As journalists, our fascination with Indigenous communities can blind us to our ethical obligations to respect privacy and dignity of those we document - we must reflect carefully

Just when I thought I couldn't take one more bone-jarring bump along the rough and twisting mountain trails of Chitral on Pakistan's North-West Frontier, the landscape transformed miraculously. I found myself entering a peaceful, forested clearing - the Bumburet Valley, one of the three valleys that make up the Kalash Valleys, near the Afghan border.

As I gazed more closely through the dusty window of our rented jeep, gently massaging my bumped head that had taken a beating during the adventurous ride, I finally caught my first glimpse of the Kalash people - an indigenous community among the world's few surviving tribes.

As a member of the Pakistani diaspora, now based in the UK, I've wanted to meet the people of Kalash and experience their culture since childhood, inspired by countless documentaries on national Pakistani TV channels like PTV (Pakistan Television Corporation).

The Kalash, it is believed, are the descendants of Alexander the Great's warriors, who passed through these lands in 327 BC. Jonny Bealby, author and founder of travel company Wild Frontiers, who lived in the Kalash Valley for three months in 1996, and has since returned many times, has said: "The Kalash are the last of the pagan tribes to inhabit the Hindu Kush. When the British demarked the border with Afghanistan back in 1895, the Kalash found themselves on the British side of the frontier - just - and therefore protected from the Amir’s armies [Amir Yakub Khan]. As such, they have survived from that day to this and are now a protected minority through Pakistan law."

My desire grew even stronger when I witnessed the extensive international media coverage of Prince William and Kate Middleton's visit to this remote Pakistani settlement during their 2019 royal tour, which brought this previously little-known area into the spotlight. Now that I was finally here, my excitement knew no bounds.

Three Kalash women dressed in ankle-length, loose-fitting, black cotton frocks intricately embroidered with vibrant patterns along the neckline, cuffs and hemline, walked gracefully ahead of our jeep. With their backs turned towards me, the majestic Hindu Kush peaks served as a breathtaking backdrop to their journey. Their hair, adorned with the ancestral elegance of brightly-coloured cowrie shell headdresses known as “Shushut”, swayed in the warm, golden sunlight. Each woman's attire was a masterpiece of vibrant hues, creating a living, breathing kaleidoscope. It was like an artist's palette splashed with captivating colours.

I quickly unzipped my bag, fingers trembling with excitement, as I attached the lens to my camera, ready to capture the moment as they strolled by.

It is not enough to parachute in, capture a few striking images, and then depart

"Stop," my inner voice whispered, as if cautioning me not to disrupt this sacred scene. I paused, my finger hovering over the shutter button, feeling the weight of responsibility as a journalist. It is important that I document and share this remarkable human diversity and lesser-known culture with the world. Indigenous stories carry so much educational value, as they have the power to broaden perspectives and foster cross-cultural understanding. However, I was fully aware that it's much more important to seek permission before taking photographs - a journalistic principle that upholds the dignity and privacy of those I was here to observe and portray. This moment of hesitation reminded me of the delicate balance between my duty and my ethical obligation to obtain consent, ensuring that these voices and stories are celebrated with respect and authenticity.

In that moment, I took a deep breath, soaking in the beauty and significance of our first encounter. I watched silently as they walked by, respecting their privacy without intruding as an outsider. However, being a journalist of Pakistani descent, I didn't feel entirely detached. I held a unique position, unlike many Western journalists who drop into remote communities. My Pakistani diaspora background granted me a certain level of familiarity, a shared cultural understanding that made me more than just an observer. Yet, I was still an outsider to their customs, traditions and way of life.

What, then, compelled me to eagerly pick up my camera equipment? Although I would never consider pointing my camera at a random person on the familiar streets of the UK without their consent, there was an intriguing quality about the Kalash community that held my attention. What is it that particularly fascinates journalists and storytellers, and captures the attention of everyone else about Indigenous communities, be it the Kalash, the Mursi tribe in Ethiopia or the Baka people of Cameroon? Is it the undeniable allure of the unknown, the uncharted territories of culture and tradition awaiting discovery?

Maybe it's the striking difference between their lifestyle and our fast-paced, tech-centered world. When we visit Indigenous communities, we feel a bond with nature and a simplicity that connects with our basic instincts. It's an opportunity to get away from the noisy city life and enjoy the peaceful flow of existence.

The Kalash culture is exceptionally rich, with vibrant festivals. Remarkably, they have safeguarded their languages, music, art and rituals even in the face of globalisation. Their polytheistic beliefs and matriarchal social structure challenge conventional norms, setting them apart from mainstream societies. They are a living example of history, guardians of ancient wisdom and traditions, presenting a unique narrative that sparks curiosity and captivates our interest. In exploring such Indigenous communities, we discover a reflection of our shared humanity - a quest to understand, learn and appreciate diverse cultures, embodying the essence of being human.

However, our fascination with these communities often blinds us to the ethical considerations that should guide our actions. Instead of respecting their rights, we sometimes treat these communities as just subjects for our stories. A noteworthy incident from 2020 is documented in Júlio Lubianco's article in the LatAm Journalism Review. It involves the exclusion of the work titled, "Cultures in Conflict", from the finalists in the photojournalism category by the jury responsible for the Vladimir Herzog Award for Journalism and Human Rights. This decision was prompted by a formal complaint from the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY), which complained that the photograph infringed upon the image rights of the Indigenous people featured in it. Indigenous leader Paraná Yanomami conveyed these concerns in a video shared by the Pro-Yanomami Network, stating: "I don't want foreign people to come just to take pictures of my children. People from far away took pictures, and we don't want that... We don't want to be government propaganda."

Similarly, an article published on Forbes in 2022 by Chadd Scott, titled: "Fierce, Not Afraid: Indigenous Photography Takes The Spotlight", highlights that: "Indigenous people have long expressed a legitimate criticism of the camera, a powerful technology with the capacity to discursively impose settler order through its lens." Furthermore, the article emphasises that: "Photography has been used to define, dehumanise, and regulate Indigenous peoples vis-à-vis our contentious relationship with settler culture."

Ethical reporting requires a deep understanding of the cultural context and a dedication to telling their stories accurately and respectfully

It is not enough to parachute in, capture a few striking images, and then depart. True ethical reporting requires a deep understanding of the cultural context, a commitment to building trust with the community, and a dedication to telling their stories accurately and respectfully.

Building a foundation for meaningful storytelling

As our jeep continued its journey, we made the first stop at the Kalasha Dur Museum, which houses a collection related to the culture and history of the Kalash people. Inside the museum, I learned the significance of their clothing items, and understood the intricate structure and design of their traditional homes and temples. For example, the Kalash women wear the Shushut headdresses to set themselves apart from the numerous Islamic ethnic groups in the region, and are a crucial element of a woman's daily attire. This immersive experience provided invaluable insights, ensuring that I approach the Kalash people with a profound appreciation of their heritage. As a journalist, understanding the essence of a place and its people beforehand is an essential foundation for meaningful storytelling.

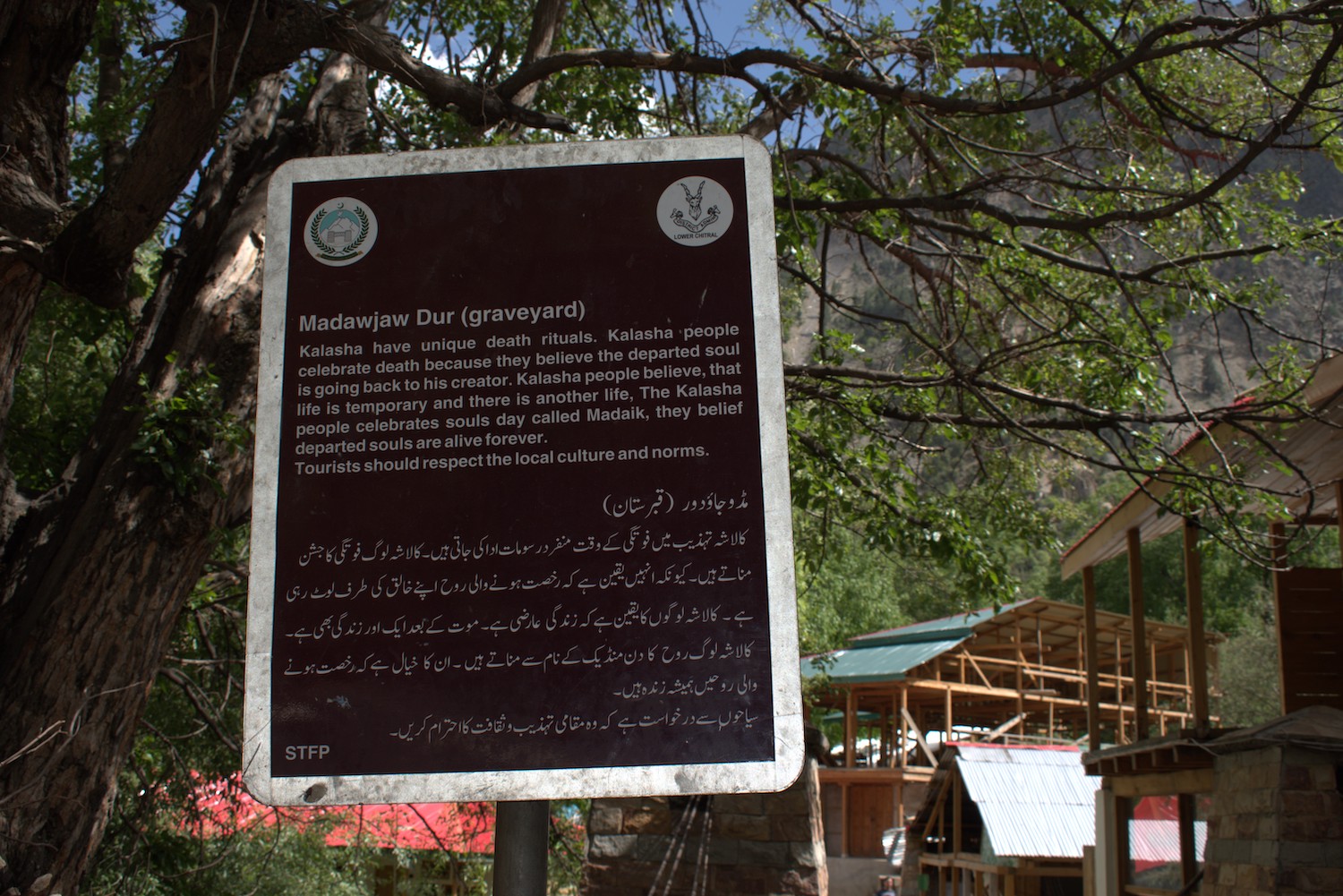

Our next stop was at the centuries-old Madawjaw Dur graveyard, where I discovered the unique customs surrounding the departed. Among the Kalash, death is not mourned but celebrated, and the departed are bid farewell with great respect. This visit deepened my understanding of ancient traditions and cultural sensitivity.

Once we reached our hotel, the Chitral Inn, I sat down with a cup of Chai, surrounded by a backdrop of vibrant flowers and the occasional fluttering butterfly. I started jotting down notes and questions in my notebook, getting ready for my first interactions with this unique community. But, I couldn't help feeling a bit nervous. A language barrier stood between me and the Kalash community. Urdu, my mother tongue and Pakistan's national language, as well as English, were not their means of communication, and I feared unintentionally causing offence.

However, determined to bridge the gap and connect with this unique community, I set out on foot towards a nearby market. Here, I had the privilege of meeting Kalash women who proudly showcased their colourful, handcrafted creations.

Amongst the stalls adorned with vibrant, beaded treasures, a young Kalash woman named Amrina stood out, her eyes alive with warmth and curiosity. Climbing a narrow, winding staircase, I stepped into her dusty wooden boutique, complete with a balcony seating area. I couldn't help but touch the intricate embroidery on the beautiful dresses and headpieces on display. Amrina noticed my fondness for these items right away.

As a journalist, understanding the essence of a place and its people beforehand is an essential foundation for meaningful storytelling

"Would you like me to assist you in trying on one of our dresses?" she gently asked in flawless Urdu. I was pleasantly surprised by her fluency and the discovery of a common language between us. Her offer was unexpected, yet it resonated with the hospitality often associated with the Kalash people. I accepted her offer, eager to embrace this unique opportunity to be a part of the Kalash culture, even if only for a brief moment.

She draped me in one of their rich black dresses, cinched the pat'i - a sturdy woven belt - around my waist, with a firmness that mirrored their unwavering heritage, and crowned my head with a brightly-coloured cowrie shell cap. As she expertly braided my hair like hers, I gazed at my reflection through the selfie camera and felt that I wasn't just a journalist, I had become a part of this Indigenous world.

'Not many people ask for permission'

Amrina allowed me to wear the attire throughout the day and kindly offered to give me a tour, with no expectation or pressure to make a purchase. This gesture spoke volumes about her openness and generosity. Together, we walked through their village, exchanging nods of respect with each family we passed, until she led me to her home. Walking around in the Kalash attire, I felt a mixture of privilege and the weight of responsibility. I wasn't just an observer anymore, I was a participant, and it's an experience that fills your heart with a profound sense of connection and understanding. It wasn't just a costume that I was wearing, it was a bridge that allowed me to see the place through their eyes.

She welcomed me into her traditional wooden-structured home, and over walnuts, we shared stories of music. Her eyes sparkled with passion as she told me she had the privilege of participating in a song recording for Pakistan's renowned music platform, Coke Studio - a highly acclaimed music series in Pakistan that features live studio recordings of diverse musical genres. In her sweet voice, Amrina sang her Coke Studio debut song "Pareek" to me, showcasing the beauty of her native Kalasha language. When I requested permission to record and capture photographs of her, she was pleasantly surprised and appreciative.

The stories we tell are not just opportunities to document but chances to connect, bridge divides and foster understanding between diverse cultures

"Not many people ask for permission," she remarks. "We appreciate when tourists and explorers come to visit us. In fact, we enjoy interacting with people from all walks of life." Her gratitude was evident, but she also expressed a strong concern, saying: "However, I really don't like it when people take photographs of us or enter our homes without seeking permission. I know we may look different to others, but it's not nice to enter someone's village and take photographs without asking."

As I recorded her singing, her melodious tunes resonated not only with the Kalash community but also touched the depths of my own Pakistani heart. In that moment, a special connection emerged that transcended language and distance. Encouraged by our mutual admiration for beloved national singers like Atif Aslam, I couldn't help but request more songs from Amrina. The fact that she could speak my mother tongue added an extra layer of comfort and joy to our interactions. Through the medium of music, we effortlessly bridged the gap between insider and outsider, discovering common ground in the universal language of melody and emotion. This helped me establish a bond of trust and respect that might have been harder for an outsider or a Western journalist to achieve.

Amrina went on to share more about their unique festival, “Chilam Joshi”, which was set to begin in a few days. They were currently busy weaving new dresses for the occasion. The Chilam Joshi celebrations take place in May, serving as a tribute to the arrival of spring. The festival is marked by vibrant clothing, traditional music and dance performances.

Amrina had a mobile phone and was well familiar with the world of TikTok, revealing that Indigenous communities aren't as disconnected from modernity as one might assume. After capturing some selfies and exchanging heartfelt goodbyes, I returned the precious outfit of the day with a warm smile.

Before departing, we exchanged contact numbers. It's essential to extend our efforts beyond one-time reporting and instead focus on cultivating long-term relationships - a commitment to fostering enduring connections with indigenous communities. This commitment involves revisiting these communities to follow up on stories, provide feedback and support initiatives aimed at cultural preservation and empowerment.

My journey among the Kalash, coupled with my diaspora background, has enriched my approach to reporting on Indigenous communities. This experience has provided me with a framework, guidance, and a unique perspective for engaging with indigenous people worldwide. I have learned that the key to responsible journalism in Indigenous communities lies in building relationships founded on trust, reciprocity and a genuine desire to understand the nuanced realities these communities face. It has taught me that the stories we tell are not just opportunities to document but chances to connect, bridge divides and foster understanding between diverse cultures.