On Thursday, August 26 – less than two weeks after the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan – explosions rang out near the airport, where thousands had been crowding, attempting to flee the country in fear of a return to the group’s brutal rule of the 1990s. More than 170 people were killed and at least 200 wounded. Journalist Alireza Ahmadi, 35, was among them. This is his story.

The last time I spoke with Alireza was the night of August 25 – the night before the deadly explosions in front of Abbey Gate of Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport, where my best friend would experience his last moments in this world.

I sat in my hotel room in Paris – where I have been since fleeing Afghanistan in the wake of the Taliban takeover – while Alireza was in a small, rented room at a private male dormitory in West Kabul.

Most of his family was in Herat, so he lived on his own. He had just gotten engaged to his fiancée three months ago and was ready to start a new chapter of his life.

Although we were worlds away, it still felt like we were together, talking in person.

Our conversations had never been light or easy, even when I was in Kabul. Being an Afghan journalist has its challenges but we had the added struggle of being from the persecuted Hazara community. Our lives as outspoken individuals were constantly under threat, but our friendship and mutual support helped us through some difficult times.

We tried our best to keep each other upbeat amid terror threats, the daily risks we faced doing our jobs as we covered bomb blasts and exposed corrupt officials. We shared our concerns over what the future may hold for us. It always felt like we were living from one day to the next, running against time, without any certainty about what would happen next.

Alireza was a dedicated Afghan journalist – selfless, hardworking, talented, driven, and motivated to amplify the Afghans voices, especially those of his Hazara community.

Growing up as a refugee in Iran, he suffered hardships and faced a life of constant discrimination as a minority. He spent most of his childhood in Tehran where he finished school.

After the Taliban regime collapsed in the months after the US invasion in 2001, Alireza and his family relocated to Afghanistan to start a new life. They settled in Herat city.

Alireza moved to the capital some years later to study journalism at Kabul University and got his Bachelor’s degree in 2010.

He spent the last 10 years covering news across Afghanistan for many local outlets, including Rahapress, Sadaye Afghan News Agency, and the daily Rahe Madanyat newspaper. He was most recently an investigative reporter for government-supported newspaper AfghanistanMa. He covered breaking news stories and did in-depth reporting through his features and investigative reports on topics that ranged from policy to economics.

‘He wanted to be seen and not silenced’

Alireza was a brilliant reporter, writer and photographer. But, like many Afghan journalists, he faced danger due to his reporting, for referring to the Taliban as “terrorists” in his reports. We’d often share stories about the threats we received and would advise each other on how to stay safe.

Alireza always inspired me with his ideas and how he expressed his views. He was a person who constantly strived for liberty, democracy and equality. He wanted to be seen and not silenced. He was one of the most fearless individuals I have ever known.

Our last conversation was nothing out of the ordinary. He expressed concern about his high levels of stress and feelings of depression; he told me he could not sleep, all of which I could very well relate to.

For months and years leading up to the Taliban takeover, and my final escape from Afghanistan, I too experienced stress, debilitating sadness, and insomnia.

During our phone conversations, we tried hard to figure out how to get him out of Afghanistan as soon as possible.

Alireza had not worked for any foreign news outlets, hence he could not get any support to get a visa nor was he included in any evacuation list.

He knew he was on his own.

So, he decided to go to the airport to try his luck. He and his younger brother Mojtaba had heard that people without papers had made it through. Mojtaba, 30, had already tried once before, unsuccessfully.

On August 25, we talked until the early hours of the morning, thinking we would continue our discussion the next day.

It was to be our last conversation. I wish I could turn back the clock and hear his voice one more time.

As the phone call ended, I wished I was still with him.

But ever since the Taliban started gaining military advances four months ago, I knew that I had to leave Afghanistan. As a new father to a one-year-old baby, I had no choice but to find a way to get my family to safety.

When the US and its allies started to leave, everyone was a bit surprised at how quickly the Taliban started to make gains. And when Ashraf Ghani fled Kabul and handed power to the Taliban, I was floored.

I had always known there would be an imminent threat to my life if the Taliban took over.

In 2015, I was part of a 1TV team that exclusively covered the battle of Kunduz city in the north. The Taliban officially released a statement declaring our reporting team a military target. But I never stopped reporting on their atrocities. As journalists, it is ingrained in us to continue reporting the truth despite the risk.

Fortunately for me, I have been a Persian correspondent for the French media organisation Radio France Internationale for the past three years. The day the Taliban took over Kabul, they secured our visas to France. I left Kabul with my wife and daughter on a French military plane to Paris, arriving on August 19.

I started receiving messages from fellow journalists seeking help to escape. As some of us started to leave, many others began to pack a few belongings, desperate to figure a way out, not knowing what their next move should be.

It felt like a chain reaction.

One thing we all knew was that Afghanistan would not be the same under this new government.

‘I couldn’t breathe’

When I first heard the news of the explosions, my mind went blank and I completely panicked.

Before the attack, I had heard there had been a lot of chaos with thousands of people – with and without documents – queueing along the perimeter of the airport in a desperate attempt to escape.

I feel distraught thinking how everything collapsed in a matter of seconds.

I have a lot of family members and friends who are still in Kabul, it was challenging to find out where everyone was and that they were all safe.

At around noon on August 27, I received the call I wish I never had.

One of our mutual friends called to say that Alireza and Mojtaba had both left for the airport the day before, and nobody had heard from them since the explosions.

I feared that no news may not be good news.

I felt numb with shock. I couldn’t breathe, like my whole being was completely engulfed in this darkness that suffocated me.

Immediately after the call, I asked some of our mutual journalist friends in a Facebook group to search for Alireza in nearby hospitals where the wounded had been taken.

And I started to pray, out of desperation. I prayed fiercely that somehow someone would call and say that he was never there and that he was safe and alive.

I had to distract myself, so I spent a while poring over our last conversation threads and his last social media posts.

A day before he passed (August 25, 5:48 am), he wrote that he had sold 60 of his books for 50 Afghanis (less than $1). When a friend asked him why he did that, he responded, “because I have to emigrate”. He knew he wanted to leave.

After four hours of intensive search with his cousin, our friends found his body at Jamhuriat hospital. He was barely recognisable, but his cousin identified his face.

They also found his tazkira (Afghan ID card) in his pocket.

Mojtaba is still missing.

When I heard the news of Alireza’s death, I was shattered and couldn’t stop myself from sobbing uncontrollably.

A million thoughts raced through my head, wondering what his last moments must have been like, how much pain he had had to endure.

Several moments from our seven years of deep and sincere friendship flashed before my eyes.

Alireza often worried about terrorist attacks, and of becoming a victim of one. He had bluntly said in the past that he would rather die quickly in an explosion than be tortured, but I had hoped that he wouldn’t be killed at all.

He was one of the more than 170 people killed. Many more were injured, and several are still missing since the deadly attack that ISKP has claimed responsibility for.

It is a tragedy adding to the turmoil the country is already in.

His tragic and untimely death has been particularly heart-wrenching for the Afghan journalist community.

As journalists, it is our duty to reveal the truth – and as Afghan journalists, we have been exposing corruption, terrorism, and all the wrongs that have contributed to the state that the country is in today. And for that, we have had to pay, sometimes with our own blood.

Several of our fellow journalists had already been killed in the years before. In the last five years, 27 local Afghan journalists have been killed in Afghanistan, in targeted killings or crossfire.

Journalists across the country are being targeted, beaten up, killed, and their family members hunted down. Those who remain in the country risk a dark future. There will be no more free speech for Afghan journalists.

But our people support the work we do.

There have been countless posts on Twitter and Facebook in the past few days, acknowledging Alireza’s contribution to journalism in Afghanistan.

He was known for his humility, honesty, and dedication. He was loved dearly by his family, friends and colleagues.

And so, while I feel immense pain for the loss of our friendship, I know there are gaping holes in many lives right now as we all grapple with the loss of our dear Alireza.

He was and always will be one of my best friends, and more than that, my brother. I will hold his memory in my heart, forever.

As I write this, I cannot stop tears running down my face. Each and every inch of my body feels the pain of his loss, but I will try to find comfort in knowing that I got to develop a special friendship with a special individual.

I will remember our interactions, our memories. And most of all, I will remember his cheery face and his bright smile. Despite his suffering, he always remained positive. His death is a loss not just for those who knew him, but also for those who will only come to know of him now that he is no more.

As told to Robyn Huang

This piece was first published on Al Jazeera

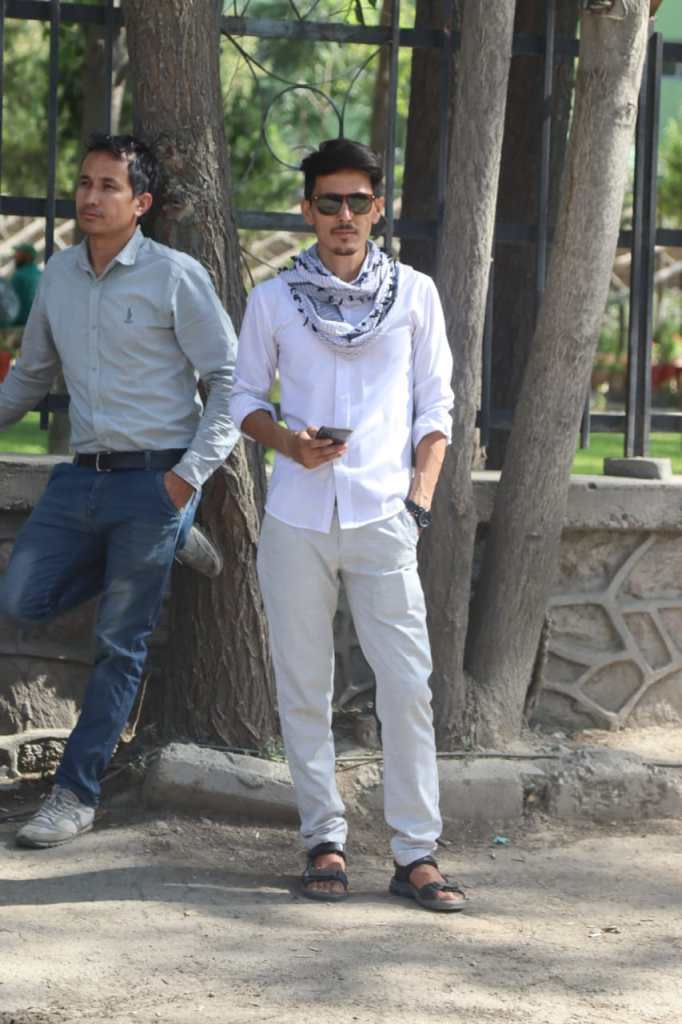

![Alireza, left, and Zakarya met on a reporting assignment in Kabul in 2014 [Photo courtesy of Zakarya Hassani]](/sites/default/files/ajr/2021/Alireza3.jpeg)