THE LONG READ: Afghanistan ranks as one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists. Yet despite targeted killings and an uncertain future, many Afghan reporters are determined to stay and bear witness.

Kabul, Afghanistan – It was about 8am on a Monday morning in April 2018 when Bushra Seddique felt the multi-storey apartment building she was living in with her family in Kabul’s Shash Darak district shake. Smoke billowed from the street below.

She barely had time to process what was happening as her father rushed the family out of the house, past the injured and the dead. But she does remember seeing journalists running, cameras in hand, towards the scene of the explosion.

Half an hour later, a second explosion went off; nine reporters who had arrived at the initial blast site were killed.

It was the first time Seddique, now 21, had witnessed the dangers that Afghan journalists face. “It was traumatic, but inspiring to see their bravery and commitment,” she says.

At the time, Seddique was in the second year of her journalism programme at Kabul University. She has since graduated and has begun to embark on her career with a mixture of determination and trepidation.

But, on August 15, the Taliban swept to power, leaving journalists and independent media to face an unknown future - one where it is no longer easy to run to the front line. During the previous Taliban rule, more than 20 years ago, independent journalism was nearly impossible.

And so, hundreds of journalists, as part of an exodus of more than thousands of the country’s best and brightest, have left the country for fear of their security.

Over the last few years, we have lost many journalists to bombings and targeted killings, and this is tragic and scary - Bushra Seddique, Afghan journalist

The Taliban leadership has not clearly communicated how the media will be governed. It has merely stated that the media can operate so long as it does not “contradict Islamic laws or harm the national interest”.

In recent days however, journalists have been attacked and their family members hunted - putting the Taliban’s promises of a “free media” to the test.

Afghan reporters are no strangers to what this could mean.

“Over the last few years, we have lost many journalists to bombings and targeted killings, and this is tragic and scary,” Seddique explains. “It’s disappointing for me and anyone trying to grow their experience as a reporter.

“But I still want to continue. By choosing to pursue journalism, I have already accepted the barriers and difficulties of working in this field in this country.”

Seddique says she fully understands why, despite the inherent dangers, Afghan journalists continue to pursue this career. Prior to the takeover by the Taliban, she wanted the world to see Afghanistan as more than just a conflict zone and hoped, through her journalism, to offer an alternative to the typical portrayals of her country in Western media.

“Afghanistan has so much ancient history and a vast wealth of culture. I want to tell untold stories of ordinary people,” she says.

“I believe that journalism is not just a job or subject,” she adds, emphatically. “Pursuing journalism is a desire for change and to help.”

A risky profession

Journalism is one of the most dangerous professions in the country. According to Reporters Without Borders, at least 85 local Afghan journalists have been killed in connection with their work in the past 20 years. After the Taliban seized control of the country in 1996, journalism went from being severely restricted (as it was during Soviet rule) to almost non-existent. Television sets were destroyed and all TV news channels disappeared overnight. Photos, commentary and newspaper editorials were banned, and most print and media publications were shut down. Only strict religious radio programming and propaganda news articles for one newspaper – The Islamic Emirate – run by the Taliban, were permitted.

After the US and NATO invasion of Afghanistan and the toppling of the Taliban, the country experienced rapid growth of the media sector. Numerous television news stations, radio programmes and more than 1,000 print media sources existed in the country prior to August 15. Two of Afghanistan’s largest independent newspapers - Etilaatroz and Hasht e Subh are still publishing news daily.

As a career path, journalism is not something many Afghan families are eager to encourage due to its perceived danger and employment uncertainty. Reporters will often sign employment contracts with domestic media outlets without safety clauses or insurance benefits because of the high unemployment rate.

There are also limited positions with good salaries. In Afghanistan, there is no minimum wage, and each media organisation pays its staff according to its own pay scale. The average income for an Afghan journalist depends on experience and whether they are working for a domestic or international outlet. Local outlets pay a wage typically ranging from $200 to $1,000 per month, while international outlets can pay between $600 and $3,000 per month. Entry-level graduates are paid at the lowest end of the spectrum.

Still, there are 12 state-run universities offering journalism programmes across the country whose continued operation depends on how education is set up going forward. The Taliban-run Ministry of Education has approved a proposal put forward by Afghanistan’s union of universities that outlines the separation of females and males.

Images have circulated recently showing female and male students resuming classes in Avicenna University in Kabul, but divided by a curtain. It is not clear whether this is by a Taliban directive or just a protective measure.

At Kabul University, where Seddique studied, 1,152 students were enrolled in undergraduate journalism and communications programmes in the last year, with an almost 50-50 split between men and women.

“They pursued their undergraduate degree with a passion for contributing for the good of this country,” says Abdul Qahar Jawad, an associate professor of Journalism at Kabul University and Seddique’s former tutor. However, he admits that journalism is not usually a student’s first choice; it is a career they learn to appreciate with experience and practice.

Seddique understands this because journalism was not her first choice either. She grew up wanting to become a doctor or a lawyer but, in secondary school, her score in the country’s national Kankor university entrance exam process placed her in journalism, her third choice.

All Afghan secondary school students looking for a place at one of the country’s universities must take the Kankor exam. Students compete for spots alongside other candidates from their home province, and their score is the sole determining factor for admission to a university department.

Students may choose five fields in order of preference when they take the national exam but, beyond that, the choice of where they are offered a place is out of their hands. Seddique was not disappointed with her outcome. After all, she had earned a spot at Afghanistan’s top university against a highly competitive pool of applicants.

As an undergraduate, one of the first stories she worked on was about people living in poverty on Sar-e Yakhdan, a remote rocky hill to the west of Kabul. It took a day to travel to and from the mountain.

“I was a student and travelling by myself as a young girl to report a story. In Afghanistan, this is not common behaviour for young women,” she explains. “I remember men staring at me with disgust and asking me why I was on the street by myself, some very harshly. I felt insecure and scared.”

Another time, while interning for a national newspaper during her second year at university and working on a story about some of the most crowded marketplaces in the city, shopkeepers shouted insults at her. One of them called the police, who questioned her on the street and subsequently told her to leave the area.

Saleha Soadat, an experienced Kabul-based reporter, puts such incidents into perspective. “Women don’t have security. During the Taliban era, women were hidden under burqas. After their departure, we re-entered society but were still relatively unseen and persecuted, even sexually harassed,” she says. “The media space is male-dominant with a negative view towards women. Some men still think that women working in a media outlet are immoral.”

Besides harassment, targeted shootings outside workplaces and homes have been a risk, as well as secondary bombs set to detonate after initial attacks with the aim of targeting journalists and rescue crews arriving at the scene of the first bomb - like the 2018 attack Seddique witnessed from her apartment window that killed nine journalists.

‘Prejudice, inequality and terrifying violence’

Journalists covering conflict must walk a dangerously thin line, balancing threats to their lives from armed groups on the one hand and threats to how they carry out their profession from the government’s security forces on the other. The lines between enabling propaganda, intelligence gathering and journalism sometimes blur as they relate to reporting and source protection in Afghanistan. Given these types of challenges, many Afghan journalists have become accustomed to a degree of self-censorship as a form of self-preservation.

While international forces were present in Afghanistan, some journalists covering Taliban activities - particularly those with direct access to members of the group - found themselves being arrested on charges of “collaborating” with the Taliban and “spreading propaganda”. In some cases, journalists say they have been forced to work for the intelligence services or face arrest. Then there are those who have been kidnapped or assassinated by the Taliban for supposedly working with the intelligence services.

If the international community is quiet about this violence, and journalists continue to be targeted, then no one will want to work in this field - Bushra Seddique, Afghan journalist

Targeted killings of journalists by armed groups increased significantly amid the final US and NATO troop withdrawal. Even before the mass exodus following the Taliban takeover, many Afghan journalists fled the country in fear over their security.

Female journalists, in particular, have been targeted in record numbers.

According to Soadat, there have only ever been a handful of female journalists in Afghanistan compared to males. “The split between male and female journalists is roughly 80 to 20. Afghanistan is patriarchal, and journalism is still considered shameful work for women today,” she explains.

There are also not enough journalism roles. In 2020, the unemployment rate in Afghanistan was more than 11 percent. Women, whatever their education or experience, are often overlooked for competitive positions across all industries.

Since the Taliban seized power in August, Reporters Without Borders and the Centre for Protection of Afghan Women Journalists have reported that only 39 female journalists are still working for private media in Kabul.

Even before the takeover, the ongoing targeted killings have left citizens feeling uncertain about the future of the country. According to Afghan journalist Zakarya Hassani, who was based in Kabul until he left the country, there has been a reduction in “freedom of speech, and more fear about what is going on in a critical, historic juncture of Afghanistan”.

There are consequences for this, he says, in the form of a “brain drain and loss of hope”, as journalists and others like him leave the country. Right now, Afghanistan is experiencing a great loss as streams of professionals flock to leave the country.

As someone just entering the industry, Seddique reflects upon the consequences of targeted killings. “If the international community is quiet about this violence, and journalists continue to be targeted, then no one will want to work in this field,” she says. Right now, for many Afghan journalists, Taliban governance signals the end of press freedom and independent journalism.

Fuelled by desperation

Seddique’s mentor and former university professor, Jawad - himself a student-turned-educator of journalism - has been helping to foster the mindset of journalism students for years.

He attended Kabul University from 2001 to 2004 and became a professor at the institution afterwards. When he was first a student at the university, his department head was a Taliban official. Though they were under strict Taliban rule, “he treated us like humans”, Jawad says as he reflects on the country’s previous period of Taliban rule.

Jawad says, then, students spent 60 percent of their time studying Islamic law and 40 percent on their other subjects. They had no access to computers and had to transcribe lectures by hand. Women were not allowed to study or work, only re-entering classes during his second semester in 2002 after the Taliban had been toppled.

During his tenure as a professor, Jawad has been awarded the prestigious Fulbright scholarship, which took him to the University of Arkansas in the US to complete a Masters in Journalism. After he graduated, he decided to return to Afghanistan because he wanted to continue working for Kabul University.

“To be a lecturer at the journalism school guaranteed me an employment opportunity in 2005 after my undergraduate studies. I didn’t see beyond that economic opportunity at the time. But gradually, while teaching, I started appreciating the significance of journalism for my personal career and its social and professional impact. I was empowering younger generations to flourish and to be the eyes and ears of their communities. So I wanted to continue teaching and to become part of a fabric that would drive change in my country through journalism,” he says.

Jawad recalls being scolded by relatives for giving up the possibility of potentially staying in the US, but is adamant he made the right decision. His eyebrows furrowed, he explains: “I came back because I saw an opportunity to be an influencer, to educate a generation that could change the situation that generations, including myself, have grown up in.

“These are young generations that are eager to learn and bring change for Afghanistan and, perhaps, the world. I can’t fix all the problems in Afghanistan, but my country needs people who were brought up here to contribute to helping the country.”

He believes in students like Seddique and understands the motivations of those who grew up in conflict.

As well as the previous Taliban control, Jawad also lived through the Soviet era. He recalls walking 16km (10 miles) a day as a child to sell vegetables out of a cart as rockets fell around him. The increasingly violent conflict between Mujahideen groups following the Soviet withdrawal forced him to stop going to school for nine years, and he had to rely on private schooling later in life to catch up on his studies.

“As I was working, I desperately observed other children my age attending schools with notebooks in their hands, as people then could rarely afford to buy school bags,” he recalls. “Sometimes, in these instances, I stopped to think whether my destiny could be different in adulthood if I could continue going back to school.

“This feeling of desperation fuelled me to find partial schooling that would align with my responsibilities to my family. So I attended some small-sized education centres to catch up on my studies in a few subjects like English, mathematics and calligraphy.

“These were baby steps, but they helped a lot when I was able to resume schooling officially. My experiences taught me commitment and resilience. Millions of youth across Afghanistan have faced and still face similar situations. Still, I hope as an educator I can inspire others who are struggling never to give up.”

Prior to the Taliban takeover, Jawad oversaw a competitive journalism programme (the fifth-largest programme at the state-run university). It accepted only 300 candidates out of the 2,000 who applied each year through the national examination process.

He knows the programme still needs advancements, but he sees hope in what it stands for – in the way it has prepared the next generation of Afghan journalists, those who are looking to reframe Afghanistan’s narrative as it enters an uncertain future.

Seddique is part of that generation. She admits that it is sometimes scary for someone who is just starting out in the industry. But she is determined and persistent. She knocks on doors until she gets interviews and works extra hard to research and fact-check because sources often provide her with false information. “If people ignore me, I return every day until someone speaks to me,” she says.

Seddique, who is ethnic Tajik, credits this mindset to her open-minded family, especially her supportive father, who she says “always believed that a key driver to change in this country is education”. And she and graduates like her draw inspiration from female journalists who have paved the way for them - journalists like Soadat.

‘How can I remain silent?’

Now 34, Soadat remembers only violence from her childhood. She grew up in west Kabul during the civil war and was forced to flee her home when it was attacked by an armed group.

In a society that does not even spare children, how can I remain silent and not fulfil my mission as a journalist? - Saleha Soadat, Afghan journalist

While fleeing, she and her sister were injured in a rocket attack. In a panic, her mother covered their wounds with her clothes, and they escaped with other relatives underground. Those memories and the thought of her mother desperately trying to protect them haunt her to this day. And now, she has had to flee again. She left Afghanistan on a military plane for the US on August 20. She’s trying to continue reporting and sharing news via Twitter.

“In a society that does not even spare children, how can I remain silent and not fulfil my mission as a journalist?” she asks, sitting tall with her hands crossed in her lap.

“I started my career with radio so that only my voice could be heard,” she says, explaining that her family were concerned about her safety. She previously worked for TOLO News as a senior political reporter, and now works as a freelance journalist.

Soadat is no stranger to discrimination and targeted violence. She is Hazara, one of Afghanistan’s largest ethnic groups, comprising roughly 20 percent of the 38 million people who live in the country. Hazaras have been historically and systemically persecuted and discriminated against due to their Shia faith as well as by Afghanistan’s Pashtun-and-Tajik-dominated government, despite being granted equal rights in the 2004 Afghanistan Constitution.

Since 2018, there have been more than 50 Taliban and ISIL (ISIS) attacks targeting Hazara civilians everywhere from mosques to hospitals. In May, there was a massacre at a girl’s school in a primarily Hazara community.

Soadat believes that if local journalists, who are closest to the challenges the country faces, do not report on such matters, there will never be progress.

She credits her commitment to journalism to her mother. “As a child, my mother always told me to strive for myself, my family and community. My mother inspired me to be a good human being first, and I think I chose to pursue journalism because of what she taught me.”

She worries about her future and the future of journalism now after the Taliban takeover.

“Journalists are at the forefront of the country’s struggle because they voice facts. These voices may be to the detriment of the Taliban,” she explains. “The withdrawal of foreign troops will undoubtedly affect the deteriorating security situation.”

But she is not ready to give up and believes the next generation of journalists - those like Seddique - must believe firmly in what they are doing. They have to keep running to the front line, she says, because “journalism is a window to change.

“In Afghanistan, it’s dangerous, but journalism is sacred work.”

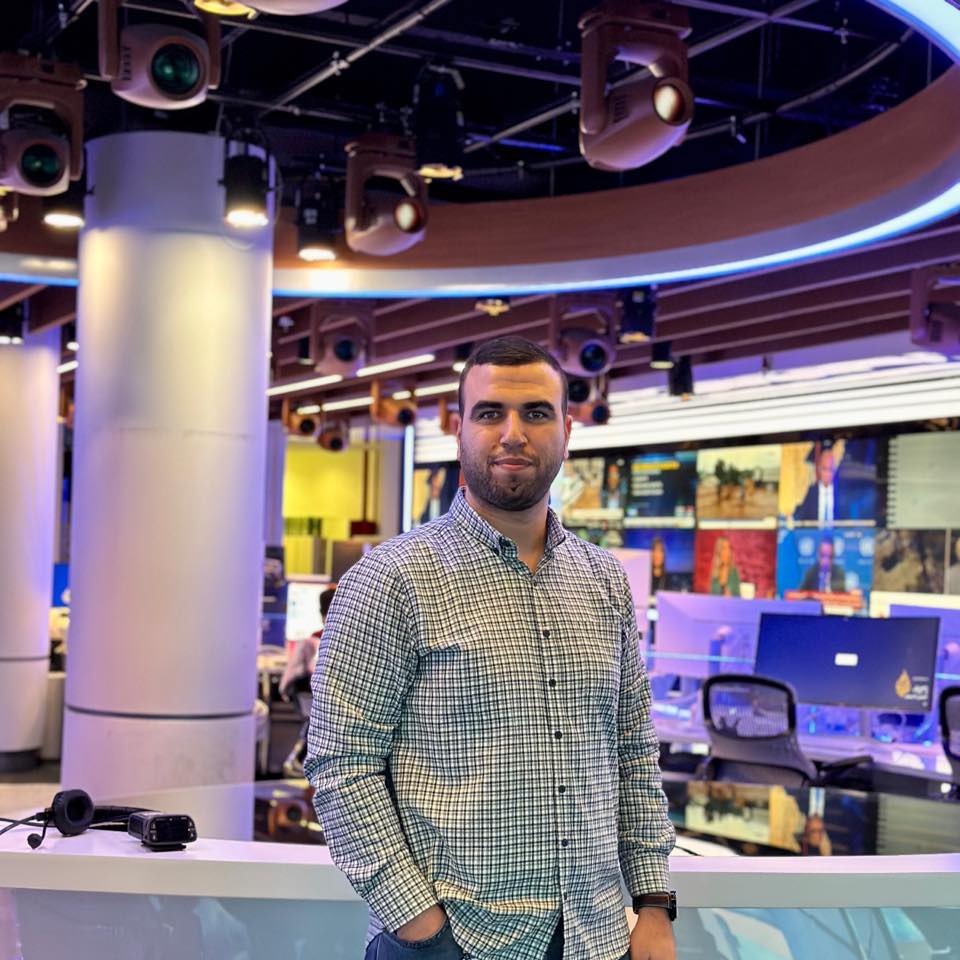

Main image: Bushra Seddique at her office in Kabul before the Taliban takeover in August [Photo by Barialai Khoshhal]

An earlier version of this article first appeared on Al Jazeera