How political cartoons have evolved in recent decades in southern Africa and are now shaping public discourse in Zimbabwe

Political cartoons may appear to be simple, innocent commentary sketches, but in a polarised country like South Africa or Zimbabwe, where political sentiments are constantly scrutinised, they help to initiate robust debates.

Defined by Britannica as “an artistic vehicle characterised by both metaphorical and satirical language, that may point out the contexts, problems and discrepancies of a political situation”, a political cartoon is typically designed to speak truth to power, but can attract trouble, especially from political figures who may feel demeaned or aggrieved.

From past records, political cartoonists have attracted fame, hate or even been killed. In 2008, former South African president Jacob Zuma filed a lawsuit against a popular South African cartoonist, Jonathan “Zapiro” Shapiro, his publisher and its editor over a cartoon called Lady Justice, depicting Zuma’s 2006 rape trial. Eventually, four year later, in 2012, Zuma dropped the charges.

Tackling the hypocrisy of leaders

That same year, Zapiro’s controversial piece, entitled “The Spear to be raised at Social Cohesion Summit”, inspired by a painting called The Spear by artist Brett Murray, became the subject of international attention.

The cartoon depicted Zuma’s erect penis with a showerhead and legs, accompanied by a verse. In essence, the former president’s nakedness resembled his perceived corrupt rule and lack of morals, while the shower referred to a comment Zuma made during his 2006 rape trial that showering after sexual intercourse would minimise the risk of contracting HIV. Murray’s painting was vandalised and the government called for the urgent removal of the cartoon.

It was believed that if such daring creativity was allowed to flourish, the public would begin to question their leadership and wonder whether they had elected the right leaders. This time, to his critics, Zapiro had crossed the line.

In defence of his artistic expression, Zapiro said: “My latest cartoon is meant to be scathing but humorous. It’s also serious commentary about a seriously flawed, hypocritical leader.”

And, even when his cartoons have been viewed negatively, Zapiro has carried on, receiving accolades for his work, including numerous cartoon collections.

Zimbabwe - a hardline approach

In neighbouring Zimbabwe, the response to political cartoons has been more hardline. Indeed, a cartoonist was nearly imprisoned for allegedly disrespecting the late president, Robert Mugabe.

Politically, Zimbabwe has been predominantly regarded as a one-party state, led by Mugabe, who ruled the nation for nearly four decades. Opposition parties, state critics and independent publications were all considered a threat to the state. Serious political contenders only emerged in 1999.

In 1987, during Mugabe’s reign, Tony Namate joined the state-owned Herald as an editorial cartoonist. Later, he moved to the now defunct Daily Gazette, The Independent and then the Daily News, all considered to be opposed to the state, where his cartooning style flourished. While there, he dared to speak truth to power. “Political cartoons have encouraged political debate and opening up of views among a nation that was afraid to express itself,” Namate tells Aljazeera Journalism Review.

For the past three decades, his political cartoons have driven political debate in Zimbabwe and beyond. His daring pieces have graced most prominent local and many international publications. The popular cartoons have become a form of freedom of expression.

An ambiguous art

“Cartoons are ambiguous. They can say one thing but mean another. It’s up to the reader to interpret the way they see it. It can criticise indirectly. It is less threatening but still effective. It’s difficult to prosecute,” says Namate.

Namate’s influence cannot be understated. Many of his cartoons have drawn global attention, particularly one he did in 1998 of Mugabe, who was incensed by the cartoon. Unlike Zuma, Mugabe did not file a lawsuit, instead Namate came close to being imprisoned.

“It was a cartoon that I did after Mobutu had fled Kabila’s forces in then Zaire, now DRC,” Namate recalled. “It showed a newspaper headline - Mobutu Flees - with the caption ‘Today’s headline’ and in the next panel was a newspaper headline - Mugabe Flees - with the caption, ‘Tomorrow's headline?’”

Political cartoons have encouraged political debate and opening up of views among a nation that was afraid to express itself

Tony Namate, political cartoonist

Mugabe’s reaction revealed how politicians, particularly those unpopular among their subjects, viewed critics questioning their reign and their growing fear of an uprising. A year earlier, in 1997, Zimbabwe’s economy had taken a huge hammering, after billions of unbudgeted payouts were paid to war veterans to appease their mounting revolt against Mugabe’s leadership. Besides, the comparison with Mobutu, a known former African dictator, who ruled Zaire for decades, enraged Mugabe.

But while Namate faced a political backlash, some from the dominant ruling party had always sympathised with him and that gave him the courage to continue. “I have received a lot of encouragement from across the board, including from ruling party supporters. Some negative comments come from politicians or members of the ruling party. Positive comments are mostly in the form of encouragement,” he says.

After three decades as a cartoonist, Namate retired, however his plans were interrupted and, after four years, he is now back. “I retired in 2018 to do full-time horticulture on my plot. Since then I have been under pressure to contribute my analysis through cartoons on the worsening political situation in the country,” he says. “I came out of retirement about four months ago after persistent pressure from Zimbabweans.”

From his decades of experience, Namate reveals the secret of a great cartoonist. “Avoid using emotion in your work whenever possible. It makes it personal. Cartoons need to stand on their own, they must take on a life of their own.”

Speaking truth to power

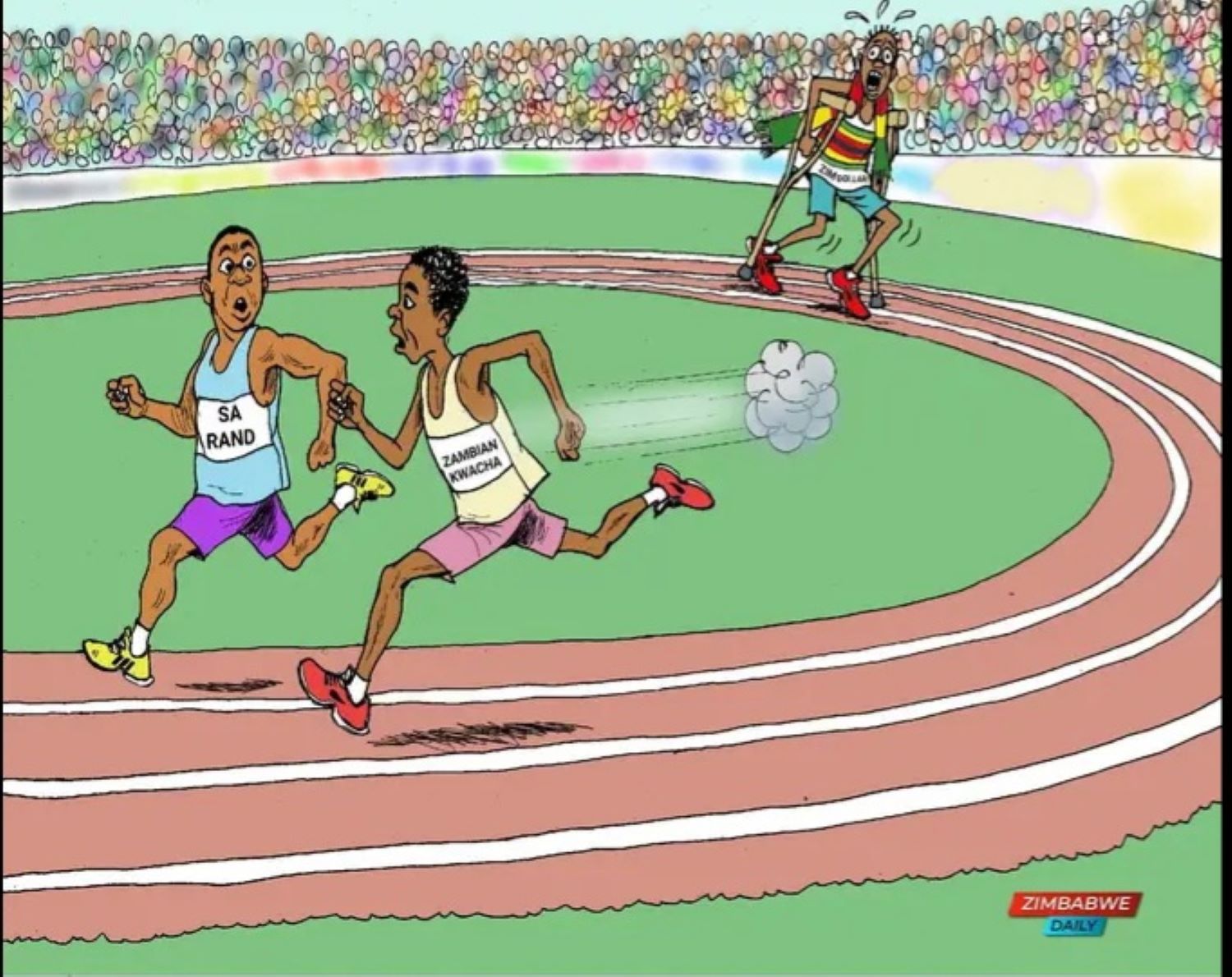

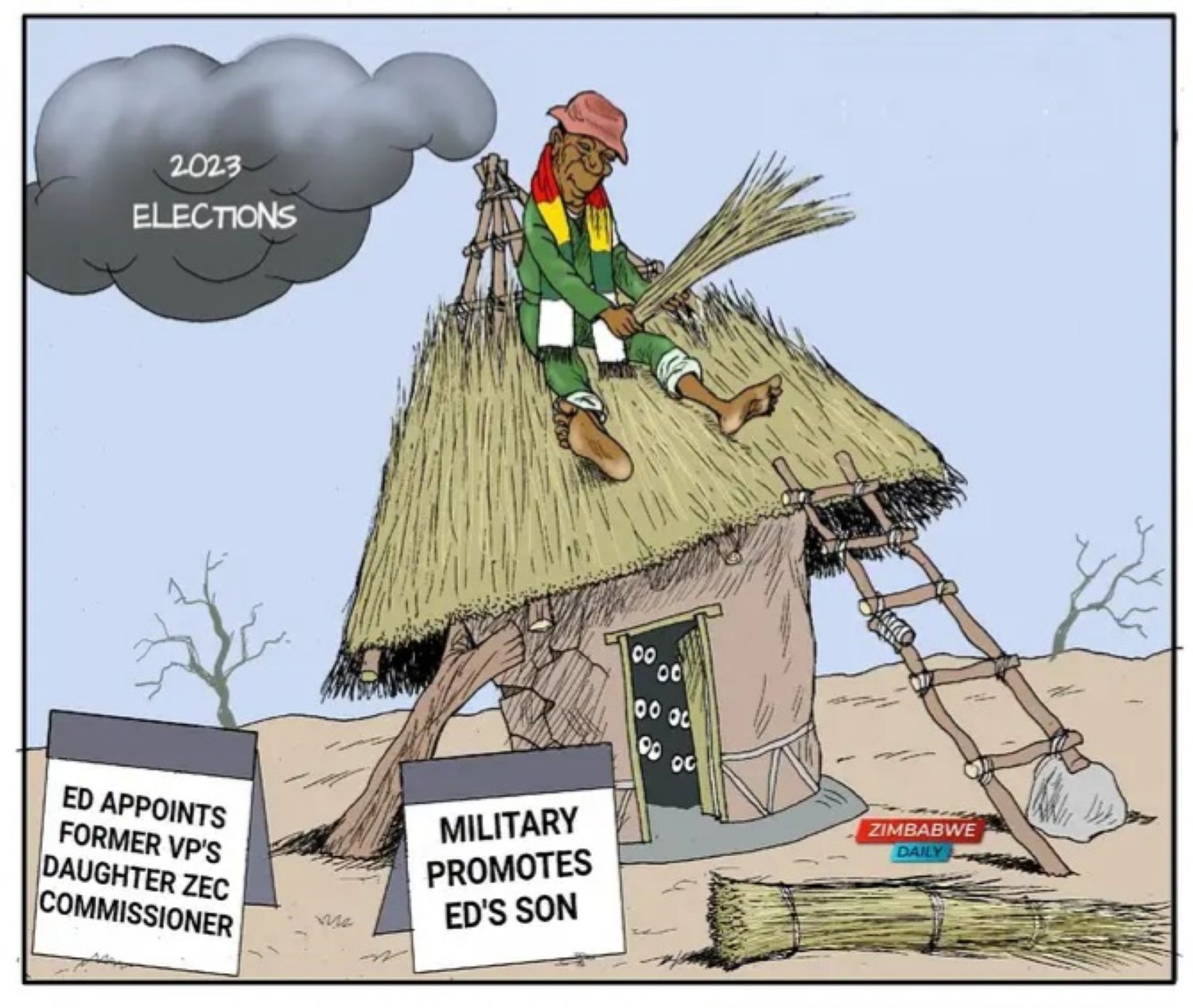

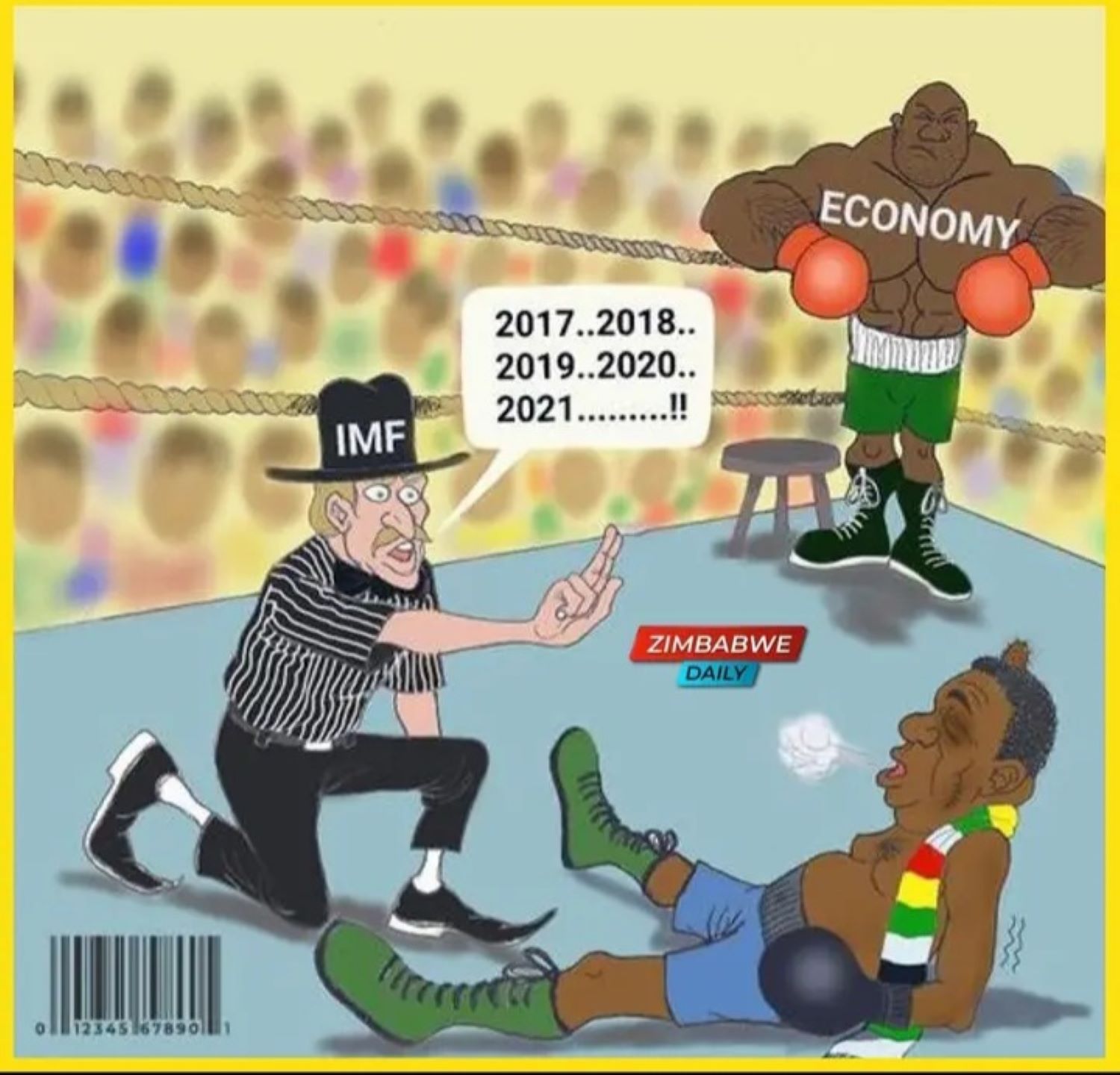

With the appearance of new cartoonists, with thought-provoking, hard hitting pieces aimed at the political elite, such as those published by the Zimbabwe Daily, the seeds of speaking truth to power, sowed by the likes of Namate, have become highly visible in the country.

“Globally, cartoon trends are changing, moving from the inside pages to the front page and that’s what the Zimbabwe Daily is driving towards, making our social commentary via caricature,” Yvonne Muchaka, the Zimbabwe Daily editor, tells Aljazeera Journalism Review. “We are giving the reader an opportunity to make derivations from their own observations and experiences with individuals, policies or hard issues. Our cartoons have provoked conversations on all platforms they are shared on and people get to express themselves on the given topic.”

To avoid lawsuits, their cartoons, according to Muchaka, summarise what people are experiencing in the country. With this, they easily grab people’s attention and spark robust conversations. The caricatures mainly zero in on elections, political intolerance and the economy, among other trending themes.

One is able to say a million things without uttering a word

Yvonne Muchaka, Zimbabwe Daily editor

“As you may know, political discourse in Zimbabwe has been made unattractive, dangerous and one can easily land in trouble with the state. So, what we have done is to summarise the general feeling of the public and portray those in a cartoon format. The general person is too busy hustling to stop for a read.”

With many people focusing on making ends meet, cartoons are a quick, easy way to capture their attention. “In cartoon format, people begin to think and interpret the cartoons in their minds, form an opinion and gain a lasting impression that causes the individual to share their thoughts without necessarily sharing it,” Muchaka says. “Because it is humorous and thought provoking at the same time, it allows for one major subject to be spread far and wide through social media statuses without necessarily ‘talking about it’.”

Besides initiating debates on trending issues, such as the faltering economy, the Zimbabwe Daily cartoons “seek to hold those in power to account. The exaggerated comic effect is just like what zoom is to videography or lighting is to theatre, creating an ambiance and focusing the mind on a critical issue and this component of the creative arts must be kept alive by all means, no matter the advancements in technology,” says Muchaka.

Freedom of expression

Muchaka agrees with Namate on freedom of expression, adding that: “Caricature is open to multiple interpretations and at Zimbabwe Daily, we strive to encourage public discourse through our imagery and we seek to invoke the readers’ minds without necessarily ‘talking’ to them. So, one is able to say a million things without uttering a word.”

Due in part to its cartoons, which help explain things in simple terms, the publication is now popular with online readers. “Our readers look forward to our cartoons. We have managed to endear ourselves in the minds of our followers because of the popular narrative. At times, we not only focus on what people are going through, at times we want to draw the attention of the people to what would be happening around them and what it means.”

By using simple drawings that help simplify complex issues, the cartoons can communicate directly to the layman. “Recently, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) announced steep fees for electoral participants. We had to interpret the meaning of such pronouncements to the ordinary person and portray it for the layman in politics and this has generated interest around an issue otherwise reserved for the candidates,” Muchaka says.

Before Namate, who says he prefers “a sketchy style that uses wit to stress a point,” retires for good, he will bequeath the art into safe hands. “I had a Cartoon Club in the early 90s where I taught several young artists, among them Wellington Musapenda and Knowledge Gunda and both do cartoons for the state-owned Zimpapers stable,” he says.