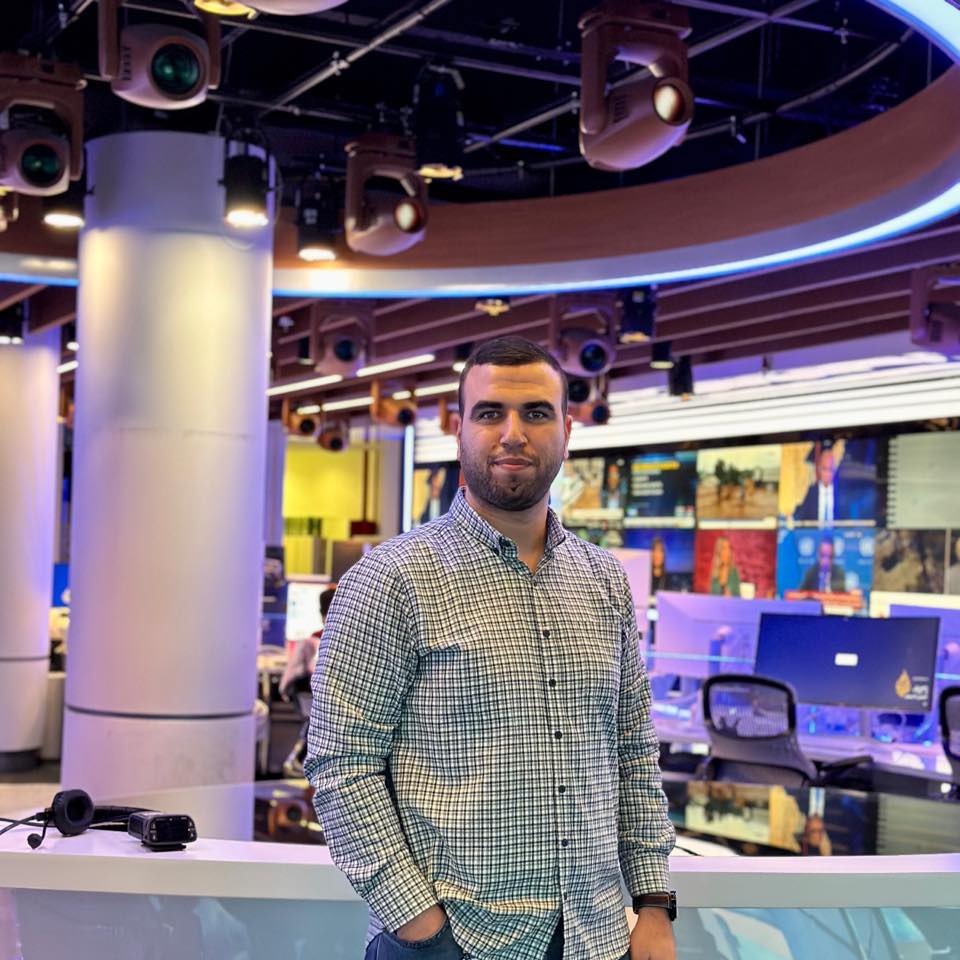

Omar Al Hajj, a Syrian journalist working for Al Jazeera, explains what it’s like to go from covering war in his own country to bearing witness to another on a different continent

The war in Ukraine was front-page news all over the world before the first bullet was even shot. No war in the modern age has had quite the media response as the one going on in Ukraine. But it is far from the only war which is causing mass human suffering and displacement, and certainly not the only one journalists have been covering for the past decade.

In Syria, where war has been raging for 11 years, millions have been displaced while the regime - backed by Russia - has deployed chemical weapons considered illegal in modern warfare against rebels as well as civilians. Only a handful of journalists from Western media outlets have remained, leaving it to Syrian journalists themselves to tell the world what is happening to their own country.

Omar Al Hajj, now reporting for Al Jazeera from Kyiv, was one of those journalists.

There are parallels between the two wars - for one, Russia is a main aggressor in both. “But in Syria it was impossible to act freely as a journalist in the field,” says Al Hajj. “The chances of getting killed by an airstrike were very high, and I felt compelled to take many more risks than I’m taking today in Ukraine, because, simply, it was my homeland.”

A ‘legitimate’ target

Then, for Al Hajj, there is the matter of remaining neutral as a reporter. Can a Syrian journalist who is witnessing, on a daily basis, the killings of the hundreds and displacement of hundreds more truly separate himself from his feelings?

As for many journalists covering war within their own countries, the work is deeply personal to Al Hajj. “The suffering of the victims is at the centre of my interest, not just getting the news.

“I did not see my father for more than eight years - my brother for more than nine. So, suffering is always present in my stories. That is the essence of journalism that I believe in.”

So far, the experience of being a journalist in Ukraine has been markedly different from Syria, says Al Hajj. “In Syria, journalists are viewed as legitimate military targets by the Russians, and wearing that 'press' vest just makes you an obvious target - without hesitation."

In Ukraine, journalists - so far - have received different treatment. “I’m talking to you now from a hotel where dozens of journalists from different media outlets are staying,” Al Hajj explains. “The Russian army is doing its best to avoid targeting journalists.”

Furthermore, in Ukraine, he is working with a full television crew, whereas in Syria he was often the cameraman, the reporter and the producer, all rolled into one. “I was doing everything on my own.”

Musings on covering war

While Al Hajj grew up in Syria and is therefore highly knowledgeable about the context, history and reality of the war there, he found himself in the new position of having to learn about the history of Ukraine and Russia, like any other foreign journalist must do about Syria before coming to his own country.

“Before my arrival in Kyiv, I read about the history of the country and that of the Soviet Union. I studied the background and history of the two sides and read about linguistic and cultural variations within the country, economic aspects and military abilities. This is vital information that any journalist who is eager to cover a war in a balanced and professional way should know.”

There is always a balance to be struck between covering events on the ground and ensuring the safety of your crew. “The safety of the crew comes first always,” says Al Hajj. “The scoop is never important enough to risk your life for it. That’s why we always try to read the armies’ regulations about safe paths in war zones, before we go out to coverage, or at least follow the press releases of the armies’ spokespersons. That doesn’t mean that we will blindly follow their narrative, but we will try to maintain our safety as much as possible.

“We need to be aware that we are covering a war, nothing less.”

The official narrative is important, but..

There is also the issue of evaluating the narratives coming from either side during a war. “In covering the Russian war on Ukraine, we basically rely on the statements of the two fighting states, but that doesn’t mean that we accept them unquestioningly.”

In the case of Ukraine, the official narratives from both sides are wildly different, with Russian claims of “liberating” Ukrainians from a “fascist” government - a notion which is provably false.

So how does he make judgement calls? Al Hajj says he believes what he sees with his own eyes. During field coverage, interviewing eyewitnesses and observing the military progress on the field, are the main ways to form a perspective away from the official narratives.

He does not repeat statistics and data by rote. “I do report the numbers that the Ukrainian defence ministry declares about the Russian casualties, but I always state the source,” he says. He also maintains a healthy scepticism, no matter where the information is coming from.

For example, Ukrainian official statements denied that the Russian army had entered Bohodukhiv City in the Kharkiv province of eastern Ukraine. So Al Hajj went there and saw for himself that this was not true. “I didn’t state that those reports were wrong clearly on the live coverage, I just stated what I could see for myself: ‘We are on the city borders and there are Russian tanks.’.”

Finding sources who will contradict any official narrative can be very hard, however. “We have to remember we are in the middle of war, and the authorities’ mood is aggressive, so everything anyone says is being monitored.”

The importance of language

Al Hajj also says that journalists covering war must be very careful about the terminology they use to describe events on the ground. Around the world, the war in Ukraine has been variously described by media outlets as “the Russian invasion”, “the Ukrainian crisis” or “Russian aggression”.

“From the outset, Al Jazeera was very clear in its terminology, and you can see that clearly when correspondents use the phrase ‘the Russian war on Ukraine’.” says Al Hajj. “We must provide balanced and unbiased coverage of both sides, without any emotional or editorial bias. What we care the most about, is reporting the absolute truth away from the political conflicts between the ‘east’ and the ‘west’.”

He adds: “If we are covering a massacre, its aftermath and its effects on people, it should be described as it is seen by the journalists covering it.”

Translated from the original article by Muhammad Khamaiseh