The Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982 saw over 3,000 unarmed Palestinian refugees brutally killed by Phalangist militias under the facilitation of Israeli forces. As the first journalist to enter the camps, Japanese journalist Ryuichi Hirokawa provides a harrowing first-hand account of the atrocity amid a media blackout. His testimony highlights the power of bearing witness to a war crime and contrasts the past Israeli public outcry with today’s silence over the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Caution: This article contains a graphic image at the end

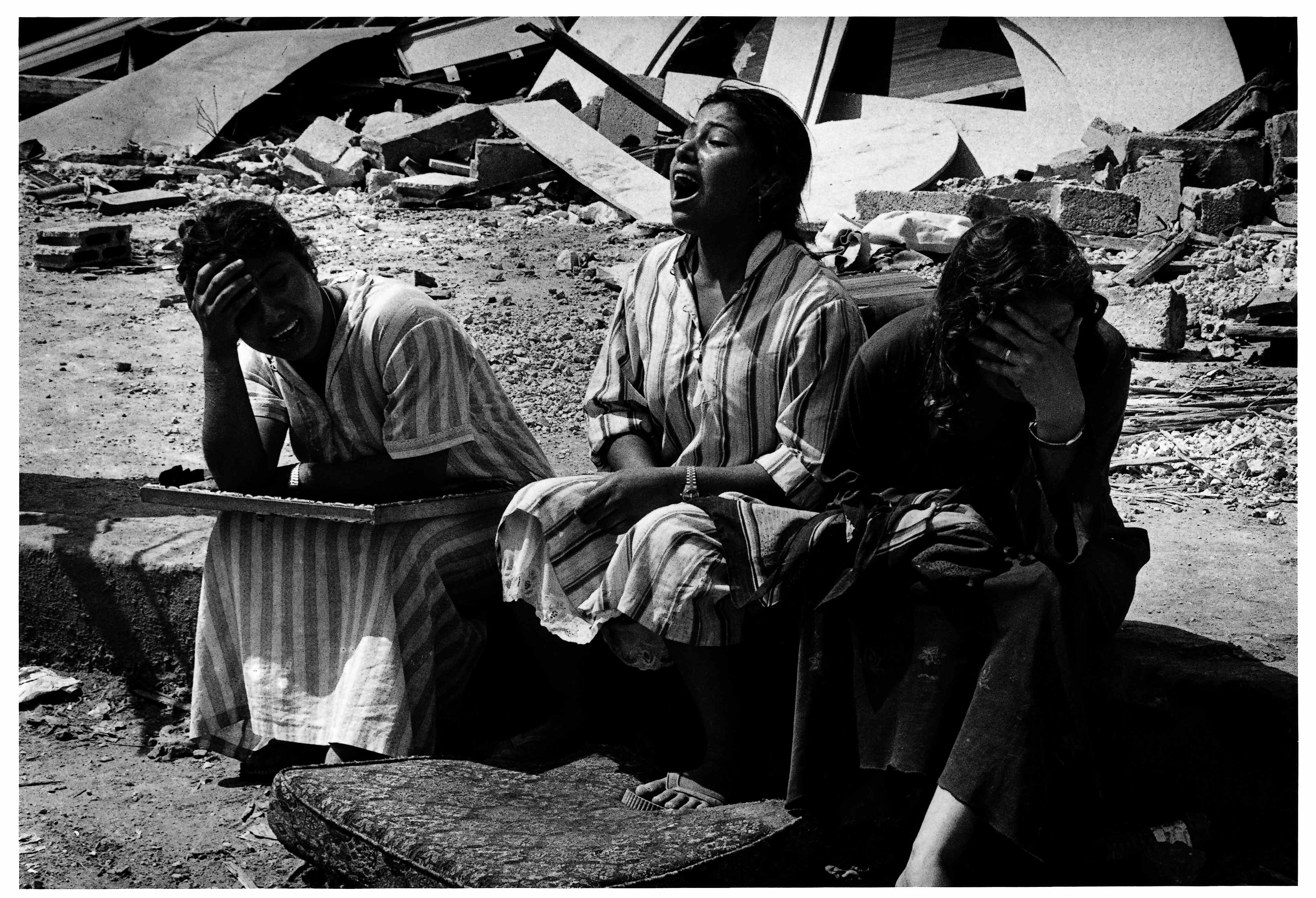

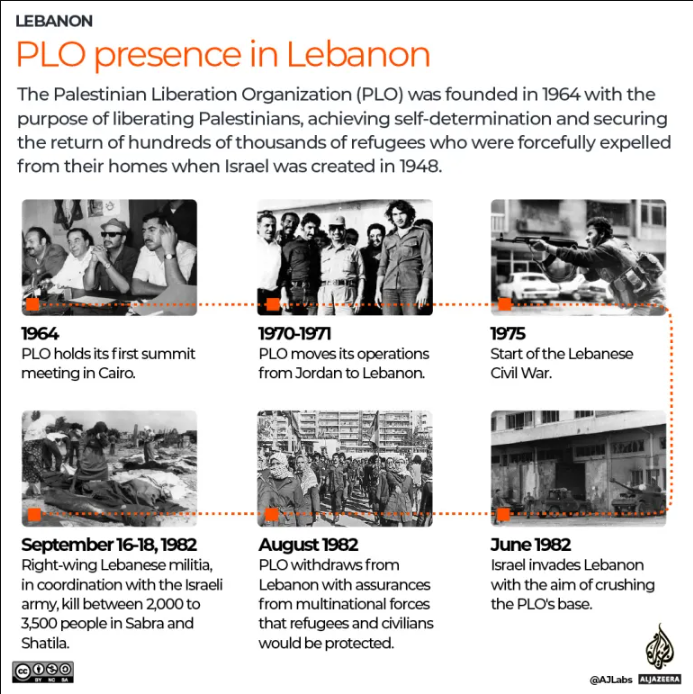

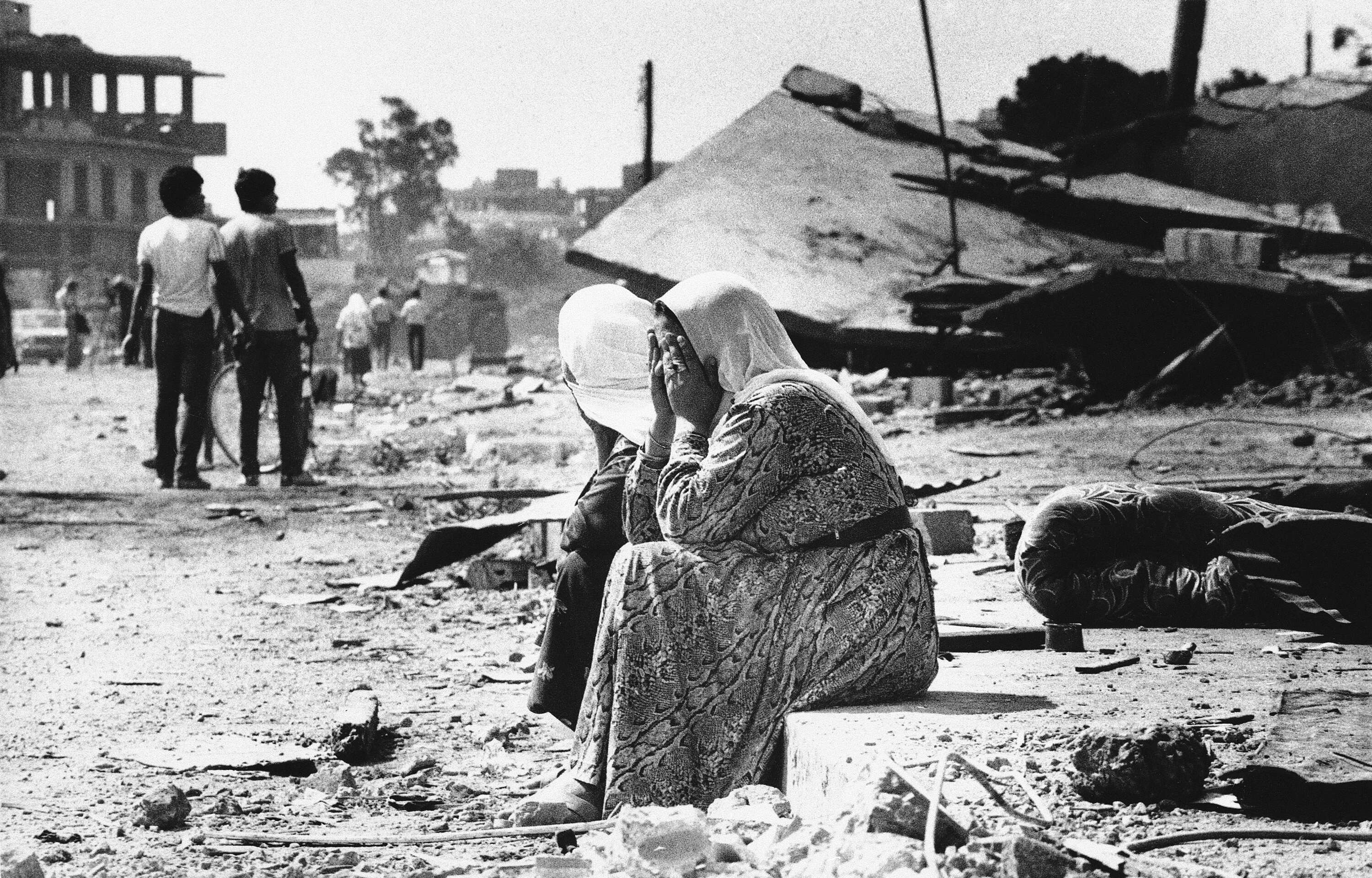

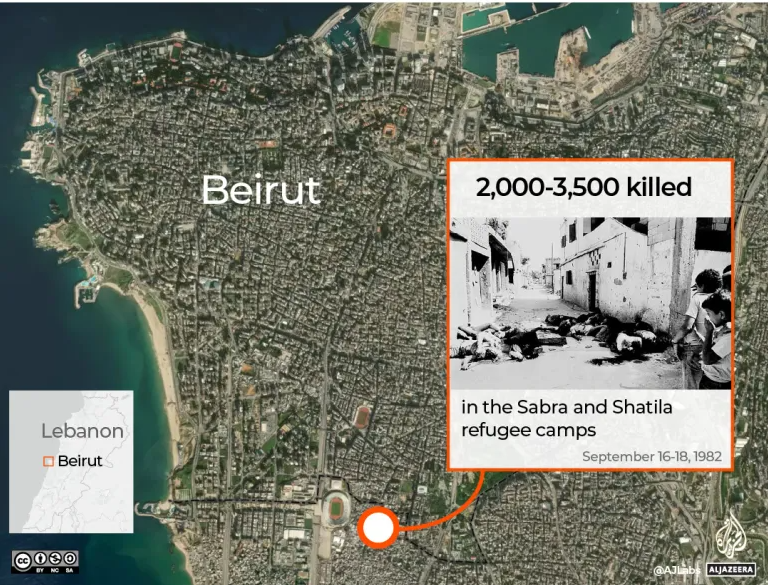

On September 18, 1982, the world was jolted awake by horrific images of a massacre trickling out of the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps in West Beirut, Lebanon. Over the course of three days, a gruesome massacre unfolded under a media blackout. From September 16 to 18, between 2,000 and 3,500 unarmed Palestinian refugees were brutally murdered.

Israeli forces, commanded by then Defence Minister Ariel Sharon, surrounded the camps and facilitated the entry of the Lebanese Phalangist militias—a right-wing Christian paramilitary group—into the camp to massacre the Palestinian refugees. The Phalangists’ attack was claimed to be a vengeful response to the assassination of their leader and newly appointed President of Lebanon, Bashir Gemayel, which later turned out to be by Habib Shartouni, a fellow Maronite Christian.

The victims were predominantly the elderly, women, and children left behind after the Palestinian fighters had been evacuated as part of a Philip Habib ceasefire agreement brokered between Yasser Arafat, the Syrian government, and Israel. Over 10,000 PLO members were evacuated from Beirut starting on August 21, 1982, in compliance with this agreement. West Beirut was under complete Israeli siege during this time, with telecommunications severed and movement severely restricted.

Among the first witnesses to the aftermath of this atrocity was Japanese photojournalist Ryuichi Hirokawa. Forty-two years later, Hirokawa (now 82 years old) recounts his harrowing experience entering Sabra and Shatila during the final hours of the massacre, providing a rare and chilling account of one of the most brutal episodes in modern Middle Eastern history.

Entering the Inferno: Hirokawa’s Journey to Beirut

Hirokawa’s journey to Lebanon began in late August 1982, following reports of escalating violence and unrest. He arrived in Lebanon at the end of August 1982, travelling through Syria and the Beqaa Valley. Along the way, he encountered many members of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) evacuating from Beirut to Syria. “I talked to them and interviewed them,” he recalls. “When I reached Beirut, there were still some PLO members who hadn’t left yet, and I interviewed them too.”

At night, from where I was staying, we would see flares lighting up the skies above the camp and hear continuous gunfire. It was not the sound of crossfire, but rather one-sided shooting, and this gave me a terrible feeling about what was happening inside the camp

As the evacuation neared its final days, a German friend working as a volunteer medic with the Palestinian Red Crescent expressed concerns for their safety. Hirokawa escorted this friend back to the Beqaa Valley to join the evacuation to Syria. Upon returning to Beirut, Hirokawa found the city under complete Israeli siege. Using his knowledge of Hebrew, he navigated the Israeli and Phalangist checkpoints and managed to re-enter West Beirut. The atmosphere in the city was tense and foreboding. “At night, from where I was staying, we would see flares lighting up the skies above the camp and hear continuous gunfire. It was not the sound of crossfire, but rather one-sided shooting, and this gave me a terrible feeling about what was happening inside the camp.”

A Lone Witness to Atrocity

On the early morning September 18, Hirokawa felt compelled to investigate the situation in Sabra and Shatila camps, located adjacent to each other in southern Beirut. “I knew something terrible was happening, and I wanted to go to the camps to see for myself. It didn’t feel safe to go alone, so I asked other journalists to join me, but most refused, saying it was too dangerous,” he says. Undeterred, Hirokawa decided to go alone, prepared to turn back if he was denied entry.

It felt like I had walked into a crime scene, and I knew it was dangerous to stay, so I decided to leave quickly before being noticed

“I first attempted to enter from the main entrance of Sabra, but it was blocked by an Israeli tank,” Hirokawa recounts. “I showed my press card and camera, but the soldier wouldn’t let me pass. So, I circled the camp, searching for another way in.” Eventually, Hirokawa found a small opening near a bridge on the southern side of the camp. He climbed over a barrier and entered through a narrow alley into the camp. “The first thing I saw when I landed was the body of an old man lying dead on the ground,” he says. “I could still hear distant gunshots. It felt like I had walked into a crime scene, and I knew it was dangerous to stay, so I decided to leave quickly before being noticed.”

Hirokawa continued along the camp’s southern edge, where the landscape was reduced to rubble. Amidst the destruction, he hesitated, weighing the risks of venturing further. “As I was deciding whether to proceed, I saw water gushing from a broken pipeline damaged by an explosion,” he recalls.

Bearing Witness: The First Report of the Massacre

The massacre was supposed to have ended before noon on September 18, and Hirokawa estimates he entered the camp during its final hours. “At first, I didn’t see a single living person—just bodies strewn on the ground,” he recounts. “Eventually, people who had been hiding emerged when they heard there was a foreigner. I had left my hotel at 8 a.m. and entered the camp around 9 a.m. The Red Cross arrived and were allowed in around noon, and other journalists followed at around 1 p.m.”

Hirokawa continued to navigate the camp, witnessing the aftermath of a massacre that had left entire families slaughtered. “I saw about 50 bodies,” he says. “There were no living people in sight in the initial hour, only the dead lying in the open.” As he ventured deeper, a few survivors cautiously emerged from their hiding places, drawn by the sight of a foreigner. As Hirokawa cautiously navigated the devastated camp, he eventually encountered two French journalists who had also managed to enter. The atmosphere was heavy with shock and disbelief, and the journalists exchanged only a few brief words of shock, before moving on, each absorbed in documenting the horrors they were witnessing. The sheer scale of the massacre left little room for conversation; the focus was solely on capturing the grim reality unfolding before them. As more journalists arrived, he felt his role there was complete.

The Media Blackout

Despite the scale of the atrocity, there was a complete media blackout in the initial hours. Communications in West Beirut had been severed by Israeli forces, preventing journalists from transmitting their reports.

“I went back to my hotel to inform the wires and the Japanese media about what I had seen,” he explains, “however, with all communication lines cut by Israel, news of the massacre did not break until after 3:00 p.m.” The BBC was the first to broadcast the news, thanks to an unexpected advantage. “I asked the BBC staff how they managed to transmit their information,” Hirokawa says. “They told me that Israel was occupying the country and had the only working communication line to the outside world. They managed to use Israel’s military communication line to send their report.”

Hirokawa was one of the first to enter the camp, with no official permission granted. “No one allowed us in; I only got in because I found my own way,” he says. For a couple of hours, he was alone, documenting the massacre before any other journalists were allowed in. “Many journalists wanted to report on what had happened, but Israel’s complete control over communications made it nearly impossible.”

“There were no living people in sight in the initial hour, only the dead lying in the open.” As he ventured deeper, a few survivors cautiously emerged from their hiding places, drawn by the sight of a foreigner.

A Society in Shock: The Israeli Response

The news of the massacre sparked a wave of outrage within Israeli society, leading to mass protests and a public reckoning. The Israeli public, particularly those from left-leaning groups and political parties that supported a two-state solution or some form of coexistence, took to the streets, condemning the actions of the government and demanding accountability. “These protests were driven by a realization that right-wing politicians’ promises of peace were false,” Hirokawa reflects. This public pressure led to Ariel Sharon’s removal from his post as Defence Minister, following an investigation that found him “indirectly” responsible for the massacre. This marked one of the rare instances in Israeli history where public outcry had a direct and significant impact on military and political decisions, underscoring the power of civic action in holding leaders accountable for their roles in wartime atrocities.

Gaza Today: A Stark Contrast

Reflecting on the present, Hirokawa draws comparisons between the public response to Sabra and Shatila massacre and the current lack of opposition to the ongoing genocide in Gaza. “Today, the voices of dissent are far more muted,” he observes. “Right after October 7, I tried to enter Gaza to no avail. While there waiting for the Israeli government to grant us permits to enter the Gaza Strip, I visited a kibbutz on its outskirts and spoke to its settlers who were taken hostage during the Hamas attack. Some witnesses recounted how the Israeli army, in its aggressive response, ended up killing both Palestinians and fellow Jews.”

According to Hirokawa, many of those living in the kibbutzim near Gaza had once advocated for coexistence with Palestinians. However, following the events of October 7 and the ensuing hostilities, such voices have been largely silenced. “The tragedy is that those who once believed in peace are now drowned out by fear and anger,” he laments and adds, “Israel’s society has shifted significantly to the right.”

The Sabra and Shatila massacre remain one of the darkest chapters in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a brutal reminder of the devastating impact of unchecked violence. Ryuichi Hirokawa’s testimony serves as a stark reminder of the power of journalism to bear witness to atrocities and to challenge the narratives shaped by those in power. Four decades later, as we witness another genocide, his words resonate as a call to remember, to document, and to never forget the human cost of war. Hirokawa’s testimony is a powerful reminder of the critical role of journalism in bearing witness to atrocities and holding power to account, even when the world looks away.

(The interview with Ryuichi Hirokawa was conducted over the phone and a communication app in Japanese by the author.)

Palestinian women point at a poster depicting Palestinians who were killed during the Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982, to mark the 28th anniversary of the massacre in Beirut, September 16, 2010. REUTERS/ Sharif Karim (LEBANON )