Caught between enraged protesters and aggressive police officers, journalists risked their lives to keep the world informed about the Gen–Z protests in Kenya. However, these demonstrations also exposed deeper issues regarding press freedom, highlighting a troubling aspect of Ruto’s government.

The 2024 Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders highlights a concerning trend for journalism worldwide, as it increasingly faces political pressure. In Kenya, the story is the same. The East African nation has been regarded, and rightly so, as one of the bastions of press freedom in a continent where press freedom remains elusive.

However, the ascension of William Ruto to the presidency in Kenya in 2022 marked a troubling shift for the country’s vibrant press landscape. The subsequent Gen-Z cum anti-tax protests served as a critical juncture, revealing the extent to which Ruto's government has crossed established boundaries concerning press freedom. As journalists face increasing restrictions and intimidation, the very foundation of independent reporting in Kenya is under threat, raising significant concerns about the future of free expression in the nation.

But even with the hostile environment during these protests, journalists demonstrated remarkable courage, facing tear gas, water cannons, and even live ammunition to keep the world informed about the unfolding crisis. While active street demonstrations have died down, discussions on the subject continue to thrive, particularly across various social media platforms and mainstream media outlets.

Journalists on the Frontlines

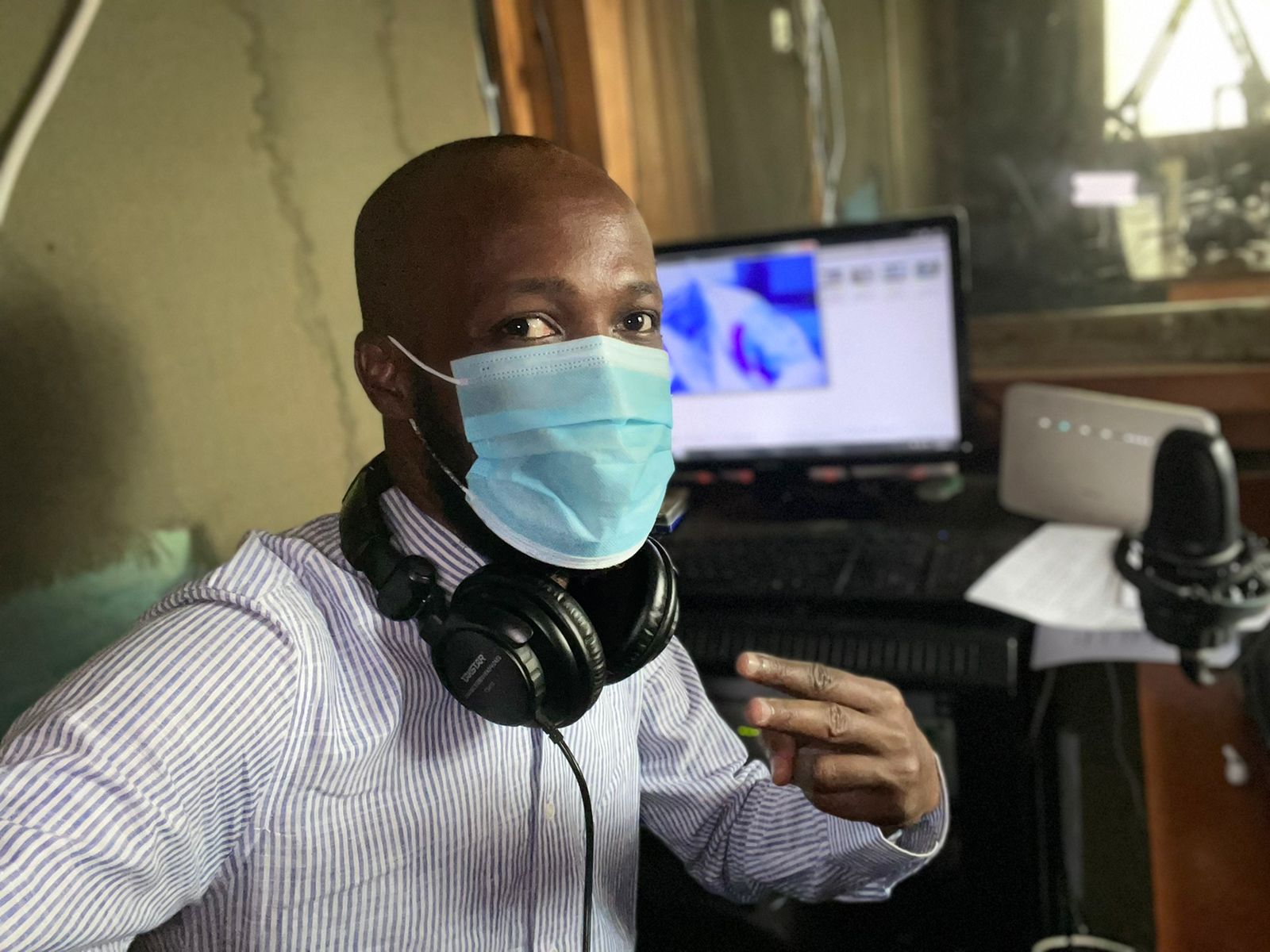

Armed with a camera and a face mask, 22-year-old Jason Maranga ventured into the streets of Nairobi, particularly Kenyatta Avenue, where thousands of Kenyans had gathered to protest against the Finance Bill. For the young photojournalist, it was his first time covering a protest of such scale.

“It was a completely new experience for me. I had never been on the ground during protests like this,” Maranga recalled, reflecting on the challenges and intensity of the moment.

He understood the risks, knowing he could easily become a target of stray tear gas canisters or live ammunition aimed at the protesters. “The streets were packed,” Maranga recalled, “and the police were very hostile towards the demonstrators.”

He described how tear gas was fired in all directions to disperse the crowd. Amid the chaos, Maranga deftly dodged the choking clouds of gas, avoided powerful streams from water cannons, and kept a watchful eye on the increasingly agitated protesters. Through it all, he skillfully captured rare, striking moments with his camera.

Although frequently engulfed in clouds of tear gas, the young photojournalist noted that police were relatively lenient toward members of the press, allowing them to approach barricades for better shots of the protesters. However, encountering the bodies of protesters marked a turning point for him, as it was his first experience with such graphic scenes. “These experiences were overwhelming and disturbed me psychologically,” he reflected.

“Covering this protest was both interesting and challenging,” said Mercy Juma Okande, former BBC News Correspondent for East Africa. The challenges she explained, lay in navigating the volatile dynamics between protesters and police while ensuring the safety of her team. Unlike Maranga, Okande has extensive experience covering similar protests across Africa and is well-versed in managing such complexities.

Before heading to the protest grounds, Okande and her team underwent “hostile environment training,” equipping them with strategies for emergencies, such as identifying exit points and knowing how to act during gunfire. “It really worked for us,” she affirmed.

One of Okande’s most impactful moments during the Gen-Z protests occurred when she saved the life of a woman who had collapsed after a tear gas canister exploded nearby in Nairobi. “I was about to go live on TV,” she recalled, “but I had to set aside my journalism hat and act as a human being when I saw this lady lying unconscious.” The woman, not a protester, was heading from the hospital back home when she was caught in the chaos. Drawing on her first-aid skills, Okande asked the surrounding protesters to step aside to allow the woman some fresh air. “She was hyperventilating, and I encouraged her to breathe normally until she recovered,” Okande recounted, emphasizing, “Humanity must come first. The story can always wait when it’s a matter of life and death.”

Covering the protests had a profound impact on Fred Kagonye’s mental health as he witnessed distressing and traumatic scenes. “I reached a point where I became numb,” he admitted. To cope with the emotional toll, Kagonye who is a journalist with Standard Newspaper, Kenya's oldest newspaper often relied on humor and conversations with colleagues about the protests, which temporarily helped him escape the horrors he had encountered. He acknowledged that therapy might be necessary, recognizing that the haunting memories could resurface in the future.

As Kagonye covered the protests, he was particularly struck like anyone by the overwhelming turnout of demonstrators on designated protest days, especially given that they were not led by any identifiable leaders. “The authorities anticipated the usual 300 to 400 people they typically see at protest marches, but the turnout was far greater," he explained to AJR.

For Okande, physical exercise and maintaining a strict separation between her work and personal life proved vital in managing the mental health challenges of covering the protests. These practices helped her stay grounded and recover from the intense experiences on the ground.

Violence Against Journalist

Journalists experienced violence especially from law enforcement during the anti-tax protests despite not actively taking part in it. Twenty-four journalists according to Kenya’s Media Council were attacked and injured by police during the demonstrations.

On August 8, CNN's Larry Madowo raised alarm on his Facebook page about targeted shootings against him and his team. “Kenyan police,” he wrote, “targeted me directly today. I was hit by a fragment after officers aimed at me and my CNN team at least twice while covering protests in Nairobi.”

Earlier incidents included the shooting and injuring of TV journalist Catherine Wanjeri along Kenyatta Avenue, despite her wearing visible press credentials. Similarly, Collins Olunga, a photojournalist with Agence France-Presse (AFP), was explicitly targeted and injured by police.

Standard Group video editor Justice Mwangi Macharia was arrested, while Sammy Kimatu, a reporter for Taifa Leo of Nation Media Group, was violently thrown out of a moving police vehicle, sustaining physical injuries. Although law enforcement denied targeting journalists, Wanjeri is adamant that her attack was not deliberate and premeditated.

These incidents of police violence against journalists during the protests highlight significant cracks in Kenya’s press freedom—an issue that has worsened under President Ruto’s administration. It also underscores the urgent need to “strengthen government-media relations,” as advocated by the Media Council of Kenya. Beyond direct assaults, journalists faced arrest and brief detentions, such as the June 18 incident in which five reporters covering the protests were taken into custody, exemplifying the heavy-handedness of Kenyan police.

The threats didn’t come solely from law enforcement. According to Kagonye, “goons” who infiltrated the protests further obstructed journalists' work. “They hurled stones at us,” he recounted, explaining that these groups were primarily focused on looting and inciting violence. “As a journalist, you find yourself caught between the police and the protesters,” he added, before asking, “Where do you run to?”

Okande acknowledges that while journalists might accidentally be caught by stray bullets or tear gas canisters during protests, intentional attacks create a sense that the press is under siege. Maranga on his part notes that the constant assaults on journalists during Gen–Z demonstrations negatively impact their work. “You can’t perform to the required standard if you are worried about your safety,” he laments. Even as journalists staged street protests against these attacks and called for justice for their brutalised peers, true accountability remains elusive.

Social Media vs Traditional Media

Social media was at the center of what is today refered to as the leaderless revolution. As discussions on the controversial Finance Bill 2024 were taking place in Parliament, Kenya's tech-savvy youths mobilized on social media platforms like TikTok and Twitter (now X) to voice their frustrations. They demanded the withdrawal of the bill, with support from AI tools such as Finance Bill GPT that also helped sustain the movement’s momentum. Hashtags like #RejectFinanceBill2024 and #RutoMustGo trended widely, leading to large-scale, often violent, street protests across the country.

Kenya’s internet penetration rate has grown rapidly, rising from 28% in 2020 to 40.8% in 2024, with 22.7 million internet users today.

Notably, 41% of Kenyans spend an average of 1 to 3 hours daily on social media. Furthermore, 80% of the population is under 35 years old, representinga significant share of the 12% unemployed population that was at the forefront of the protests. This illustrates the crucial role social media played in driving the uprising, while also underscoring the diminishing influence of traditional media in Kenya—a trend mirrored globally.

While social media proved to be a powerful tool for mobilization, it often spread unverified information, fueling violence. In contrast, traditional media played a more measured role, seeking to moderate the chaos by verifying and distinguishing facts from fiction. “The mainstream media played a crucial role in regulating social media by separating truth from misinformation during the protests,” said Dauti Kahura, a Kenyan journalist with over 30 years of experience. However, he admitted that traditional outlets had little influence on young people, who overwhelmingly relied on social media for updates.

This shift in news consumption habits reflects a broader trend. A 2024 study indicates that 77% of Kenyans relied heavily on social media for news, up from 72% in 2023. While television remains popular, print media continues to decline, with only 33% of Kenyans using it as a news source in 2024.

At the peak of the Gen-Z protests in late June, a shocking rumor began circulating online, claiming that Kenyan police had massacred 200 civilians in Githurai, a suburb about 14 km northeast of Nairobi. While some local media outlets and even the Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights were nearly duped by this fabrication, a BBC investigation ultimately confirmed that no such massacre had occurred.

Despite the questionable information circulated on social media during the protests, traditional media relied heavily on these platforms for updates, according to Kahura. “The mainstream media, just like the government, lagged behind social media in terms of information about the protest,” he noted. “Gen-Z controlled the narrative through social media, which explains why the protests endured.”

Kahura further alleged that government operatives also exploited social media to spread disinformation and weaken the protests' momentum. “The government employed a network of bloggers who propagated false information primarily to mislead the public,” he explained, comparing these tactics to propaganda methods used during the Soviet era.

In an effort to address public outrage, President Ruto turned to social media himself. On July 5th, he hosted a live discussion on X with anti-tax protesters, attracting an audience of approximately 150,000 listeners. During this session, the "hustler president," now perceived as a tax collector, apologized for the police brutality witnessed during the demonstrations.

While social media and traditional media operated almost in parallel during this period, the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA)—a civilian body tasked with monitoring police conduct—has been utilizing photos and videos from both mediums to investigate alleged police crimes. “IPOA depends on evidence obtained from the field, and it cannot be everywhere at once,” an IPOA representative explained. “At the end of the day, it relies on footage and photos captured by journalists.”

Ruto's Rise, Press Freedom's Decline

The violent treatment of journalists during the Gen-Z protests in Kenya signals a deeper, systemic issue that has escalated since President William Ruto took office. Within months of his administration, senior executives from major media organizations were dismissed, reportedly under political pressure. During the protests, the government threatened to shut down the Kenyan Television Network (KTN) after it aired footage of protesters storming Parliament. Although KTN later ceased operations citing financial constraints, it is widely believed that Kenya’s Communications Authority ordered the television signal carriers to cut off their broadcast.

Kenya’s global standing on press freedom has also deteriorated. In the 2023 World Press Freedom Index, Kenya dropped from 69th to 116th place—a significant decline. Although the country improved slightly to 102nd in 2024, Ruto’s administration continues to threaten press freedom. Journalist Kahura acknowledges that Kenya remains ahead of its neighbors in press freedom, but notes that the media environment has become precarious. Kagonye, however, sees continuity from previous administrations. “Nothing has changed much,” he said, adding, “But during Uhuru Kenyatta’s era, there were no threats to shut down media houses, unlike now under Ruto.”

The growing hostility towards the media has drawn widespread condemnation. Reporters Without Borders issued a statement denouncing the rising attacks on journalists under Ruto’s administration. “Reporters Without Borders is alarmed by the decline in press freedom in Kenya since William Ruto’s election as president, with an increase in police attacks on reporters during protests and overt government hostility towards the media,” the statement read.

Kenya’s 2010 constitution guarantees press freedom; however, over 20 acts and laws, including the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, hinder true press freedom. This act imposes penalties of up to 10 years in prison and fines of KES 40,000 ($310.49) for disseminating information deemed fake news that could incite violence.

This restrictive environment has forced many journalists to adopt self-censorship. “We practise a lot of self-censorship,” admitted Kagonye. “For obvious reasons.” He explained that being overly critical of the government can put journalists at risk. “To stay safe, you just stick to straight reporting without being too critical,” he added.

Both past and current Kenyan administrations have used various strategies to control the media. For instance, in 2017, Uhuru Kenyatta’s government ceased advertising in local commercial newspapers in favor of the government-run newspaper and online portal, MyGov, while redirecting electronic advertising to the state broadcaster. Government advertising account for roughly 30% of newspaper revenue in Kenya. Despite this shift, major newspapers like The Daily Nation and The Standard were contracted to distribute MyGov.

However, earlier in 2024, the government dropped The Daily Nation and The Standard from this contract, awarding it solely to The Star, a decision that is currently being challenged in court. Reports suggest that The Star has links to allies of President Ruto. Meanwhile, The Daily Nation and The Standard have been critical of Ruto’s administration, potentially facing repercussions. For instance, The Daily Nation launched a weekly investigative series titled "Broken Series," scrutinizing Ruto’s government, but the series was later discontinued.

Financial Pressures and Media Compliance

Before awarding The Star the contract to distribute MyGov, the Kenyan government had accumulated a debt of approximately 2,190,072,250 KES ($17 million) to media houses for their advertising services. This debt is allegedly used as leverage to suppress critical reporting. “The government has been using the money they owe private media entities as a bargaining chip to stifle dissent,” Kagonye explained. Kenya’s challenging economic conditions leave media organizations with little choice but to comply with government demands, albeit reluctantly. “At the end of the day, these media organizations are businesses that need to generate revenue—and why not profit?” he added.

The financial struggles of media organizations in Kenya reflect a broader economic landscape that was also a contributing factor to the Gen-Z protests. Before coming to power, the previous administration, in which Ruto served as deputy president, had ballooned Kenya’s public debt from 1.89 trillion KES ($21.95 billion) in 2013 to 8.59 trillion KES ($71.85 billion) by 2022. Ruto therefore wanted to raise an additional 347.8 billion KES ($2.7 billion) to reduce state borrowing and address fiscal gaps through his unpopular finance bill. For many Kenyans, however, these measures were a step too far.

Kenya's position in the 2024 Economic Indicator Index of press freedom published by Reporters Without Borders is concerning, as it has dropped from 121st place with a score of 40.52 in 2023 to 127th place with a score of 37.04 in 2024, globally.

When asked if Kenyan journalists are financially free, Kagonye gave an emphatic response: “The answer is a big NO.” He elaborated that journalists in Kenya are poorly compensated, which negatively impacts the quality of their work. While journalists earn an average of 2,124,400 KES ($16,490) annually, actual salaries vary. The lowest earners make about 1,041,900 KES ($8,087), while the highest earners receive up to 3,312,100 KES ($25,709). However, Kagonye noted that most urban journalists earn between 38,648 KES ($300) and 45,089 KES ($350) per month, barely enough to cover basic needs.

Media organizations are also struggling financially. The Standard Group, which owns The Standard newspaper, reported a pre-tax loss of 147 million KES ($900,000) in the first half of 2023 and delayed paying its journalists for several months. Similarly, Nation Media Group, which owns The Daily Nation, saw a staggering 98.8% decline in profits during the same period and issued a profit warning, predicting over a 25% drop in annual earnings for 2023. In 2024, the company laid off 180 employees, including senior editors.

Meager and irregular salaries have made journalists vulnerable to bribes. “Some journalists go for over four months without receiving a salary from their employers,” Kahura explained. “They will do anything to survive.” As a result, many Kenyan journalists are leaving the profession to pursue better-paying roles in public relations or non-governmental organizations.

Targeting Journalists and Escalating Violence

In March 2023, Ruto’s government established the Operation Support Unit, tasked with suppressing dissent during protests and targeting “nosy journalists.” Members of the unit often operate undercover, sometimes posing as journalists to arrest reporters.

The violence against journalists has not been limited to harassment. In October 2022, Pakistani journalist Arshad Sharif was killed by Kenyan police in Nairobi after failing to stop at a checkpoint. Despite mounting violence, Kenyan government and police officials continue to dismiss such incidents. Japhet Koome, a police official, once referred to attacks on journalists as merely "occupational hazards" of the media profession.

Kenyans as the Ultimate “Losers”

Upon ascending to Kenya's presidency, Ruto positioned himself as a sort of Robin Hood, presenting himself as a champion for the underprivileged. However, reality soon set in, forcing him to make a significant U-turn and attempted to impose taxes on the very underprivileged people he had initially sought to protect

Although his controversial Finance Bill has been withdrawn, many believe that Kenyans are the ultimate losers. This sentiment arises from Ruto’s decision to integrate members of the opposition into his new administration after dismissing his previous government. “Who will hold the government accountable now that the opposition is part of it?” Maranga asks, his disappointment evident. “It has become clear that politicians do not fight for anyone but themselves,” Kagonye adds.

Besides, the withdrawal of this bill came at a significant cost, resulting in the loss of 41 lives during the protests that began on June 18.

While the fight against Ruto’s Finance Bill has ended in victory, the broader battle to end impunity against journalists in Kenya remains crucial.