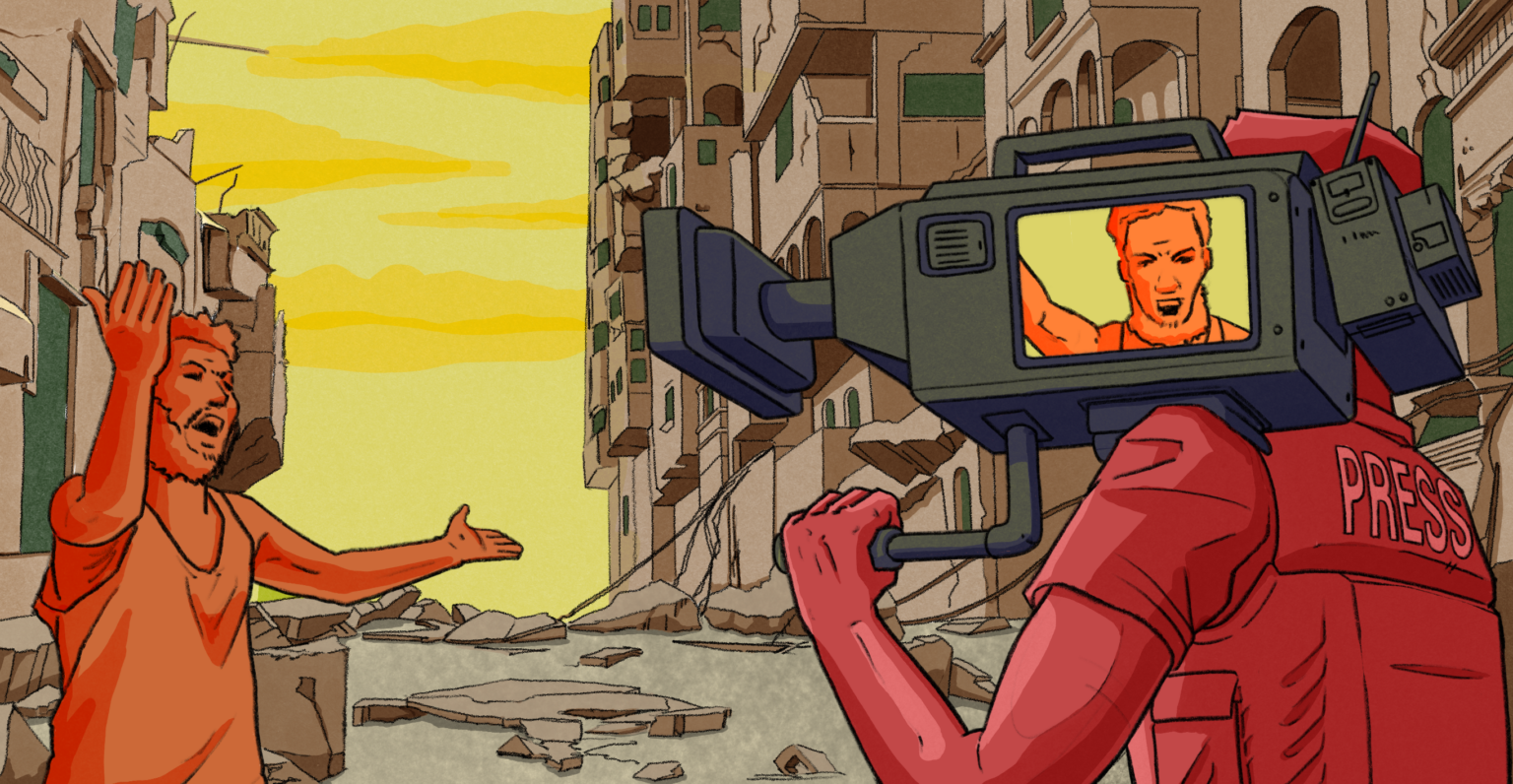

Western media’s coverage of the Gaza genocide has revealed fundamental cracks in the notion of journalistic objectivity. Mainstream outlets have frequently marginalized or discredited Palestinian perspectives, often echoing narratives that align with Israeli state interests. In stark contrast, Palestinian journalists—reporting from within a besieged landscape—have become frontline truth-tellers. Through raw, emotional storytelling, they are not only documenting atrocities but also redefining journalism as a form of resistance and a reclaiming of ethical purpose.

The duty of journalists is to tell the truth. Yet the role of mass media, according to Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s Propaganda Model, is to “amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society.”

Coverage of the genocide in Palestine is the most recent and explicit example of an inculcation campaign by the mainstream Western press. Despite restricted access to Gaza for foreign journalists prompting an open letter to the Israeli authorities in July 2024, many of the signatories wittingly conceded to tell the story through a Zionist lens. From propagating unsubstantiated claims of beheaded babies and systematic rape to self-censoring content that accentuates Palestinian suffering, they have actively discouraged an evidence-based, Palestinian-led narrative, despite the aptitude of Palestinian journalists on the ground.

BBC never fails to reference how “Hamas's attack in October 2023 killed around 1,200 people.” ... At the Times, “phrases like ‘since October 2023’ were changed and edited to ‘since the Hamas attacks’”

“It appears that the mindset of many politicians and media figures in Europe and the US is that Palestinian journalists in Gaza do not count,” writes Chris Doyle, Director of the Council for Arab-British Understanding. “They are treated as unreliable, incapable of doing a professional job.”

However, if truth is the basis of journalism, the schism between what Palestinians are showing us and what various Western outlets have curated indicates a necessary evolution of conceptions.

Such a shift would not be novel, writes Stuart Allan in Citizen Witnessing: Revisioning Journalism in Times of Crisis: “Looking across a number of national contexts, it seems fair to suggest that over the course of the last century, varied conceptions of journalism as an art, craft, trade, vocation or occupation have been gradually, albeit unevenly, displaced in favour of a proclaimed professional status, one to be differentiated at all costs from that projected onto the non-professional, inexpert citizenry.”

For the “inexpert citizenry” in Gaza, bearing witness has transformed many young Palestinians, in the absence of proclaimed professionals, into journalists. We have come to rely on many of them for daily updates, while some, like Motaz Azaiza and Bisan Owda, have been propelled to the foreground, spearheading a mode of storytelling that is deeply emotional, never neutral, but critically truthful. Through tweets and reels, reports and essays, their capacity to document the truth has not been in spite of their emotion, but in light of it.

The gravity of their reality has led them closer to the truth than any outside journalist has been able or willing to portray. As Palestinian journalist Hossam Shabat wrote, in a haunting prelude to his killing by Israeli occupation forces on March 25, 2025: “For the past 18 months, I have dedicated every moment of my life to my people. I documented the horrors in northern Gaza minute by minute, determined to show the world the truth they tried to bury.”

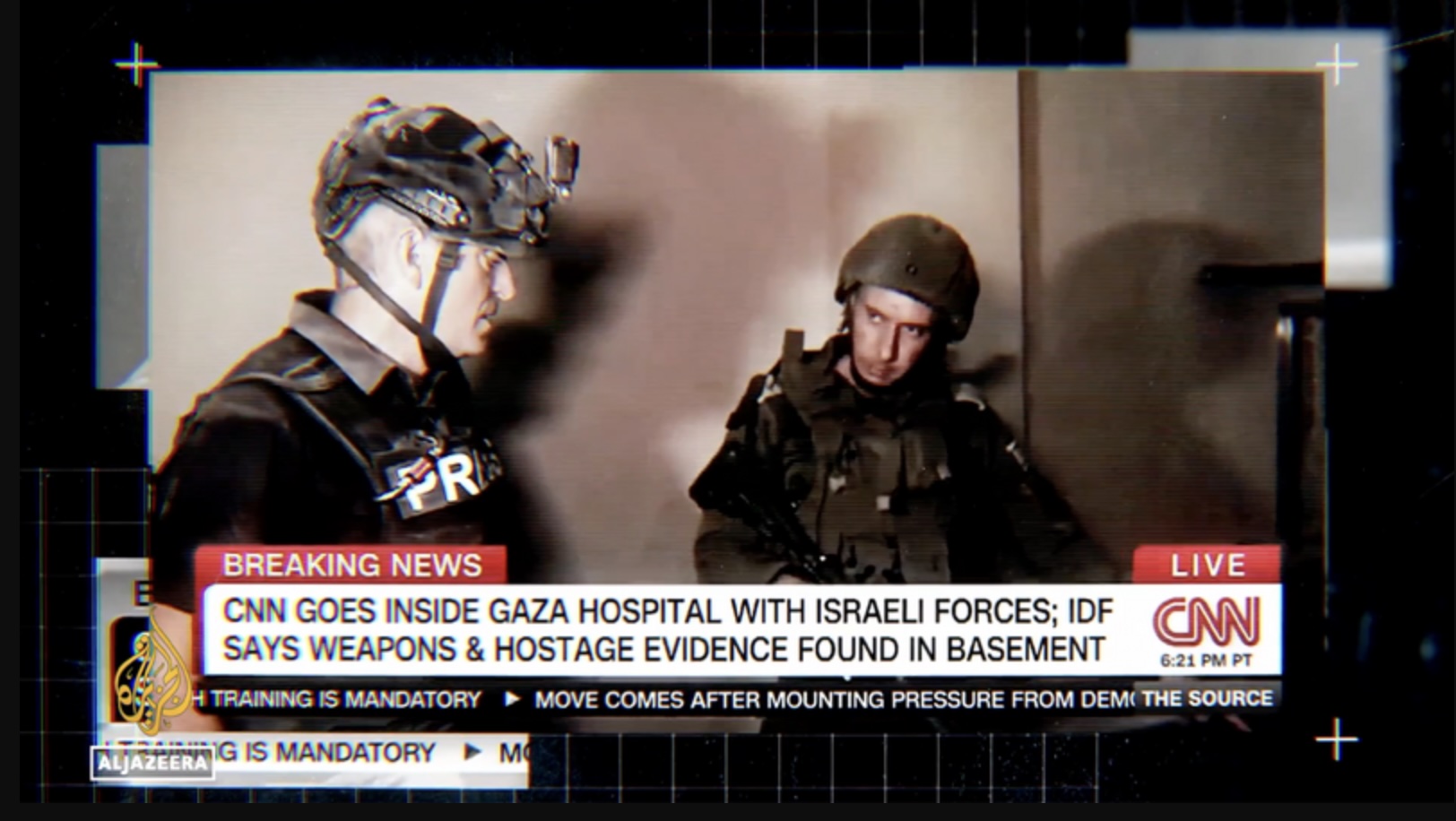

This constitutes an ongoing attempt to draw a “false moral equivalence” between Hamas’s attack and Israel’s genocide; the killing of 1,139 Israelis and the killing of 62,614 Palestinians; one day of violence and 76 years of occupation.

The Accidental Journalist: Palestinians Became Truth Tellers Amid Genocide

“Palestinian journalism has been produced under the most terrifying circumstances,” says Abubaker Abed, an accidental war reporter born on the frontlines of the genocide that has killed at least 62,614 Palestinians since October 7, 2023.

Yet “we have been let down by the international community, particularly the international media organisations,” said Abed, surrounded by fellow Palestinian journalists at a press conference in January. Despite taking the reins traditionally held by experienced correspondents, they have not been protected.

According to Article 79 of the Third Geneva Convention, “journalists engaged in dangerous professional missions in areas of armed conflict shall be considered as civilians.” This should extend “without prejudice to the right of war correspondents accredited to the armed forces,” as stipulated in Article 4. But this legal framework has not been applied and Palestinian journalists continue to pay the consequence. At least 165 journalists have been killed in Israel and Occupied Palestine since October 2023, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, making Palestine “the world’s most dangerous country for journalists.” In Gaza alone, according to other sources, that figure may be considerably higher.

To try and artificially balance things or be ‘impartial’ in the face of injustice is to be complicit. In response to that complicity, independent journalists and citizen reporters are pushing for a revisioning of the medium. By challenging the establishment narrative, investigating bias, and elevating voices in Gaza, they are spearheading a journalism in which bearing witness to genocide is a core and uncompromisable task.

“There needs to be a greater effort in the 21st century to protect journalists in conflicts, because the media war is now at such a different level” says Chris Doyle. “Controlling the narrative is so important.”

For Abubaker Abed, it is his duty to continue because the opposition in the battle for narrative control includes his occupier, world leaders, and the mainstream Western media.

“What we have been writing, what we have been reporting on, what we have been speaking, are all forms of resistance against the occupation [...] I know I am just 22 years old, but I am going to sacrifice until the last breath,” he explains. With this sense of responsibility to humanity, something largely absent from mainstream Western coverage, his dreams and aspirations as a sports journalist will always be secondary: “Even if I become a football reporter, whenever Gaza needs me I am there for it. I will quit anything and I will give up everything for my homeland. For Palestine.”

This takes Palestinian journalism beyond what journalism can ever endeavour to mean if control is the primary motivation. Palestinian journalism is journalism in its purest and gravest form, as epitomised by Hossam Shabat’s harrowing farewell, “I risked everything to report the truth.”

a lurid pretence of impartiality, the mainstream Western press set the clock on October 7. Seventeen months later, CNN continues to describe the “war on Hamas in Gaza” as a “response to the October 7 attacks.”

Challenging Objectivity in Western Media

“We must always be truthful, not neutral,” posted CNN’s Christiane Amanpour in August, 2017. “I learned from the Bosnia war never to draw false moral equivalence.”

Yet, in a lurid pretence of impartiality, the mainstream Western press set the clock on October 7. Seventeen months later, CNN continues to describe the “war on Hamas in Gaza” as a “response to the October 7 attacks.” In articles about Israel’s latest war crimes and violations of the ceasefire deal, the BBC never fails to reference how “Hamas's attack in October 2023 killed around 1,200 people.” At the Times, according to a recent Declassified UK investigation by Hamza Yusuf, “phrases like ‘since October 2023’ were changed and edited to ‘since the Hamas attacks’”

This constitutes an ongoing attempt to draw a “false moral equivalence” between Hamas’s attack and Israel’s genocide; the killing of 1,139 Israelis and the killing of 62,614 Palestinians; one day of violence and 76 years of occupation. Such a falsification of parity has led effortlessly into outright bias, not least by the British outlet infamously “committed to achieving due impartiality in all its output.” As a BBC journalist told Declassified UK: “despite the disproportionality in the conflict, programme editors would insist on ‘balancing’ Palestinian voices with Israeli ones.”

“Impartiality has failed if its key method is to constantly balance ‘both sides’ of a story as equally true. A news outlet that refuses to come to conclusions becomes a vehicle in informational warfare, where bad faith actors flood social media with unfounded claims, creating a post-truth ‘fog’. Only robust evidence-based conclusions can cut through this.”

Karishma Patel, a former BBC journalist, about her decision to resign

“What is the role of objectivity in this particular context? In the context of genocide?” asks Abubaker Abed. “What is objectivity when I see children dismembered in front of my eyes?” What is except for a justification of violence?

In a recent case of bias masquerading as objectivity, a BBC documentary titled “Gaza: How to Survive a War Zone” was removed following backlash regarding the narrator's father, a deputy agriculture minister under Hamas. The narrator himself, thirteen-year-old Abdullah al-Yazuri, spoke with Middle East Eye, describing extreme disappointment over the decision: “I have been working for over nine months on this documentary, for it to just get wiped and deleted. I found [out] about the decision to remove the documentary from the news that were revolving around the movie. And no, I did not receive any apology from [the] BBC.”

Karishma Patel, a former BBC journalist, references this in a recent article about her decision to resign. She writes: “Impartiality has failed if its key method is to constantly balance ‘both sides’ of a story as equally true. A news outlet that refuses to come to conclusions becomes a vehicle in informational warfare, where bad faith actors flood social media with unfounded claims, creating a post-truth ‘fog’. Only robust evidence-based conclusions can cut through this.”

Activism in Journalism: Lessons from Palestine

For Hamza Yusuf, a British-Palestinian journalist, “to try and artificially balance things or be ‘impartial’ in the face of injustice is to be complicit.” In response to that complicity, independent journalists and citizen reporters are pushing for a revisioning of the medium. By challenging the establishment narrative, investigating bias, and elevating voices in Gaza, they are spearheading a journalism in which bearing witness to genocide is a core and uncompromisable task.

In the face of a genocide that has been strategically disregarded by the majority of the media elite, telling stories that simply acknowledge that reality is an act of defiance.

This incorporation of activism –the policy or action of using vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change– into journalism, encourages a critical revisioning of the medium whereby the truth is not skewed and bias is not financially rewarded. “There is a need to incorporate activism within journalism,” says Yusuf, “to use that determination for a better world and your capabilities to expose and dismantle the systems that perpetuate oppression. One’s work should be driven by ethical clarity.”

Ahmed Shihab Eldin is also a journalist and an activist. He has spoken publicly about the relationship between the two practices, arguing that the two are not mutually exclusive, because “who wants to tell stories and not change anything?”

With a background at some of the world’s most prestigious mainstream news outlets, including the BBC and The New York Times, and as an Adjunct Professor at Columbia Journalism School, he is a trained and experienced journalist according to establishment standards. Yet, in the face of a genocide that has been strategically disregarded by the majority of the media elite, telling stories that simply acknowledge that reality is an act of defiance.

“You’re not a journalist, you’re an activist,” he recalls being told as he spoke on a panel in 2012 about the Arab Spring, “as if the two are mutually exclusive… Now, considering how many things I’ve been called in my life, it's really interesting to be called an activist because he intended it to be an insult but it was a compliment, something I take pride in, quite frankly. Why wouldn’t I?”

For Shihab Eldin, and other Palestinian journalists in the diaspora, the link between identity and experience is tangible. In a media culture where objectivity is heralded as the theoretical benchmark of professionalism, this may lead them to be pigeonholed, often in an attempt to discredit them, as activists without journalistic authority. However, when objectivity is a false pretence for prejudice, activism enables journalists to investigate injustice, challenge bias and reveal the truth when the establishment will not.

For journalists in Palestine, especially in Gaza, where bearing witness is a responsibility to their homeland and a necessity to galvanise international action, this link is inextricable.

In other words, says Abubaker Abed, “we are part of the event.”