differences could potentially be used to heighten a sense of nationalism, and the need for a strong government and a charismatic leader.

A 2006/2007 survey also revealed that there was a growing animosity towards people of different origins as citizens were asked to fill out a questionnaire listing six refugee ethnic groups who came to Hungary, including one bogus one, the “pirez”, to highlight which one they found the most threatening. The results indicated that people felt the most apprehensive about Muslims followed by people with Chinese origin.

As for the enemy trope, in 2010, Orban won his second mandate with a focus on the evil of the previous government, and Western capitalism that had caused the financial meltdown. Four years later, in 2014 Brussels loomed as the corrupting force that wanted to bend Hungary to its will, and in 2015 a new opportunity presented itself in the form of the migrant “other” from Syria - the ultimate “personae non grata” - that in 2018 catapulted Fidesz to yet another parliamentary win.

“This political move to deploy an enemy was already there,” says Erdelyi who says Finkelstein’s strategy wasn’t a radically new idea for Hungarian politics. “It was easy to manipulate rural voters who feared that their way of life was going to be threatened, their jobs taken, what they knew, eliminated. This is what Orban’s team tapped into, even though I think on a personal level, he does not harbour anti-Muslim feelings himself.”

Erdelyi has worked with the investigative group Direkt36 which revealed how Hungary’s dubious residency bond scheme offered permanent residency status to non-European citizens for 250,000-300,000 euros with a five-year maturity date.

After the five years were up, investors received their funds back, and could keep their residency papers. This way, many controversial figures from Russia, Asia or the Middle East could obtain Hungarian citizenship and with it unrestricted access to the rest of the European Union. Some of the most notable figures who took part in this scheme included the Syrian strongman Bashar al Assad’s money man, Atiya Khoury, who has been sanctioned by the United States for human rights violations.

“You see all these friendships and political alliances with the Middle East, Turkey being a good example,” Erdelyi says. “So I would be careful to say that there is some kind of innate bias towards Muslims. It is, however, a propaganda trick that has worked out very well.”

‘Europe is Hellas, not Persia’

Erdelyi says what the government has managed to do was to start a communication in the media about the migrant person, and what truly mattered was to launch an ongoing debate, whether good or bad, as this benefited the powers-that-be. This way public attention got diverted from other pressing problems such as corruption and other unsavoury state party scandals.

Over the years, Orban successfully deployed the Muslim migrant trope to argue that Islam and its heritage are incongruous with Hungary’s Christian values. He once said that “Europe is Hellas, not Persia. It is Rome, it is Christianity, not a Caliphate.” Orban also conflates Islam with terrorism, as state-funded media zeroes in on some of the extremist attacks across Europe reiterating that migration brings violence, crime and would mean the demise of Hungary, and the decline of the European Union. In 2021 when Bosnia expressed its desire to ascend to the EU, Orban said that it would be a challenge “to integrate a country with two million Muslims,” because of the cultural differences.

In the summer of 2022 Orban also said a very controversial speech in Tusvanyos, Romania at a convention where his sympathisers gathered for an intellectual workshop and festivities celebrating nationalism and patriotism - this is where he said that “Europe was now split in two because of migration,” and those in Western Europe “mixed with other-non European people'' and concluded that “Hungarians don’t want to become mixed-race”, since that would be the end of Hungary as a nation. Orban’s comments caused worldwide uproar, with many critics saying that his words echoed Goebbel’s Nazi playbook. The government's spokesperson Zoltan Kovacs who was live tweeting the event in English deliberately omitted the prime minister’s fascistic thoughts.

Experts say, however, that no migrants want to settle down in Hungary, and only intend to pass through, so the government’s fear-mongering is not warranted.

Justin Spike, who is AP’s Hungary correspondent, has covered the migration beat extensively and says that migrants are bewildered by the government’s portrayal of them.

“Refugees I talked to are afraid to come to Hungary,” Spike says. ”When the prime minister, the state media channels, and state friendly outlets parrot in tandem that migrants are not welcome, as a refugee you certainly don’t feel comfortable here.”

Spike covered the Afghan refugee crisis following America’s withdrawal from the region that once again triggered a new wave of migrants headed for Europe, albeit in much smaller numbers. However the event provided fodder for the authorities. As the 2022 parliamentary election approached, Orban’s campaign among many other elements focused on the trope of the “unruly migrant” and a potential “migrant influx” if the opposition was to be elected.

To back their points, state media pundits reiterated the amount of border entry attempts recorded along the southern border.

Spike, however, conducted an investigation into the government’s claim and used the European Union’s border agency, Frontex’s data, to reveal that the numbers were inflated.

“Many refugees made countless attempts to enter, to no avail,” he says. “The bottom line is, refugees do not want to stay here, because there is hostility toward them and also it is very difficult to obtain papers.”

'Migrants equal terrorism'

To be considered for asylum, petitioners must file a letter of intent at the embassy of a neighbouring non-EU country that is either in Ukraine or Serbia, wait 60 days for the authorities’ response, then if approved, enter Hungary and avail themselves to a border guard or officer to start the official asylum process.

This system has been in effect since the summer of 2020, following the closure of the highly controversial ‘transit zones’ aka the razor wire-lined mobile containers that served from the fall of 2015 as the official areas for asylum procedures until the spring of 2020 when the European Court of Justice deemed them unlawful. The ruling said these zones were effectively prisons, because anyone who entered them became detained, could not leave and had to wait sometimes up to two years without being granted asylum.

“I don’t think that our policies are any different compared to other EU members,” says Horvath, who monitors migration trends and policy for the government. “If you look around, many countries have restricted migration, it’s not only us.”

But experts such as Dr Marta Pardavi, the head of the Helsinki Committee in Hungary, disagrees.

“We are completely going against EU legislation,” Pardavi says. “In fact there is basically hardly any asylum policy in Hungary right now. The country cannot even explain how it grants asylum to those whom it wants to save.”

Pardavi says that the Hungarian government has extensively experimented with suspending EU laws via its ‘migration emergency law’ that has renewed every six month since 2016.

“There is the practice of pushbacks,” says Pardavi. “This clearly goes against EU rules and the Geneva Convention because instead of honouring the refugees' desire for asylum on the spot they are pushed back over the border into Serbia.”

The International Commission of Jurists called the measure an unhinged abuse of emergency powers, since it grants draconian authority to those policing the border. The measure also bypasses the judiciary, the parliament and by proxy defies EU rules. It also allows the government to funnel as much money as it wants for border protection services.

“Meanwhile authorities succeeded in communicating that Islam equals migrants, and migrants equal terrorism,” says Pardavi, whose team has sued Hungary multiple times on behalf of refugees for human rights violations. “Migrant, as a word, had a neutral meaning before, but became sullied over the years.”

Peter Szijjarto, Hungary’s foreign minister, also made a comparison between “migrants” and “refugees” and said that Ukrainian asylum seekers were patient and disciplined, while “illegal” migrants along the southern border were unruly and behaved “aggressively…damaging infrastructure” and “attacked the police”. Szijjarto said that anyone was welcome to come to Hungary from Ukraine, including people from third countries, provided they had their papers in order.

He reiterated Orban’s words that Hungary was not going to relinquish its immigration laws despite the 2021 EU court ruling that struck down the Stop-Soros package of bills. He said that no ‘illegal’ migrants from other countries would be allowed to sneak in with the “flock of refugees” fleeing the war in Ukraine.

“If a person utters so much as ‘asylum’, it means that they need assistance right away,” says Erno Simon, communication director for UNHCR’s Hungary branch (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). His team works closely with Pardavi. He says they are relieved by the EU’s decision on Hungary's asylum laws, even if Hungary has pledged to keep to its immigration policy. Simon says his team remains determined to help refugees regardless of the legal odds.

“Anyone fleeing any war needs immediate shelter and help,” Simon says. “Yet the authorities’ messaging insinuates that there may be some sort of difference between refugees. The fact is, a life is a life, there is no difference.”