The recent takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban shines a light on the often exploitative relationship between Western foreign correspondents and the Afghan ‘fixers’ they leave behind.

The sudden takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban on August 15 turned the country into a hunting ground for the media worker overnight. While some journalists and media workers have managed to leave Afghanistan - often by appealing for help from their Western counterparts with whom they have worked - many have turned to work as street vendors or at restaurants instead to feed their family. Others are living in hiding.

Media freedom was considered one of the biggest achievements of the past two decades in Afghanistan, and the Afghan government vowed to protect these gains as well as women’s rights to work and education.

However, since the fall of Kabul, the media has come under severe threat. More than 150 Afghan media outlets have already closed due to fear of intimidation from the Taliban and for lack of funding. Once a flourishing sector in post 9/11 Afghanistan, the media is slowly dwindling.

Many Afghan journalists have been beaten and jailed since the Taliban took control of the capital. Of these, many are the so-called “fixers” and interpreters who worked alongside foreign journalists covering events in the country for their news organisations back home.

The media has come under severe threat in Afghanistan - more than 150 outlets have closed

Many Western journalists reach acclaim in the distant and conflict-ridden lands they cover, but it is the local people who help them collect their information or speak for them with the native informants and interpret the local languages who enable them to do that.

The work of “fixers” - who are for the most part professional journalists themselves - often goes overlooked and unremarked. Yet they speak of the “impotence of journalists who don’t properly speak the language of those they are reporting about” and who, without their work, would not be able to report at all.

It’s not only about comprehending a few words and sentences but about connecting with another person to empathise - something that can often only be done through their mother tongue. As one interpreter who didn’t want to give his name for fear of reprisals because of his work with foreign journalists told me: “Most people will share and tell their story in depth if one has made an effort to get into their world by genuinely speaking with them in their language.”

'Now he hangs up the phone on me'

It is a tale familiar to many who work as fixers or interpreters for foreign journalists in Afghanistan. Afghan interpreters and fixers are the ones bringing the flavour and often the context to the stories foreign journalists cover in the country. But, once the foreign journalist’s assignment is complete and they leave the country, they rarely respond to the local colleagues they hired as “interpreters and fixers” even as they are faced with violence or death.

One Afghan fixer and interpreter - who does not wish to be named - who worked with prominent foreign journalists recalls one he was working who liked to tell everyone that he had converted to Islam. “I was happy at first [to hear this], but then I later realised he was just trying to get closer to people. Sometimes he would call me and talk for hours or ask me to collect information. But now he just hangs up the the phone without with replying to my messages.”

Bismillah Pashtunmal, who runs a media services company providing fixing, translation, transcribing, videos and photos for foreign journalists, says: “When the Afghan government lost control in much of the south of Afghanistan, I sent a message to one of the foreign journalists I worked with and asked him what he could do for my evacuation out of Afghanistan in these critical times? He read the message, ignored it and didn't reply.”

“I asked so many of the prominent journalists that I had worked with, but only a few helped me, To whom I am very thankful,” adds Tahmeena*, 29, a freelance journalist and fixer in Afghanistan who did not want to give her real name. “Some really thought it was safe for me to stay in Afghanistan. Maybe they do not check the news, or they live on the moon.”

Tahmeena started her career in Journalism in 2012, and she also collaborated with many foreign journalists as an “interpreter and fixer”, but she knew her career was over when the Taliban entered Kabul.

Leaving everyone and everything behind, she just managed to get to Kabul airport - and get out of the country - a day before the IS-K carried out a suicide bombing that killed more than 200 people.

He told me he would hang me in the town square

Many Afghan journalists have been harrassed and assaulted for doing their job. Foreign journalists, by contrast, have had a completely different experience with the Taliban. But few speak up about this double standard. One who has is journalist Matthieu Aikins who writes for NYT Magazine, the New York Times’ Sunday magazine. He wrote on Twitter: “To be fair, as a foreign journalist, I have been mostly treated with courtesy by Taliban officials in Kabul over the past few weeks. I appreciate the steps @Zabehulah_M33 has taken for our safety. But we cannot accept a double standard for local journalists.”

The Taliban is known for referring to all Afghan journalists as “hired mouthpieces” for the previous administration and for the US. Recently, after publishing news of the Taliban conducting house searches, one journalist was reportedly summoned by the deputy governor of the Taliban and told: “He would hang me in the town square.”

Sami Mehdi, a prominent Afghan journalist, notes that for the Taliban, the media “has been a tool to propagandise against the mujahedin and call them Pakistanis and Punjabis in order to serve the interests of occupiers.

“A hired journalist is more dangerous than a hundred Arbaki (Local Police/Paramilitary). I doubt the faith of those who restrain from killing journalists. Kill the rented journalists. Control the media,” wrote the chancellor of Kabul University, who was appointed days after the fall of Kabul.

During the second half of 2021, following his Tweet, more than 10 local journalists were killed in Afghanistan.

'Forgotten'

The Taliban justify this assault on journalists by labelling them “spies”, but this is nothing new. Journalists seen to be working alongside foreign news organisations have been targets for decades - not just from the Taliban, but also from criminals targetting them for their perceived “wealth” as “agents of the West”.

“There are always threats and dangers while we are working with foreigners in Afghanistan - robbing, kidnapping and even killing by armed groups and criminals,” says Bismillah Pashtunmal. Many have been “arrested by the local authorities, tortured, abused, prosecuted, and facing accusations”.

But the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan has not only put the lives of those involved with the media industry over the last 20 years in danger, it has also robbed them of the opportunity to frame the narratives coming out of Afghanistan. This is because they can no longer freely work alongside foreign correspondents and thus ensure that the reporting coming out of Afghanistan is accurate and that it reflects reality for Afghans themselves. “For me, as an Afghan journalist, it’s now even more challenging to ensure that our foreign colleagues aren’t distorting the narrative,” explains Tahmeena.

Like many Afghan media workers, Tahmeena believes that many foreign journalists who spent time in Kabul after the Taliban takeover have been - intentionally or unintentionally - trying to normalise what’s happening in Afghanistan.

Many local media workers have been arrested by the authorities, tortured, abused, prosecuted, and facing accusations

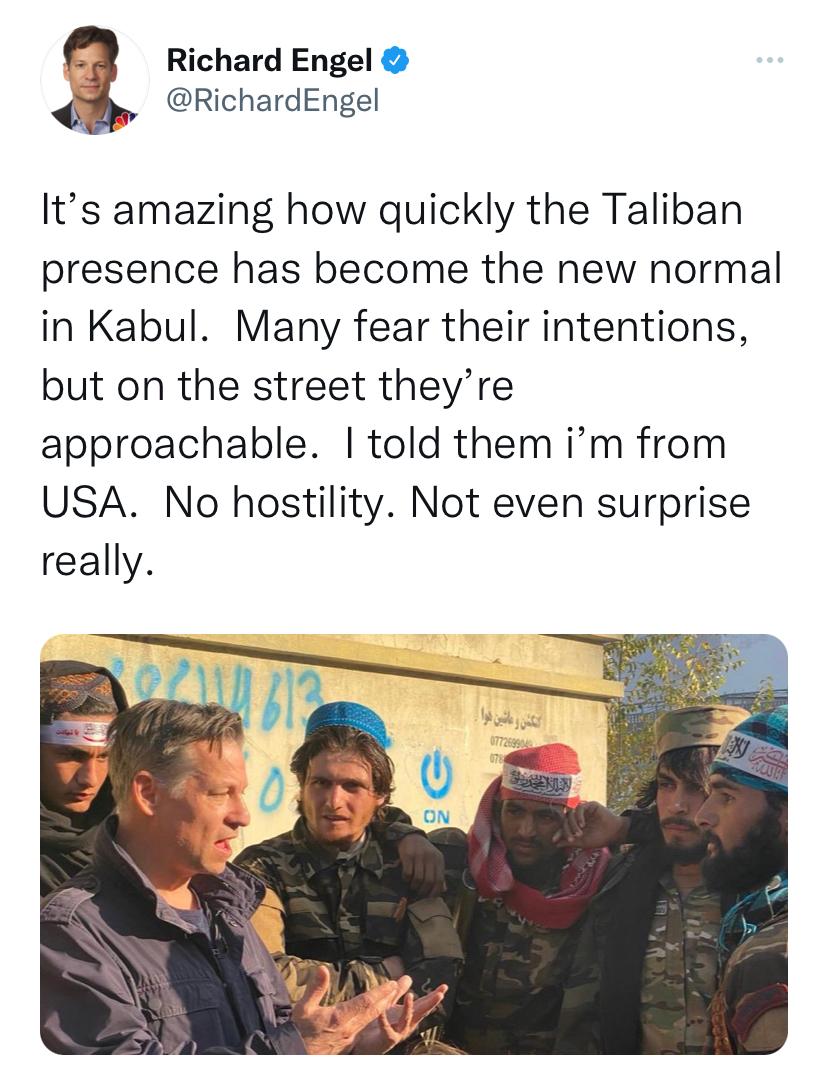

For example, Richard Engel from CNBC Tweeted in November: “It’s amazing how quickly the Taliban presence has become the new normal in Kabul. Many fear their intentions, but on the street they’re approachable. I told them I’m from USA. No hostility. Not even surprise really.”

Another foreign journalist, Jake Simkin who covers Afghanistan for the New York Post, responded: “I will come to your defence since the Taliban has treated me as a journalist better than during the Republic. I travelled the whole country now. The Taliban are learning, it is a long road for them, but they have given respect to foreigners and Afghans. They do take in what we say.”

During her visit to Herat, Jane Ferguson, a foreign correspondent for PBS, Tweeted: “Surreal experience visiting the #Herat citadel today. The several groups of other visitors were all #Taliban fighters. These guys were from #Helmand and had never been to the city before, so came for a vacation. They approached us and asked me if they could take this picture.”

But this perception, Afghan journalists say, completely fails to acknowledge that this is very far from their own experience which include arbitrary arrests and beatings, according to Human Rights Watch. They feel abandoned to their fate, they add.

The Taliban has also put tough new restrictions on local journalists. Media is prohibited from printing or broadcasting reports that “are contrary to Islam”, “insult national or religious figures”, or “distort news content” and “women should appear in Islamic Hijab”.

A copy of the regulations seen by Human Rights Watch shows that journalists are required to “ensure that their reporting is balanced” and not report on “matters that officials have not confirmed” or issues that “could have a negative impact on the public’s attitude”. Media outlets are required to “prepare detailed reports” together with the Taliban regulatory body before publication.

Putting local journalists in danger

For nearly 20 years, Bawar Media Center (originally called the Bayan-e-Shamal Media Center) was located in Mazar-i-Sharif, a city in northern Afghanistan, and was founded in 2003, just shortly after the arrival of the NATO forces in Afghanistan.

On its LinkedIn profile, Bawar Media Center describes itself as “A media center to inspire Afghan lives for positive change.” It states: “BMC is a professional media centre dedicated towards provision of innovative, quality and fast media services to our clients. We are committed to a professional working environment, professional staff and proficient communication to be highly effective in the fast-moving media business in the market.”

More than 60 men and women were recruited to work at the Center, producing positive stories about the Afghan government and its security forces. The Bundeswehr (German Ministry of Defence) helped to fund it, paying 1.6 million euros per year towards its running costs of operating radio and TV broadcasting, newspapers and magazines. The intention was to create a better understanding of the combat operations of international troops among the Afghan population.

However, the Center was frequently criticised for failing to be “culturally appropriate”. To counter the Taliban war propaganda, the Center regularly posted about successful campaigns against the Taliban on Twitter, depicting local soldiers as protectors.

Siddiqullah Tawhidi, director of the Afghan media watchdog, Nai, says efforts to counter Taliban messaging backfired. “The Allied Forces used it as a propaganda tool, but most of the time, their propaganda was also not culturally appropriate, and it failed to defy the Taliban. And on the other hand, the Taliban used their propaganda to garner local support to their cause.”

Ultimately, says Tawhidi, “the Bayan Media Center’s operations were contrary to the ethics of journalism and mass media law and media regulation in Afghanistan. And it has put the lives of those involved with the Center in grave danger”.

Marwa, a mother of two who does not wish to give her full name, is one of the many people who worked with BMC, opted for the job because of the high salary it was paying. But since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, she has been forced to change her location several times to protect herself and her family until she was finally evacuated to Germany late last year.

One of her colleagues, Ahmad Shah*, 35 and a father of two, (name changed for security reasons), however, is still in Afghanistan and trying desperately to get out of the country. He worked for the Center for nine years as a graphic designer.

Shah says he waited at the airport for several days after the Taliban took control of Kabul, but was unable to get out. “After an unsuccessful attempt to get into Kabul Airport and flee the country, I am on the run constantly,” he says now.

He has good reason, says Tahmeena. “I was called infidel just because I worked with foreign journalists. I expected them to support us - we Afghan journalists went through a lot and supported our fellow journalists - now is the time for them to contribute.

It might be just an assignment for a foreign journalist, but it’s our life, story and history for us

“Maintaining ethics in journalism in a post-conflict, war zone or in countries with totalitarian regimes is of vital importance,” she adds. “This is how we can protect individuals involved in the media industry.”

Tawhidi says: “Foreign journalists in Afghanistan should be careful that their reporting and involvement with locals does not put their local colleagues in a precarious situation, and they should always try to protect their local colleagues. In Afghanistan, we have seen that when foreign journalists are kidnapped, they have been released, but their local colleagues (fixers and translators) are generally killed, as was the case with Ajmal Naqshbandi. Foreign news organisations must protect their local colleagues and take responsibility for them”.

Pashtunmal strongly agrees. “I want the foreign journalists and their organisations not to forget their local aides while trapped in these dangers; local journalists are the main victims of violence and have nowhere to go and no one to support and protect them.”

Most Afghan media workers who enjoyed freedom in the last two decades have either left Afghanistan or are in hiding. But many of those who have left still hope they will return.

As Tahmeena says: “We Afghans own our stories - it might be just an assignment for a foreign journalist, but it’s our life, story and history for us.”

*Some names have been changed to protect sources’ identities