Journalists have evolved from traditional tools to digital platforms, yet storytelling remains central to their work. With the rise of social media, especially among younger audiences, news organizations face challenges in delivering concise, engaging content that competes with a myriad of online distractions.

Telling stories is what we do as journalists, and it’s what we’ve been doing since we first picked up our pens and notebooks. Whether for a newspaper, a blog, a TV station, or for Snapchat, our tools may have changed from a pen and voice recorder to a camera and microphone and now to a smartphone and video editing software, but in essence: we still tell stories.

At AJ+, we target a young, digitally savvy, constantly connected millennial audience. An audience with short attention spans that consumes content through social media platforms and is continually exposed to ever-improving visually compelling content. More animations, less traditional hosted news segments. Faster, clearer, sharper content.

We continually grapple with issues journalists just a decade ago never had to think of: how to tell the news in 15 seconds? How to tell the news with no sound, since people are watching on their phones on their commute to work? How to get your audience to engage with a story about tragedy in Syria when it’s competing with a scrolling Facebook feed full of baby pictures and friends’ engagement photos? How do we get people to share the video, since shares are exponentially more valuable than likes?

These are just some of the many, many questions we ask ourselves daily. Our toolbox as digital journalists thinking mobile first, tailoring our content for our variety of platforms, and measuring our success using different metrics every other month, is full of new, shiny tools. For the purposes of this chapter, we will be discussing one of these tools: how AJ+ uses social media to engage our audience and tell better stories.

Why Social Media?

82 percent of US adults aged 18-29, our target audience, are on Facebook. People watch over 100 million hours of video on Facebook each day. It is, without a doubt, our biggest platform to date. But other platforms are gaining steam: 52 percent and 41 percent of teens in the US are on Instagram and Snapchat respectively. More than 80 million photos are shared on Instagram, and 10 billion videos are viewed on Snapchat a day. Over 75 percent of global video views on Facebook occur on mobile devices.

Cable is obsolete. Hosts are boring and long-winded. News reports are stagnant and old-school. 38 percent of households with a resident between 18 and 34 years old do not even have cable TV subscription. They stream shows, listen to podcasts, send thousands of instant messages a day. Social media is the environment they are constantly surrounded by; it is where they are. It is fully a part of our lives today, seamlessly integrating into our stream of consciousness.

The competition for eyeballs is fiercer than it ever was. News is competing with brands, advertisers, politicians – all willing to shell out to capture a slice of an ever-decreasing attention span.

It is a natural evolution for news to begin to integrate social media into their reporting on news. One of the earliest adopters was The Stream – a pioneering show by Al Jazeera that integrated tweets and Skype calls into their daily show. Several years later, however, the reality is that a daily one-hour show that isn’t even available online is both too cumbersome and too long for today’s audience.

The 30-year-old that used to sit through a two-hour documentary can no longer sit through a 30-minute show, let alone the 18-year-old who taps through their friend’s Snapchat story because the 10 second maximum for a photo or video feels too long.

News breaks on social media before traditional news every single time. The live-tweeting and live-streaming my colleagues and I utilised during the Egyptian revolution has gotten smarter and savvier. Tools to timestamp, geographically verify, and vet people who tweet are aplenty, from Storyful to Dataminr to SAMDesk.

Faster internet connections and convenient live-streaming that send push notifications to your twitter followers through Periscope couldn’t be easier. While on the Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia in 2015, with a touch of a button I was live-streaming to the entire world the aftermath of the stampede that killed hundreds of people. I recorded interviews with survivors using nothing more than my iPhone, sent the interviews via WhatsApp and Slack to my colleagues, and the story was up before you could blink.

Time is of the essence. Being first to the story is no longer about having the story at the top of the hour, or even the minute. Today, it is about seconds. The news that is picked up, retweeted, re-shared, and exponentially amplified, is the news by the person who got there first.

But AJ+ is not a traditional newsroom. Most of the time, we do not have our own staff on the ground around the world to report for us. We use content curated online, by other eyewitnesses.

This gives us thousands of journalists and unhindered access to as many corners of the world as our keyboards can reach, but the same questions of citizen journalism and user-generated content remain as valid today as they did a decade ago: how do we verify the footage, images, audio? How do you know the framing of the footage? The agenda of the shooter? The context and nuance behind? Is it fair to use this footage without permission? What if we reach out and they don’t answer us in time? Do we pay later? Do we have a fair use argument?

In this chapter, we will highlight some case studies of how we use social media – the home runs, and some flops. We will discuss how social media content sourcing helps us tell better stories, and briefly touch upon how we use social media platforms to drive traffic as well.

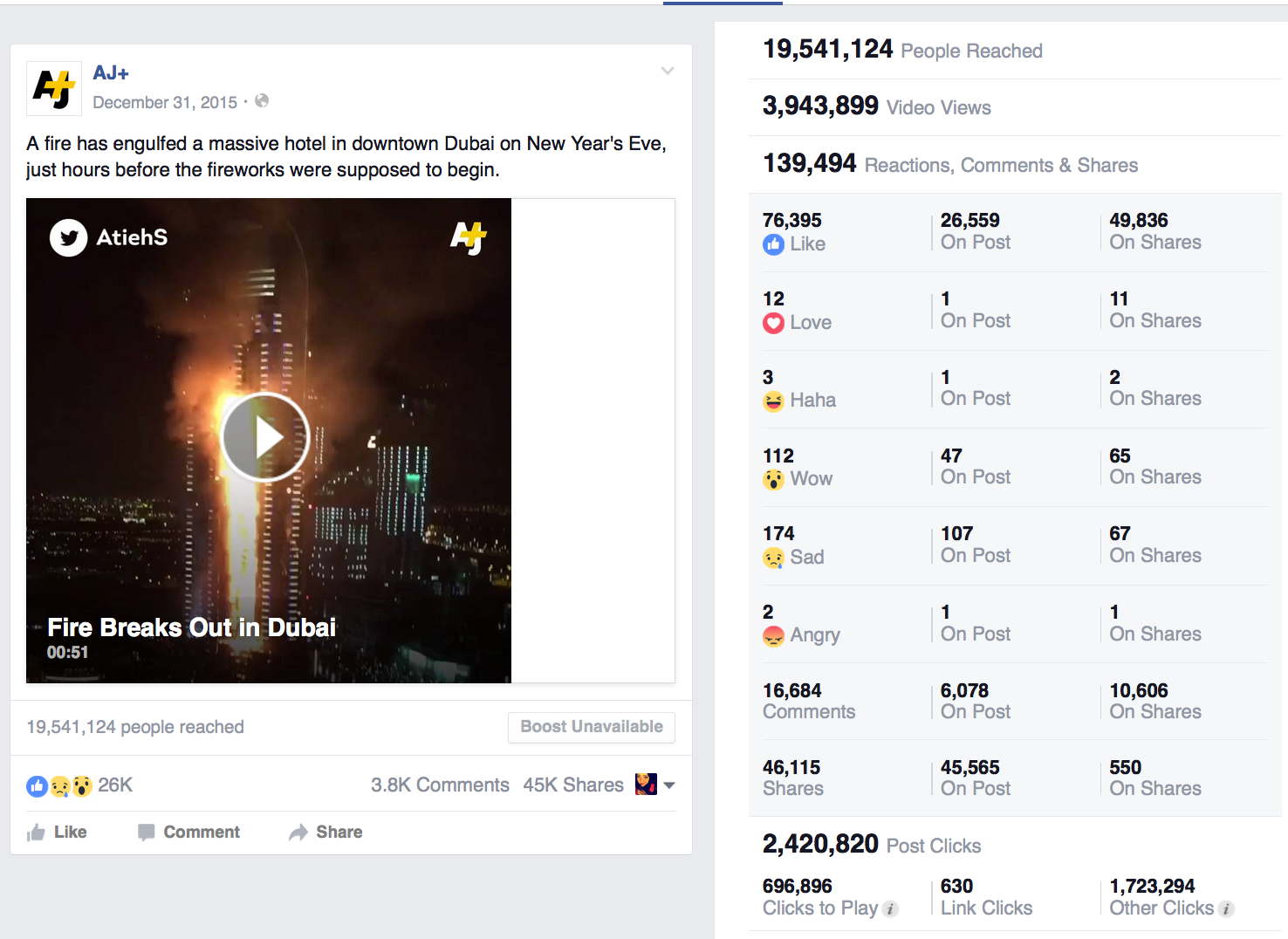

New Year’s Eve in Dubai

On New Year’s Eve 2015/16, a massive fire broke out in Dubai at the iconic Address Hotel. Being on the West Coast of the United States rarely plays to our advantage in terms of our time zone, but in this case, it did. The fire started soon after 10pm Dubai time, which was early afternoon at the AJ+ headquarters in San Francisco. As with many stories, it broke on Twitter. At AJ+, we are subscribed to a service called Dataminr, which uses geotagging to attempt to verify tweets.

Before the news broke on traditional media, at least 15 minutes before I got a push-notification from the BBC saying there was a fire, I had the news. I had tracked down two Twitter accounts of people posting videos from opposite sides of the building from different views, as well as three people who were using Periscope to livestream the event – one from the base of the hotel at a restaurant, one from a high-rise across from the hotel, and another from a high-rise across the city - with a view of the entirety of the hotel. The footage was immediate, visceral, and powerful since it was not recorded by a steadfast journalist but a panicking viewer (“Oh God, it’s burning! How will they get the people out?").

For this footage, verification was easy: the footage was live-streaming, the Address Hotel is easily identifiable, it had never been on fire before, and the people live-streaming were discussing the date, the fireworks, identifying where they were and what they were seeing. The tweets were posted just minutes ago, and were appearing by the dozens every minute. I had more than enough content to create an AJ+ story.

[Pro tip: when searching for eyewitnesses on the scene who are live-tweeting/ streaming, use the keywords “I” “I’m” “my.” Deutsche Welle has a list of tips for finding breaking news. Searching for keywords and swear words (in the language of the country the incident is happening in) are also good tricks.]

But the footage did not belong to us, and we did not have permission to use it. The majority of the footage uploaders weren’t answering the dozens of media asking for permission to use their footage. One did. Time is of the essence. Tick Tock.

Fair use and fair dealing is a long, complicated topic that varies from country to country. For the sake of convenience, let me summarise by saying that, as a news organisation headquartered in the United States, I felt we had a compelling argument to use the UGC without permission. Our story was transformative for the following reasons: we did get permission for some of the content (one eyewitness even sent me footage via WhatsApp that wasn’t published anywhere else); the people posting were recording for the world to see; we did not use any one source and as such were not simply ripping their content; we added tweets (which are typically in the public domain, AJ+’s version of vox pops), and included a statement by the Dubai police posted on social media, and included a short script detailing what was happening.

Today, if you wait for the wires, you will be hours late to the story. On New Year’s Eve, I was the only producer working. Within an hour of seeing the first tweet pop on my radar, I had published the story. Text on screen, music, cuts, transitions, texts, subtitles.

There is a sweet spot with a story like this: people hearing there’s a fire, a curiosity gap to see the shot of fire and provoke emotional arousal, to know what’s going on, to gawk, but not necessarily to tune in to a 20-minute shaky periscope.

And for our target audience, who not only are not watching or even own televisions, but will most probably not have channels in the Middle East who would have the news first, this is a prime kind of story. It is a story that is in no way polarising and so not shareable, is timely, is different than traditional news reports, and as such: a success.

The video had over 3 million views within the day. And more importantly: over 40,000 shares. At the time of writing this, it had a reach of 20 million people.

Female Suicide Bomber

The terrible events in Paris in November 2015 were of worldwide importance. Over several days, we produced a number of stories as developments occurred. A couple of days after, news of a female suicide bomber who blew herself in a police raid on November 18 as police circled her building broke during our production day.

AP had footage of the attack – and in it, they identified the woman Hasna Ait Boulahcen. There were, however, no photographs of her.

The internet and social media had started circulating images of her. Using these images, we felt fell under fair use since they were adding value to the story. However, our major problem here was verification – regrettably, we did not take the time to track down where the images came from. Our mistake was assuming that other news outlets who ran with the images had verified them, which was, of course, not the case. We were equally as liable as the first news outlet who bought pictures that were not given freely, and ran with them as fact.

In fact, the photos were of a Moroccan woman, Nabila Bakkatha, who lives in Morocco. We corrected the error by working together with Al Jazeera Arabic, who had tracked her down, and running an interview with her explaining her side of the story. Our follow-up correction story did extremely well – we admitted to our error, had original footage, and had her tell her story of how the internet made her a victim of mistaken identity.

Palestine

Between UGC and highly produced stories by our video journalists, we have a version of reporting that combines old-school journalism with social media to curate and report in bursts of soundbites, images, information and live-reporting. When we deployed a team to report on the ground in Palestine, they filmed for longer highly informative pieces that told a larger story, which were edited in our offices, such as one on the separation wall, for example. But that’s not all they did.

One of the things that works best for AJ+ is raw-like videos. People like the snapshots, and not the highly produced pieces. The rawness gives immediacy, closeness to the moment. They tell the human stories. Even though shooting on mobile produces shaky footage that is nowhere near the quality of cameras in audio or video, delivery is almost immediate, and the story is the same. The difference is speed.

In Palestine, our producer and host would upload Instagram photos of children playing football. They would record soundbites from young men who were throwing rocks using their phone. These pieces connected with our audience. They live-streamed, filmed and edited on their phones and tweeted photos and video as news broke.

Unlike agency footage, which is still filmed according to high broadcast standards – wide shots, VOX pops with people looking straight into the camera, cut away shots and so on, footage produced for AJ+ is much closer to citizen journalism, with the professionalism, rather than the polish of agency footage. When we produce, we think social media and app-first, and think of the consumption patterns of each distribution platform.

Footage on the ground by citizen journalists is much more powerful, much more first person. The shakiness of it, the words spoken, the rawness, all contributes to creating more powerful footage. The biggest benefit to us being on the ground and not relying solely on UGC is clearly verification. But for our online audience, social media meant producers could live-tweet powerful quotes, snap images, even quickly interview and stream a sound bite. Mobile reporting teams are the future of breaking news. Our coverage in Palestine increased our audience by thousands. And then we replicated it following refugees across borders in Europe – which won us a Webby award.

As AJ+ producer Shadi Rahimi put it:

“Mobile reporting offers the opportunity to engage directly with the social media audience – i.e. our target millennial viewership – unfiltered and in real-time. The reason much of our […] content went viral had to do with these main factors: 1) Relevance; 2) Timing (immediate delivery on social platforms); 3) Conforming to social norms/standards (the sharing audience members raised their social profile by associating themselves with the content first); 4) Raw emotive video. […] Social media audience appreciates raw video, despite the quality, because there’s a layer of trust built when there’s no editing”.

The rawness, as we said, is a key part of our success. We search for emotive moments that provoke reaction: positive, happy, negative or angry. People share content that provokes reaction. And our millennial social media audience is a generation of media consumers that trusts the raw over the polished.

Cover It Live: Periscope, Snapchat, Facebook Live, Instagram

When we began piloting for AJ+ in 2013, many emerging platforms such as Periscope and Facebook Live did not exist, even though live-streaming did. In our early days, we used Stringwire to livestream, which was routed to our YouTube channel but was choppy and unreliable. Periscope was smoother: it changed the media landscape, as have its push notifications to our Twitter followers. As the tools to better engage our audience grow, so do we.

During the height of the 2015 refugee crisis in Europe, we deployed a presenter, producer and shooter to follow refugees. We used a multiplatform approach in an unprecedented way. It was our first foray into Facebook Live, and this experiment did exceptionally well. Considerations of time zones was taken into account when deciding when to go live – research shows engagement is a lot higher when people tune in while we are live rather than watching later.

Unlike television, which relies on a presenter detailing the news, our streaming was much closer to citizen journalism – literally walking with refugees, talking to them, showcasing children. We told the human stories and were a forum for live conversation between refugees and viewers – allowing our audience to engage by asking questions of the refugees relayed by the presenters. Just as with Ferguson and Baltimore in the United States, we believe that communicating directly with the social media audience is what works now.

Our stories go beyond the reports we create – the behind the scenes on several platforms has done very well. For example, the producer in Palestine took over our Instagram account, sharing short stories as captions of photos. A presenter in New Hampshire took over our Snapchat channel, live-snapping Bernie Sanders on stage during a campaign event for the Democratic nomination for the presidency of the United States.

As an entity that does not have our own bureaus, we often rely on local video journalists on the ground to cover events of interest to our audience – in the United States this has been from Black Lives Matter Protests on university campuses to the takeover of a federal building in Oregon by armed anti-goverment protesters.

They take over our Periscope feed, and though hearts are the easier way to measure engagement, the metrics we use are in development. The video journalist records short interviews on their phone, and sends it to us via a Slack channel we have created. Although this technically is not UGC, the way we record, share and distribute this content is very familiar to our target audience’s way of consuming social media.

Looking Forward

By the time this gets published, and by the time you read it, AJ+ will be experimenting with even more emerging platforms. Facebook Live has become a game changer. Virtual Reality, 360-degree video are tools we have started to experiment with, and we are learning about.

From the birth of AJ+ to today has been a rollercoaster, and one in which AJ+ has learned so much. We’re clearly on the right track: on Facebook for example, our engagement scores are through the roof. We average half a million interactions every single day, and a reach of 30-40 million people per day – all organic, nothing paid. We’re growing, and we’re expanding.

But six months from today, a year, we can’t look like we do now. We were lucky to be innovators in this field, but a lot of competitors are now snapping at our heels. If we aren’t changing and adapting and experimenting and innovating, we won’t grow.

As any organisation at the forefront of digital storytelling experience, we have to constantly stop and remember that the industry is shifting rapidly. Existing on social media platforms, we are at the mercy of their algorithms.

Social media is our bedrock – but we know that there are only so many Tweets people will see before they get bored. GIFs are something we are experimenting with. Should we be including different kind of content? Images? Memes? More infographics? Medium posts? Partnerships? Should content be more tailored for each platform? Should we hire an emoji expert for Snapchat?

We’re experimenting with comedy and skits. Targeting a younger audience. Should we crowdsource information from our audience?

Every day, new questions and issues come up. And every day, we have to tackle them head on. But one thing is clear: AJ+ has its finger on the pulse of the internet, the language of our audience. We understand our audience, we are our audience, and we have found our niche. We make people laugh, we make people cry. Our content empowers, engages, and informs.

References:

Facebook Business (2016, February 10). Capture Attention with Updated Features for Video Ads. Facebook. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/business/news/Features-for-Video-Ads-UK

Facebook Business (2016, February 10). Capture Attention with Updated Features for Video Ads. Facebook. Retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/business/news/Features-for-Video-Ads-UK

Instagram News (2015, September 22). Celebrating a Community of 400 Million. Instagram. Retrieved from: http://blog.instagram.com/post/129662501137/150922-400million

Firer, Sarah (2016, April 28). Snapchat User `Stories' Fuel 10 Billion Daily Video Views. Bloomberg. Retrieved from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-28/snapchat-user-content-fuels-jump-to-10-billion-daily-video-views

Dredge, Stuart (2015, April 23). Facebook 'excited' about ads potential as it reaches 4bn daily video views. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/apr/23/facebook-4bn-daily-video-views-ads.

Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (2016, July 13). One-Quarter of US Households Live Without Cable, Satellite TV Reception – New GfK Study. GfK. Retrieved from: http://www.gfk.com/en-us/insights/press-release/one-quarter-of-us-households-live-without-cable-satellite-tv-reception-new-gfk-study/

Julia Bayer and Ruben Bouwmeester (2016, February 19). How to find breaking news on Twitter. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved from: http://www.dw.com/en/how-to-find-breaking-news-on-twitter/a-19061495

Rahimi, Shadi (2015, May 1). How AJ+ reported from Baltimore using only mobile phones. Poynter. Retrieved from: http://www.poynter.org/2015/how-aj-reported-from-baltimore-using-only-mobile-phones/341117/