Both countries have a disgraceful history of disregard for the rights of media staff who are the victims of violence, particularly in conflict zones

The decades-long struggle against impunity in the targeting and killing of media staff has made significant progress in recent years. High-flown rhetoric from political leaders has been converted into a United Nations Action Plan on the Safety of Journalists and the launch of an International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists on November 2.

But the world remains a hostile place for journalism. The latest UNESCO Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity shows that reporters are still victims of a continuing spiral of targeted violence.

According to the United Nations, of the 117 journalists killed for doing their job in 2020-2021, almost 80 per cent were killed while off duty in targeted attacks at home, in their vehicles or in the street. Some were killed in front of family members, including their children.

That’s why justice for journalists who are the victims of violence is not just about creating a safe working environment, it is also about holding to account the powerful people and institutions who order these attacks and carry them out.

However, too often the strategic, political and commercial interests of governments - even the most democratic of them - still get in the way of delivering basic justice.

Over the past month, for example, the United States and Israel, have been at the centre of two diplomatic rows involving pivotal cases concerning the denial of justice in the killing of journalists.

On November 18, President Joe Biden ruled that Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman will be granted immunity in a US lawsuit over the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the distinguished writer and Saudi dissident who was brutally killed and dismembered in October 2018 by Saudi agents in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

The US has sacrificed justice for Jamal Khashoggi to maintain friendly relations with Saudi Arabia

At the time, the US intelligence services suggested the operation was ordered by Prince Mohammed, and Joe Biden, then campaigning for election, criticised him over the killing.

But times and political conditions have changed, to the extent that Washington is willing to allow the Prince to dodge a court action brought by Khashoggi’s fiancée, Hatice Cengiz, and the rights group he founded, Democracy for the Arab World Now.

One reason, as set out by Justice Department attorneys in a document filed in US District Court for the District of Columbia, is that "the doctrine of head of state immunity is well established in customary international law".

Well up to a point. According to academic research in the 20 years since 1990, some 65 heads of state have been prosecuted, many of them for human rights abuses and breaches of international humanitarian law.

In most cases, and in the absence of robust international legal instruments, bringing government leaders to book is a challenge given the political climate and the overwhelming priority given to defence of national self-interest.

Although a US judge will ultimately rule on the question of immunity in the case of Prince Mohammed, journalism support groups and activists are rightly angry that the US has sacrificed justice for Khashoggi to maintain friendly relations with Saudi Arabia.

Biden had already indicated where his political sympathies lie when he famously fist-bumped the Crown Prince in July on a visit to Saudi Arabia to discuss energy and security issues. It may have been inevitable, therefore, that his focus on maintaining America’s longstanding alliance with Saudi Arabia would take precedence over human rights and justice, even for a courageous and notable journalist.

Meanwhile, a few days earlier another American ally, Israel, also trashed the notion of justice for journalism and press freedom when it dismissed plans for American investigators from the FBI to look into the controversial killing of Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh who was shot dead by the Israeli army in May this year.

During the Iraq war, the US steadfastly refused to allow external investigation of incidents involving its soldiers where media staff were killed or injured

Shireen, one of the Arab world’s best-known journalists, who had covered the conflict for decades, was shot on May 11 while covering a military raid in the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank for Al Jazeera.

She was wearing equipment and body armour that was clearly marked “press”. What followed were multiple investigations by leading media, rights groups and international organisations which concluded that the veteran reporter was killed by an Israel soldier. Eyewitness testimony suggested it was a targeted strike.

Israel’s initial response was that she might have been killed by Palestinians, or she died in the crossfire of a firefight. Only after intense global protests by media and human rights groups did they carry out their own internal investigation. This found that although she had probably been killed by the Israeli Defence Force, it was an accident. No further action would be taken, and the case closed.

However, Shireen’s family, backed by her employer Al Jazeera, continued to press for the United States for more action and after months of pressure, supported by members of many members of Congress, the FBI agreed to take up the case.

Israel immediately denounced the move. The FBI investigation, according to Defence Minister Benny Gantz, was nothing more than “interference in Israel’s internal affairs”. He said Israel "will not cooperate with any external investigation”.

In truth, few people with experience of investigating cases of impunity involving journalists over the years are surprised. Both Israel and the United States have a history of neglect and disregard for the rights of media staff who are the victims of violence, particularly in conflict zones.

During the Iraq war, for example, the US steadfastly refused to allow external investigation of incidents involving its soldiers where media staff were killed or injured.

Israel has been equally dismissive of appeals to allow independent investigation of numerous incidents of attacks on Palestinian media and journalists by its armed forces

A particularly notorious example was a tank assault on journalists staying at the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad in 2003. Three journalists were killed, and others wounded. The US refused to co-operate with any external investigation although evidence later emerged from within the US military of a targeted attack and a Spanish judge named and indicted three US soldiers, he said were responsible.

And Israel has been equally dismissive of appeals to allow independent investigation of numerous incidents of attacks on Palestinian media and journalists by its armed forces. Where inquiries have taken place, they have been internal and usually self-serving in their conclusions.

One notable example, also in 2003, was the killing of American human rights activist Rachel Corrie who was crushed by an Israel army bulldozer. That led to an internal investigation and, as in the recent case of Shireen Abu Akleh, a finding that the death was accidental with no further action taken.

For the time being, the denial by Israel of the right of American law enforcement officers to investigate the killing of an American citizen abroad may complicate relations with Israel but it reinforces claims of an Israeli cover-up of Shireen’s death.

But this case, like so many that precede it, illustrates that for any campaign against impunity over violence against journalists to succeed, it will first have to ensure that governments are open to independent scrutiny, that they respect the rights of news media and, most of all, that they live up to their self-image as standard bearers of democracy and human rights.

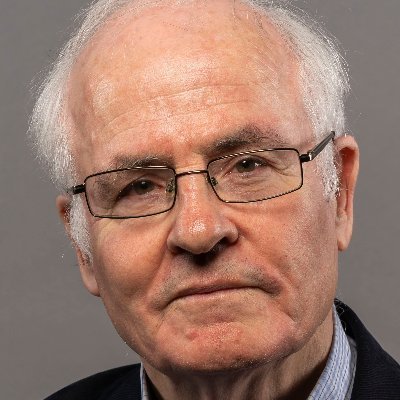

Aidan White is President of the Ethical Journalism Network and former General Secretary of the International Federation of Journalists

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera Journalism Review’s editorial stance

![Palestinian journalists attempt to connect to the internet using their phones in Rafah on the southern Gaza Strip. [Said Khatib/AFP]](/sites/default/files/ajr/2025/34962UB-highres-1705225575%20Large.jpeg)